Despite decades of deinstitutionalization and the best efforts of community mental health services, individuals with psychiatric disabilities living outside the hospital may be described as in the community, but not of it. They may live in neighborhoods alongside people without disabilities. Their residences may resemble those of their neighbors. Yet many people who are psychiatrically disabled lack socially valued activity, adequate income, personal relationships, recognition and respect from others, and a political voice. They remain, in a very real sense, socially excluded.

Previous conceptual work

Previous efforts in psychiatry to conceptualize social integration, while constructive, have incompletely captured its social dimensions, instead overemphasizing location and functioning as indicators. Reflecting the goals of deinstitutionalization, location has referred principally to residence outside the psychiatric hospital. "Amount of time spent in the community" is one well-known, location-focused definition (

6 ). Functioning refers, in contrast, to the ability to sustain oneself outside the hospital. Functioning includes use of everyday goods and services and fulfillment of social roles. An example of a functioning-oriented definition is "making independent purchases and money management" (

6 ).

Social dimensions of disability have in fact been the subjects of vigorous debate, but largely outside psychiatry. Social role valorization theory, originating in the study of developmental disabilities, pinpoints ways in which people with disabilities have been devalued by society, and it advocates, in response, greater access to valued social roles. Social role valorization theory is principally concerned with improving the experience of individuals who are disabled (

7,

8,

9 ). The social model of disability, in contrast, emphasizes analysis of society. Grounded in the social sciences, this way of thinking locates disability not in the individual but in the barriers to individual accomplishment that disabling social structures, policies, and practices present (

10,

11,

12,

13 ). Social change, rather than valued roles, is what social model analysis calls for.

Proponents of the social role valorization theory and social model positions have historically been at odds. However, efforts to bring the two together are beginning to appear (

14 ). Both the debate and the social model perspective have, up to now, remained external to thinking about social integration and psychiatric disability, however. Only social role valorization theory appears to be referenced in the mental health services research literature (

15 ).

The capabilities approach as a conceptual framework

The capabilities approach to human development provides the conceptual framework for the research reported here. Grounded in development economics and moral philosophy, the capabilities approach is a way of organizing thinking, research, and measurement to more dynamically represent quality of life. Until recently the capabilities approach has been applied chiefly to the study of standards of living for disadvantaged populations living in developing countries (

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21 ). Now, increasingly, it is being put to other uses, including the rethinking of disability and disparities in health (

22,

23,

24,

25 ).

Conceived as an alternative to paradigms emphasizing satisfaction and income as quality-of-life indicators, the capabilities framework takes as its measure of quality degree of human agency—what people can actually do and be in everyday life. What people can do and be is in turn contingent on having competencies and opportunities. Opportunities are provided by social environments. To ensure capability, social circumstances must offer opportunities for individual competency to be developed and exercised. To define social integration, we borrow from the capabilities approach its emphasis on agency, its developmental perspective, its recognition that individual development is contingent on supportive social environments, and its core concepts of competency and opportunity in delineating the process through which social integration develops.

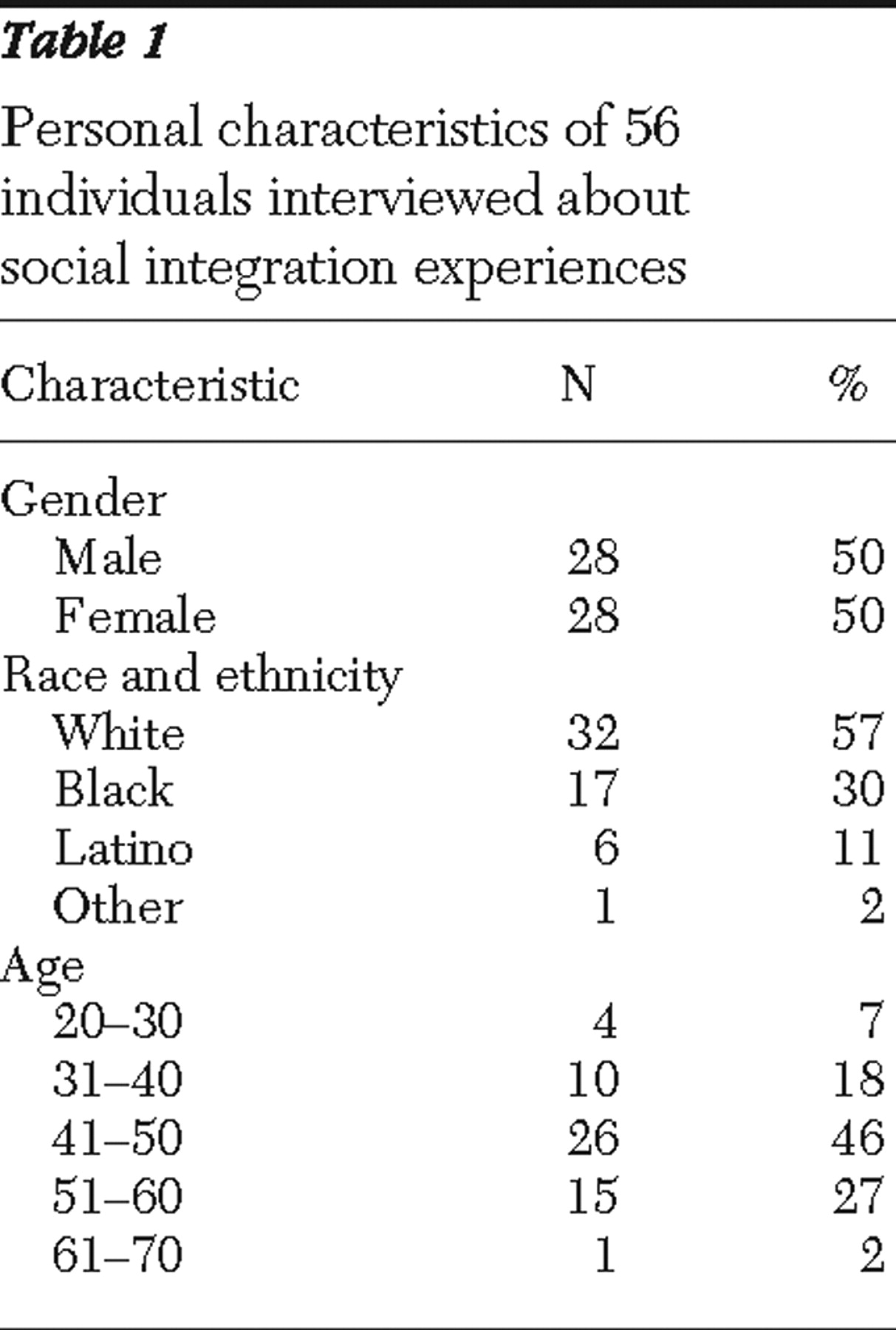

This article results from an anthropologically informed, qualitative study that aimed to define social integration in the context of psychiatric disability, construct a conceptual model depicting social integration processes, and develop an empirically derived theory that explains how social integration takes place. This article addresses the first aim: providing the definition.

Results

On the basis of this analysis, we have defined social integration as a process, unfolding over time, through which individuals who have been psychiatrically disabled increasingly develop and exercise their capacities for connectedness and citizenship.

By connectedness, we mean the construction and successful maintenance of reciprocal interpersonal relationships. These relationships provide not only companionship and good feeling but also access to resources. They include persons without psychiatric disabilities who are outside the mental health system as well as those with disabilities. Interpersonal connectedness, as we envision it, extends well beyond receipt of social support.

Social, moral, and emotional competencies are required to sustain interpersonal connectedness. Social competencies refer here to effective communication—the ability to articulate thoughts and feelings in ways that engage others and make oneself understood. Moral competencies are the basis of trust—for example, accountability, reliability, credibility, and honesty. Empathy and a capacity for commitment are examples of emotional competencies for connectedness.

Social currency is also essential to connectedness. Social currency is that stock of personal attributes that sparks others' interests in connecting. Knowledge, talents, interpersonal style (for example, warmth, humor, and genuineness), and physical characteristics (attractiveness, for example) are forms of social currency. Social currency and competencies for connectedness are impaired by experiences associated with severe mental illness and psychiatric disability.

Connectedness also means identifying with a larger group. Connectedness in this sense is subjective—the feeling of being part of a whole. Identification is based on the perception of "having things in common with" others and leads to the sense that one has a stake in (is personally affected by) what happens in and to the group. Part of what social integration means for persons who have been psychiatrically disabled is increasing identification with groups not defined by mental illness.

Citizenship refers to the rights and privileges enjoyed by members of a democratic society and to the responsibilities these rights engender. The rights of U.S. citizens are protected by the Constitution (for example, basic civil rights) and by statute. Our responsibilities are to obey the law, participate in public discourse and decision-making processes, and contribute to the common good. Historically, the rights of persons with psychotic illness have been restricted on the grounds of mental incompetence, reducing them to second-class citizens or citizens of programs serving "special populations" (

30 ). On the same grounds, they have been exempted from social and personal responsibility. Our definition of social integration calls for full rights and responsibilities of citizenship. By including the idea of citizenship, we acknowledge social integration's political dimension.

Discussion

Several attributes of this definition should be made explicit. First, it posits growth and development, rather than stabilization, as the object of psychiatric treatment for persons disabled by mental illness. Flourishing, not simply functioning, is the envisioned outcome. Second, this formulation casts persons with psychiatric disabilities as agents rather than—to invoke a current construction—"consumers." Third, the definition overlaps with conceptualizations of recovery from mental illness that depict social exclusion as at least part of what is being recovered from and acknowledge the social character of the recovery process (

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36 ). The considerable variability in how recovery is defined underscores the value of clearly delineating the relationship between the two concepts.

The idea that meaning has a rightful role to play in thinking about outcomes of mental health treatment is also reintroduced in the definition. In recent years, psychiatry has largely ignored the fact that "making meaning" can be as important as controlling symptoms in treating persons with severe mental illness. To "make meaning" is to learn to interpret or reinterpret one's experience, to find a reason for living, or to succeed in living a worthy life. One way of staking a claim to worthiness is by making the social contributions of citizenship.

This is personal meaning-making. Definitions also make meaning for analysts working to understand social problems—and from those understandings, craft solutions (

37 ). To define a social problem is not simply to specify a particular segment of reality; it is a choice with implications. For example, if we define homelessness as chiefly a problem of "housing readiness" for people living on the streets or in shelters, then corrective measures will be devoted to repairing the deficits of individuals. If, alternatively, we define it as an insufficient supply of residential options, then remedies will target specific resource scarcities. The two definitions trace the origins of the problem to different sources—people versus housing—with differing implications for policy (

38 ). Similarly, recovery from mental illness can be construed as the disappearance of symptoms, as living well with symptoms, or as social integration. The definition chosen determines "what counts" as recovery-oriented policies and services.

Rethinking social integration from a capabilities perspective means considering not only individual quality of life but also required social change. Required social changes are of at least two types: the reduction of societal barriers to integration and the creation of opportunities for social participation. Reduction of barriers can be accomplished by refining accommodations presently available to persons with psychiatric disabilities and by reworking social structures—for example, the Social Security insurance system that creates disincentives for beneficiaries wishing to end dependence on entitlements and support themselves through earned income. A test to demonstrate the effects of eliminating Social Security disincentives (in conjunction with work and treatment supports) on employment outcomes for persons with schizophrenia and affective disorders is, in fact, under way (Frey W, Drake R, Goldman H, et al., unpublished manuscript).

Opportunities for social integration include those aimed at developing competencies and those that allow competencies to be exercised. Providing opportunities for competency development lies within the scope of mental health services; creating opportunities for exercising competencies falls to the larger society.

Competencies for social integration differ from those targeted by rehabilitation efforts in that they address obstacles to inclusion rather than illness-related impairments. Literacy—competence in reading, writing, and the use of computers—is an example of an integration-oriented competency. Education for literacy is one form that services aimed at developing competencies for integration might take. The literacy example also highlights the value of cross-sector collaborations in creating opportunities for competency development. Some requisite general characteristics of such opportunities include assumption of competence or potential competence on the part of persons served, emphasis on socially valued activities, an "action first" approach (as in supported employment's "place-train" rather than "train-place" approach), and a tolerance for risk.

What are other service implications of a capabilities approach to social integration? The emphasis on agency invites a reexamination of the ideas underlying existing clinical and service paradigms. History teaches us that what may appear at one point in time to be "truths" about the limited capacities of population subgroups—women or African Americans in the United States, for example—may later be revealed to be unfounded assumptions. The "truth" about the inevitably chronic course of schizophrenia is already being recast in a similar way (

39,

40,

41,

42,

43 ). What if other aspects of the meaning of mental illness were subjected to similar scrutiny?

The meaning of social integration is not different for different people. Accordingly, our definition applies to persons with and without psychiatric disabilities and represents an ideal. Connectedness and citizenship as depicted here are ends to which we all, to varying degrees, aspire but never completely achieve. Different experiences place people at different distances from these ends. Individuals socially marginalized through psychiatric disability find themselves relatively far removed from the integration ideal.

In developing this definition, we have borrowed not only from the capabilities perspective but also from contemporary writings in psychiatry. For example, social integration figures explicitly in a comprehensive approach to treating psychotic illness developed by Apollon and colleagues (

44,

45 ), where it has two different meanings. A set of interpersonal relationships—"connectedness" in this study—is the first. The second refers to a moral position in which the individual accepts responsibility for the way the world is and through a unique "social project" makes an effort to change it for the better (

46 ; Apollon W, ethnographic interview, 2005). This moral position links the individual to the larger society and informs our use of the idea of citizenship.

In planning research on social integration, the initial inclination is perhaps to think of it as an outcome. However, the definition offered here is deliberately process oriented. By emphasizing process, we call attention to the importance of understanding not just what predicts social integration but how it happens. An understanding of process will likely contribute most directly to efforts by mental health services to enhance social integration for persons with psychiatric disabilities.

One immediate use we might make of this definition and the capabilities framework that informs it is to begin to formulate ensuing research questions. We propose the following examples, which, although far reaching, can be made operational in various ways once they are clearly stated. Mental health services researchers might reasonably ask, for instance, what competencies for connectedness and citizenship persons with psychiatric disabilities presently possess? What opportunities are available to them? An investigation stemming from such questions would stand in stark contrast to inquiries eliciting, for example, consumer satisfaction and preferences. It lays the foundation to ask what opportunities for developing competencies for social integration should look like. Model development is another clear next step in this conceptual project and is needed to guide empirical investigations.

Models help us to organize indeterminate realities and develop valid measures of connectedness and citizenship. For guidance in measure development, we may also look to social science. Social network methods provide good starting points for thinking about the assessment of connectedness. These methods have a distinguished history in social science and in health research (

47 ), one that includes studies of persons with severe mental illness (

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58 ). Studies of civic traditions of participation (

59,

60 ), public deliberation (

61,

62 ), and conditions of citizen engagement more generally (

63 ) promise to inform the development of measures of citizenship.