Aside from the family, the school environment is perhaps the most important context in which the developmental process takes place. Early intervention in primary schools is essential to help children learn to cope with emotional problems and make nonviolent choices. Thus it is important to predict schools' potential needs for such interventions.

This report is based on a national survey of 11,283 fifth-graders in 2,390 schools from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study-Kindergarten in 2003–2004. The report describes associations between teacher-reported externalizing and internalizing behavior problems of children and key school sociodemographic features. Because the initial sampling did not include children who were not in kindergarten to be followed up, the sample we used in this study represents approximately 83% of all fifth-graders nationwide. The externalizing scale includes six behaviors: argues, fights, gets angry, acts impulsively, disturbs ongoing activities, and talks during quiet study time. The internalizing scale includes anxiety, loneliness, low self-esteem, and sadness. We created dichotomous measures for each scale; children at or above the 95 percentile on each scale were classified as having substantial problems.

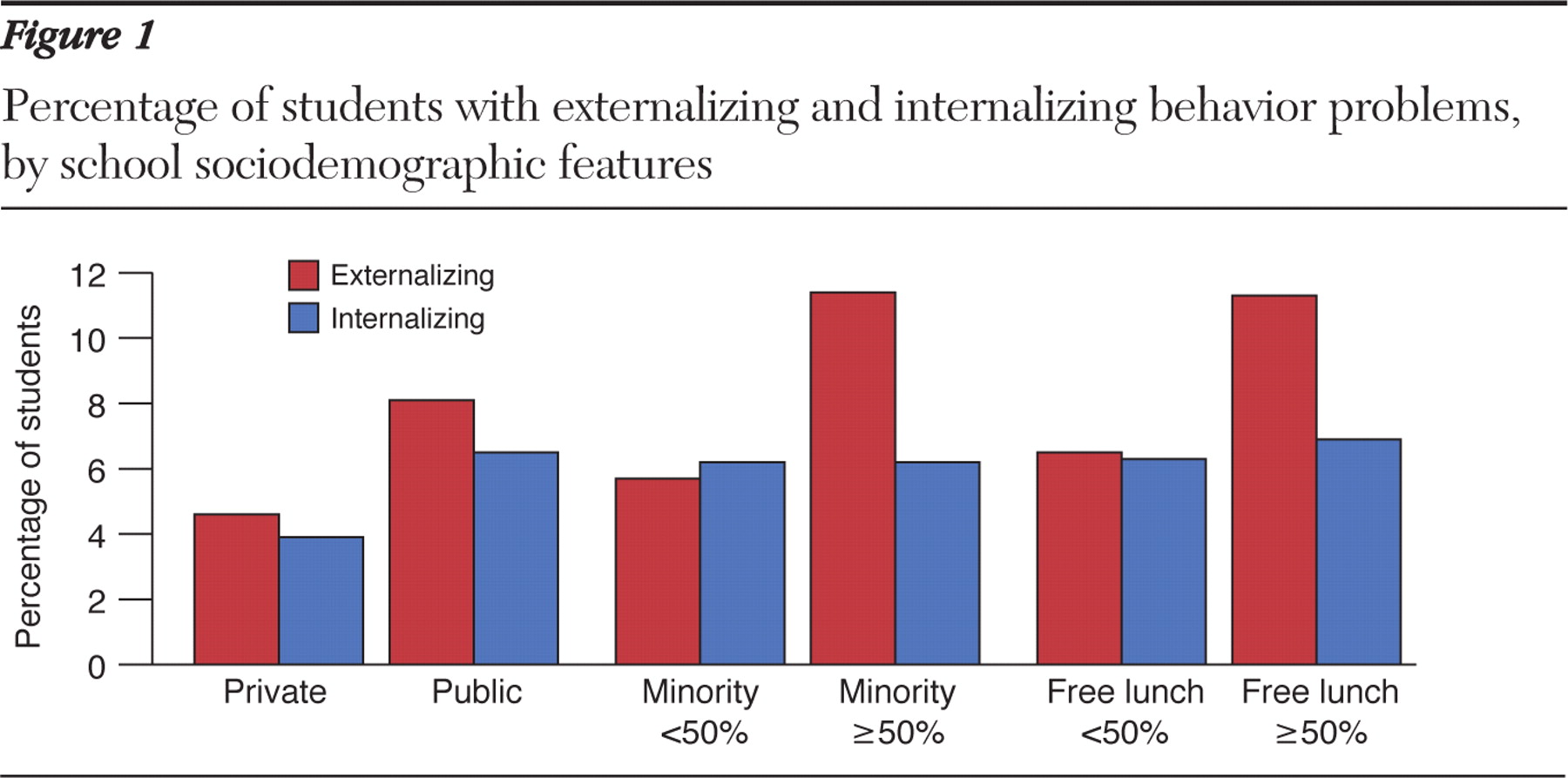

Figure 1 shows that public schools had significantly higher percentages of students with externalizing (8.1%) and internalizing (6.5%) behavior problems than private schools (4.6% and 3.9%, p<.001, respectively). These statistics were weighted to account for the differential sampling probabilities. Schools in which 50% or more of students were from minority groups had a much higher percentage of externalizing problems (11.4 %, p<.001) than schools with less than 50% (5.7%); however, no difference in internalizing problems was found. Finally, in schools where 50% or more of students were eligible for free lunch, 11.3% of students had external behavior problems, significantly higher than the 6.5% in schools in which less than 50% of students were eligible (p< .001); no difference in internal behavior problems was found.

The results of multilevel analysis to assess the nesting effect suggest that both individual- and school-level characteristics contributed to the variation in child behavior problems across schools. Of the total variation—11.5% observed across schools—6.1% was explained by individual-level characteristics and 21.3% was explained by school-level characteristics.

Our report suggests that school sociodemographic characteristics are associated with differential prevalence of behavior problems and that the association is stronger with externalizing behavior problems than with internalizing problems. Therefore, sociodemographic characteristics can help predict the need for corresponding intervention programs and help inform budgetary allocation. The use of school characteristics is an inexpensive and rather straightforward method for needs assessment.

Our study has some limitations. First, we found less significant predictive power when using child self-reported behaviors. Second, further research might aim to distinguish a school effect from a potential neighborhood effect.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was partly funded by grant P50-ES012383 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

The authors report no competing interests.