Independent variables

Four categories of independent variables were used: sociodemographic characteristics, type of disorder or chronic condition, occupational group, and province or region.

Sociodemographic indicators. Dummy variables were created for sex, marital status, and educational level. Age was included as a continuous variable.

Four socioeconomic status dummy variables (low income, lower middle, upper middle, and high income) were created on the basis of household size and income (

25 ). For example, a household of five or more people with an annual income of less than $30,000 was categorized as low income; the same was true of households of one or two people with an annual income of less than $15,000.

With regard to race or ethnicity, respondents were categorized into one of two categories—either white or nonwhite. The decision to create only two categories was based on the fact that the proportions of separate racial or ethnic groups were too small to be meaningful. Of the 22,118 persons in the sample, 19,584 persons (88.6%) were white. Of the 11.4% of workers who were not white, less than half were black (324 persons, or 1.5%), Asian (687 persons, or 3.1%), or Hispanic (113 persons, or .5%), with the remainder falling into seven other ethnic groups (1,382 persons, or 6.3%)—for example, West Asian or Native Canadian.

Disorders and chronic conditions. The CCHS-1.2 measured six psychiatric disorders falling into the broad categories of mood and anxiety disorders by using structured interview modules from the most recent Composite International Diagnostic Interview that were based on

DSM-IV criteria (

22,

26 ). The disorders included were depression, mania, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, and panic disorder.

The CCHS-1.2 also collected information about symptoms associated with addictions and eating problems. Problems with drugs, alcohol, and gambling were assessed by using modified versions of the World Mental Health 2000 interview modules (Ledrou I, personal communication, 2003). Problems with eating were assessed by using a version of the Eating Attitudes Test (

27 ). Although responses to these questions are not strictly interpretable as

DSM-IV mental disorders, they nevertheless indicate symptom levels strongly suggestive of the presence of disruptive or disordering problems.

Presence of any of the above disorders or problems in the past year was coded as 1 if it were present and as 0 if not.

The chronic physical condition indicator was scored as 1 if respondents affirmed having at least one chronic condition diagnosed by a health professional that lasted more than six months during the past year and as 0 otherwise. Conditions included asthma, fibromyalgia, arthritis, high blood pressure, chronic bronchitis, emphysema or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, epilepsy, heart disease, diabetes, cancer, stomach or intestinal ulcers, stroke, bowel disorder, chronic fatigue syndrome, or migraines.

A dummy variable for chronic work stress was created by using a single-item question that asked respondents to consider their main job or business and to rate whether they found most days in the past 12 months not at all stressful, not very stressful, a bit stressful, quite a bit stressful, or extremely stressful. Respondents in the last two categories were identified as experiencing chronic work stress. Thus, in these analyses, rather than a set of symptoms (that is, psychological distress), chronic work stress indicates the respondents' perceived exposure to stressful stimuli. That is, responses were reflective of how respondents viewed their work environments and job characteristics.

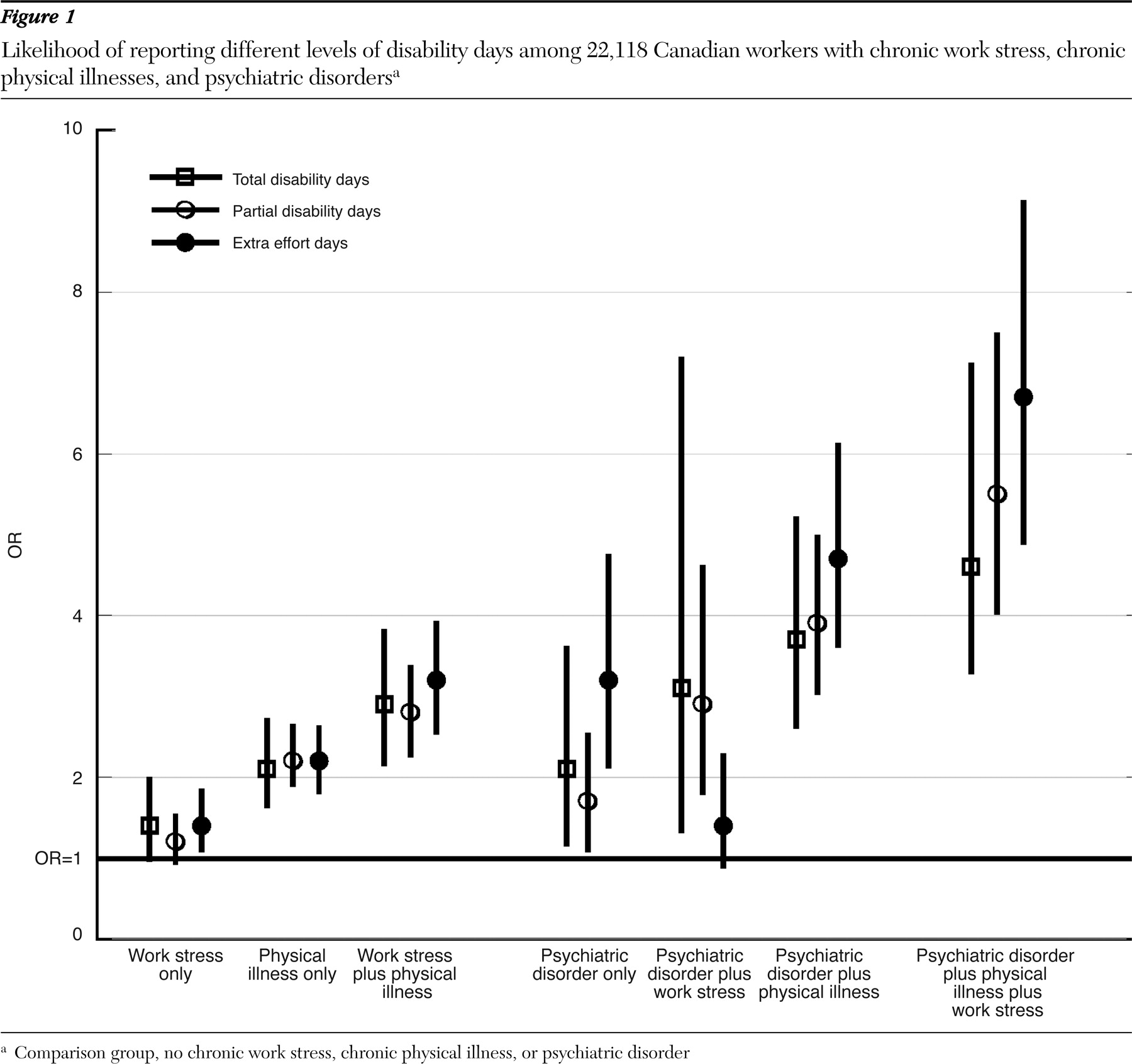

Because the conditions do not occur in isolation and are correlated, interaction terms were created to capture the effects of the presence of several conditions. Seven indicator variables for the presence of multiple conditions were created from the psychiatric disorder, chronic physical condition, and chronic work stress variables. These mutually exclusive variables were chronic work stress only, a chronic physical condition only, a psychiatric disorder only, a chronic physical condition plus chronic work stress, a psychiatric disorder plus chronic work stress, a psychiatric disorder plus a chronic physical condition, and chronic work stress plus a psychiatric disorder plus a chronic physical condition. Respondents with none of these conditions served as comparisons.

Occupational group indicators. Occupational dummy variables identified which of nine occupational groups respondents endorsed: manager, professional, technician, administration, sales, trades, farm, manufacturing, or other (

25 ).

Province or region indicators. Five province or region indicators were created to indicate the respondent's province or region of residence. These included British Columbia, the Prairies (the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba), Ontario, Quebéc, and the Maritimes (the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland).

Analyses

All analyses were done with SAS version 9. Descriptive characteristics of respondents who reported having a total disability day, a partial disability day, or an extra effort day were calculated. To compare the prevalence rates of psychiatric disorders, chronic work stress, chronic physical conditions, and combinations of these conditions, 95% confidence intervals for all estimates were calculated by using the bootstrap resampling SAS macro developed by Statistics Canada (

28 ) to account for the CCHS's complex sampling design. The bootstrap variance estimator is the standard deviation of the point estimates calculated for each of 500 samples by using the bootstrap weights.

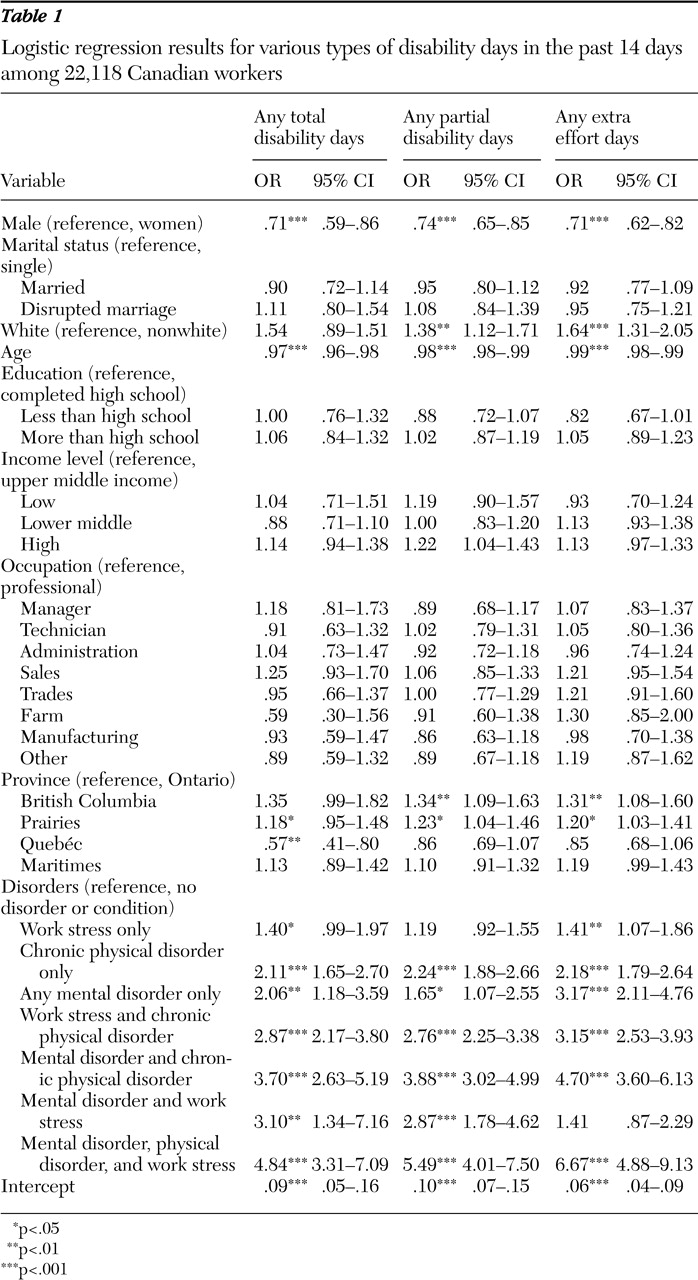

To examine the association of psychiatric disorders, chronic workplace stress, chronic physical conditions, and combinations of these conditions with disability among workers, logistic regressions were used that controlled for sociodemographic characteristics, province or region, and occupational grouping. Occupational dummy variables were used to control for unobserved factors on the basis of two assumptions. First, we assumed that participants' decisions to select their occupations were not made at random. As a result, choice of occupation may be linked to factors also associated with disability. Second, we assumed that occupation also reflects the workplace environment and characteristics that might be associated with disability. We used occupational status to generally adjust for unknown participant and workplace characteristics, particularly because our concern is the relationship between chronic work stress, health, and mental health status and disability rather than these other factors. Thus the occupational dummy variables were included to adjust our estimates for unobserved participant heterogeneity in much the same way as a fixed effects specification.