The groundbreaking World Health Organization (WHO) report on the global burden of disease (

1 ) with its identification of depression and other mental disorders as leading causes of disease burden has ignited renewed interest in studying the impact of these disorders on workforce availability and productivity. In a more recent WHO report (

2 ), depression was ranked as the fourth leading cause of disease burden worldwide, with predictions that it would become the second leading cause by 2020.

One approach to estimating the disability caused by mental disorders is to focus on the impact on employability and lost work time. Several studies, most using U.S. survey data, have examined the impact of depression and other disorders on rates of employment and work impairment (

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13 ). The 2001–2002 American Productivity Audit interviewed 3,351 work-eligible adults between the ages of 18 and 65 years. Workers with depression reported significantly more lost productivity time compared with those without depression (5.6 hours per week compared with 1.5 hours per week). Overall, 77% of individuals with depression reported some lost productivity time in the previous two weeks as a result of their illness (

3 ).

Within a large baseline sample of adults who worked more than 15 hours per week, Lerner and colleagues (

4 ) found higher rates of subsequent unemployment among individuals deemed to be depressed compared with those without depression and those with rheumatoid arthritis. A further analysis utilizing the Work Limitation Questionnaire identified more disabilities in occupations requiring proficiency in decision making and communication or frequent customer contact (

5 ). A series of analyses using data from the 1992 National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) revealed other trends in the relationship between mental illness and work-related disability. On average, overall employment rates were 11% lower among persons diagnosed as having a psychiatric disorder compared with those with no disorder (

6 ). Major depression, agoraphobia, and drug dependence were associated with the lowest rates of employment among men. In addition, annual income among working persons with a mental disorder was about $3,500 lower among women and $4,500 lower among men compared with persons in those groups with no disorder.

Other analyses conducted on data from the NCS and the earlier Epidemiologic Catchment Area Study (ECA) have focused on the impact of mental problems on lost work time among employed respondents. About 4% of ECA respondents reported at least one day in the past 90 days that they were unable to work because of emotional problems (

7 ). Data from the NCS revealed an average of six work-loss days per month per 100 workers that were due to psychiatric problems; affective disorders were associated with the most work impairment (

8 ).

In the replication of the NCS in 2002, participants diagnosed as having major depression reported an average of 35 days in the past year that they were unable to work or carry out their normal activities because of depression. Getting adequate treatment for depression reduced the proportion of days spent out of the normal role in cases with severe impairment from depression but not in cases with moderate or mild impairment (

9 ). Canadian epidemiological data on the impact of mental disorders on employment and disability are limited. A study of 9,953 Ontario residents revealed that workers with a history of depression were three times more likely than those in a control group to have sick days in the preceding month (

14 ).

The findings for the impact of substance-related disorders on work have been more inconsistent. Some studies have found that alcohol dependence had a negative impact on labor force participation, whereas others have reported a neutral or even positive impact (

6 ). Single and colleagues (

15 ) estimated that substance-related disorders overall cost Canadian society $11.8 billion (Canadian) in productivity losses, or about 1.7% of the gross domestic product in 1992. The WHO Global Burden of Disease study estimated that 4% of all disability adjusted life years (DALYs)—calculated by adding the years of life lost as a result of premature mortality and the years spent living with a disability—in 2000 could be attributed to alcohol-related disorders (

16 ).

It is important to acknowledge the strong association between mood and anxiety disorders and substance use disorders, a finding replicated across international studies (

17 ). An estimated 38% of all alcohol-attributable DALYs derive from the psychiatric consequences of substance dependence (

16 ). The original NCS showed that lost work days and work cutbacks (employee working at a reduced capacity) were significantly higher among persons with comorbid disorders than among those with only one disorder (

6 ). Furthermore, there have been no national, population-based estimates for Canada of the workforce burden of the most common mental disorders—that is, mood, anxiety, and substance-related disorders.

The objectives of this study were to estimate and compare the proportions working or not working and of reported activity restrictions among those with and those without mental and substance use disorders. This study also examined the associations between mental disorders and disorders related to substance use, occupational status, and disability. Although several previous studies have examined these questions, many have involved reanalyzing the same data sets. The objective of this analysis is to describe these associations by using newly available data: the Canadian Community Health Survey Cycle 1.2-Mental Health and Well-Being (CCHS-1.2).

Methods

CCHS-1.2

Detailed descriptions of the CCHS-1.2 in terms of target population, sampling procedures, response rate, and psychiatric assessment are available from other sources (

18 ). Briefly, the CCHS-1.2 was a cross-sectional survey of a nationally representative sample of individuals aged 15 years and older. The CCHS-1.2 data were collected by Statistics Canada in face-to-face interviews between May 2002 and December 2002 (N=36,984). The sample was selected according to a multistage stratified cluster design in which young persons and seniors were overrepresented. The response rates for the CCHS-1.2 were 87% at the household level and 77% at the individual level.

Clarifying the diagnoses involved

The CCHS-1.2 evaluated both lifetime and period prevalence. In this report, annual (past 12 months) period prevalence data were used. The disorders were defined by using

DSM-IV criteria (

19 ) and were assessed by using a Canadian adaptation of the World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMH-CIDI) (

20,

21 ), with the exception of substance dependence, which was evaluated with a short-form version of the CIDI. For analysis, mood disorders were aggregated into a single category. This included persons with either of the mood disorders evaluated in the survey: major depression or bipolar disorder, operationalized as past-year major depressive or manic episodes.

An anxiety disorder category included respondents meeting the

DSM-IV criteria for agoraphobia, panic disorder, or social phobia. Substance dependence was defined by meeting

DSM-III-R criteria for alcohol dependence on the CIDI short form or

DSM-IV criteria for drug dependence in the past 12 months, as defined by the WMH-CIDI. The specific substances covered were cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, MDMA (Ecstasy), hallucinogens, solvents, heroin, and steroids. Tobacco and prescription drugs were not included. The short-form alcohol dependence scale from the CIDI was tested extensively against

DSM-III-R criteria during the NCS (

22 ). Alcohol dependence, as defined in the CCHS-1.2, represents a purported 85% predictive cutoff point, corresponding to reporting at least three symptoms from the

DSM-III-R criteria.

A category for harmful alcohol use during the preceding 12 months was also defined because the version of the WMH-CIDI employed did not provide full coverage of

DSM symptoms for alcohol abuse. Therefore, we developed a separate algorithm for defining harmful alcohol use that was based on

ICD-10 criteria (

23 ): alcohol use has contributed to physical or psychological harm, leading to disability or adverse consequences; the nature of the harm is identifiable; the pattern of use has persisted for at least one month; and symptoms do not meet criteria for alcohol dependence. The CCHS-1.2 provided complete information regarding these symptoms.

The above categories excluded comorbid mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders. Instead, a separate category was defined for individuals with diagnoses in more than one of these categories.

The CCHS-1.2 interview included a series of questions about long-term medical conditions diagnosed by a health professional. This approach to assessment of chronic medical conditions has been shown to provide valid data for musculoskeletal conditions (

24 ).

Occupational status and disability assessment

Working status during the week preceding the interview was evaluated by using the following two questions: "Last week, did you work at a job or a business? Please include part-time jobs, seasonal work, contract work, self-employment, baby-sitting and any other paid work, regardless of the number of hours worked?" and "Last week, did you have a job or business from which you were absent?" Given the wording of the items, absence from work might include some people on vacation, homemakers, and students. We defined "not working" as either not working at a job in the past week or being permanently unable to work. Another item—"What was the main reason you were absent from work last week?"—identified work absences that were reported by persons as being due to their own illness or disability.

Finally, general functioning over the previous two weeks was assessed by using additional items that were not restricted in scope to occupational dysfunction: "How many days did you cut down on things for all or most of the day?" and "Was that due to your emotional or mental health or your use of alcohol or drugs?" Also, the following item was asked: "How many days did you stay in bed for all or most of the day?" followed by "Was that due to your emotional or mental health or your use of alcohol or drugs?" These disability questions, which focus on overall functioning rather than work-related impairment, have applicability for employed individuals as well as homemakers, students, and unemployed persons.

Before its initiation, CCHS-1.2 was reviewed for compliance with the stringent ethical and legal requirements of the Statistics Act and Privacy Act. These include a requirement that informed consent be obtained from all study participants. All stages of data collection, storage, linkage, and dissemination were audited both during and after completion of data collection (

25 ).

Analyses

All analyses were conducted in SAS 8.02 (

26 ). Analyses included all individuals between the ages of 18 and 64 who answered all relevant questions regarding mood, anxiety, and substance-related disorders as well as questions related to work and disability (N=27,332). The analysis was restricted to the 18- to 64-year-old age range because this was considered the age range most likely to be working. Prevalence estimates were calculated by using CCHS-1.2 sampling weights, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by using bootstrap procedures recommended by Statistics Canada to account for the survey's complex sampling procedures. The initial analysis included estimates of the overall frequencies of not working and disability and cross-tabulation with demographic variables. This was followed by stratified analysis within mental disorder groups to examine the associations within various sociodemographic strata. Logistic regression analysis was subsequently carried out in order to simultaneously adjust for the effects of other variables.

Next, we estimated the proportion of persons who attributed their not working to their own illness or disability. Finally, we examined the proportions reporting at least one disability day as a result of mental health problems or substance use.

Results

The variable describing harmful alcohol use that was derived for use in this analysis was not associated with any of the measures of workforce or functional status. This was true both for the crude estimates and for the adjusted estimates from the logistic regression analysis. Therefore, this variable was removed from the subsequent analyses. The estimates presented here include participants in the group without disorders.

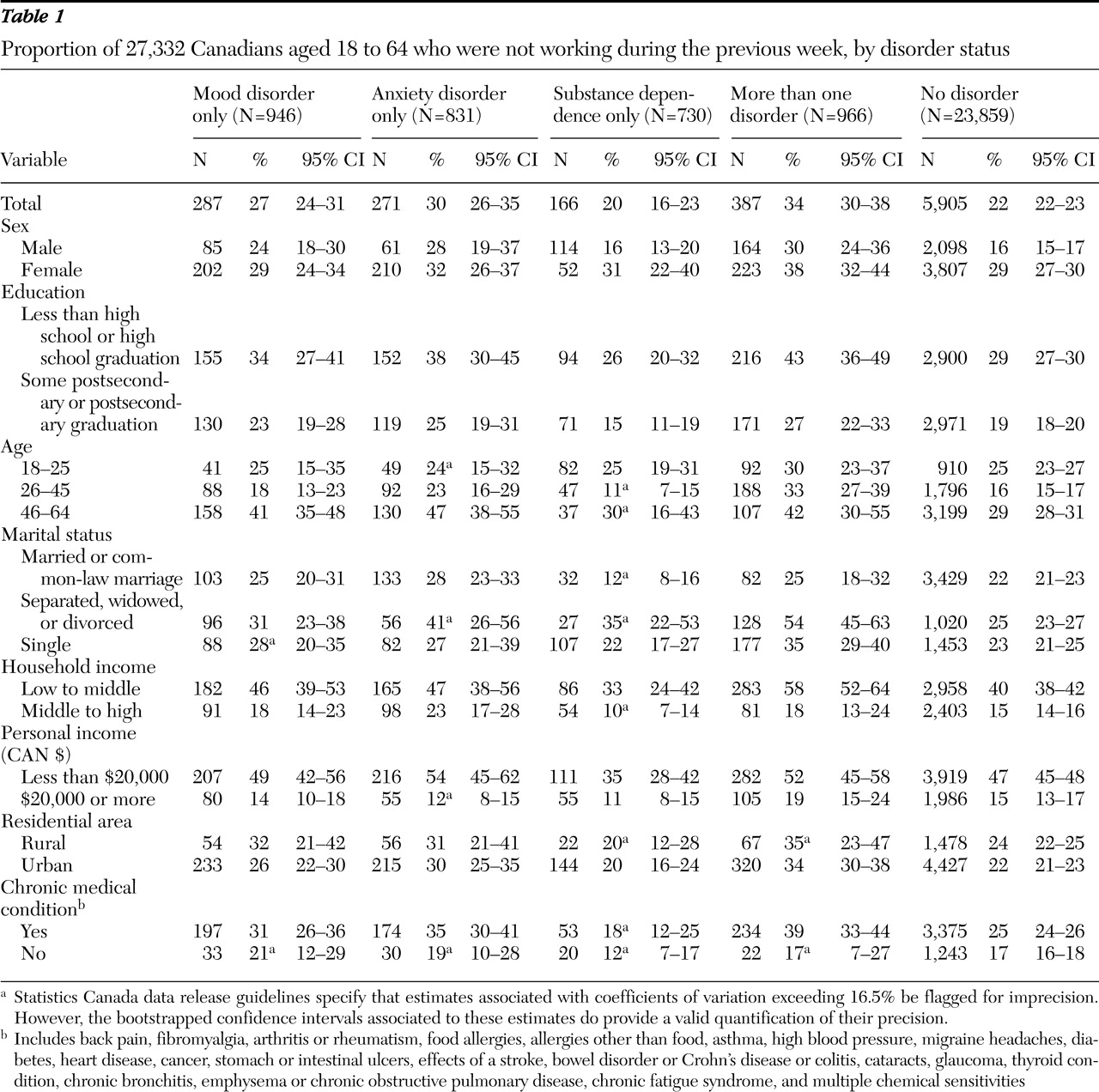

As described above, the component of the analysis concerned with absence from work was restricted to 27,332 members of the original survey sample (N=36,984) between the ages of 18 and 64 who answered the occupational status and disability questions. Overall, 7,016 persons (23.1%) (CI=22.3%–23.8%) reported that during the preceding week they were not at a job or were permanently unable to work. Among 23,859 persons without a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, or substance dependence, 22.2% reported not working in the week preceding the interview. A higher proportion of persons with a mood or anxiety disorder reported not working (

Table 1 ). Among those with mood disorders alone, 27.1% (CI=23.5%–30.7%) were not working. A similar proportion was seen among persons with anxiety disorders. Unlike persons with mood or anxiety disorders, persons with substance dependence did not have an elevated frequency of nonworking status according to the unadjusted analysis. These patterns were fairly consistently observed in various age-sex categories (

Table 1 ), with the possible exception of women with mood disorders alone, for whom the frequency resembled that of persons without a disorder. Also, the association appeared to be weaker after stratification for income, probably because of a close correlation between income and working status.

The frequency of nonworking status among persons with mood disorders was highest in the 46 to 64 age group, among those who were unmarried, and among those with personal incomes less than $20,000 per year. Also of note, the frequency of nonworking was higher for women.

Whereas

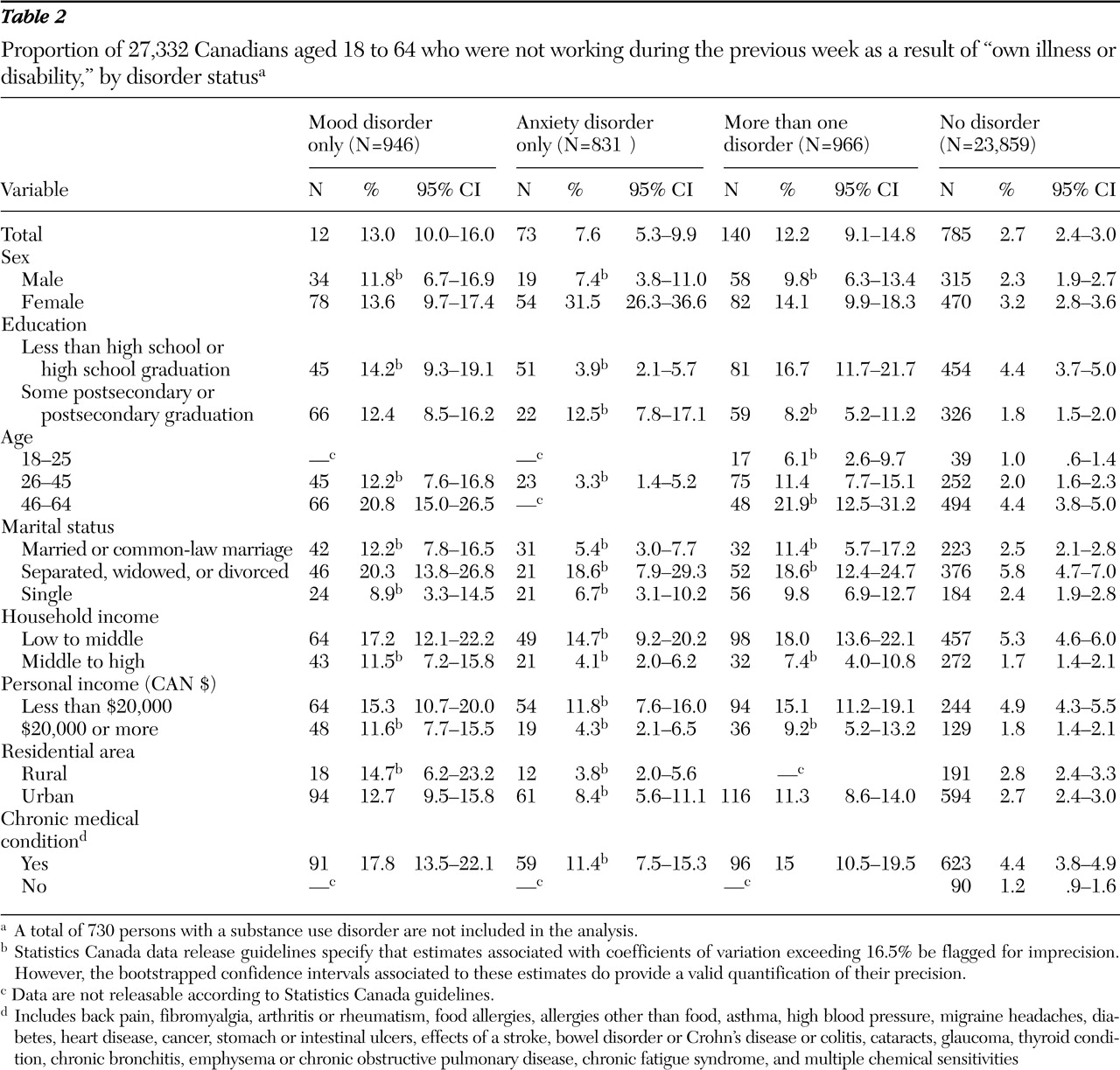

Table 1 reports the frequency of nonworking status during the week preceding the interview,

Table 2 presents the proportions that reported not working during the preceding week for reasons of "own illness or disability." Although overall 23.1% did not work at a job or business over the past week, only 1,110 (3.5%) reported that they had done so because of "illness or disability." However, the pattern remained constant in the sense that mood or anxiety disorders were consistently associated with not working because of illness or disability, whereas substance dependence and harmful alcohol use were not. A strong association of mood and anxiety disorders with not working as a result of illness or disability was observed for both men and women. It was not possible to estimate several of the frequencies for substance dependence in

Table 2 and

Table 3 because of sample size constraints, so these columns are not included in these tables.

Both

Tables 1 and

2 include a column for persons reporting more than one disorder. Unexpectedly, the frequency of not working as a result of illness or disability for comorbid disorders was similar to that observed for mood disorders.

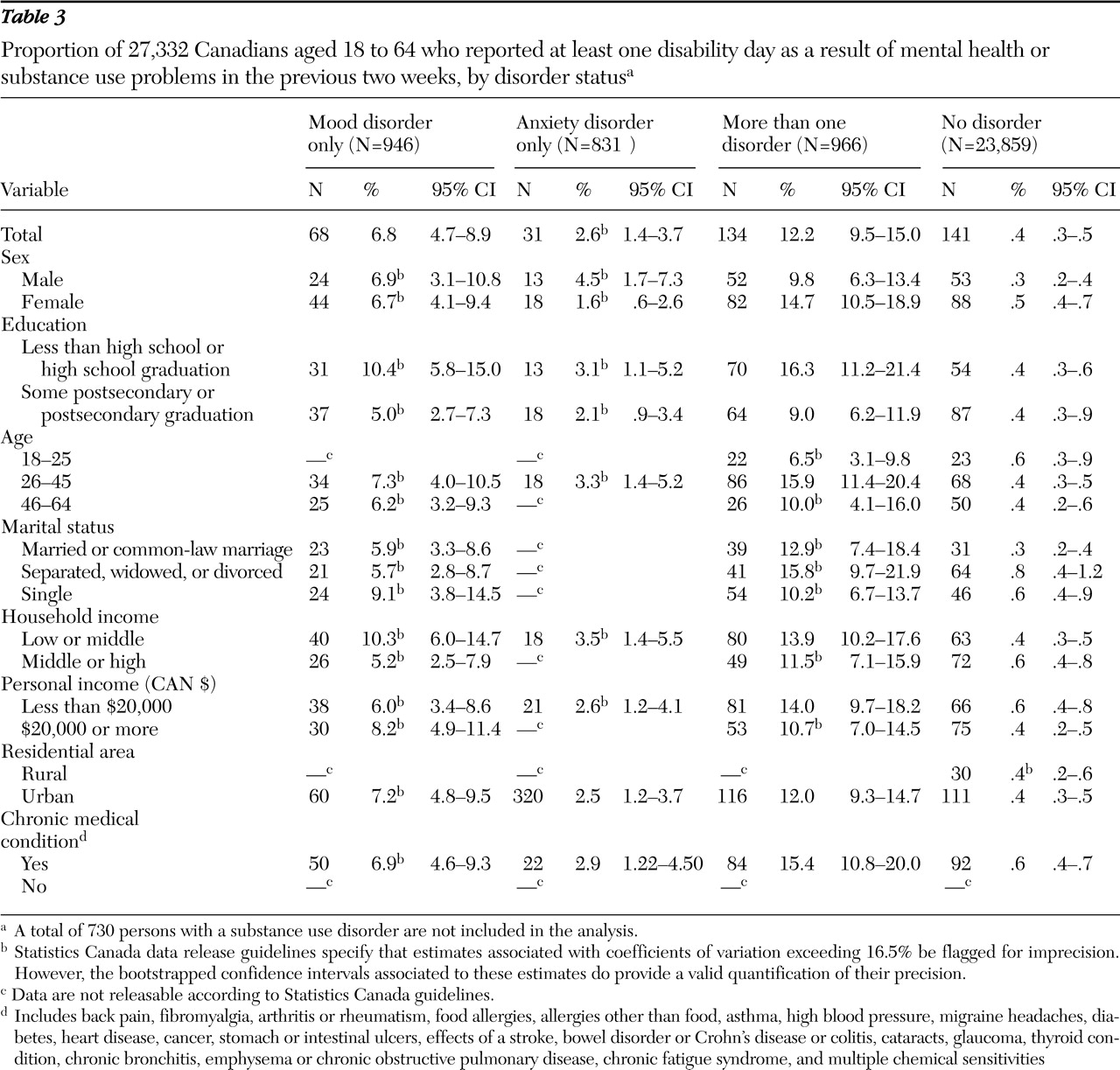

Table 3 presents the proportion of the sample reporting at least one disability day (that is, reduced activities or days spent in bed during the two weeks preceding the interview) as a result of mental health problems or substance abuse. Here, the pattern of association was different than that for not working during the preceding week. The main difference was that persons with substance dependence had an elevated frequency of reporting one or more disability day (24 persons, or 2.6%, CI=1.3%–3.8%), compared with persons with no disorder (.4%, CI=.3%–.5%). Less than 1% of persons with no disorder reported having disability or sick days.

In the analysis that was based on disability days, the impact of comorbidity was evident. At least 12% of persons with more than one disorder reported a disability or sick day in the past 14 days. This rate is higher than the rates for mood disorders alone (6.8%) or anxiety disorders alone (2.6%). The rate for substance dependence was equivalent to that for anxiety disorders. The CIs suggest that the elevated frequencies in these groups cannot be accounted for by chance.

In order to extend and integrate the results presented in the tables, logistic regression was used. A specific concern was whether an association of mood and anxiety disorders would persist after adjustment for other factors. After adjustment for self-reported chronic medical conditions, age, sex, education level, and marital status, having a mood or anxiety disorder was strongly associated with not working as a result of illness or disability during the week preceding the interview. There was an association with mood and anxiety disorders (OR=2.3, CI=1.8–2.9) and with being female (OR=3.1, CI=2.6–3.7), but there was also an interaction of mood or anxiety disorder and female (OR=.8, CI=.6–.9), indicating that although the association of mood and anxiety disorders with not working as a result of illness or disability was strong among both men and women (as initially suggested by data in

Table 2 ), the association among women was slightly smaller than the multiplicative risks associated with the two factors.

With adjustment for other variables in the model, an association with substance dependence emerged, although it remained weaker than that for mood and anxiety disorders (adjusted OR=1.4, CI=1.0–1.9). The CIs for this estimate include 1.0 because of rounding, but the association was significant (p=.03 for the Wald test). A similar logistic regression model for disability days confirmed the impressions gained from the stratified analysis: both the combined mood and anxiety disorder group and substance dependence were associated with disability or bed days related to mental health, the former more strongly than the latter. The adjusted OR for the combined mood or anxiety disorder category was 13.0 (CI=8.8–19.2), and for substance dependence it was 2.5 (CI=1.4–4.3).

The logistic regression for not working as a result of illness or disability was complex because of the presence of three significant interactions: female by mood or anxiety disorder, female by chronic medical condition, and age by chronic medical condition. There were no significant interactions in the model for disability or sick days, so that the main effects of a variety of predictors can be reported: chronic conditions (OR=2.6, CI=1.5–4.6), less than secondary-level education (OR=1.5, CI=1.1–2.2), single as marital status (OR=1.9, CI=1.3–3.0), and widowed, separated, or divorced as marital status (OR=1.6, CI=1.0–2.4). Age was included in these models as a continuous variable and was also associated with disability days.

Discussion

In this study we examined the association between mental disorders and various measures of nonparticipation in work and more general impairment in functioning. The results identified a consistent pattern, irrespective of the measure of functional impairment employed: both mood and anxiety disorders and substance dependence were associated with disability and impaired functioning. These findings are consistent with prior research on both U.S. and Canadian samples (

3,

4,

5,

8 ). In contrast to Parikh and colleagues (

14 ), who found that major depression increased the risk of sick days in the past month by a factor of three, we observed that persons with a 12-month diagnosis of a mood or anxiety disorder were approximately 13 times more likely than persons without a mood or anxiety disorder to report at least one disability day in the past two weeks. The higher OR found in the study presented here may be due to statistical adjustment for demographic and clinical factors. It could also follow from the fact that our study focused on disability as a result of mental health or substance use problems, whereas the Parikh study included all reasons for disability.

When nonworking status as a broad indicator of disability was used, our findings are consistent with those of Ettner and colleagues (

6 ). In their analysis lower rates of employment were independently associated with major depression and substance use disorder. Our findings indicate a stronger association between mood and anxiety disorders and nonworking status and disability than the association with substance disorder, but the lack of interactions in the models suggests independent effects. The stronger association of mood and anxiety disorders with employment rates may be due to characteristics of the conditions themselves. Alternatively, the CCHS-1.2 may have inadvertently selected "higher functioning" substance abusers who manage to retain employment despite having to take more days off because of their disorder. Highly transient, chronically unemployed persons with substance dependence (for example, homeless individuals) are not represented in a household survey such as the CCHS-1.2. It should be noted that our category for more than one disorder included a high proportion of cases with a mood or anxiety disorder comorbid with a substance use disorder. Unemployment rates in the group with more than one condition were significantly higher than the group with no disorders.

Because many other factors influence whether an individual has a job, employment rate is only a surrogate measure of disability. Fortunately, the CCHS-1.2 included more direct measures of functional disability. These results identified a consistent pattern, irrespective of the measure of functional impairment employed: both mood and anxiety disorders and substance dependence were associated with work-specific disability and impaired functioning when the analysis adjusted for relevant variables. In addition, the presence of more than one disorder was associated with the highest prevalence of functional impairment (as measured by the proportion reporting at least one disability day in the past two weeks), a finding consistent with Kessler and Frank (

8 ), although their study focused exclusively on work-related impairment among employed persons.

In terms of demographic correlates, nonworking rates were consistently elevated in the 46- to 64-year-old group across most diagnostic groups. However, the rate within this age range was also higher in the group with no disorders, and one might imagine that some people in this age group took early retirement. Only the mood disorder and anxiety disorder groups had significantly higher nonworking rates than the group with no disorders in the upper age range. Persons in the lower income category consistently had higher rates of nonworking status, work-related disability, and functional impairment across all groups. Enhanced social vulnerability may also interact with the disorders' impact. In terms of gender trends, women who abused substances had a higher rate of not working in the preceding week than men in the same category. Additionally, among persons with anxiety disorder, women were more likely than men to attribute not working to their illness, compared with the group with no disorders. The higher rate of unemployment among women with no disorders in the sample is consistent with general labor-force trends in North America.

Isolating the effect of mental disorders on occupation status would require control for all potentially confounding variables. In this context, a confounding variable could be any determinant of occupational status with effects independent from those of mental disorders. In order to act as a confounder, such a variable would also need to be associated with mental disorder prevalence. Controlling for all such variables would require a more detailed data set and longitudinal data collection. As the goals of this study were descriptive, we have reported estimates that were adjusted for important descriptive variables because these models provide additional descriptive data. These should not be regarded as an attempt to isolate specific causal pathways.

The CCHS-1.2 version of the CIDI did not include a diagnostic module for assessing generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or dysthymic disorder. Furthermore, the illicit drug section of the CCHS-1.2 did not provide sufficient coverage of symptoms to define a category of harmful drug use. The absence of data on these conditions is a limitation of the survey, as is the absence of treatment data. The CCHS is also subject to the usual interpretive limitations resulting from its cross-sectional study design. Prominent among these is the lack of information provided by cross-sectional data about temporal relationships. It is possible, for example, that not working may contribute to the emergence of mental disorders, so the results cannot be interpreted in a unidirectional way: as evidence that mental disorders cause occupational disruption. Estimates deriving from cross-sectional data can also be impacted by factors such as prognosis and mortality. For example, if not working increases the duration of mood and anxiety disorder episodes, then an association could emerge in cross-sectional data even in the absence of a change in risk. Because treatment may mediate between a diagnosis and the resulting functional impairment, the lack of treatment data is another limitation of this analysis.

Several explanations may account for the stronger association observed for mood and anxiety disorders than for substance use disorder. The impairment resulting from mood and anxiety disorders tends to be highly persistent, whereas it is possible that substance-related impairment is more variable. For example, some of the impairment resulting from substance dependence may occur during intoxication or withdrawal, and some people may be able to manage their work schedules in compensatory ways—for example, by timing their substance use to avoid intoxication or withdrawal while they are at work. Also, because purchasing abused substances requires financial resources, a need for money may foster perseverance at work. People with substance dependence may not always attribute workplace difficulties to their substance use. Finally, if support for work absence resulting from illness is more available to people with mood and anxiety disorders, leaving the workplace because of one of these disorders may be more feasible for people with these disorders than for those with substance dependence.

Although the WMH-CIDI is considered a state-of-the-art structured diagnostic interview, it is subject to the limitations associated with fully structured interviews. The administration of this interview by lay interviewers cannot incorporate diagnostic judgment, and the interviewers cannot probe for more detail or deviate from the interview script in order to pursue additional information. In epidemiology, bias resulting from misclassification is often in the direction of no effect. It is possible that misclassification bias has caused some of the reported associations to appear weaker than they actually are.

Across all diagnostic groups a large discrepancy was revealed in the prevalence rates for being out of work in general and being out of work because of illness or disability. For example, 27.1% of individuals with a mood disorder had not worked in the previous week but only 13.0%, about half of these, attributed being out of work to illness or disability. This result is not necessarily surprising because functional impairment and disability have many determinants that may be interrelated and comprise separate elements of causal mechanisms. It should also be acknowledged that the group that was not working may include people who are not working for reasons other than impairment, such as being a student. For example, having a chronic medical condition may increase the risk of developing depression, and depression may detract from a person's capacity to cope with the challenges of functioning despite a chronic medical condition. The findings reported here draw attention to the need for detailed prospective occupational studies to clarify the underlying mechanisms. Identification of causal factors would facilitate the development of preventive strategies. However, cross-sectional data remain valuable for quantifying the extent of labor-force disruption that occurs among people with mental disorders.

Finally, in this study prevalence figures for mental disorders included persons with past-year diagnoses, whereas the employment questions focused on the previous week. It is possible that many individuals in the diagnostic groups were in a period of recovery from their disorder and did not attribute changes in their employment status to mental illness.

Although we have provided detailed interpretations of the CCHS-1.2 results, it should be acknowledged that the findings reported here are subject to limitations inherent in the design of most large mental health surveys, principally its cross-sectional nature and lack of full coverage of all potentially relevant variables. For example, it is possible that some of the associations will not be replicated by longitudinal studies and that the pattern of association may change with the inclusion of additional variables in the analysis. The results presented here will increase in credibility if they can be replicated in other populations and in studies with different methodological features.

Conclusions

Although physical disability is known to be an important determinant of labor-market outcomes, this article adds to the body of evidence describing the significant influence of mental and substance use disorders on work impairment. The adverse labor-force consequences support the economic argument in addition to the humane one for providing accessible treatment for mental and substance use disorders to members of the workforce.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant ACC-65800 from the Canadian Institute of Health Research. The analysis was based on data collected by Statistics Canada, but the analysis and conclusions are those of the authors and not Statistics Canada.

The authors report no competing interests.