Participants

Participants were from a longitudinal, community-based study of mothers with severe mental illness (

7 ) who were interviewed in three waves, each approximately 20 months apart over a period of six years (1995–2000). Participants were recruited from 12 community agencies and three psychiatric units in a large metropolitan city in southeastern Michigan. Criteria for study inclusion were being female, having a

DSM-IV diagnosis of severe mental illness, being 18 to 55 years old, caring for at least one child between ages four to 16 years, and having an active case at study initiation (

7 ). In this study we focused on the interviews conducted at the first wave (baseline) and the second wave (follow-up). A total of 379 women participated at baseline, and 324 (85%) participated at follow-up. This study focused on the 324 women with data from both waves.

Procedure

Interviewers were all women with at least an undergraduate degree in the human services. They were supervised by an interview coordinator, who ensured interview quality by reviewing audiotapes and checking completed forms. All interviews took place in the participants' homes, and the women were compensated $15 for each interview at baseline (at baseline, a two-part interview session was conducted one or two weeks apart between 1995 and 1996) and $30 for the follow-up session (interviews were conducted between 1997 and 1998). More detailed information on the sample recruitment procedures are described elsewhere (

7,

28 ). All participating women provided voluntary informed consent. The study was approved by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Names of eligible women were obtained from inpatient and outpatient public mental health agencies through case-manager referrals and record searches. To enroll clients in the study, eligible women were contacted either by a community mental health employee funded through the project or by their community mental health case managers. Women in inpatient units were recruited on the wards and interviewed 30 days later. A follow-up interview was conducted 20 months after baseline. At follow-up, 324 women completed interviews, 25 refused, 23 could not be located, and seven had died, leaving a completion rate of 85%.

Sample characteristics

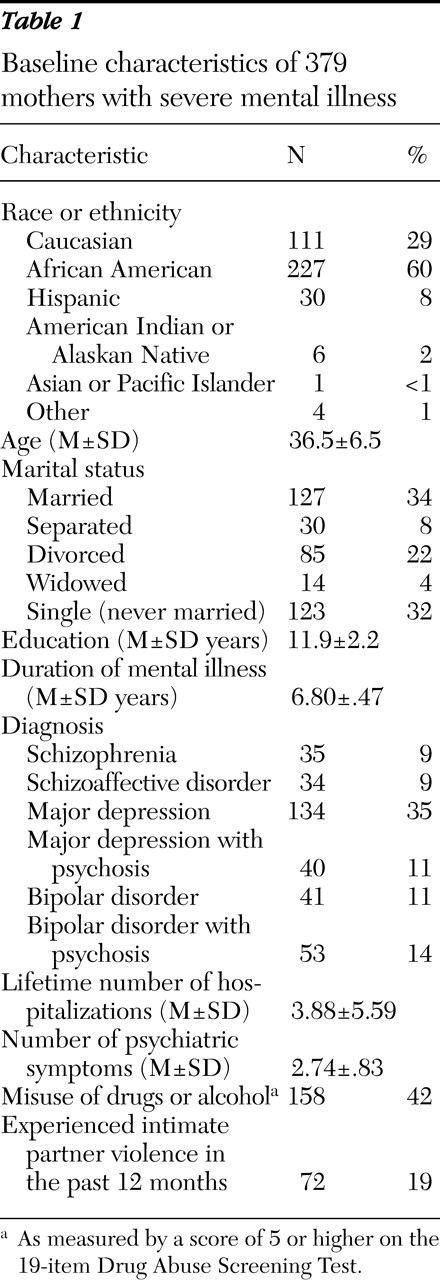

As shown in

Table 1, of the 379 participants at baseline, 337 met

DSM-IV criteria for having one of six lifetime diagnoses, including schizophrenia (9%), schizoaffective disorder (9%), major depression (35%), major depression with psychotic features (11%), bipolar disorder (11%), and bipolar disorder with psychotic features (14%). The 42 women (11%) with no research diagnosis included 14 women who did not complete the diagnostic interview and 28 women for whom the interview yielded insufficient information for diagnostic determination. The median age reported for onset of mental illness was 27 years. Age of onset was measured by first psychiatric hospitalization, or alternately, those without psychiatric hospitalizations were asked for the age at which they first saw a psychiatrist or other mental health professional.

Sixty percent of the participants were African American, 29% were Caucasian, 8% were Hispanic, and 3% were of other racial or ethnic backgrounds. For purposes of this analysis, race or ethnicity was coded as 1 for African Americans and 0 for Caucasians, Hispanics, and others collapsed into one group. A total of 153 participants (40%) had some college education or more, 93 (25%) had a high school diploma or GED, and 133 (35%) had less than a high school education. Participants' median age was 36.5 years.

All participants had at least one child between the ages of four and 16 for whom they had child care responsibilities, defined as having overnight contact at least once a week. Respondents reported having a median number of three children with a median age of 11 years (ranging from infancy to adulthood). Seventy-five participants (20%) had only one child, 197 (52%) had two or three children, and 106 (28%) had more than three children. A total of 127 participants (34%) were married or living with a partner; 129 (34%) were separated, divorced, or widowed; and the remaining 123 (32%) were single, having never married. The median family income was $929 a month. After the analysis adjusted for individual women's household composition, 261 participants (69%) fell below the federal poverty threshold—that is, a mother with one child receiving $10,815 annually.

Measures

At baseline two interview sessions were conducted with each of the 379 participants (one or two weeks apart, on average), lasting about 60 to 90 minutes each. The material was divided between two interview sessions to ensure that all critical information was gathered in the first interview, should the participant not be interviewed a second time. Information gathered in the first session covered personal history, parenting, social context, and community functioning. The second part (N=324) contained modules of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule (

29 ) and a slightly modified version of the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) (

30 ).

The study's dependent variable, intimate partner violence, was originally constructed by project staff to reflect the content of the physical violence items from the Conflict Tactics Scales (

31 ). At follow-up, the participants were asked four questions: Over the past 12 months did someone you were romantically involved with ever push, grab, or slap you? Did they ever hit you with a fist or an object, kick you, or beat you up? Did they ever choke you, tie you up, or physically restrain you? Did they ever force sexual activity that you didn't want to happen? Intimate partner violence for this study was measured by whether the participant reported the experience of any violence by a romantic partner over the past 12 months (coded as 1, yes, or 0, no).

The study's main independent variable, substance use disorder, was measured with a modified version of the DAST. Unlike the original 20-item DAST, our version included 19 questions that asked participants to report on their lifetime history of substance use, including alcohol.

The study of mothers with severe mental illness used the 20-item version of the DAST and adapted it as described below to be appropriate for use with mothers with mental illness. In general, the word alcohol was added to all the questions. One original question was split into two: Question 11 from the DAST—"Have you ever neglected your family or missed work because of your use of drugs?"—was split into "Have you ever neglected your family obligations because you have been using drugs and alcohol?" and "Have you ever missed work because you have been using drugs or alcohol?" This was done so that specific information about family neglect could be collected and separated from work issues. Questions 12 and 13 of the DAST were combined into one question: "Have you ever been in trouble at work or lost a job because of drug and alcohol use?" This was done because few women in the sample were working or had worked. Questions 19 and 20 were combined into one question: "Have you ever gone to anyone for help or been involved in a treatment program for a drug or alcohol problem?"

Mothers were asked whether they had used ever used alcohol or any drugs, such as illicit drugs, had ever used nonmedical drugs, had ever used prescribed or over-the-counter drugs in excess of the directions, and had experienced drug-related problems in the past 12 months. A cutoff score of 5, rather than 6 as customary, was utilized to indicate whether there was a history of any past problems with alcohol or drugs. This lower cutoff point was used because we had reduced by 1 the total DAST score that could be obtained. Also, as suggested in the literature, lower cutoff scores in psychiatric populations are appropriate (

32 ). The reliability estimate of the 19-item DAST in our sample was

α =.94 (mean±SD correct items=5.01±4.76).

Control variables included race or ethnicity, age, marital status, and level of education. Marital status was a dummy variable, coded as 1, for single, separated, or divorced, and 0, for married or widowed. Clinical variables included number of lifetime hospitalizations (from date of first psychiatric hospitalization or first contact with a psychiatrist or other mental health professional), and duration of mental illness was calculated by using the difference between the date respondents reported first having seen a psychiatrist or other mental health professional and the date of the initial interview (coded for this analysis as 0, less than five years, or 1, five or more years). The diagnostic portion of the interview consisted of the depression, mania, and psychosis sections of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, version III-R, modified for

DSM-IV criteria. For the analysis presented here, diagnostic categories used in this study were dichotomized into affective disorders (major depression and bipolar disorder without psychotic features) and psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, major depression with psychotic features, and bipolar disorder with psychotic features) (coded as 0, psychotic disorders, or 1, affective disorders). Psychiatric symptomatology was measured by using the Colorado Symptom Index (

33 ).