Prostitution and substance abuse are strongly linked (

1,

2,

3 ). A study of nearly 5,000 adults entering substance abuse treatment in the United States found that 51% of women and 19% of men reported prostitution at some point in their lives (

4 ). Given the legal, social, and mental health issues associated with prostitution among women (

5,

6 ), their substance abuse treatment needs may differ markedly from those of women not involved in prostitution. Several studies have examined the influence of prior trauma exposure on women's substance abuse treatment (

7,

8 ); however, similar research on prostitution and substance abuse treatment has not been published.

Criteria of the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) recommend that substance abuse treatment providers tailor the treatment setting and services to address patients' co-occurring legal and social problems (

9 ). Prostitution poses legal issues and is linked with socioeconomic problems, such as lower educational attainment, homelessness, and unemployment (

1,

6 ). Women involved in prostitution exhibit severe patterns of substance abuse, including intravenous drug use, polysubstance abuse, and substance-related health problems (

1,

2,

3 ). Furthermore, prostitution may be associated with a constellation of environmental risk factors for poor mental health. Women involved in prostitution report high rates of exposure to violence and intimidation at the hands of clients and pimps and are at risk of depression and trauma-related disorders (

5,

10 ).

The profile of social, legal, and psychological problems associated with prostitution suggests that prostitution may carry with it a distinct set of treatment needs. Furthermore, the prostitution lifestyle, characterized by frequent exposure to illicit substances, homelessness, and threats of physical harm, may present distinctive barriers for women who attempt to overcome substance abuse problems (

2,

3,

10 ). However, research on how prostitution and its co-occurring problems are addressed within substance abuse treatment programs is lacking.

We examined whether women who were involved in prostitution received more comprehensive treatment services during an episode of substance abuse treatment compared with women who were not involved in prostitution. First, we tested whether prostitution was associated with a greater likelihood of entering residential treatment compared with outpatient treatment. Next, within each treatment modality, we examined whether prostitution was associated with differences in the duration of treatment and the amounts of psychological, medical, and psychosocial services received.

Methods

Data were from the National Treatment Improvement Evaluation Study (NTIES), a multisite, five-year (1992–1997) evaluation of 79 substance abuse treatment programs. The NTIES sample is comparable to samples in other large-scale substance abuse treatment studies in demographic characteristics and baseline substance abuse severity (

11 ). Secondary data analyses were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. Sampling methods and procedures have been described elsewhere (

4,

11 ). Participants completed a structured interview upon entering treatment, and patient files were accessed upon completion of the study to record service use during the treatment episode.

The original sample included 1,840 women. We limited our analyses to women old enough to consent to sexual activity; those under age 18 (N=66) were excluded. Because incarceration status could limit opportunities to engage in prostitution, we excluded incarcerated women (N=165). Finally, we excluded women who refused to provide information on prostitution (N=5). The final sample consisted of 1,604 women.

Baseline prostitution was defined as having sex in exchange for money or drugs at least once in the past year. Baseline substance use was assessed by asking how many days in the past month patients used marijuana, crack, cocaine, heroin, or other narcotics (0, none; 1, once; 2, two to five times; 3, six to ten times; 4, 11 to 20 times; or 5, 21 or more times). Scores were summed across substances to create a continuous index of frequency and diversity of substance use (range 0 to 25).

Treatment modality (residential or outpatient) and duration (months of stay for residential or months enrolled for outpatient) were recorded from patient files after discharge. Consistent with previous studies of this sample, inpatient and residential programs were combined into the single category of residential (

12 ).

NTIES staff coded the number of times patients received various types of services while they were in the residential or outpatient treatment program (0, no services; 1, once; 2, two to three times; 3, four to ten times; 4, 11 or more times). Scores were summed across items to create three indices. The medical index consisted of four items; possible scores ranged from 0 to 16. The items addressed intake by a physician or nurse, other physician services, care by a nurse or nurse practitioner, and AIDS education. The mental health index consisted of seven items; possible scores ranged from 0 to 28. The items addressed treatment by a psychiatrist or psychologist, individual counseling, group counseling, family counseling, self-help groups, interpersonal skills training, and postdischarge planning. The psychosocial index consisted of ten items; possible scores ranged from 0 to 40. The items addressed employment counseling, job training, academic training, practical skills training, parenting skills training, benefit assistance, legal services, transportation services, housing assistance, and room and board services.

In keeping with U.S. Census definitions, NTIES coded race-ethnicity as non-Hispanic nonblack, Hispanic nonblack, and non-Hispanic black. Women were asked whether they had obtained a high school diploma or equivalency degree, were employed, or had stayed in a homeless shelter in the year before entering treatment.

Analyses were conducted in SPSS version 11.5. Chi square or t tests were used to compare women who were involved in prostitution with those who were not. Multiple regression analyses estimated the influence of prostitution on outcomes after adjustment for covariates. Specifically, logistic regression was conducted to predict entry into residential treatment from prostitution status, with adjustment for baseline substance use and demographic characteristics. Linear regressions were conducted within treatment modality to determine whether length of stay differed by prostitution status, with adjustment for baseline substance use and demographic characteristics. Linear regressions were also used to examine whether prostitution predicted differences in amounts of services obtained, with adjustment for baseline substance use, demographic characteristics, and treatment duration. Duration of stay and service indices were log-transformed in regressions to meet assumptions of normality. Pairwise deletion was used for missing data, which resulted from incomplete file information.

Results

Overall, 42% of women (N=667) reported past-year involvement in prostitution at baseline; 71% of these women (N=471) had engaged in prostitution more than five times. Women reporting prostitution were more likely to be black (78% [N=521] compared with 56% [N=524] of the women not involved in prostitution; χ 2 =85.5, df=1, p<.01). Women reporting prostitution were less likely to have a high school diploma (48% [N=317] compared with 55% [N=512]; χ 2 =7.9, df=1, p<.01) or to be employed (6% [N=37] compared with 14% [N=134]; χ 2 =31.4, df=1, p<.01), and more likely to be homeless in the previous year (32% [N=215] compared with 12% [N=111]; χ 2 =100.0, df=1, p<.01). In addition, those who reported prostitution were younger than those who did not report prostitution at baseline (mean±SD age of 31.0±5.7 compared with 33.0±7.8; t=–5.9, df=1,602, p<.01). Women involved in prostitution also reported a greater number of past episodes of substance abuse at treatment (3.2±3.5 compared with 2.6±3.3; t=3.7, df=1,602, p<.01).

In bivariate comparisons, women who reported prostitution at baseline were more likely than women not involved in prostitution to enter residential treatment (69% [N=458] compared with 48% [N=451]; χ 2 =66, df=1, p<.01). For those who entered residential programs, women involved in prostitution did not differ from women not involved in prostitution in duration of residential treatment (3.1±5.4 compared with 3.2±4.3 months) or amount of medical services (3.6±2.6 compared with 3.8±2.8) and mental health services (11.5±5.9 compared with 12.2±6.1) received during treatment. However, women involved in prostitution received fewer psychosocial services while in residential treatment (5.6±5.2 compared with 7.4±6.8; t=–4.3, df=900, p<.01).

For women who entered outpatient programs, treatment duration did not differ between women who were involved in prostitution and those who were not (5.2±4.6 compared 5.8±5.8 months). Those involved in prostitution did not receive more medical services (1.6±1.7 compared with 1.4±1.7); however, they did receive more mental health services (7.6±5.9 compared with 6.4±4.7; t=2.71, df=662, p<.01) and psychosocial services (2.2±3.2 versus 1.1±2.2; t=4.8; df=655, p<.01).

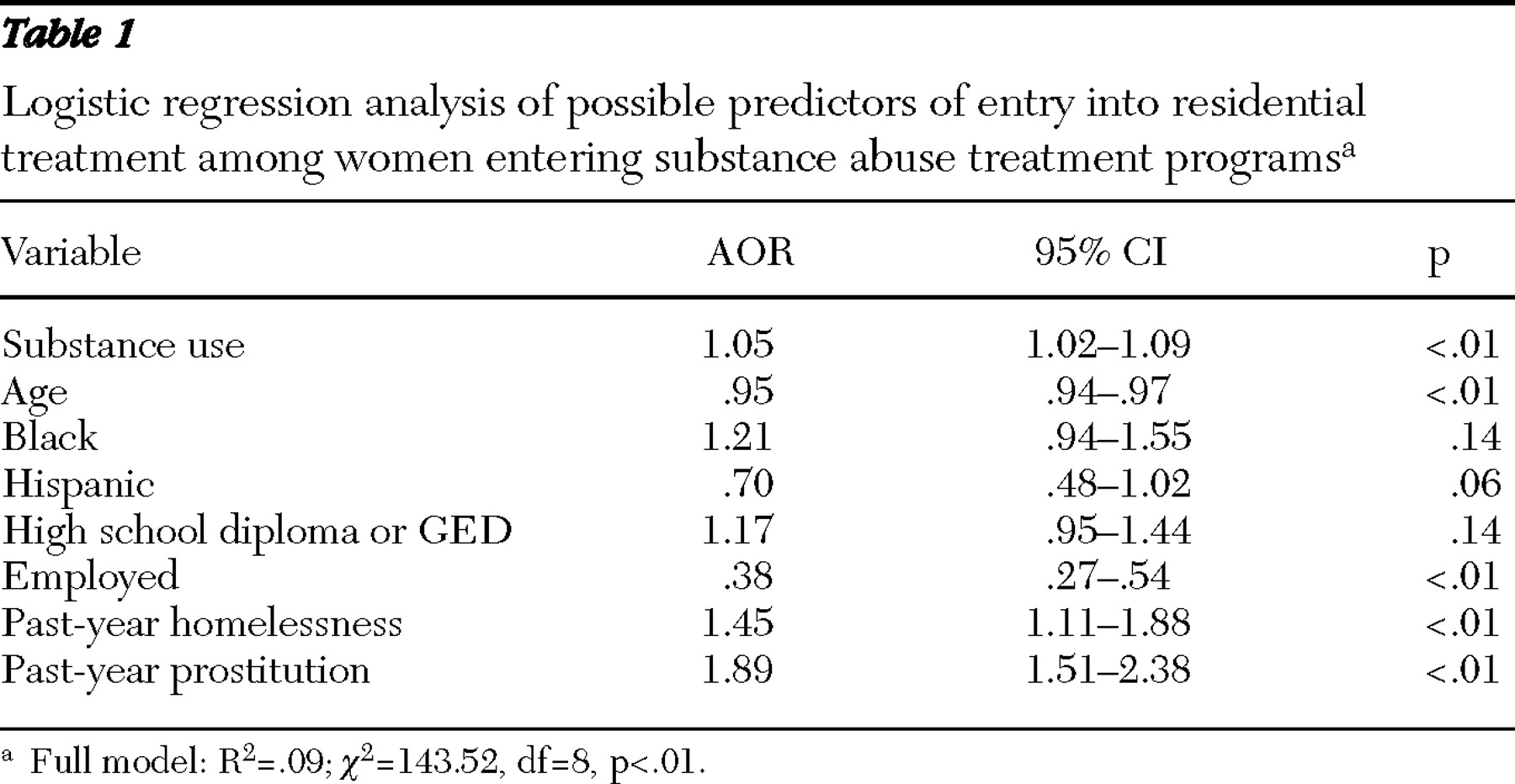

Results of the logistic regression analyses are shown in

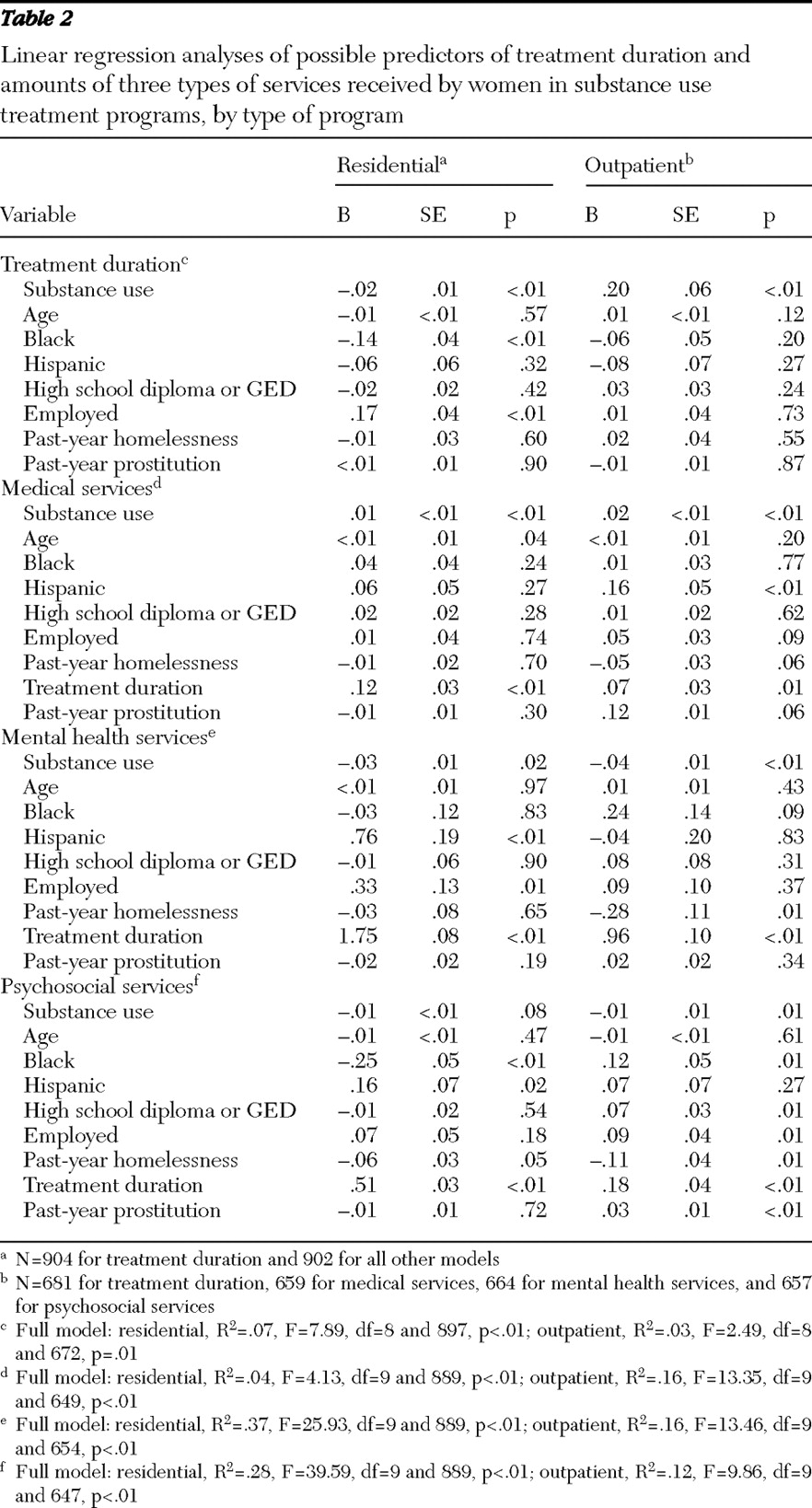

Table 1 . As shown, women involved in prostitution had nearly twice the odds (adjusted odds ratio=1.89) of entering a residential treatment program compared with women not involved in prostitution. Results of the linear regression analyses are shown in

Table 2 . For women who entered residential programs, prostitution was not associated with differences in duration of treatment or amounts of services received. For women who entered outpatient programs, prostitution was not associated with differences in duration of treatment or receipt of medical or mental health services; however, it was associated with receipt of more psychosocial services.

Discussion

Substance abuse programs appear to respond to the comprehensive treatment needs of women involved in prostitution by providing residential programming (including inpatient treatment) or more psychosocial services within outpatient treatment programs. Specifically, past-year prostitution was associated with an increased likelihood of entering residential treatment, as well as the receipt of more psychosocial services among women who entered outpatient treatment. These findings held even after the analyses adjusted for homelessness, substance use frequency, and sociodemographic factors.

Given the array and magnitude of problems facing women involved in prostitution (

1,

10 ), residential care may be an important first step in their long-term substance abuse treatment. Such treatment allows women to be removed from a maladaptive environment and to be provided with the types of comprehensive services that are needed to address a wide range of mental health and substance abuse symptoms.

Alternatively, outpatient treatment may represent a more palatable option for some women. Outpatient treatment can approximate the intensity of residential treatment by the provision of more medical, mental health, and psychosocial services. Multipronged approaches may be needed; medical interventions and education about the spread of diseases can reduce transmission of HIV among women involved in prostitution (

13 ), and psychosocial rehabilitation may simultaneously help women build new lives outside of prostitution (

14 ). In addition, time-limited motivational interventions have been shown to reduce prostitution and substance abuse among women engaging in prostitution and could be used as part of outreach strategies to increase treatment initiation (

15 ).

The study reported here represents only a first step toward better serving the population of women who abuse substances and who report involvement in prostitution. Although substance abuse treatment programs appear responsive to the substantial needs of these women, research is still needed to determine the extent to which additional services improve treatment outcomes for women previously involved in prostitution.

This study was exploratory, and several limitations should be noted and addressed in future studies. First, the process by which women were referred to treatment or specific types of services is unknown. Therefore, other factors may account for observed differences, including level of income, insurance coverage, or other patient characteristics. In particular, our measure of baseline substance use severity was limited to frequency and variety of substances used and may not adequately characterize severity. Subsequent studies should assess the extent of physiological symptoms and health problems associated with substance abuse (for example, tolerance and withdrawal, urges and cravings, and impairment in functioning) and examine their association with prostitution and service provision. This study assessed involvement in prostitution by self-report in a face-to-face interview. Given the social stigma associated with prostitution, such methods may underestimate its true prevalence. We also lacked information on providers' knowledge of patient involvement in prostitution and were unable to evaluate the direct association between this knowledge and treatment recommendations. Finally, our study was limited to a population of women who were already entering treatment, a population likely to differ from the larger population of women abusing substances who are involved in prostitution but who do not seek or cannot access substance abuse treatment (

3 ).

Conclusions

The findings suggest that women involved in prostitution before entering substance abuse treatment are more likely to receive residential care than women not involved in prostitution. When they are treated in outpatient settings, they are likely to receive more psychosocial services. Such findings are consistent with ASAM treatment guidelines (

9 ), which recommend that providers assess for and respond to various social and legal risk factors upon treatment entry.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Work for this article was supported by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations (TPP 62-500), by the VA Special Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center Fellowship Program in Advanced Psychiatry and Psychology, and by the VA Heath Services Research and Development Service (RCS 00-001). The authors thank the Center for Substance Abuse Treatment of the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and research staff and participants in NTIES for producing the data on which this study is based. The views expressed are the authors' and do not necessarily represent the views of the VA.

The authors report no competing interests.