Violence perpetrated by persons with severe mental illness

Incidence. Incidence refers to the number of new cases of a disease that occur during a specifiedperiod of time in a population at risk of developing the disease (

24 ). We could not find any studies that measured the incidence of violence perpetration.

Prevalence. Prevalence refers to the number of affected persons present in the population divided by the number of persons in the population within a given period of time (

24 ).

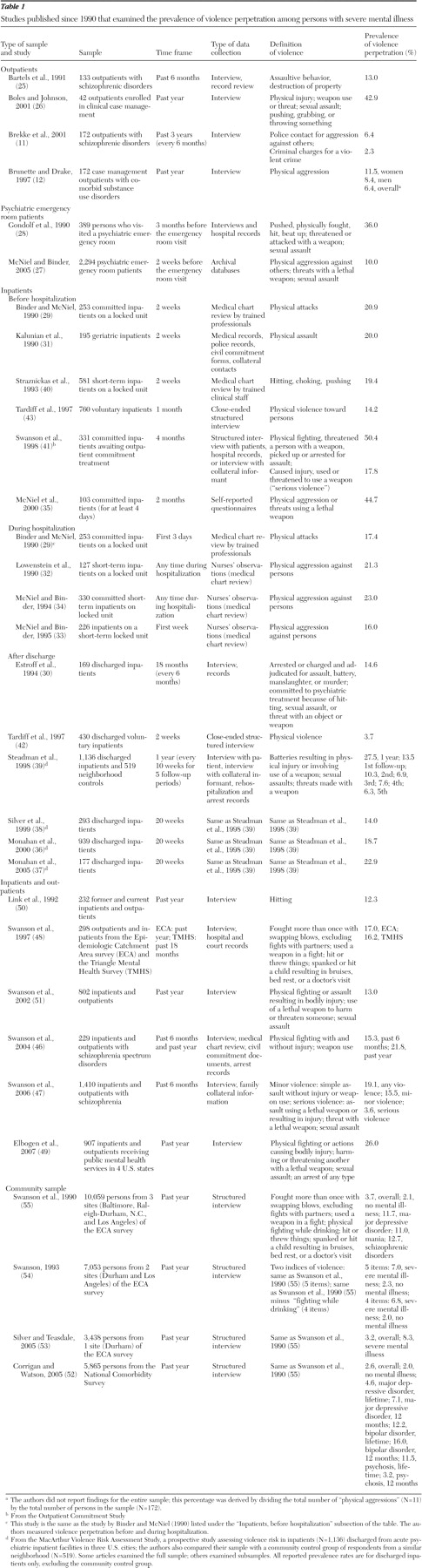

Table 1 lists studies of the prevalence of violence perpetration by the type of sample.

Outpatients. Table 1 lists four studies that examined outpatients (

11,

12,

25,

26 ). One study used a sample that was too small (N=42) to generate reliable prevalence rates (

26 ). Prevalence of violence ranged from 2.3% (

11 ) to 13.0% (

25 ) and varied by time frame (recall period) and type of measure. The rates in the study by Brekke and colleagues (

11 ) were lower than those in the other studies because of Brekke and colleagues' narrow definition of violence—criminal charges for a violent crime in the past three years (2.3%) and contacts with police for aggression against others (6.4%). Conversely, the rates in the study by Bartels and colleagues (

25 ) were higher than those in other studies, most likely because these authors examined self-reported violence among "the most severely disturbed patients" discharged from a state hospital.

Psychiatric emergency room patients. As

Table 1 shows, two studies examined psychiatric emergency room patients. Prevalence of violence ranged from 10.0% in the two weeks before patients' emergency room visits (

27 ) to 36.0% in the previous three months (

28 ). McNiel and Binder's (

27 ) rates may be low because they used mental health records to assess violence instead of self-report. Conversely, Gondolf and colleagues (

28 ), who studied an "accidental" sample (N=389), may have found higher rates because they used both self-reports and hospital records.

Inpatients. Table 1 shows that of the 31 published articles on violence perpetration among persons with severe mental illness, approximately half (48%, or 15 studies) (

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43 ) examined samples composed solely of inpatients. Of these, more than half (53%, or eight studies) (

29,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39,

41 ) included committed inpatients in the sample—four studies examined only committed inpatients (

29,

34,

35,

41 ). Prevalence rates varied widely in these studies, depending on the measure of violence and when the violence took place relative to the hospitalization.

For violence occurring before hospitalization, findings varied by time frame and by type of hospitalization. Prevalence ranged from 14.2% among voluntary inpatients in the month before hospitalization (

43 ) to 50.4% among committed inpatients in the four months before hospitalization (

41 ). The higher rates of violence among committed inpatients than among other inpatients may be the result of the national dangerousness standard used in many states' commitment procedures, in which being "imminently" or "probably" dangerous precipitates hospitalization (

44 ). Overall, the prevalence of violence was highest in studies of committed inpatients, those that used broader definitions of violent behavior (

35,

41 ), and those that measured self-reported violence (

35,

41 ) instead of using medical chart reviews (

29,

40 ) or official records (medical records, police records, or civil commitment forms) (

31 ).

For violence occurring during hospitalization, prevalence rates varied from 16.0% during the first week of hospitalization to 23.0% for violence occurring any time during hospitalization.

Table 1 shows that all four studies of violence during hospitalization examined patients in locked units and assessed violence by using medical chart reviews (

29,

32,

33,

34 ).

For violence after hospitalization, findings varied by type of sample and time frame. The lowest prevalence rates of self-reported "physical violence" (3.7%) were reported within two weeks after discharge by voluntary inpatients (

42 ). The highest rates (27.5%) were reported among inpatients participating in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study during the year after discharge, of whom over two-fifths had been involuntarily committed (

39 ). Involuntary patients were significantly more likely to be violent at follow-up than voluntary patients (

45 ).

Table 1 shows that the prevalence of violence in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study decreased with time. Of note, after the analyses controlled for substance abuse, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of violence between the MacArthur sample of discharged patients and a control group of persons without mental disorders who lived in the community (

39 ).

In summary, studies of inpatients with severe mental illness show that perpetration of violence is most prevalent among committed patients before hospitalization, when violence may have precipitated their commitment. Moreover, prevalence rates were higher in studies that assessed a broad range of self-reported violent acts than in those that relied solely on medical chart reviews.

Studies combining inpatients and outpatients. Six studies combined inpatients and outpatients. All collected self-reported data, and time frames varied from the past six months (

46,

47 ) to the past 18 months (

48 ). Prevalence rates of violence ranged from 12.3% to 26.0% (

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51 ), lower than prevalence rates found in most studies of inpatients and higher than rates found in most studies of outpatients. The highest rate (26.0%), which was reported by Elbogen and colleagues (

49 ), combined self-reported violent behavior and any arrest (violent and nonviolent), which may have inflated the rates in this study.

Community samples. As

Table 1 shows, only four of the 31 articles reported studies in which community samples were examined (

52,

53,

54,

55 ). In the four articles, data were from two multisite community surveys of mental disorders—the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) survey (

53,

54,

55 ) and the National Comorbidity Survey (NCS) (

52 ). Because these surveys were not designed to assess violent behavior, the authors derived a dichotomous variable—any violence (yes or no)—from the sections on mental disorders, physical health, and recent life events.

In studies that used the ECA data (

53,

54,

55 ), the authors used five questions from the Diagnostic Interview Schedule's antisocial personality disorder and alcohol use disorder modules; respondents were scored as violent if they responded positively to one or more items. Items varied in the level of severity assessed from "physical fighting while drinking" to "used weapon in a fight." Among persons with severe mental illness, prevalence of any violent behavior in the past year ranged from 6.8% to 8.3% (

53,

54,

55 )—up to four times higher than among persons who were not diagnosed as having a mental disorder. Swanson and colleagues (

54,

55 ) also examined differences by age, gender, and socioeconomic status in comparisons of persons with major mental disorders and persons without any disorder; however, subsamples were too small to estimate the effect of major mental disorder separately within sociodemographic categories (

56 ).

In the study using NCS data (

52 ), respondents were scored as violent if they reported that they "had serious trouble with the police or the law" or "had been in a physical fight." Analyses focused on differences among diagnostic groups. Prevalence of violence ranged from 4.6% in the past year for persons with a lifetime diagnosis of major depressive disorder to 16.0% for persons with a past-year diagnosis of bipolar disorder; these rates were two to eight times higher than the prevalence among persons without a mental disorder. Findings from this study, however, conflated violent behavior with involvement with the police, which may or may not have been precipitated by violence.

Violent victimization among persons with severe mental illness

Incidence. Most general population studies of crime victimization, such as the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS) (

23 ), examine incidence. To our knowledge, only one study of adults in treatment with severe mental illness investigated the incidence of recent violent victimization (

19 ). Using the same instruments as the NCVS, Teplin and colleagues (

19 ) examined 936 randomly selected persons with severe mental illness from a random sample of treatment facilities—outpatient, day treatment, and residential treatment—in Chicago. There were 168.2 incidents of violent victimization per 1,000 persons per year, more than four times greater than the rate in the general population. Incidence ratios remained statistically significant even after the analysis controlled for sex and race-ethnicity.

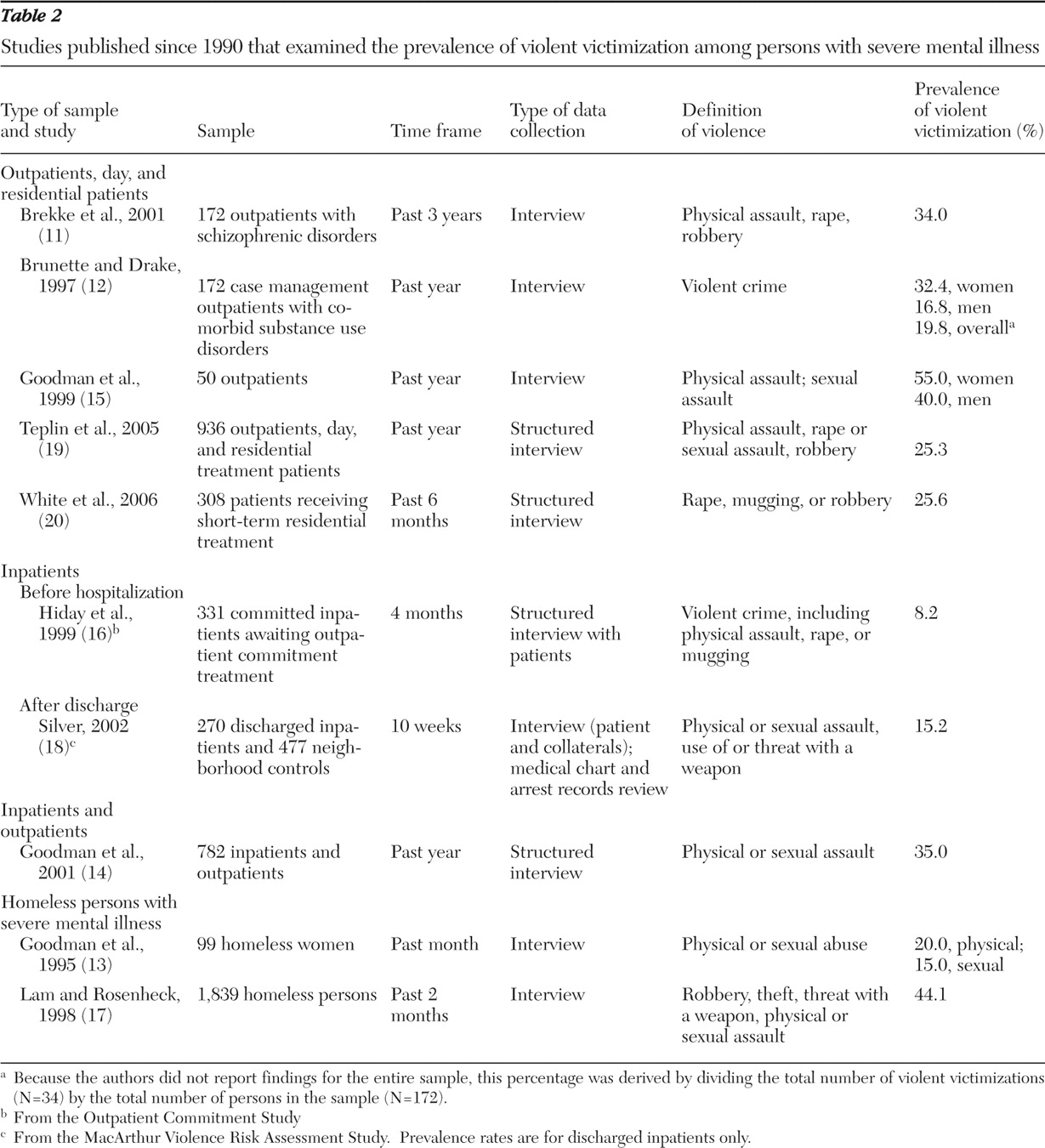

Prevalence. Table 2 shows that all ten studies examined self-reported prevalence of victimization. Prevalence varied because of differences in sample sizes, time frames, and type of sample. One study had too small a sample to generate reliable prevalence rates of relatively uncommon events such as violent victimization (

15 ). Studies of treatment populations with larger samples (N≥100) found prevalence rates of recent violent victimization between 8.2% in the past four months (

16 ) and 35.0% in the past year (

14 ). The largest study of homeless persons with severe mental illness found that 44.0% had been violently victimized in the past two months (

17 ). Among studies that assessed violent victimization in the past year—the same time frame as the NCVS—prevalence rates ranged from 25.3% (

19 ) to 35.0% (

14 ), compared with 2.9% in the NCVS.

Prevalence rates appear to vary by type of victimization. However, these differences may be attributable to the way that victimization was measured. For example, White and colleagues (

20 ) asked only one question about victimization in the past six months. Other studies collected detailed information on the type of victimization (

13,

14,

17,

19 ).

Prevalence rates also varied by the type of sample. For example, 19.0% of the sample of outpatients and patients in residential treatment in the study by Teplin and colleagues (

19 ) and 35.0% of the combined sample of inpatients and outpatients in the study by Goodman and colleagues (

14 ) had been victims of physical assault in the past year. Similarly, prevalence of rape and sexual assault in the past year ranged from 2.6% among outpatients (

19 ) to 12.7% in a combined sample of outpatients and inpatients (

14 ). Prevalence of victimization among homeless persons with severe mental illness was generally higher than in treatment samples (

13,

17 ). Irrespective of the type of sample and type of victimization, prevalence was much higher in all studies listed in

Table 2 than in the general population, as found in the NCVS (

23 ).

Comparing perpetration of violence and violent victimization

Are persons with severe mental illness more likely to be perpetrators of violence or victims of violence?

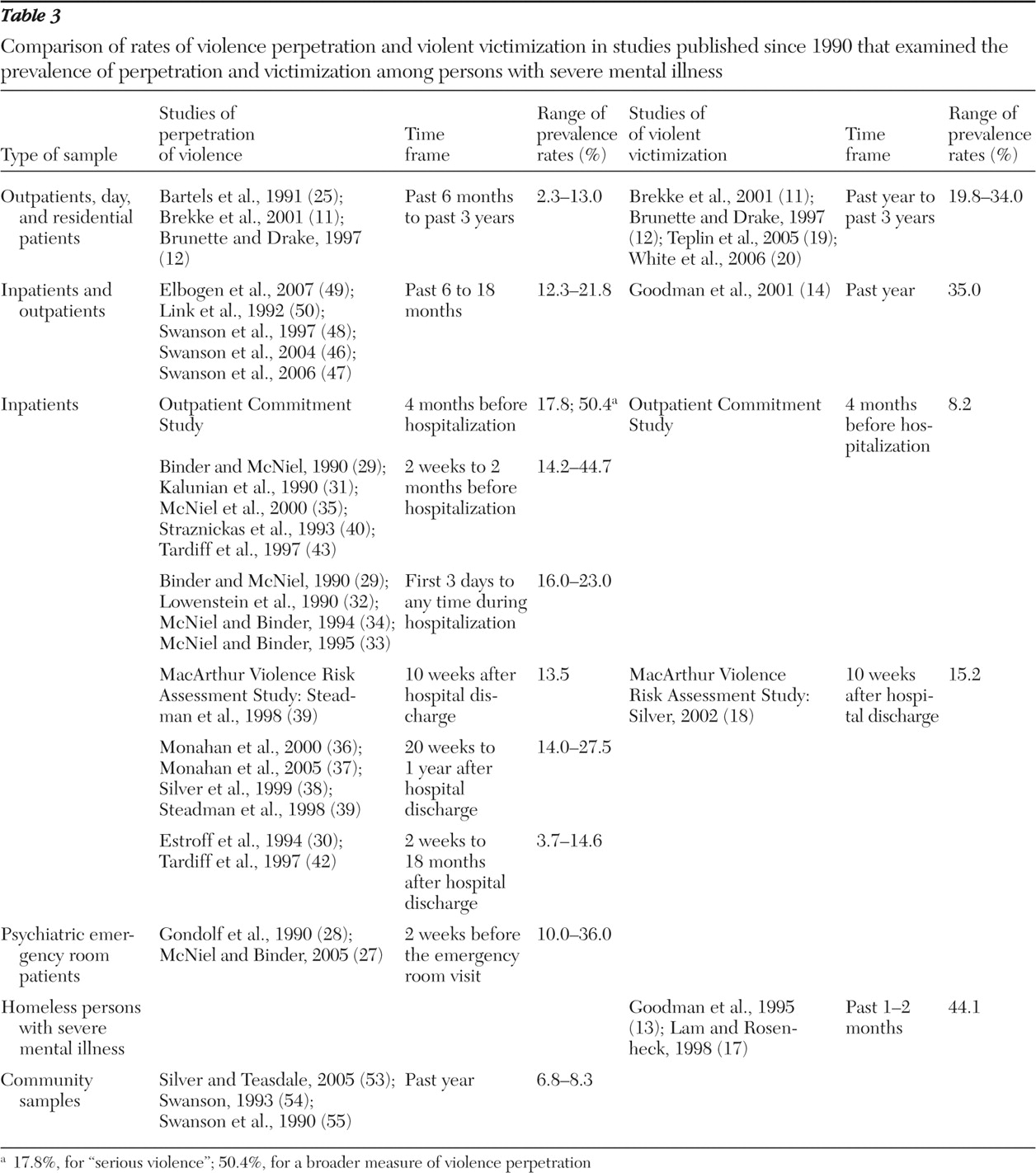

Table 3 summarizes and compares the prevalence of violence perpetration and violent victimization from the studies in

Table 1 and

Table 2 .

Only three studies assessed perpetration and victimization among the same participants. Brekke and colleagues (

11 ) found that among outpatients with schizophrenic disorders, 6.4% had contact with police for "aggression against others" in the past three years and 34.0% reported being violently victimized. The marked differences in rates may be attributable to the fact that violence perpetration was counted only if the person had contact with the criminal justice system; many violent behaviors do not come to the attention of the police or culminate in formal processing (

57 ). Had the authors used a broader measure of violence, the reported differences between perpetration of violence and violent victimization might have been less dramatic. A study by Brunette and Drake (

12 ) had similar findings; 6.4% of their sample had been physically aggressive in the past year, and 19.8% had been a victim of a violent crime in the past year. In the Outpatient Commitment Study, Swanson and colleagues (

41 ) found that among committed inpatients, the prevalence of violence perpetration in the four months before commitment ranged from 17.8% for "serious violence" to 50.4% for a broader measure of violence; in contrast, 8.2% reported violent victimization (

16 ).

Why was the prevalence of perpetration of violence so high in the Outpatient Commitment Study? Most likely, it was because participants were sampled soon after commitment. The authors did not indicate the proportion of individuals in the sample who were committed because of their violent behavior. The discrepancies between violence perpetration and violent victimization may also have resulted from differences in the definitions of violence. Victimization was narrowly defined as self-reported "violent crimes"; perpetration of violence referred to a range of violent behaviors elicited from patients and their collaterals as well as from hospital records.

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study provided some information about violence perpetration and violent victimization among discharged inpatients. The authors reported that 13.5% of the sample had perpetrated violence (

39 ) and 15.2% had been victims (

18 ) ten weeks after discharge from a psychiatric inpatient unit. However, because one report used a subsample (

18 ), rates are not directly comparable.

Other studies listed in

Table 3 show that irrespective of the type of sample and regardless of the time frame, violent victimization is more prevalent than violence perpetration. For example, among outpatients and residential patients with severe mental illness, 20.0% to 34.0%, depending on the time frame and gender, had been a victim of recent violence (

11,

12,

19,

20 ), compared with 2.0% to 13.0% who had perpetrated violence (

11,

12,

25 ). Similarly, in samples that combined outpatients and inpatients, 35.0% reported violent victimization in the past year (

14 ), compared with 12.0% to 22.0% who had perpetrated violence (depending on whether the time frame was 12 or 18 months and who reported recent perpetration of violence) (

46,

47,

48,

49,

50 ).