During the past ten years, several drug manufacturers introduced second-generation antipsychotic agents for the treatment of severe mental illnesses, including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Advantages over older agents include a reduction in some major side effects, such as tardive dyskinesia, and possibly improved adherence by patients to treatment (

1,

2 ). Conversely, there has been extensive debate over the impact of second-generation agents on other adverse outcomes, such as incidence of diabetes and weight gain, and the cost-effectiveness of second-generation agents versus the older antipsychotic agents (

2,

3,

4 ). Acquisition costs of second-generation antipsychotic medications are much higher than for older treatments (

4 ). Medicaid programs are especially vulnerable to this cost because they have historically paid for approximately 75% of antipsychotic expenditures (

4 ). In 2003 three of the four highest-cost medications in Medicaid nationwide were second-generation antipsychotic agents (olanzapine, risperidone, and ziprasidone) (

5 ). Because overall Medicaid drug expenditures grew at an average of 15.4% annually from 1994 to 2004, many states have introduced measures to reduce drug expenditures (

6 ).

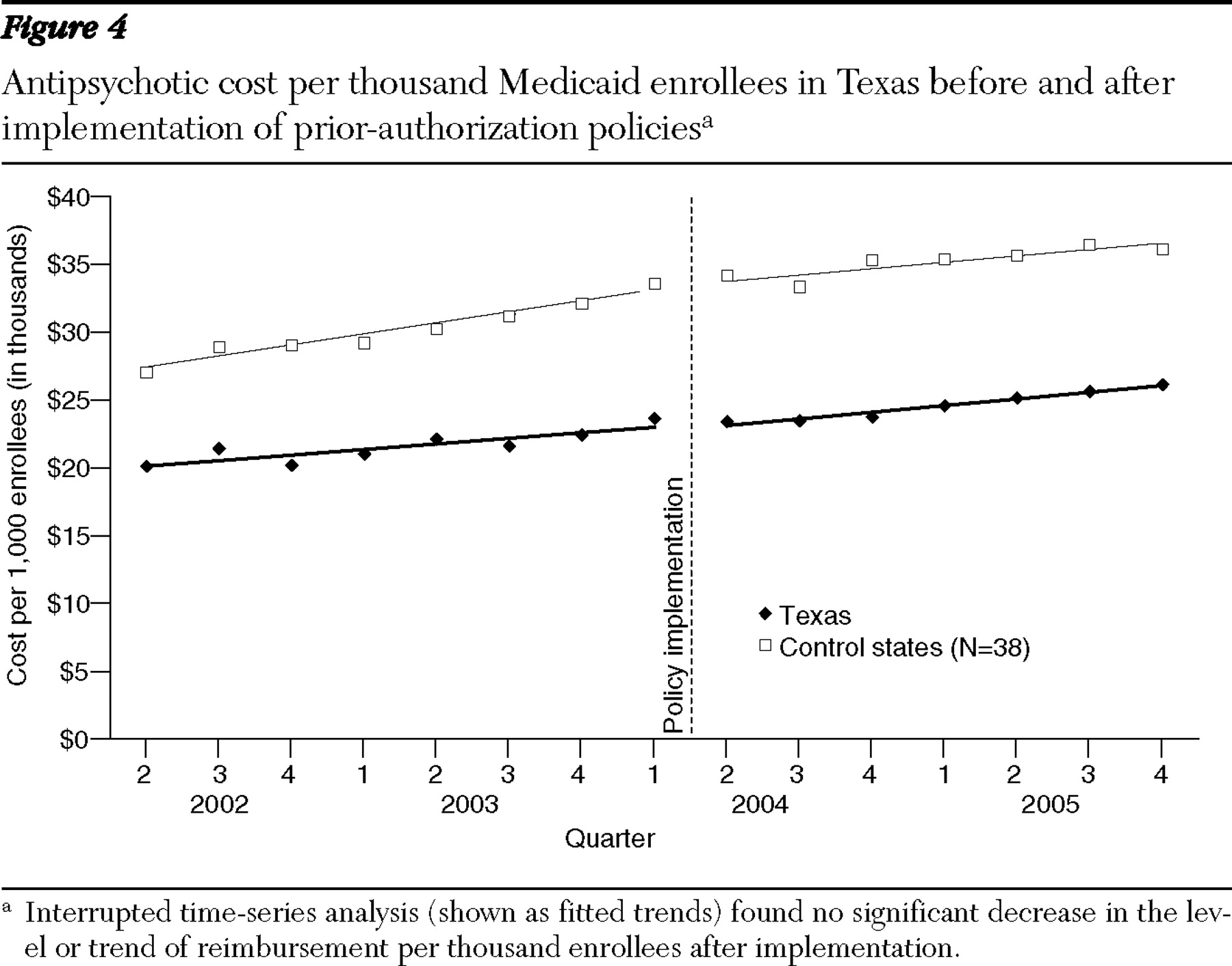

Medicaid programs must cover all drugs from manufacturers that have rebate agreements with the federal government. Thus their ability to exclude specific drugs from coverage is limited (

7 ). However, states can impose requirements such as prior authorization and step-therapy protocols, which require failure of one or more preferred medications before coverage is provided for nonpreferred agents (

8 ). Prior-authorization policies potentially reduce costs in two ways (

9 ). First, they allow states to list lower-cost or lower-risk medicines as "preferred" (not requiring prior authorization), saving on per-prescription pharmacy costs, which we investigated in this study. Second, states may negotiate supplemental rebates with manufacturers in return for preferential listing. However, depending on the drug class in question, prior-authorization policies might also have significant unintended consequences, including substantial burden on provider and patient time, increased treatment discontinuities, and reduced quality of care.

Studies of other medication classes demonstrate large decreases in pharmacy costs after implementation of prior-authorization policies. Smalley and colleagues (

8 ) found that pharmacy costs for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents dropped by 65% in Tennessee Medicaid after a prior-authorization requirement was established for nongeneric medications. Similarly, a prior-authorization requirement for proton pump inhibitors implemented in Georgia's Medicaid program reduced drug expenditures by one-third (

10 ). Both studies also found no cost increases for other health care services. Finally, Medicaid prior-authorization policies for Cox-2 inhibitors decreased pharmacy costs per prescription by 18% (

11,

12 ). However, all of these policies affected drug classes used primarily for treating symptomatic conditions with low-cost alternative therapies. Because all major second-generation antipsychotic agents remain under patent protection and treat severe mental illnesses, potential savings may differ markedly.

Many Medicaid programs prohibit restrictions on second-generation antipsychotic agents because of the severity of chronic mental illness (

7,

13 ). In 2003 a total of 26 states explicitly exempted second-generation antipsychotic agents from prior authorization (

14 ). Recently, however, at least ten other Medicaid programs have instituted prior-authorization requirements for particular second-generation antipsychotic agents (specifically, aripiprazole), and 22 require prior authorization for particular dosing forms (such as long-acting injec risperidone) (

15 ). Further, nearly one-third of Medicare Part D plans restrict particular second-generation antipsychotic agents (

16 ). Research indicates that a prior-authorization policy in Maine increased the rate of discontinuities in antipsychotic treatment but had no discernible impact on pharmacy costs (

17 ). Because this finding runs counter to prior research on different medication classes cited earlier, and because Maine rescinded its policy after only eight months, we examined data from two other states to determine whether the expenditure results are consistent in states with policies of longer duration.

Discussion

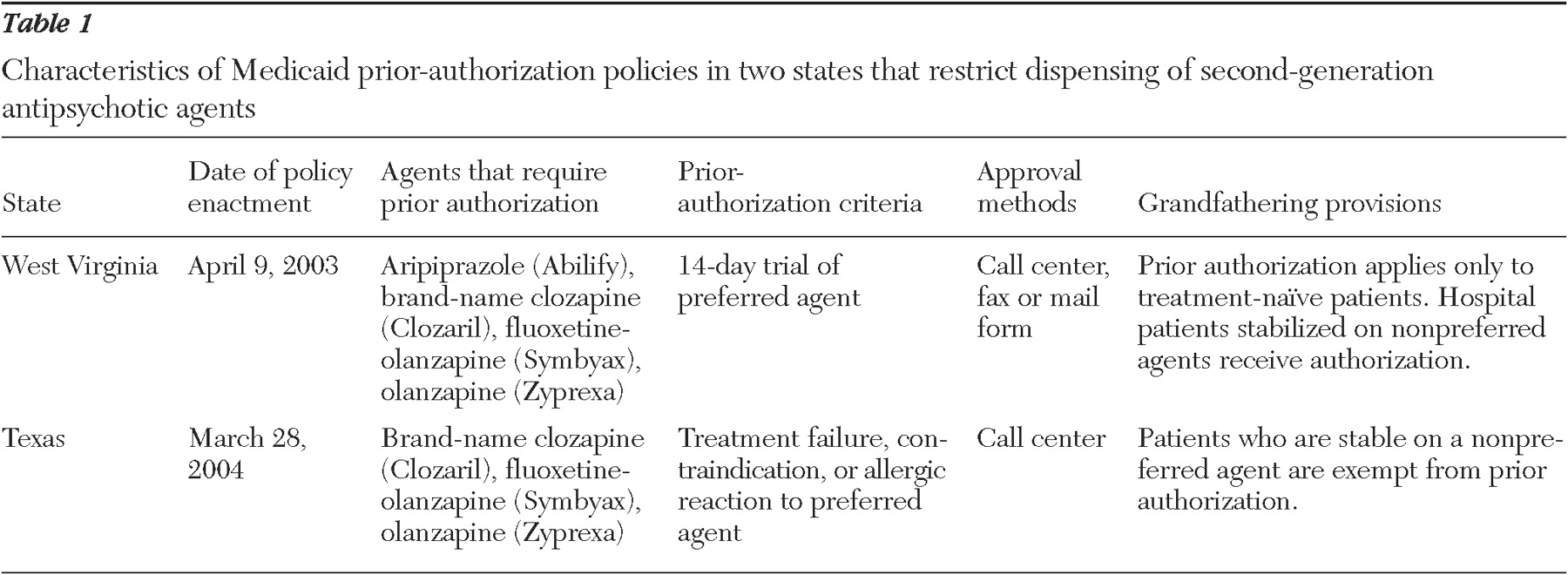

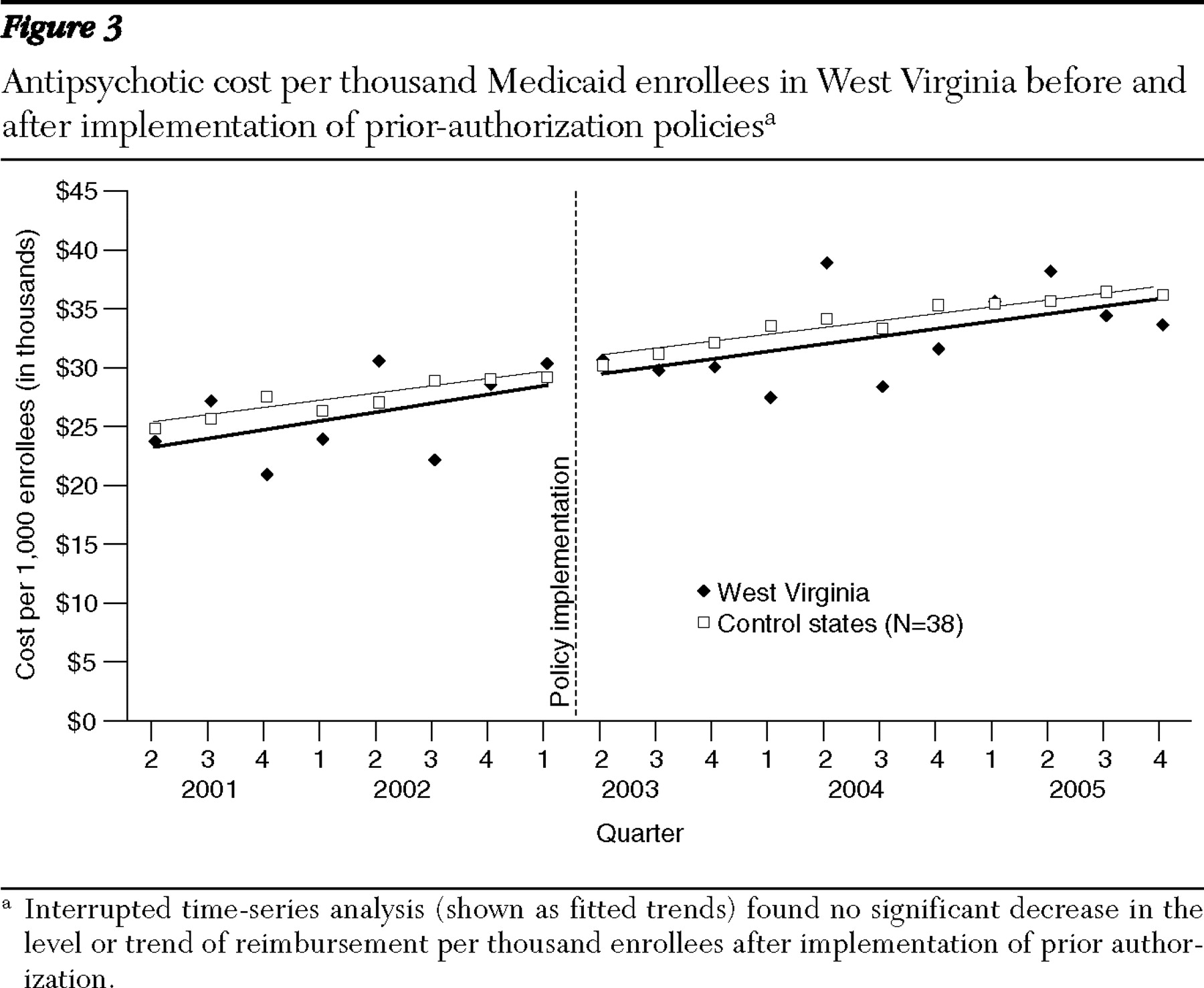

The results of this study indicate that even though prior-authorization policies for second-generation antipsychotics caused significant shifts in market share, their impact on pharmacy reimbursement was minimal. These observations are consistent with previously reported results from Maine, which used patient-level claims data (

17 ). However, these results contrast sharply with past studies in the literature on prior-authorization programs, where, with similar methods, major reductions in reimbursement were demonstrated across several medication classes (

8,

10,

1 1).

The observed differences could result from the way prior-authorization policies were implemented, the nature of psychotropic medications for severe mental illness, or characteristics of the alternative medications available in this class (

26 ). First, there were extensive grandfathering provisions for individuals who were already receiving antipsychotics. Second, because clinical guidelines suggest long-term treatment with antipsychotics, the number of newly treated patients who are subject to prior authorization represents a smaller proportion of the total patient population than for other medicines (

13 ). Finally, clinicians may be more willing to seek prior authorization for patients with severe mental illnesses, because antipsychotic agents may be considered less therapeutically substitu than other classes as a result of heterogeneous patient response (

27 ). However, our market share analysis showed that prior authorization shifted utilization toward preferred agents, indicating that the above factors are not preventing all changes in the medications that patients are receiving.

Alternatively, the lack of change in pharmacy reimbursement could result from the absence of lower-cost generic alternatives among second-generation antipsychotics. Essentially, the prior-authorization policies steer utilization toward drugs with similar reimbursement levels. This is comparable to results from a study of prior authorization for angiotensin receptor blockers, which found little impact on reimbursement (

28 ). Moreover, clinicians may respond to prior-authorization policies by increasing the dose of less optimal medications or increasing use of multiple antipsychotics (polypharmacy), both of which would reduce any savings. Unfortunately, we could not test these hypotheses with our aggregate state-level data set. This difference in reimbursements may change in 2008, when risperidone is scheduled to lose patent protection, or in 2011, when olanzapine follows (

29 ). Although cost levels were lower in Texas in both pre- and postpolicy periods, this probably results from a long-standing three-drug cap for Medicaid recipients (

30 ).

Although this study examined reimbursements to pharmacies as the major outcome, there are at least three other costs that might change because of prior-authorization policies. First is the cost of administering such programs. Administration of the Texas preferred drug list program, for example, cost $4.4 million in fiscal year 2005 for all drug classes (

31 ). Second, considerable physician, pharmacist, and patient time are required to comply with prior-authorization policies. Administrative restrictions in both Medicaid and Medicare Part D are estimated to place substantial financial and time burdens on clinicians (

32,

33 ). Finally, the policies may have unintended consequences on utilization of hospital and physician services. Our previous patient-level analyses in Maine suggested that the Medicaid prior-authorization policy for second-generation antipsychotic agents led to an increase in treatment discontinuities, including gaps, switching, and augmentation of therapy. Because such gaps in adherence are associated with higher health care costs, there may be clinical implications of prior authorization for antipsychotic medications (

34 ).

In addition to these unmeasured costs, pharmacy reimbursement data do not include supplemental rebates obtained by Medicaid programs for listing specific agents as preferred drugs (

35 ). These were likely a primary rationale for implementing prior-authorization policies in the 37 states that have such agreements, but the sizes of rebates remain confidential (

36 ). The Texas Medicaid program reports that implementation of its preferred drug list and prior-authorization program resulted in drug savings from supplemental rebates of approximately 5% during fiscal years 2004 and 2005 (

31 ). If data on rebates were available for inclusion in our analysis, these states likely would have realized a small net drug savings from the policies. However, the advent of Medicare Part D will likely reduce potential savings from rebates. Because private-sector Part D plans now cover all dually eligible Medicaid recipients, states will lose significant purchasing leverage and will likely receive lower rebates given the smaller market size of the plans. Texas, for example, estimates that rebates will be 37.5% lower in fiscal year 2007 than they would be if Part D were not in place (

31 ). Although Part D plans reduced the absolute Medicaid expenditure on antipsychotics, this class of drugs is likely to remain among the most expensive.

These findings have significant implications for Medicare Part D plans as well. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid determined that second-generation antipsychotic agents are a protected class, meaning that plans must cover at least one form of each drug in the class. However, plans can require prior authorization for newly treated patients, similar to Medicaid requirements. Part D plans vary significantly in their coverage of second-generation antipsychotic agents; each of the second-generation medications was subject to prior authorization in 8% to 28% of Medicare drug plans (

16 ). This situation is likely to be confusing for providers and patients, who face many different plan restrictions, rather than the single list in Medicaid programs (

37 ). Moreover, Part D plans have thus far been less successful than Medicaid programs at negotiating rebates. In 2007 Part D plans achieved 8.1% in drug savings through rebates, only one-third of the 26% saved in Medicaid (

38 ). As a result, all manufacturers of second-generation antipsychotic agents noted significant revenue increases after the shift of dually eligible individuals to Part D (

39 ). Thus potential rebate savings from prior authorization may be lower in some of these plans than can be realized in Medicaid programs.

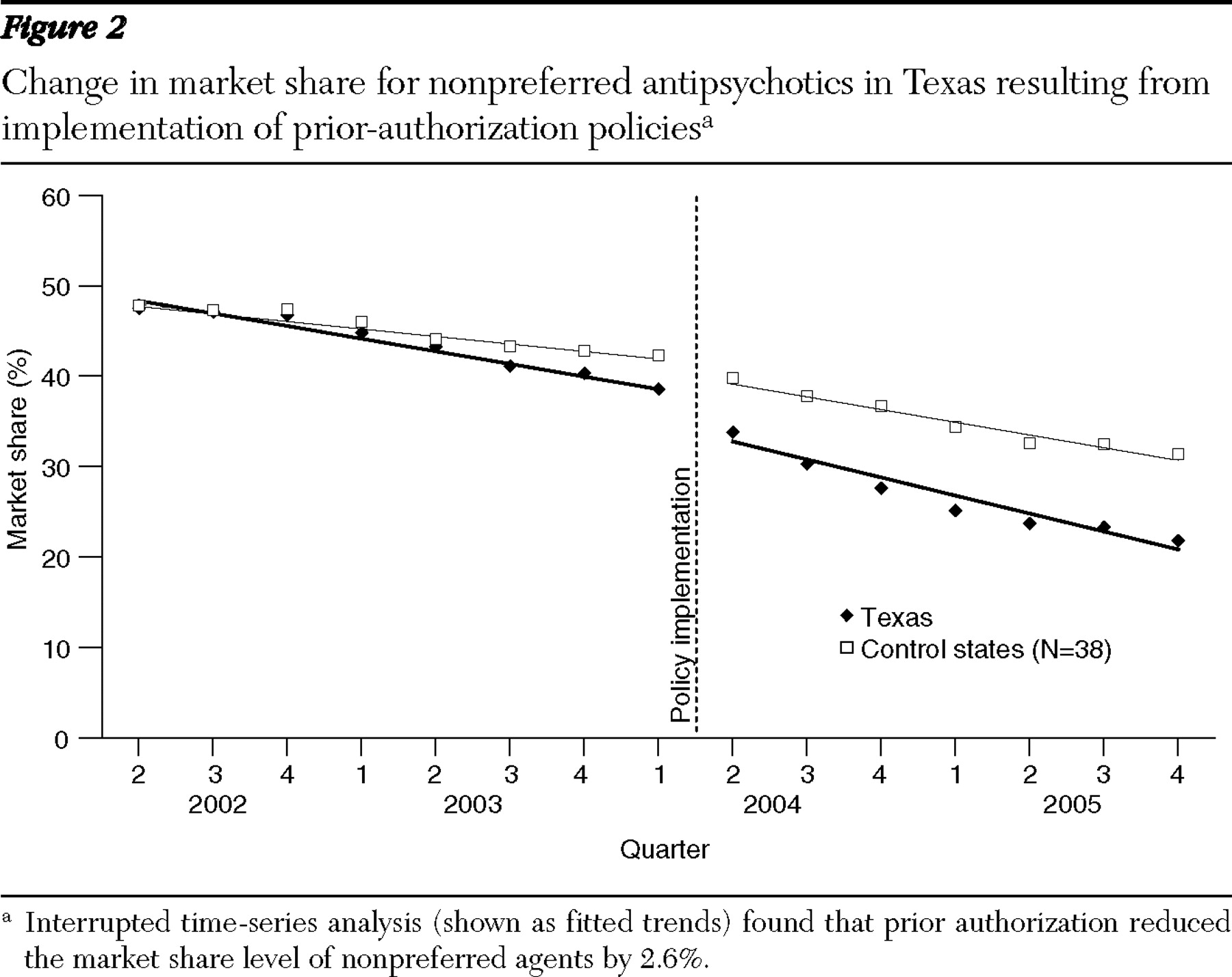

We acknowledge the limitations of our analysis. First, we have some concerns about the data for total reimbursement in West Virginia.

Figure 3 shows that despite a consistent trend, reported reimbursements varied significantly between quarters. Whether this is a product of inconsistent reporting or of the way in which pharmacy reimbursement occurs in the state is unclear. Nonetheless, the fitted trend was s over time. Second, the prior-authorization policies in Texas and West Virginia may not be representative of the experience in other states and may differ in their authorization criteria, drugs covered, and implementation. However, given the broad geographic dispersion and differing population sizes, we feel that the consistency of results is important. Moreover, the drugs typically subject to prior authorization in other state programs are similar to those in the study states.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Mr. Law is supported by the Fellowship in Pharmaceutical Policy Research at Harvard Medical School and a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada doctoral fellowship. Dr. Ross-Degnan and Dr. Soumerai are investigators in the HMO Research Network Centers for Education and Research in Therapeutics, supported by grant U18-HS-010391 from the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The authors thank Alyce Adams, Ph.D., Daniel Ball, Dr.P.H., Michael Fischer, M.D., M.S., Haiden Huskamp, Ph.D., Jennifer Polinski, M.P.H., M.S., and Katherine Swartz, Ph.D., for valuable assistance.

Dr. Ross-Degnan and Dr. Soumerai report research funding of a separate study on the effects of prior authorization for second-generation antipsychotic agents from a public-private partnership program supported by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Eli Lilly and Company, and the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Foundation. Mr. Law reports no competing interests.