Tobacco smoking is the leading preventable cause of death and disease in Australia (

1,

2 ). Even though the prevalence of smoking has decreased to 20% in the general population (

3 ), high prevalence rates remain for people with psychiatric disorders—32% in community surveys (

4 ), 41%–74% in outpatient services (

5,

6 ), and 70%–90% in inpatient psychiatric units (

7,

8,

9 ). As a consequence, mortality and morbidity resulting from smoking-related diseases are much higher for people with mental illness than for the general population (

9,

10 ).

Traditionally, psychiatric services have often reinforced tobacco smoking through use of smoking as a tool to modify behavior (

11,

12,

13 ) and for rapport building (

13,

14 ). The need for psychiatric services to reorient policies and procedures and provide treatments to address smoking has been strongly argued (

9,

12,

15,

16 ). Large proportions of psychiatric patients report having contemplated a quit attempt (

13,

17 ). An accumulating number of studies have provided insight into the nature of cessation support that may be required for this population, taking into account factors such as a high level of nicotine dependence, concurrent substance abuse, and prescribed psychotropic medications (

18,

19 ).

Not only is it important to provide treatment for smoking to both psychiatric patients and persons in the general population (

1,

2 ) and to address the poorer physical health of psychiatric patients (

10 ), but it is also the duty of health services to protect nonsmoking staff, patients, and visitors from the effects of second-hand smoke. The duty to protect nonsmokers has become a driving force for change in smoking policies and practices in health care settings (

12,

15,

16,

20,

21,

22 ). Research suggests that smoking bans in psychiatric services are accepted by a majority of patients (

23,

24,

25 ). Smoking bans appear to be more successful when consistently applied (

23,

24,

25 ) and when implemented as total rather than partial bans (

23,

25,

26 ). It has also been found that in workplaces (

27 ) and health care settings generally (

28 ), a smoke-free environment is supportive of and conducive to smoking cessation or reduction in consumption by both staff and patients (

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29 ).

In Australia no published research has described smoking policies and smoking care procedures in inpatient psychiatric units, and limited research has been conducted elsewhere (

30 ). In the state of New South Wales (population approximately seven million), the Smoke Free Workplace Policy (

20 ) has been introduced in stages since 1999. In 2005 a directive was issued for all health services to move to full implementation (

31 ). Guidelines for the management of nicotine-dependent inpatients were made available in 2002 by the New South Wales Health Department (

32 ). The guidelines integrate five steps into routine care: identification of smoking status, provision of support for inpatient abstinence, provision of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT), monitoring of withdrawal symptoms, and including a treatment summary in the discharge plan. Although the extent of adoption of these guidelines has been evaluated in general hospital settings (

33 ), the extent in psychiatric services remains unknown. This study was undertaken to identify policies and procedures in public psychiatric inpatient units in New South Wales, smoking care provided in such units, and policies and procedures associated with assessment of smoking status and provision of smoking care.

Methods

Design, setting, and participants

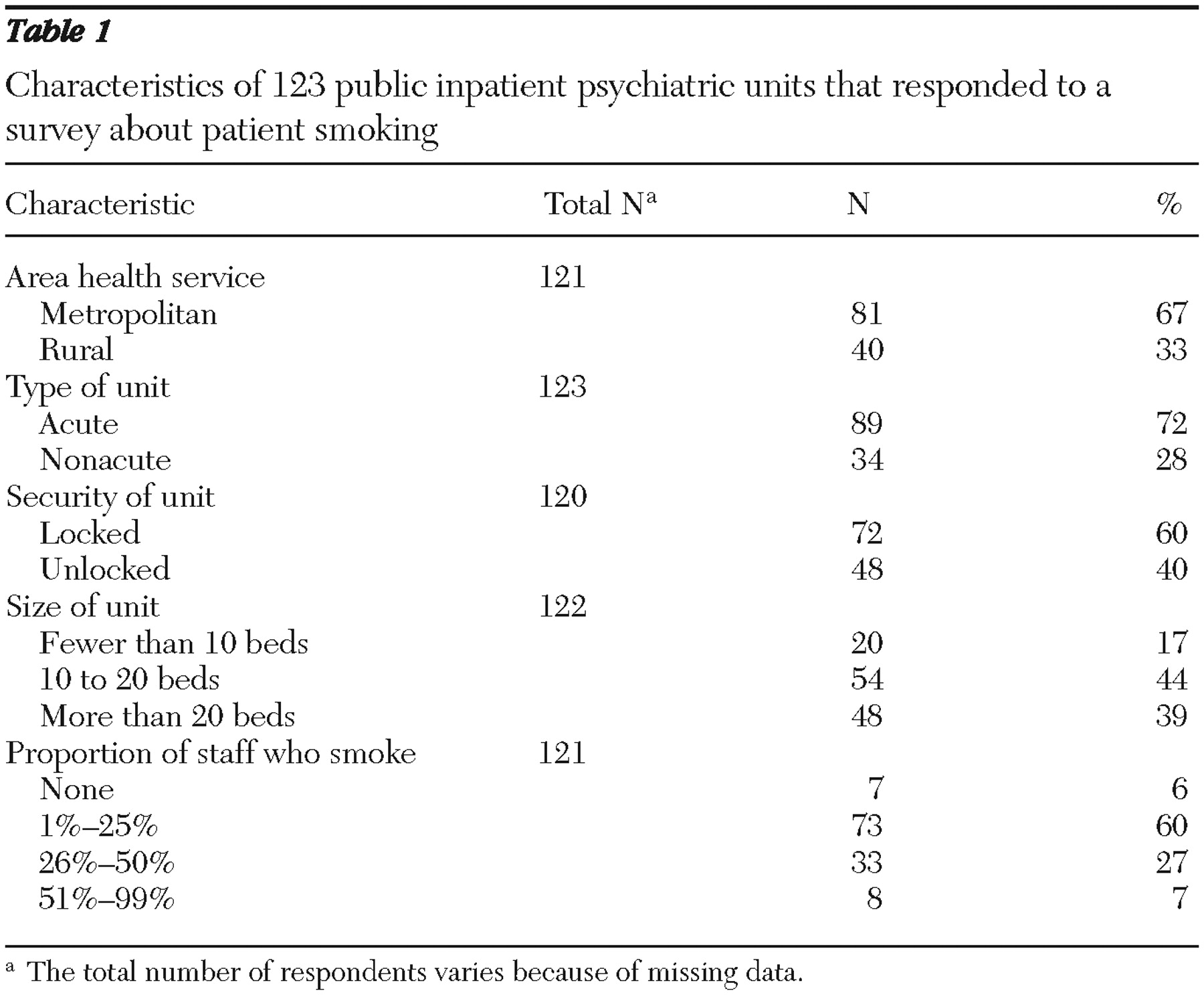

A cross-sectional survey was undertaken in 2006 of all publicly funded psychiatric inpatient units in New South Wales. A list of public psychiatric inpatient units (N=131) was obtained from the New South Wales Health Department, across eight area health services in the state, four metropolitan and four nonmetropolitan.

Procedure

A survey was developed from questionnaires previously used to assess provision of smoking care in Australian drug treatment agencies (

34 ) and the New South Wales guidelines for management of inpatients dependent on nicotine (

32 ). Questionnaires mailed to the nurse unit manager of each psychiatric inpatient unit by the New South Wales chief health officer requested that he or she complete the survey on behalf of the unit. Completed questionnaires were returned to the Health Department, and department personnel followed up with units that did not respond within one month.

Measures

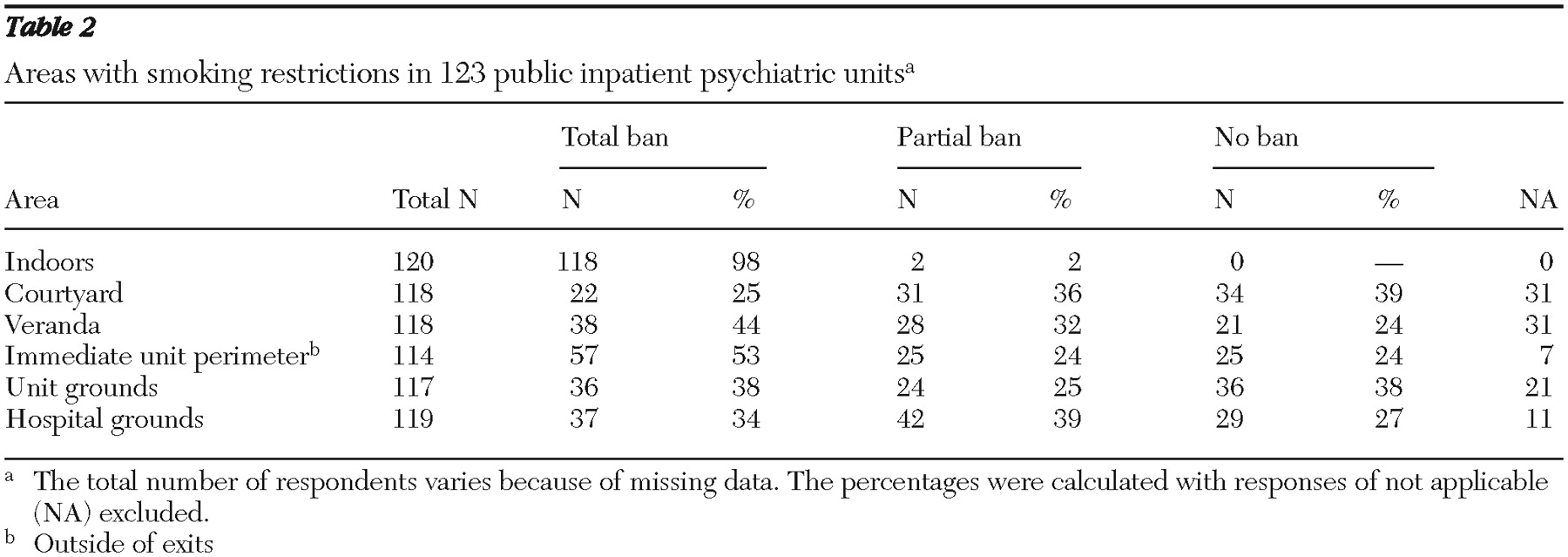

Smoking restrictions. Six questions addressed smoking restrictions for staff and patients. Two yes-no questions assessed the existence of documented smoking policies and smoke detectors in bathrooms and toilets.

Management of staff smoking issues. Four yes-no questions addressed staff smoking practices, adherence to smoking policies, provision of NRT to staff, and occurrence of staff complaints regarding exposure to tobacco smoke.

Smoking care support procedures. Seven questions (yes, no, or unsure) were related to the provision of formal training in smoking assessment and smoking care, the recording of smoking assessment and care, staff discretion regarding smoking assessment and care, and the availability of smoking care guidelines.

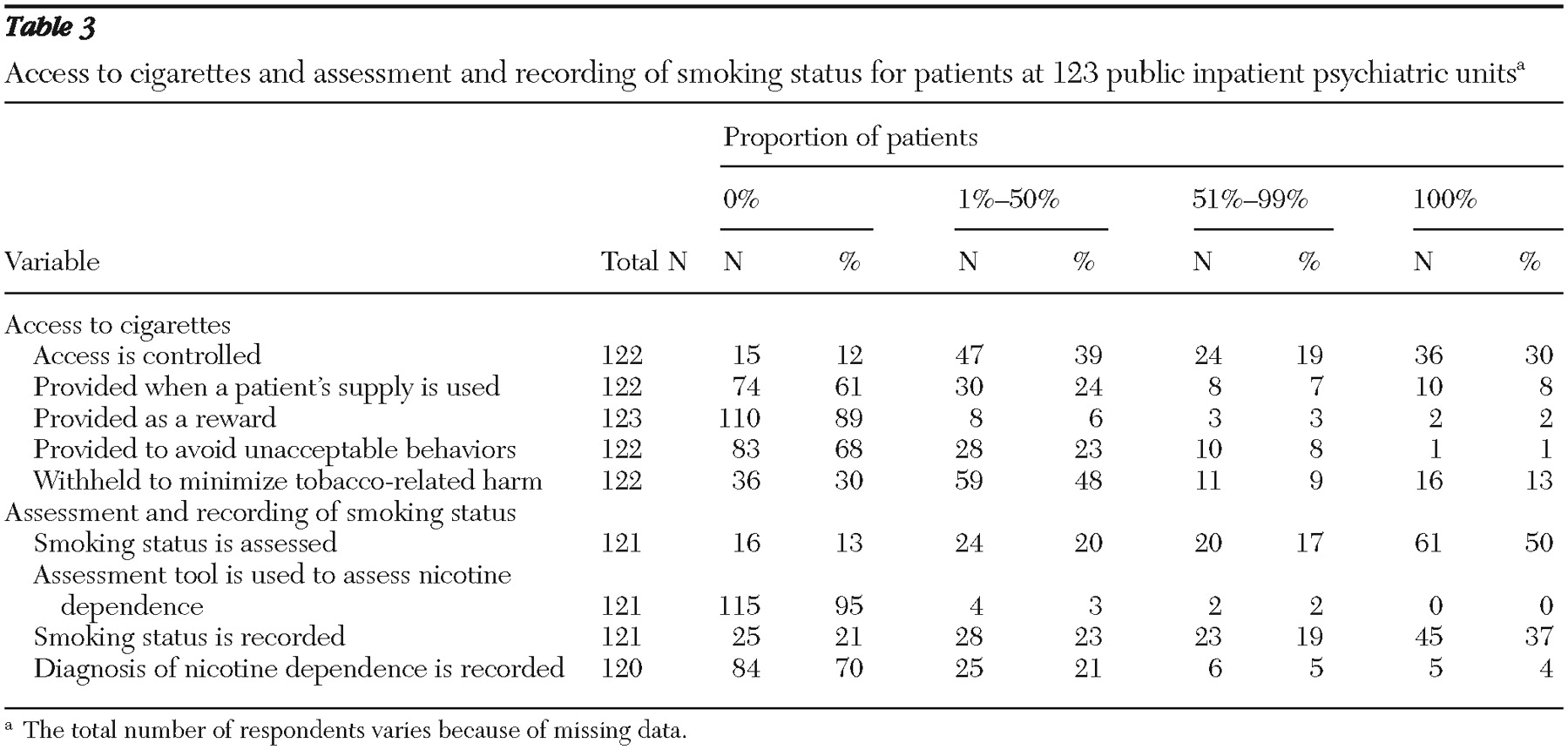

Management of patients' access to cigarettes. One yes-no question assessed whether any patients had begun to smoke during their stay. Five questions assessed the proportion of patients whose access to cigarettes was managed either by providing or withholding cigarettes (0%, 1%–25%, 26%–50%, 51%–75%, 76%–99%, and 100%).

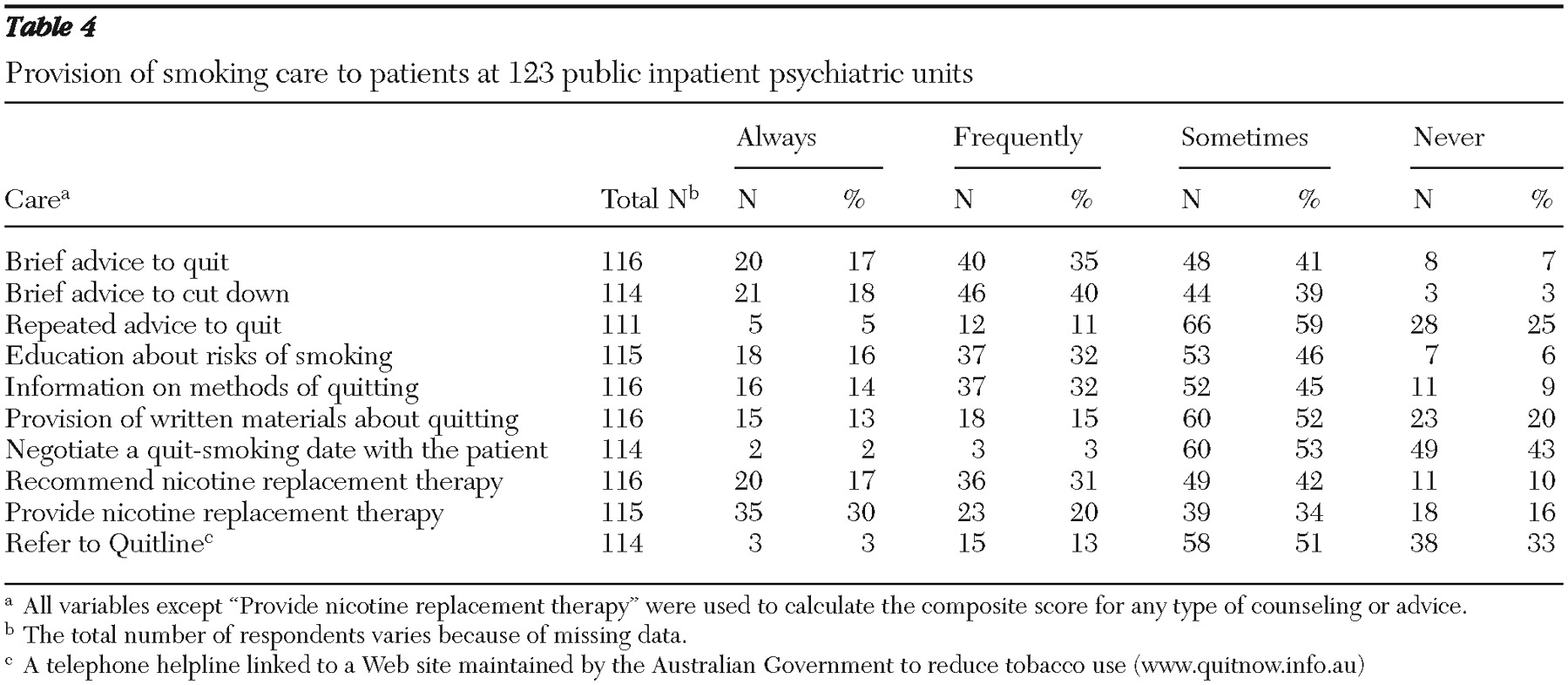

Provision of smoking care: assessment, recording, and cessation interventions. Four questions addressed the proportion of smokers whose smoking status was assessed and recorded, and ten questions measured the proportion of smokers who received smoking care (0%, 1%–25%, 26%–50%, 51%–75%, 76%–99%, and 100%). Nicotine dependence could be determined from information about smoking obtained during patient assessment or by use of a formal assessment tool. Respondents were asked to indicate the frequency with which such care was provided (always, frequently, sometimes, or never). Three questions assessed whether changes in assessment, recording the assessment, or provision of smoking care in the previous 12 months had occurred (increased a lot, increased a little, no change, decreased a little, decreased a lot, or don't know).

Characteristics of the unit and nurse unit manager. Respondents were required to classify their unit as being acute or nonacute and locked or not locked, to describe the unit size in terms of number of beds, and to estimate the percentage of nursing staff who smoked (0%, 1%–25%, 26%–50%, 51%–75%, 76%–99%, and 100%). Respondents indicated their job title, length of time in that position, current smoking status, whether they were responsible for enforcing smoking policies, whether they had had training in smoking interventions, and whether they were interested in receiving training.

Analyses

All analyses were undertaken with SAS version 8.2 (

35 ). Descriptive statistics were used to report the characteristics of participating units and the prevalence of policies and procedures. Response categories for the proportion of patients whose access to cigarettes was managed and to whom smoking assessment and care was provided were collapsed from six to four (0%, 1%–50%, 51%–99%, and 100%).

Possible associations of policies and procedures both with assessment of smoking status and with provision of smoking care were investigated by using chi square analyses (checking for multicolinearity) and stepwise logistic regression, in which variables with a p value of <.25 in the chi square analyses were included. For these analyses, a composite variable score (

36 ) describing the provision of smoking care was constructed for each unit. The composite variable score (maximum score of 6) was calculated by summing three subcomponents: the percentage of patients who had their smoking status assessed (a score of 2 was given if 100% of patients had their smoking status assessed, 1 if the proportion was 51%–99%, and 0 if the proportion was 50% or less). In calculating the score for the second subcomponent—any type of counseling or advice—nine items were included. A score of 2 was given when any of the nine counseling or advice items were reported as always being provided, 1 if any were frequently provided, and 0 if they were sometimes or never provided. In calculating the score for the third subcomponent—frequency of provision of NRT to patients—a score of 2 was given if NRT was always provided, 1 if it was frequently provided, and 0 if it was sometimes or never provided. The composite variable scores were collapsed into dichotomous categories: a smoking care score of 5 or more, which represented the provision of comprehensive smoking care, versus a score of 4 or lower.

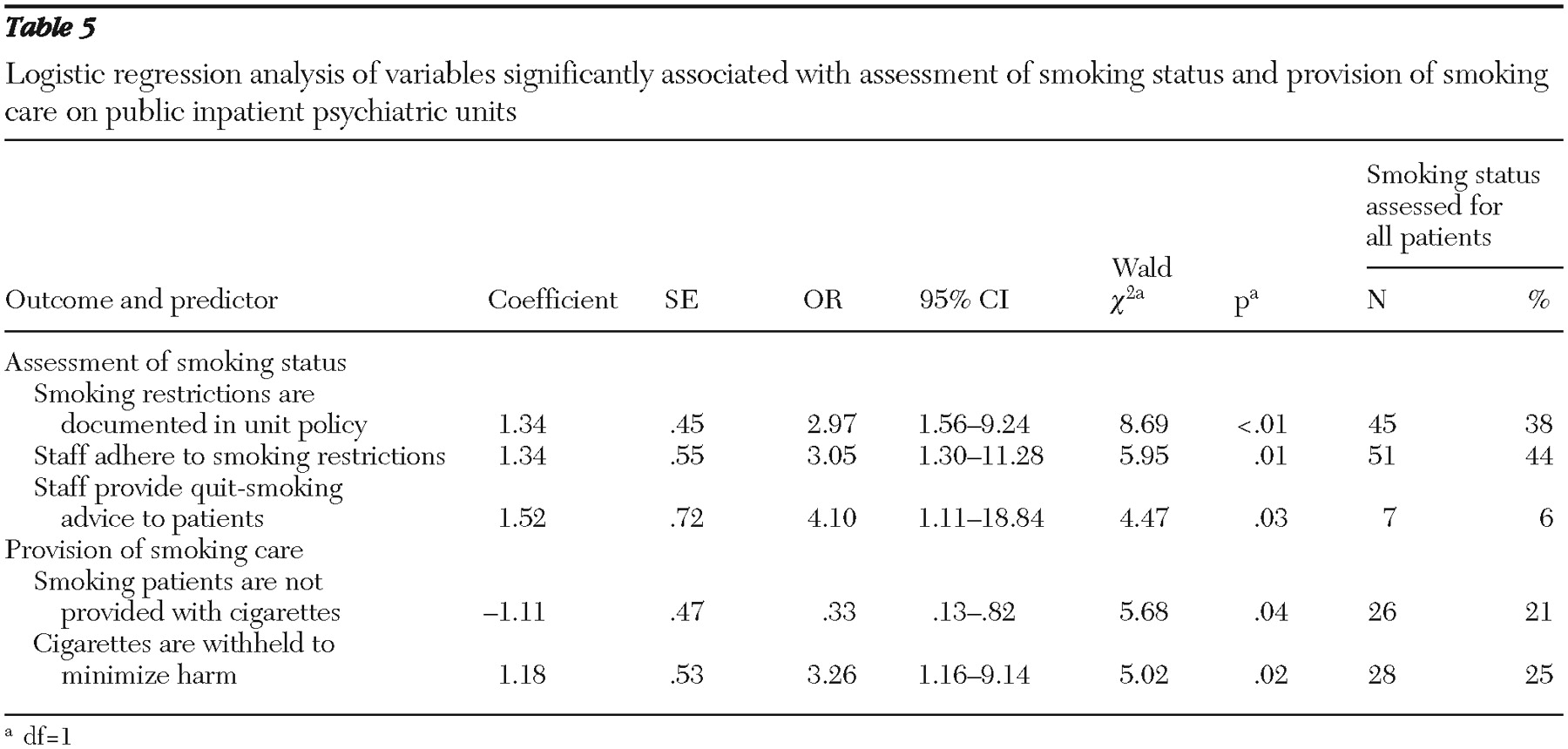

To predict assessment of smoking status, 11 characteristics of the unit and the nurse unit manager and of policies and procedures (all with p values of <.25 in the chi square analyses) were entered into a logistic regression model. The variables were size of unit, proportion of staff smokers less than 25%, documentation of smoking restrictions, enforcement of smoking restrictions, withholding of cigarettes from patients who smoke in order to minimize tobacco-related harm, provision of information and encouragement to staff about use of NRT, adherence to smoking restrictions by staff, routine (not left to staff discretion) assessment of patients' smoking status, routine recording of smoking status, routine provision of advice about quitting to patients by at least some staff, and monitoring of the recording of patients' smoking status on the unit.

To predict the provision of smoking care, eight characteristics of the unit and unit nurse manager and of policies and procedures (all with p values of <.25 in the chi square analyses) were entered into a logistic regression model. The variables were size of unit, nonuse of cigarettes as a reward for patients who smoke, restricted access to cigarettes for patients who smoke, nonprovision of cigarettes to patients when their supply is expended, withholding of cigarettes from patients who smoke in order to minimize tobacco-related harm, provision of information and encouragement to staff about use of NRT, routine (not left to staff discretion) assessment of patients' smoking status, and routine provision of advice about quitting to patients by at least some staff.

Discussion

The findings suggest that a majority of smoking patients in psychiatric inpatient units in New South Wales receive inadequate and inconsistent smoking care and that staff may be inadequately protected from exposure to environmental tobacco smoke. Although most psychiatric units enforced a total smoking ban indoors, no more than one-third of units (N=37, or 34%) had bans in place for all hospital grounds. This finding is consistent with previous research reporting that indoor bans were the predominant type of smoking ban in psychiatric inpatient settings (

12 ).

Although most nurse unit managers reported that they were responsible for enforcing the unit's smoke-free policy, only two-thirds (69%) reported that enforcement occurred. Previous research has indicated that when smoke-free policies were not consistently enforced, patients and staff tended to smoke without restriction (

37,

38,

39 ). Research has also shown that exposure to environmental tobacco smoke remained high in settings with designated smoking areas (

25 ). This finding was reinforced in the study reported here; nearly half of respondents (47%) reported that they had received staff complaints about exposure to second-hand smoke.

Eighteen percent of respondents reported that staff smoked with patients. This may reflect an attitude that smoking is an acceptable part of the culture of psychiatric inpatient units (

40 ) or that cigarettes are seen by patients and some staff as a currency for social exchange (

41 ). Research in a forensic psychiatric service (

17 ) and a large psychiatric hospital (

42 ) found that a majority of psychiatric staff and patients believed that staff should smoke with patients, with more than 90% of staff in both of these studies believing that patients' psychiatric status would deteriorate without access to cigarettes (

17,

42 ). Such beliefs are contradicted by evidence that shows that abrupt cessation has no effect on severity of symptoms (

24,

43 ) and does not have an impact on recovery (

43 ). Regardless of their determinants, these beliefs are considered to reinforce smoking behavior among both staff and patients (

41,

44 ), an outcome that contradicts health service guidelines internationally (

21,

45 ) as well as in Australia (

20,

32 ).

The results indicate that in New South Wales the level of adoption of smoking care guidelines in public psychiatric units is lower than in general hospital settings (

33 ). In the study reported here only half of the units always assessed patients' smoking status and just over a third of units (37%) always recorded smoking status in patients' records. Previous research suggests that there is little benefit to assessing smoking status if this information is not recorded and an appropriate intervention provided (

46,

47 ). In addition, 70% of respondents reported that patients were not assessed for nicotine dependence. Failure to diagnose and record nicotine dependence may reflect views of smoking as a choice rather than an addiction (

48 ) and may result from discretionary procedural guidelines (

32 ). The latter possibility is supported by the finding that more than half of the respondents indicated that the decision to assess and record smoking status and provide smoking care was at the discretion of staff.

In 2006, when this study was conducted, provision of smoking care was not mandated in psychiatric inpatient units in New South Wales (

32 ) and is now mandated in only one area of the state. Within this context, it is perhaps unsurprising that few units reported the provision of smoking care that would support abstinence, address withdrawal symptoms, or assist with a quit attempt. Controlling access to cigarettes was identified by respondents as the most frequently used form of smoking-related care, rather than best-practice smoking care alternatives such as providing advice on quitting.

Of concern is that more than one-third of respondents (36%) reported that they knew of patients who had begun smoking after admission. Previous investigators have suggested that this phenomenon stems from peer pressure from other patients to smoke, lack of other available activities, and reinforcement of smoking by the psychiatric unit (

13 ). In this study reinforcement of smoking was evident by the lack of consistency in the application of policies and procedures in regard to smoking bans, the presence of staff who smoked with patients, and less than optimal levels of smoking care. It has been suggested that legal ramifications may arise if a patient starts to smoke while an inpatient in a public health care setting (

48 ). Lawn (

48 ) proposed that if employers are aware that their day-to-day activities involve acceptance and reinforcement of smoking, despite contrary policy guidelines, negligence (in the legal sense) may be established.

There are also litigation concerns regarding an environment that allows and condones development or maintenance of nicotine dependence (

49 ). In this study respondents reported that staff provided cigarettes to patients who requested them, used cigarettes as a reward for good behavior, and provided cigarettes to patients to prevent negative behaviors. Failure of staff to warn patients of the harms of smoking or to take action to treat their nicotine dependence may leave staff vulnerable to litigation should patients develop smoking-related illnesses (

50 ). Although this has not been tested in Australia, failure to act appears to contradict duty-of-care responsibilities.

Other studies have reported that psychiatric staff have been cautious regarding the benefits of smoking bans and have been reluctant to provide smoking care in the inpatient setting (

9,

50,

51 ). Inconsistencies in staff management of these issues have led to greater difficulties for inpatients and staff (

23,

24 ). In the study reported here, the lack of association between the provision of smoking care and unit characteristics suggests that less than optimal provision of smoking care is systemic and not related to particular types of services (for example, acute or nonacute). The results suggest that units that showed signs of being able to break with traditional smoking-related practices were most likely to have documented unit policies on smoking restriction, staff compliance with smoking restrictions, increased provision of quit-smoking advice, and fewer staff who were smokers.

It has been suggested that staff training is part of the solution for ensuring consistent enforcement of smoking restrictions and provision of smoking care (

12 ). A small number (16%) of respondents reported that they had received smoking care training, and a majority of respondents (61%) reported interest in receiving such training. Others have also suggested that it is necessary to provide training that addresses skills, knowledge, and attitudes regarding the provision of smoking care and that provides knowledge and encouragement to staff about use of existing resources to improve the provision of smoking care, although it is arguable that such training is not sufficient (

12,

52 ). The New South Wales Health Department's existing guidelines for the management of nicotine-dependent patients (

32 ) provides a ready basis upon which training could be based.

This study relied on a self-reported questionnaire that is susceptible to respondent bias. Inaccurate reporting may have occurred if the respondents were not actively involved in daily smoking care activities. These data collection limitations may have led to misreporting (most likely overreporting) the extent of care provided (

52,

53 ).