The purpose of this study was to investigate whether the presence of substance-related disorders or mental illness may affect the quality of medication management in asthma care. We estimated the odds of patients with these conditions achieving established quality benchmarks for asthma care, while controlling for demographic factors. We hypothesized that patients with these conditions would be significantly less likely than patients without these conditions to achieve asthma medication quality standards.

Methods

We analyzed Medicaid claims for the year 1999 from five states representing different regions of the United States: Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, New Jersey, and Washington. For our study population we selected adults ages 18–56 and restricted our sample to patients whose files contained specific coding for asthma ( ICD-9 code 493.x) to minimize the inclusion of patients with other, nonasthma pulmonary conditions. Beneficiaries who had Medicare or private health insurance in addition to Medicaid were excluded, because claims from payers other than Medicaid were not available. We included patients with a minimum Medicaid enrollment of 30 days and controlled statistically for enrollment duration. Claims from each state were analyzed separately, because Medicaid benefits, demographic characteristics, and medical provider resources vary widely from state to state.

From this sample, we selected patients who met HEDIS persistent asthma criteria for our analysis. HEDIS technical specifications categorize a patient as having persistent asthma if he or she meets one of the following criteria in both the study year and in the year prior: one or more emergency department visits with a primary diagnosis of asthma; one or more hospital admissions with a primary diagnosis of asthma; four or more outpatient visits with asthma listed as any of the diagnoses, along with at least two asthma medication dispensing events; or four or more separate asthma medication dispensing events. Because our data set included claims only for calendar year 1999, it did not allow identification of persistent asthma criteria in two consecutive years, as described in the HEDIS specifications.

Rates of achieving the HEDIS quality standard (at least one long-term controller medication during the study year) and the quality measure described by Schatz and colleagues (

12 ) (a ratio of long-term controller medications to total number of asthma medications of ≥.5) were measured by using National Drug Codes from pharmaceutical claims. Patients who met our inclusion criteria but who had no documented dispensing events for any asthma medications were included in the analysis.

Patients in the sample with substance-related disorders were identified through ICD-9 coding (291.x, 292.x, 303.x, 304.x, 305.2–305.9, and 648.3). Coding for tobacco use disorders (305.1) was found only rarely and therefore was not included in the analysis. Patients with mental illness were identified through ICD-9 coding for major depression and other depressive disorders (296.2, 296.3, 300.4, and 311), anxiety disorders (300.xx, excluding 300.4), bipolar disorder (296.0–296.9, excluding 296.2 and 296.3), schizophrenia disorders (295.x), and other psychiatric disorders (297.x–315.x, excluding all diagnostic codes listed in other study categories).

We first compared the unadjusted proportions of patients with persistent asthma and substance-related disorders or mental illness who met either the HEDIS or the ratio quality measure. Statistically significant differences were identified with Fisher's exact tests, with significance defined as p≤.05.

By using logistic regression adjusting for age, gender, race or ethnicity, and length of Medicaid enrollment, we then estimated the odds of achieving these asthma quality measures at the individual level for patients with substance-related disorders and those with mental illness. Adjusted odds ratios for achieving each of the two quality measures are reported separately for patients with substance-related disorders, depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia disorders, and other mental illness.

Results

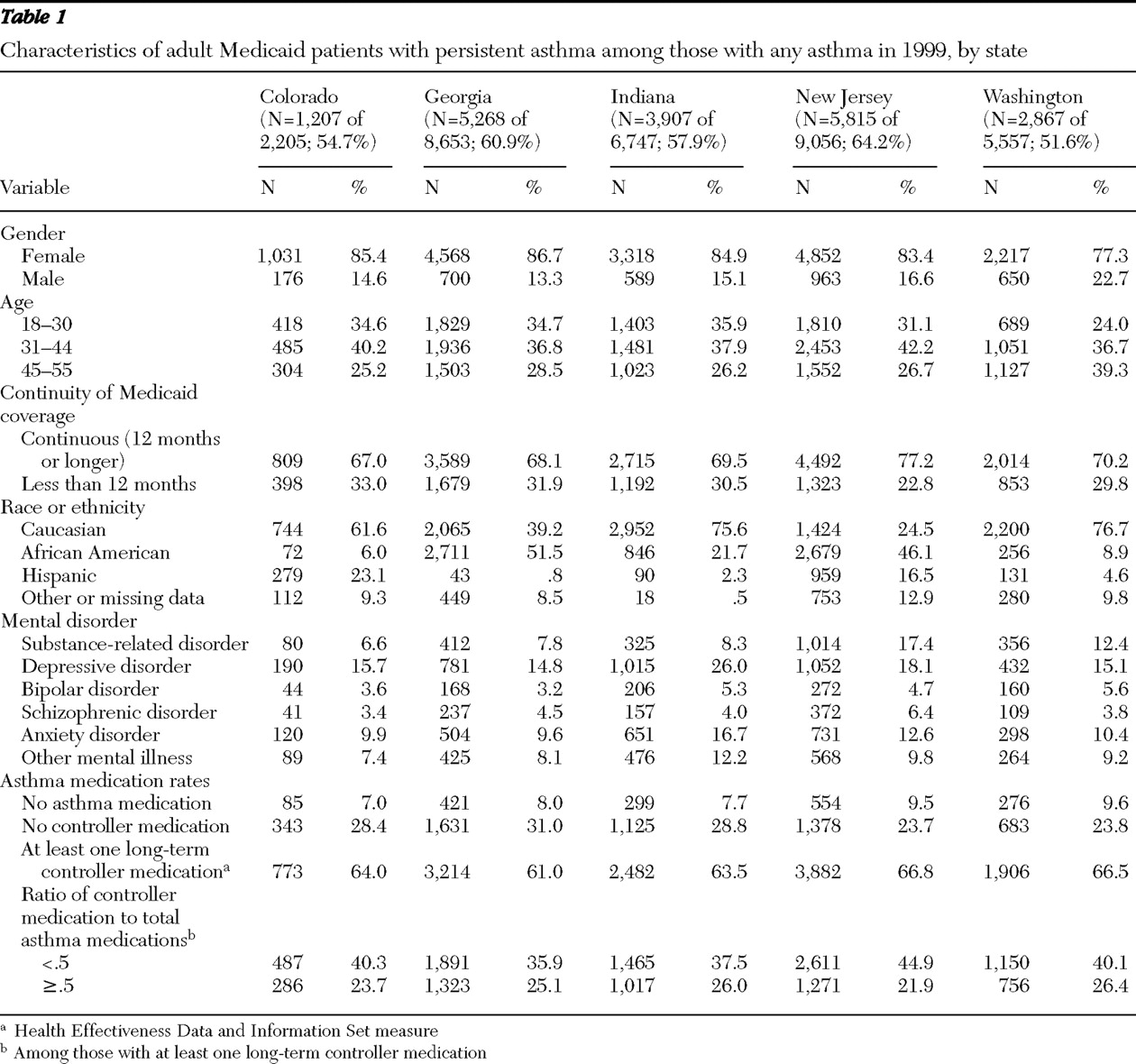

Initial samples of patients identified as having an asthma diagnosis ranged from 2,205 to 9,056, with over half of these patients meeting criteria for persistent asthma in each state (range 51.6%–64.2%).

Table 1 describes the composition for each state of the sample with persistent asthma, which was predominantly female (range 77.3%–86.7%) and relatively evenly distributed by age. Over two-thirds of the samples had Medicaid coverage for the entire study year (range 67.0%–77.2%). The racial composition of the samples varied widely by state.

Coding for substance-related disorders was found at rates ranging from 6.6% to 17.4%. Coding for mental illness was found at the highest rates for depressive disorders (range 14.8%–26.0%) and anxiety disorders (range 9.6%–16.7%). Coding for bipolar disorder ranged from 3.2% to 5.6%, while coding for schizophrenia disorders ranged from 3.4% to 6.4%. Other psychiatric diagnostic codes were combined into a single "other mental illness" category (range 7.4%–12.2%).

Approximately two-thirds (range 61.0%–66.8%) of the study sample met the HEDIS quality criterion of having at least one dispensing event for a long-term controller medication. Only about one-quarter (range 21.9%–26.4%) of patients meeting persistent asthma criteria achieved a ratio of controller medications to total asthma medications ≥.5.

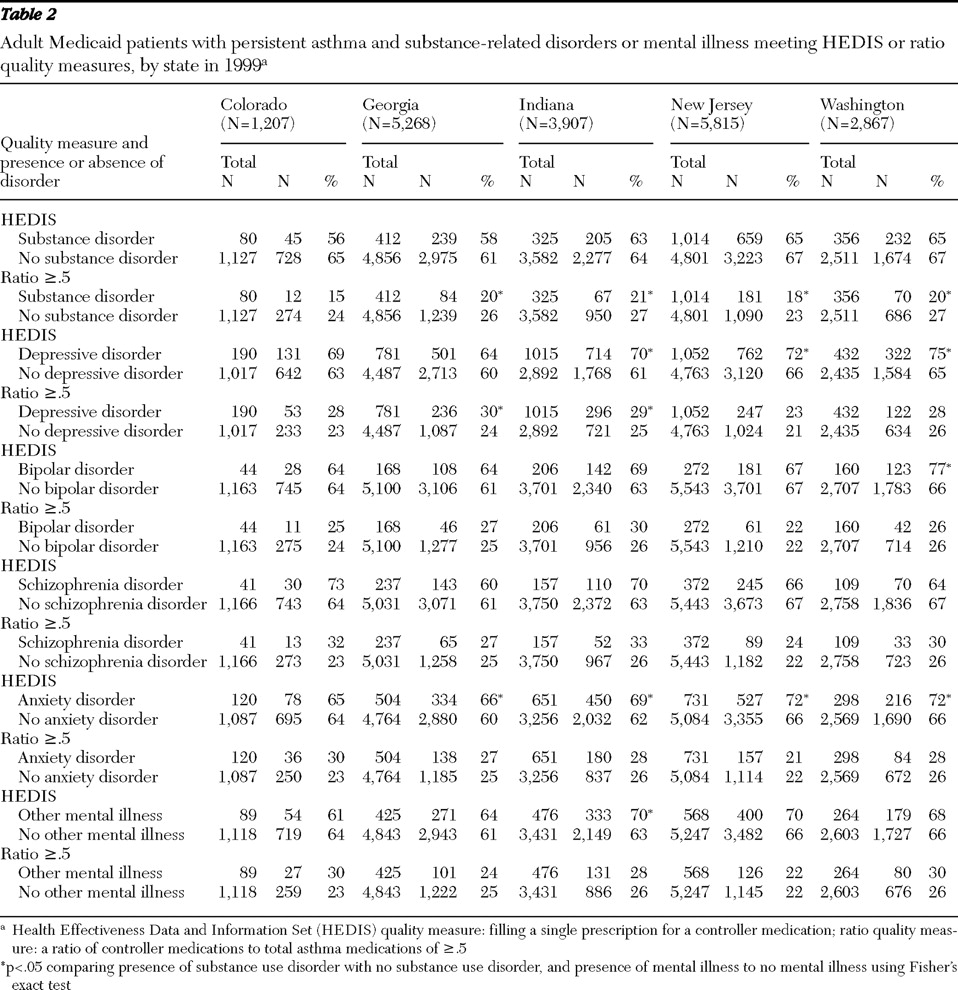

Analysis of the unadjusted data showed that patients with substance-related disorders achieved asthma care quality measures at lower rates than patients without substance-related diagnoses (

Table 2 ). For the HEDIS measure, these differences did not reach statistical significance. The rates of achieving the medication ratio of ≥.5 were significantly lower in the population with substance-related disorders in four of the five states studied.

Analysis of data for patients with mental illness showed dramatically different results: rates of achieving asthma quality measures trended higher for these patients (

Table 2 ). Patients with depressive disorders and anxiety disorders, respectively, were significantly more likely to meet the HEDIS quality criterion in four and three of the five states studied. Rates for patients with bipolar disorder and patients with other mental illness were significantly increased in only one of the five states. Evaluation of the ratio measure showed fewer significant differences. Patients with depressive disorders achieved the ratio measure at significantly increased rates in two of the five states studied, but differences were not significant in any state for any of the other mental illness categories studied. In the unadjusted data, patients with schizophrenia disorders showed no significant differences for either measure.

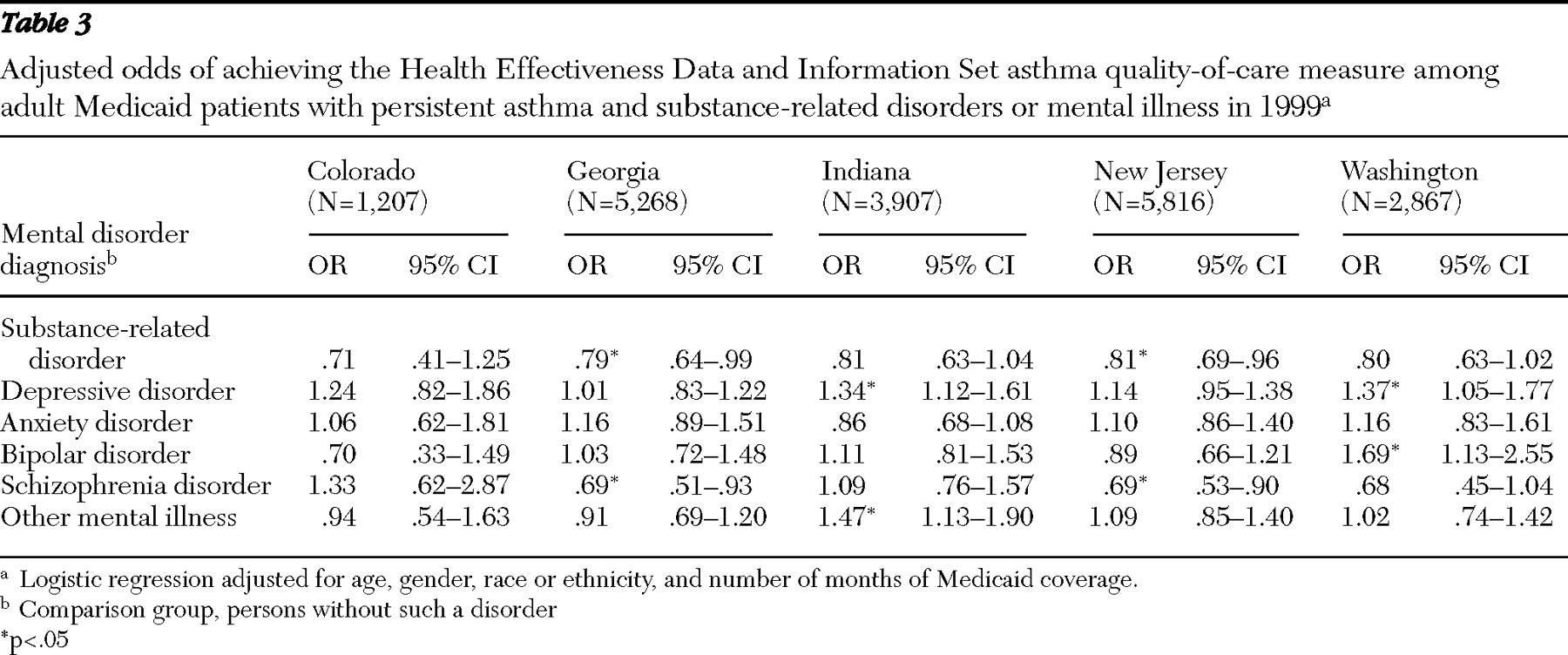

Many differences emerged when the data were adjusted for demographic characteristics, continuity of Medicaid coverage, and the presence of co-occurring substance-related or mental disorders.

Table 3 shows the adjusted odds of achieving the HEDIS quality measure. Patients with substance-related disorders showed lower odds of achieving the measure; the difference reached statistical significance in two states: Georgia (odds ratio [OR]=.79) and New Jersey (OR=.81). Patients in these two states were also less likely to achieve the HEDIS measure if they had a schizophrenia disorder: Georgia (OR=.69) and New Jersey (OR=.69). Odds of achieving the HEDIS measure were significantly increased for patients with depressive disorders in two states (Indiana, OR=1.34, and Washington, OR=1.37) and in one state each for bipolar disorder (Washington, OR=1.69) and other mental illness (Indiana, OR=1.47). Unlike in the unadjusted data, no significant differences were found for patients with anxiety disorders.

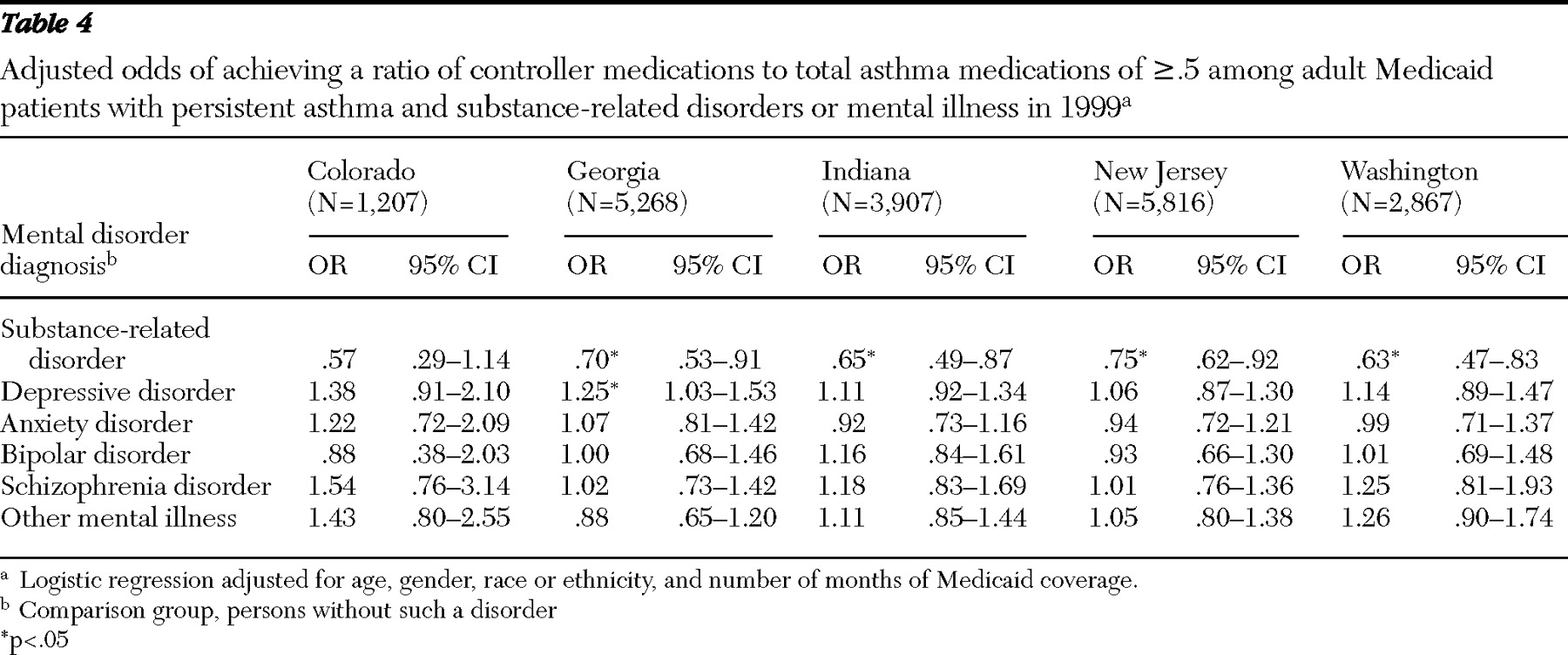

Table 4 shows the adjusted odds of achieving a ratio of long-term controller medication to total asthma medications of ≥.5. Odds of achieving this quality measure were significantly lower for patients with substance-related disorders in four of the five states studied, with odds ratios ranging from .63 to .75. For mental disorders, odds of achieving this measure differed significantly only for patients with depressive disorders and only in Georgia (OR=1.3).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that substance-related disorders and mental illness may influence rates at which patients achieve standardized asthma care quality measures, but this occurred in different ways than we originally hypothesized.

Past studies have shown that patients who abuse drugs may be at increased risk of severe asthma exacerbations or asthma death (

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30 ), but there has been little information to explain this association beyond the understanding that inhaled drugs may trigger severe asthma exacerbations. Our findings demonstrate that patients with substance-related disorders and persistent asthma fill prescriptions for controller medications at lower rates than patients without substance-related disorders. Although we cannot say whether these differences are due to differential access to care, decreased compliance with treatment recommendations, or the receipt of substandard care, these findings still may partially explain the disparities in asthma outcomes observed for these patients.

Decreased utilization of outpatient asthma care may also be a factor contributing to the decreased quality of asthma care for patients with substance-related disorders, because efforts to improve asthma care have largely focused on improving monitoring and prescribing practices in outpatient settings (

2,

3,

6 ). We have shown in a recent analysis (

31 ) that patients with substance-related disorders were half as likely as patients without these disorders to receive asthma care in outpatient settings, and therefore they may be less likely to benefit from outpatient-based quality improvement efforts.

Patients with mental illness showed more variable results. In general, with the exception of patients with schizophrenia disorders, patients with mental illness were equally or more likely to achieve the HEDIS asthma care quality measure, compared with patients without mental illness. These differences suggest that patients with some forms of mental illness may be receiving an enhanced level of care in some states, which may, in turn, be leading to improved compliance with quality guidelines. Patients with mental illness and asthma may have closer monitoring, more frequent contact with the medical system, or greater access to specialists, all of which may lead to a greater likelihood that their asthma will be recognized and treated with the initiation of controller medications.

In contrast, patients with schizophrenia disorders showed lower odds of achieving the HEDIS measure. As with patients with substance-related disorders, these differences could be due to barriers to accessing medical care, decreased compliance with treatment recommendations, or lower-quality medical care for asthma (

32 ). It appears then that even if in some states enhanced care for patients with asthma and mental illness is provided, this benefit may not extend to patients with schizophrenia disorders.

Our findings show some variability by diagnosis for patients with mental illness among the states, which may result from differences in sample sizes, rates of mental illness, diagnostic accuracy, the precision of coding, and differences in characteristics of the mental illnesses studied. Differences in care delivery systems and benefit structures among the states may also contribute.

Our results also show significant variability between the two quality measures. Only about one-quarter (21.9%–26.4%) of the patients in our samples met the ratio measure, and approximately two-thirds (61.0%–66.8%) of the samples met the HEDIS measure, even though both the HEDIS measure (

10,

33 ) and the ratio measure (

12,

34 ) have been shown to be predictive of some outcomes in selected samples. Patients with substance-related disorders showed lower odds of achieving both the HEDIS and the ratio measures, but the odds of achieving the ratio were more consistently decreased across the states. For patients with mental illness, differences found in the odds of achieving the HEDIS measure did not persist for the ratio measure. The HEDIS measure, which looks only at a single prescription filling event for a controller medication, may be more sensitive than the ratio measure to the influences of mental illness and mental health treatment on asthma care. On the other hand, the ratio measure may be capturing increased utilization of rescue medications among patients with substance-related disorders, which would increase the denominator in this measure and drive the ratios lower.

The variability between these measurements may also reflect some limitations in the current approach to assessing asthma care quality. Questions have been raised about the validity of the criteria for persistent asthma (

35,

36 ) that form the foundation for both of the quality measures used in this study. Many patients do not meet these criteria from year to year. The quantity of controller medications prescribed and adherence to those medications may be better predictors of utilization outcomes than the HEDIS benchmark, which measures the dispensing of only a single controller prescription (

10 ).

No studies have evaluated the association between existing administrative quality measures and clinical outcomes in high-risk subpopulations, such as patients with mental disorders, despite studies showing that patients with substance-related disorders (

27,

28,

29,

30 ) and some forms of mental illness (

37,

38,

39,

40,

41 ) may have poorer asthma outcomes. In addition, factors that are likely to affect the quality of asthma care and clinical outcomes in these populations are often not addressed by current quality assessment methods. For example, these measures do not incorporate any direct measurement of disease severity, which may be higher among patients with mental disorders. Smoking rates among patients with mental disorders are at least twice as high as those found in the general population (

42 ), but adjusting for tobacco use can be difficult when using administrative data. Patients using tobacco are also less responsive to inhaled steroids, suggesting that smoking may lead to poorer asthma outcomes, even when quality measures based on the use of inhaled steroids are met (

43,

44 ). Specific studies are warranted to examine the determinants of asthma care quality among patients with substance-related disorders and those with mental disorders and to examine the ability of administrative quality measures to predict improved clinical outcomes in these high-risk subpopulations.

This study draws from a large database of Medicaid claims and shows some consistency of results across multiple states despite differences in demographic characteristics and the structure of Medicaid-funded treatment services. Our findings, therefore, may be somewhat generalizable to other Medicaid populations, especially for patients with substance use disorders. We utilized existing, accepted measures of asthma care quality; the HEDIS measure is the current standard for comparing performance among managed care organizations (

36 ), and the ratio of controller medication to total asthma medications has recently been validated as being associated with improved quality-of-life scores and decreased future emergency and inpatient hospital utilization (

12 ). The assessment of asthma care quality in our study was facilitated by access to Medicaid pharmaceutical claims, which provided a comprehensive record of prescriptions filled by the Medicaid recipients included in the analysis.

This study is limited by having only one year of data available, making it necessary to identify patients with persistent asthma and measure their medication utilization within the same year. Our samples may include more patients with less severe asthma who would not meet persistent asthma criteria in consecutive years. Restricting our samples to Medicaid patients between the ages of 18 and 56 limits the ability to generalize our findings to other populations, and socioeconomic factors that may affect the quality of care, such as income, education level, and population density, were not evaluated. Also, our findings were derived from 1999 coding data and will not reflect any changes in asthma care guidelines, or improvements in adherence to those guidelines, that have taken place in the intervening years.

The persistent asthma designation is only a proxy for asthma severity; our data do not permit any direct measure of asthma severity, such as symptom ratings, quality-of-life scores, peak flow measurements, or pulmonary function testing. In addition, the quality measures studied evaluate rates of dispensing controller medications and do not include any direct measure of medication adherence. Finally, our study relied on administrative data to identify patients with substance-related disorders and those with mental illness. As such, a number of patients with these disorders may have been excluded from the analysis as a result of low rates of screening, lack of precision in making diagnoses, and incomplete or inaccurate diagnostic coding.