Involvement with police and the criminal justice system among individuals with mental illness has long been the subject of debate and discussion, but little attention has been paid to the role gender might play. Deinstitutionalization in favor of community-based care has increased the public presence and visibility of individuals with mental illness. Inadequate and inappropriate community treatment has relegated many men and women to the physical and social margins of society (

1,

2 ) and has increased the likelihood of their contact with the criminal justice system.

In one U.S. study, initial police contacts with persons who had a mental illness were shown to be higher than the prevalence of mental illness in the population (

3 ). Nearly 20 years later, in a methodologically different U.S. study, Engel and Silver (

4 ) found that police were nearly three times less likely to arrest individuals who had a mental illness. However, no information was provided in regard to how gender might have affected dispositions or arrest rates. Furthermore, the degree to which the results are generalizable to Canadian jurisdictions is unclear.

U.S. studies indicate that informal dispositions are used less frequently by police with persons who have a mental illness (

5 ). (In informal dispositions officers use their discretionary power to warn or divert an individual rather than laying a charge.) Studies in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom have shown that persons with mental illness are arrested and jailed for relatively minor offenses at a higher rate than the general population (

6,

7,

8,

9,

10 ). It has also been hypothesized that males and females are treated differently in the criminal justice system (

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22 ).

Men are more likely than women to commit criminal offenses and engage in violent behavior (

23 ). Traditionally, the criminality of women has been considered less of a social problem (

24,

25 ). Violence displayed by men is significantly more likely to result in injury (

26 ). Studies have shown that the gender gap observed in the general population in regard to violence and criminality may be smaller among individuals with a mental illness (

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38 ). In a large birth cohort study, Hodgins (

27 ) found that among persons with a severe mental illness or an intellectual disability, women were five times as likely and men were twice as likely as their counterparts without mental illness to have been charged with an offense by age 30. Other studies have shown that men and women with severe mental illness are, respectively, up to seven times and 27 times as likely to behave violently as men and women with no mental illness (

27,

28,

39 ). Such studies have led to the hypothesis that gender may play a mediating role in the relationship between mental illness and criminality or violence.

Furthermore, clinicians are less accurate in assessing violence risk among women compared with men (

40 ), which has been partly explained by the underestimation of base rates of violence among women with mental illness.

Most studies that have examined the role of gender in either criminal justice involvement or violence in general have been based on hospitalized populations of persons with mental illness or on samples of persons who have been charged or sentenced. No study has examined the role gender might play among persons with and without mental illness as they interact with police officers. This can have important implications for developing gender-sensitive assessment strategies and interventions in both mental health services and the judicial system.

The aims of this study were to determine rates at which men and women identified as seriously mentally ill account for initial and subsequent police contacts compared with individuals not identified as mentally ill. The study also compared the rates, patterns, and types of police contacts (offending behaviors, dispositions, and time to reoffense) of these groups.

Methods

This study is part of a larger project examining police interactions (

9,

41 ). Data were from the administrative database of the London Police Service (LPS), which tracks all interactions between the police and the citizens of London, Ontario, a midsized Canadian city (

41 ). This study received approval from the University of Western Ontario's Health Sciences Research Ethics Board through expedited review because only administrative data were used.

Participants

Data for January 2000 through December 2005 were extracted by using an algorithm to identify individuals with a mental illness (

41 ). Briefly, the algorithm first sorted individual records on the basis of three indications of mental illness: police caution flags, addresses, and key search words indicative of mental illness. If the algorithm indicated that a person had a mental illness, the evidence was then categorized into one of three levels of confidence: definite, probable, or possible mental illness. Classification of mental illness was based on the highest level of confidence over the six years reported for an individual. The group with definite mental illness represented .4% (N=1,491) of all individuals who had at least one contact with the LPS during the study period. The probable group represented .3% (N=975), and the possible group represented .2% (N=481). The remaining individuals were classified as not having a mental illness (99.2%; N=353,490). To avoid possible contamination effects and increase comparability with other studies, only the group with a definite mental illness (hereafter referred to as the group with serious mental illness) was compared with the group without mental illness.

The presence of one of the two following criteria was regarded as a likely indicator that an individual had a serious mental illness. Either the individual had a current or past address of a psychiatric hospital, psychiatric ward of a general hospital, provincial long-term care home, a residence supported by a mental health housing agency, a shelter, or a hostel or the individual's name came up when the database was searched with terms in police records that refer to civil or criminal Canadian legislation pertaining to mental illness, such as "not criminally responsible," "Mental Health Act," "Form 3," "psychiatric disability," and similar terms, in addition to the presence of any of four national or local police caution flags related to mental illness ("mental instability," "possible suicide," "mental disability/senility," and "suicidal tendency") in the person's record. All persons in the sample were at least 18 years old at the time of their first contact with police during the six years of the study.

Measures

Type of contact. A contact was defined as an interaction between the police and the public in any of four ways: complaints; general occurrences, tickets, or bylaw infractions; Provincial Offense Notices (hereafter called notices); or street checks. Any call for service received by police is labeled a complaint. To record a complaint for future reference or because a charge will be laid, the investigating officer documents the information in a more formal report called an occurrence. For an offense notice (such as traffic violations and trespassing) or a city bylaw infraction (such as noise and public disturbances) the officer writes a ticket or a notice. For informal collection of information on suspicious persons and unusual activity, the officer writes a street check.

The main unit of analysis in this study is the individual. An individual may have been involved in many of the four contacts.

Type of offense. In some contacts the individual is the suspected perpetrator of an offense and considered as an offender. In addition to a cumulative category of any offense, six categories of offense were coded: violence, property offense, offense related to the administration of justice (for example, failing to attend court or breach of a court order), notices and bylaw infractions, drug- and alcohol-related offenses, and other offenses.

Type of response. Offenders were categorized into two groups on the basis of the system's response to their suspected offense. The formal group consists of individuals for whom a charge was laid. Individuals in the informal group could be suspects, could have received a warning, or could have been under investigation, but they were not charged.

Recidivism was defined as any new interaction with the LPS as a suspect of an offense during the study years.

Analyses

Descriptive statistics, such as frequencies, means, and standard deviations, were generated. Odds ratios (ORs) at 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated for nominal data and are presented both within gender categories and within mental health status. The analysis used t tests for continuous variables. Kaplan-Meier survival analyses were conducted to calculate time to reoffense for individuals who had been suspected of an offense, and the Lifetest procedure from SAS was used to account for uneven follow-up periods (

42 ). Four strata were used: men with serious mental illness, women with mental illness, men without mental illness, and women without mental illness. Log-rank tests were then used to conduct pairwise comparisons. Given the large sample, many observed differences were statistically significant.

Results

Any contact with police

Between 2000 and 2005 there were 767,365 contacts between citizens and the LPS, with a yearly average of 127,894.2±10,237.4 interactions. Information about gender was unavailable for 231 individuals, who were dropped from the sample. A total of 146,753 women (41.2%) and 209,684 men (58.5%) were involved with the LPS; these women had 343,878 contacts and the men had 585,975. Some contacts with police involved more than one man or woman.

Men and women with serious mental illness represented, respectively, .5% (N=954) and .4% (N=537) of all men and women who had at least one contact with the LPS; however, they were involved in 3.2% and 3.0% of all interactions, respectively. Men and women without mental illness represented, respectively, 99.0% (N= 207,649) and 99.4% (N=145,841) of all men and women who had at least one contact; they were involved in 95.3% and 96.7% of all interactions, respectively.

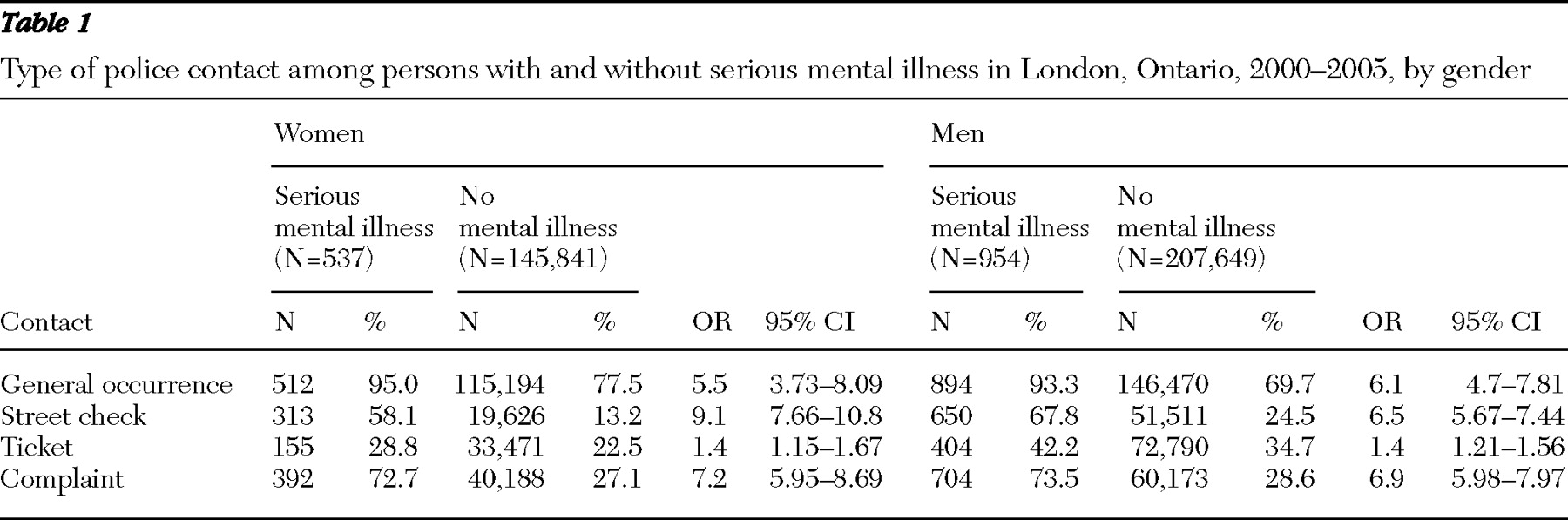

Men and women had similar rates of contacts involving tickets, complaints, and general occurrences within mental illness status categories. However, women with serious mental illness were 9.1 times as likely as women without mental illness to be involved with police through street checks; for men the odds ratio was 6.5 (

Table 1 ). Men and women with serious mental illness were, respectively 6.9 and 7.2 times as likely as their counterparts without mental illness to have been the source of complaints.

Suspected offenders

Between 2000 and 2005 a total of 80,356 men (38.3%) and 36,327 women (24.8%) were suspected of committing an offense. Of these, persons with serious mental illness represented .7% (N=825), and those with no mental illness represented 98.5% (N=114,943). Among all suspected offenders, the proportion of men with mental illness was greater than the proportion of men without mental illness (60.7% [N=579] compared with 38.1% [N=79,033]) ( χ 2 <.001), and the same was true for the proportions of women with and without mental illness (45.8% [N=246] compared with 24.6% [N=35,190]) ( χ 2 =129.13, df=2, p<.001).

Types of offense

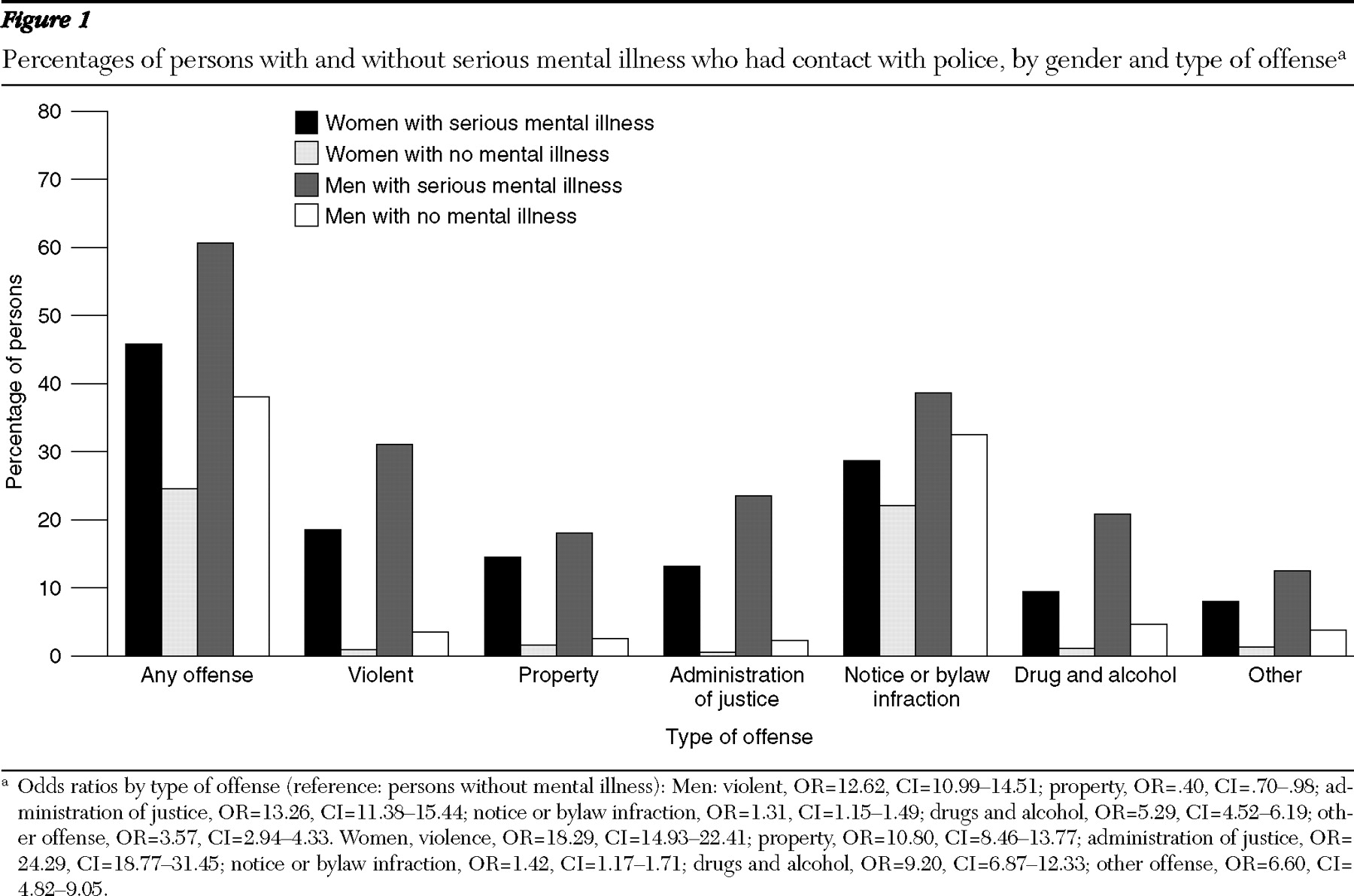

Figure 1 shows the rates of the various types of offense among the groups. Women with serious mental illness were 2.6 times as likely as women without mental illness to have had contact with police as an offender (CI=2.18–3.07), and 18.3 times as likely to have had a violent offense. For men with mental illness, the odds of having police contact as an offender were 2.5 times as high (CI=2.21–2.86) and 12.6 times as high for violent offenses.

Among persons without mental illness, men were nearly twice as likely as women (OR=1.88, CI=1.85–1.91) to have been suspected of an offense, and among those with mental illness, men were 1.7 times as likely as women (CI=1.43–1.92). Men with mental illness were twice as likely as women with mental illness to have committed a violent offense (OR=1.98, CI=1.53–2.55). However, among those without mental illness, men were nearly four times as likely as women to have committed a violent offense (OR=3.73, CI=3.51–3.94). No differences between men and women with mental illness were found for property offenses and other offenses. Regardless of mental illness status, men were more likely than women to have had contact with police for administration of justice, drug and alcohol, and other offenses. However, the odds ratios between men and women with serious mental illness tended to be half those observed between men and women without mental illness.

Type of response to offenses

Among the 100 women with serious mental illness who committed a violent offense, 96.6% (N=96) were formally charged, compared with 1,213 of the 1,392 women without mental illness (87.1%) who committed a violent offense (OR=3.5, CI=1.29–9.75). Among women, those without mental illness were more likely than those with mental illness to be charged for notices and bylaw infractions (OR= 37, CI=22.72–58.82). Among the 297 men with serious mental illness who were suspected of a violent offense, 97.3% were charged (N=289) compared with 6,722 of the 7,179 men (93.6%) without mental illness who were suspected of committing a violent offense (OR=2.5, CI=1.21–4.99). For property offenses, men with serious mental illness were 3.3 times as likely as men without a mental illness to be formally charged (CI=1.20–8.82). No differences between groups were found for other offenses.

Among individuals with serious mental illness, men were more likely than women to be charged when the police contact involved a violent offense (OR=3.30, CI=1.80–6.18) or when it involved an offense notice (OR=1.9, CI=1.06–3.51). Among persons without mental illness, men were twice as likely as women to be formally charged for violent offenses (OR=2.17, CI=1.81–2.61), 1.5 times as likely to be charged for notices (CI=1.23–1.91), 1.7 times as likely to be charged for drug-related offenses (CI=1.33–2.24), and 1.6 times as likely to be charged for other offenses (CI=1.01–2.58).

Number of offenses

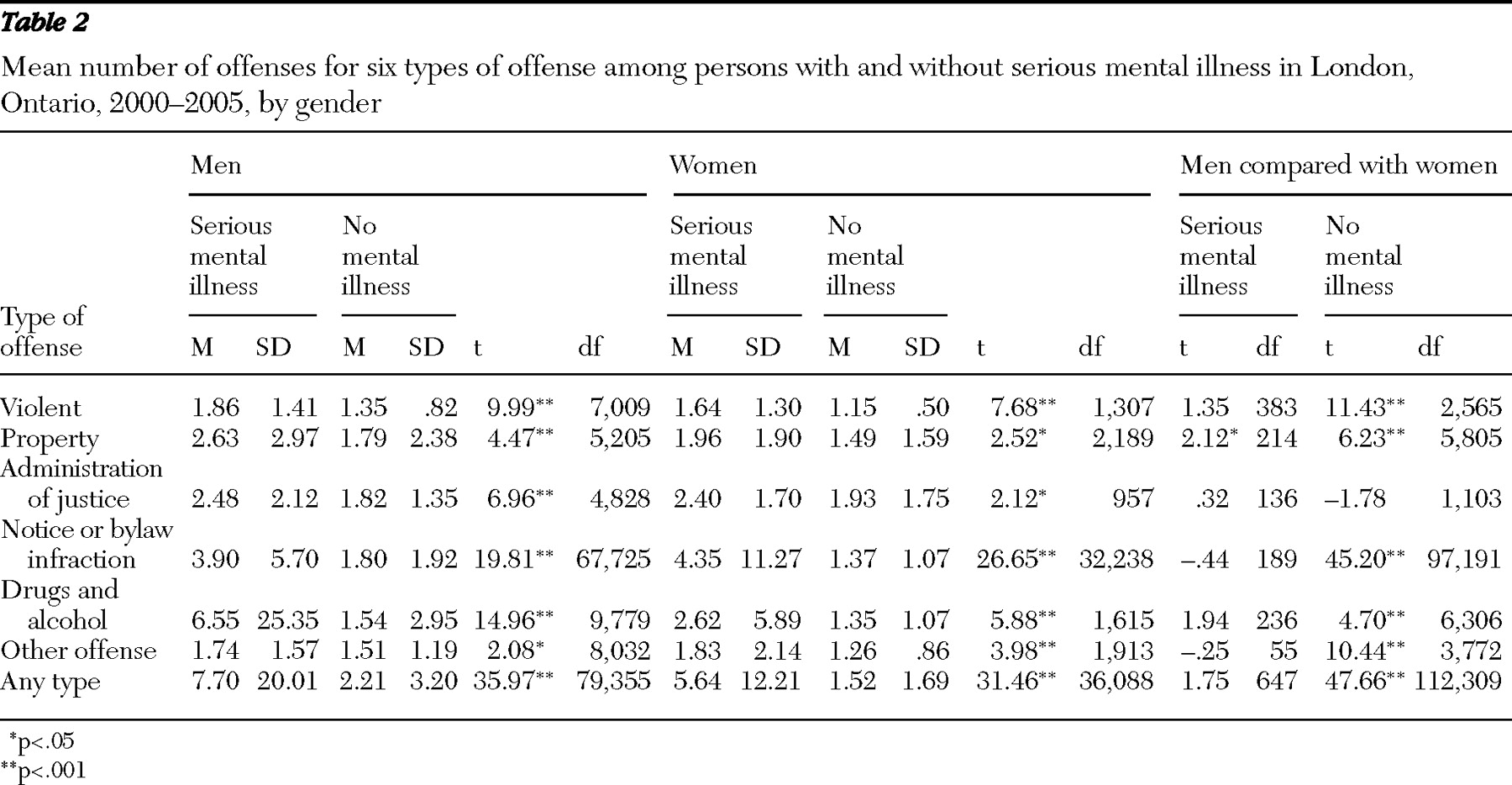

As shown in

Table 2, among both men and women, those with serious mental illness had more offenses on average than their counterparts without mental illness. There were no gender differences among persons with serious mental illness in the mean number of offenses in any of the six categories. However, among those without mental illness, men had a higher average number of offenses in all categories than did women.

Reoffending

Among persons without mental illness suspected of an offense, 34.4% of men (N=27,218) and 21.8% of women (N=7,840) had a new contact with police as a suspect within the six study years, compared with 70.6% (N=409) of men with serious mental illness ( χ 2 =332.14, df=1, p<.001) and 61.1% (N=150) of women with serious mental illness ( χ 2 =217.46, df=1, p<.001). Gender comparisons within mental health status revealed that men were more likely than women to have a new contact as an offender but that the gender gap was smaller among individuals with serious mental illness ( χ 2 = 1,851.13, df=1, p<.001). Although the gender gap was smaller among those with serious mental illness, men were also more likely than women to have a new contact as an offender ( χ 2 =7.38, df=1, p<.01).

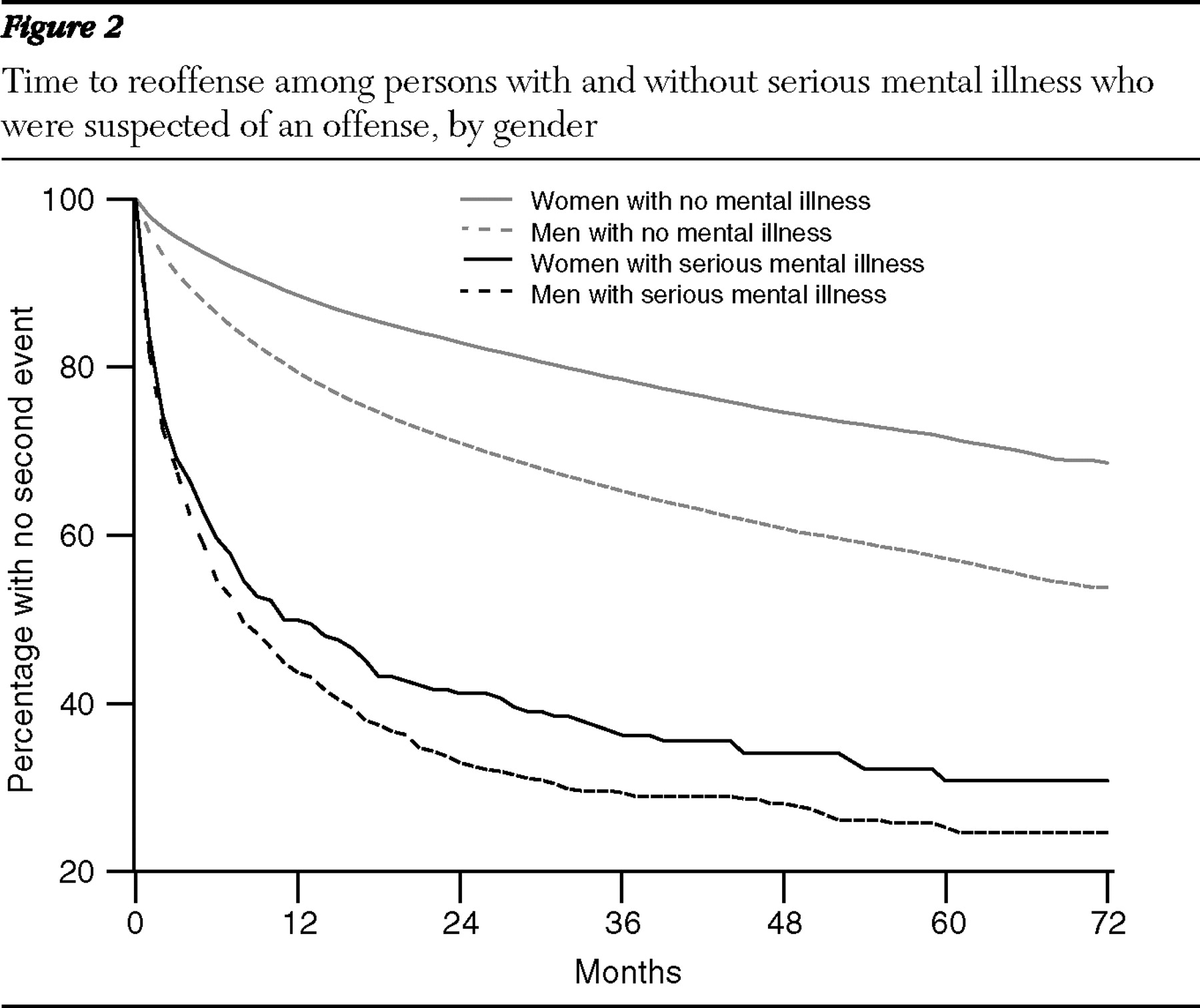

Figure 2 displays the time-to-reoffense survival curves for the four groups. Pairwise comparisons indicate that for both men and women, individuals with serious mental illness became involved in a second offense sooner (for the difference between men,

χ 2 =521.35, df=79,612, p<.001; for the difference between women,

χ 2 =308.78, df=36,156, p< .001). Again, the gender gap was significantly larger among those without mental illness (

χ 2 =1,892.76, df=114,943, p<.001) than those with serious mental illness (

χ 2 =7.58, df= 825, p=.006).

Discussion

The strength of this study lies in the large sample size and in the fact that it examined all interactions of an urban police service over a long period. To our knowledge, the LPS data set is the only administrative data set of actual police contacts with individuals with a mental illness that has been used for research with published results (

9,

41 ). The study found that both men and women with serious mental illness represented a small proportion of all individuals who came into contact with LPS. In fact, people with serious mental illness seem to be underrepresented compared with the prevalence rates of serious mental illness among men and women in the general population. However, persons with mental illness were more likely to have multiple contacts with police compared with those without mental illness. Thus the former group used a larger amount of resources per individual.

Key findings

Among all persons in contact with police, those with mental illness were found to be more likely than those without mental illness to have contact with police through street checks and complaints, which indicates that they are sought out more often as a group by police and complained about by other citizens. Persons with mental illness were also more likely to have contact with police as a suspect in an offense. Among those with serious mental illness who had contact with LPS, approximately one-third of men and one-fifth of women were suspected of a violent offense, and an even larger proportion of men and women with mental illness were involved in minor offenses. Both men and women with mental illness had higher rates of substance-related offenses than their counterparts without mental illness.

The type of interactions that a group has with the police can have a substantial effect not only on police perception of them but also on public perception. Even though persons with mental illness accounted for less than 1% of all individuals with whom police interacted, police officers were more likely to come into contact with them in the context of offending behavior compared with other citizens. Such encounters may lead to a very biased view of persons with mental illness; police officers and citizens who witness these interactions may regard persons with mental illness as criminals and as possibly violent.

Police officers have various degrees of discretion depending on the situations they encounter, and they may choose to handle some situations informally, through warnings or diversion to mental health services, or in a more formal manner, such as by making an arrest. Consistent with other studies (

6,

7,

8 ), this study found that individuals with a mental illness suspected of an offense were more likely to be formally charged with an offense than individuals who did not have a mental illness. The study went further by showing that this finding varied according to gender and type of offense. For example, compared with women with no serious mental illness, a formal disposition was used less often for women with serious mental illness for notices and bylaw infractions. Both men and women with serious mental illness who were suspected of violent offense were more likely than their counterparts without mental illness to be formally charged.

Finally, men and women with serious mental illness who were suspected of an offense had a greater number of repeat encounters with police than those without mental illness and they committed a second offense sooner. This finding has important implications because it involves the allocation of substantial police resources to deal with the same individuals revolving through the criminal justice system. Although this study did not gather data on the duration of police encounters, other studies have long shown that police interactions with individuals who have a mental illness are more time-consuming than interactions with the general population (

43,

44,

45 ). During this study, mental health treatment services in London, Ontario, were in the process of shifting from being hospital based to being community based. Hospital-based services became increasingly difficult to access, and community-based services were not in place, which left the police with fewer informal options.

An increasing number of studies using a variety of samples and sources of information have shown that the gender gap regarding violence and criminality among individuals with a mental illness is smaller than among individuals from the general population, which indicates that mental illness may be an important moderator of the relationship between gender and violence. Mental illness may be a more important risk factor for offending and violence among women than among men (

27,

29,

33 ). The findings of this study indicate that for all police interactions with citizens, the gender gap is smaller among persons without mental illness than among those with mental illness for type of offense, police response to an offense, number of offenses, reoffense rates, and time to reoffense. As Stueve and Link noted (

33 ), if the relation between violence and gender is unique among individuals with mental illness, women with mental illness may not be receiving appropriate interventions that address their specific needs. Considerable advancements in the field of risk assessment and management and in evidence-based practices for persons with serious mental illness have been made over the past decade; however, little attention has been paid to how these practices may affect women as they move through the mental health and criminal justice systems.

Limitations

Several caveats apply to interpretations of the results of this study. First, the data set was administrative, and no interrater reliability checks were performed on coding of police contacts. Second, the contextualization of specific events was not possible because of the small number of variables available in the database. Third, the data are representative of all individuals who came into contact with police in a midsize Canadian city but not representative of persons with mental illness. Fourth, the analyses excluded individuals who were identified by the initial algorithm as being in the possible and probable categories of mental illness (

41 ) because we had less confidence in the validity of those components of the algorithm. Some individuals with serious mental illness may have been in those categories and were therefore not included in the analyses. The two other groups accounted for .5% of individuals in contact with police over the six years studied, and their inclusion would still have resulted in an underrepresentation of persons with mental illness in contact with police services.

Fifth, because classification of persons with mental illness relied heavily on institutional and supportive housing addresses, the algorithm may have missed some individuals with serious mental illness who lived independently or who were homeless but not in shelters. London, Ontario, has shelters for between 360 and 500 people. In London it is estimated that approximately 1,500 citizens are homeless on any given day. However, not all homeless individuals need to use shelters. Some "couch surf" and cycle in and out of shelters, which do not turn anyone away without alternative arrangements. Overall, London does not have the same problems with lack of temporary shelters that some larger urban communities have. The algorithm thus did not identify individuals who had never been institutionalized and were living at home or independently. Other studies that use administrative or institutional data have the same limitation: there is no other way to identify mental illness in an administrative database without diluting and introducing bias into the definition.

Conclusions

The relationship between mental illness and involvement with the justice system is complex and is the object of ongoing debate (

46 ). Mental illness may be directly associated with criminality, may increase or decrease certain risk factors related to criminality, and may affect the level of attention paid to individuals because of their bizarre behavior or because the system lacks resources to address their problems. However, mental illness clearly increases the complexity of police interventions, and involvement with the judicial system increases the complexity of and access to mental health care (Crocker AG, Côté G, Braithwaite E, unpublished manuscript, 2008).

Although individuals with severe mental illness represent a small proportion of all individuals in contact with police services, the results of this study underscore the need for expanded prearrest diversion programs and for the allocation of more resources to meet the needs of persons with serious mental illness, because these individuals tend to have more repeat encounters with police for a variety of offenses compared with persons without mental illness. The results also support the contention that the gender gap in regard to criminality among individuals with serious mental illness may be smaller than in the general population. However, the needs and problems of men and women may be different, and thus, as has been suggested elsewhere, gender-specific interventions should be used to address the involvement with police of men and women who have mental illness (

47 ).

Administrative police databases, such as the one available in London, Ontario, can be used as a powerful low-cost tool to identify changes in patterns of police contacts with persons with mental illness after the implementation of diversion programs, changes in police training in regard to mental illness, the advent of new legislation, or the implementation of new programs or resources for men and women at risk of contact with police officers.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported by a grant from the Canadian Donner Foundation and by a grant from the Change Foundation, both to Dr. Hartford. Preparation of the manuscript was supported by a grant to Dr. Crocker from the Consortium for Applied Research and Evaluation in Mental Health. Dr. Crocker acknowledges the support, in the form of consecutive salary awards, of the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec and the Canadian Institute of Health Research. The authors thank London Police Service Chief Brian Collins, Chief Murray Faulkner, as well as Annette Swalwell, Eldon Amorioso, Corrine Enright, and Hazel Rona. The authors thank Amelia Yakobchuk, Marcus Juodis, and Landika Fajdiga. They also thank Larry Stitt, M.Sc., for conducting most of the statistical analyses and Jean-François Allaire, M.Sc., and Julie Meloche, M.Sc., for additional statistical consultation.

The authors report no competing interests.