Participants

Mothers of four- to ten-year-old children who were participating in a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of depression treatments for low-income women from racial-ethnic minority groups (

29 ) were eligible to participate in a substudy focusing on children. In the treatment study, 66% of eligible women who screened positive for depression participated. Of the 223 mothers who were eligible for the child study, 133 (60%) participated. Mothers gave written informed consent to participate with their four- to ten-year-old child, and children seven and older gave their assent. Two-thirds of the mothers had major depressive disorder, and the others were free of psychiatric disorder. There were no differences between those who did and did not participate, in terms of maternal age, ethnicity, number of children, child's age, child's gender, or, among the women with depression, their initial depression assessment score.

Half of the children had a biological father living in the home with the mother and child. For the others, a father or father figure was selected to be interviewed if the child saw him at least once per week, with the selection prioritized for whom to interview as follows: biological father not in the home; foster father, stepfather, or adoptive father in the home; stepfather or adoptive father not in the home; or the person the mother described as "most like a parent" to the child. This procedure yielded a father figure (hereafter referred to as "father") for 122 (92%) children. Of these, 111 (91%) mothers gave consent to contact the father for a phone interview, and 83 interviews with fathers (62% of sample) were completed. Among participating fathers, 62 (75%) lived in the home and 50 (60%) were biological fathers—rates that were not significantly different from those of the nonparticipating fathers. For the 118 children who attended school, interviews were completed with 89 (75%) of their teachers.

Measures

Maternal depression. Women were screened for depression with the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD) (

30 ), which has been validated as an effective method for identifying depression among primary care medical patients (

31,

32 ). Women who screened positive were assessed by trained lay interviewers with the Comprehensive International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (

33 ), a structured psychiatric interview that uses the criteria of the

DSM-IV (

34 ).

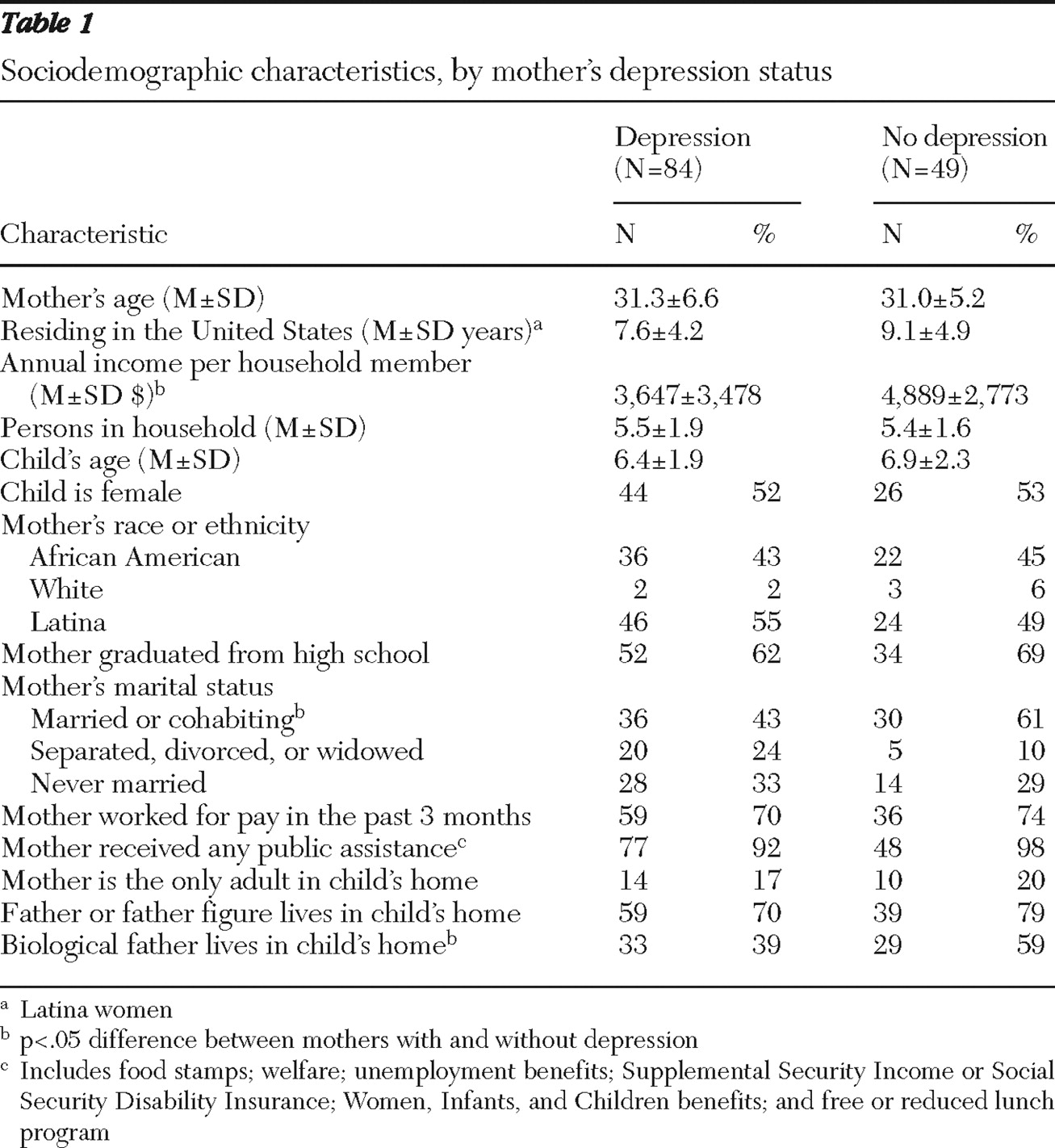

Sociodemographic characteristics. Mothers reported their age, ethnicity, education, marital and employment status, income, receipt of public income assistance, and their child's age, race-ethnicity, gender, and grade in school.

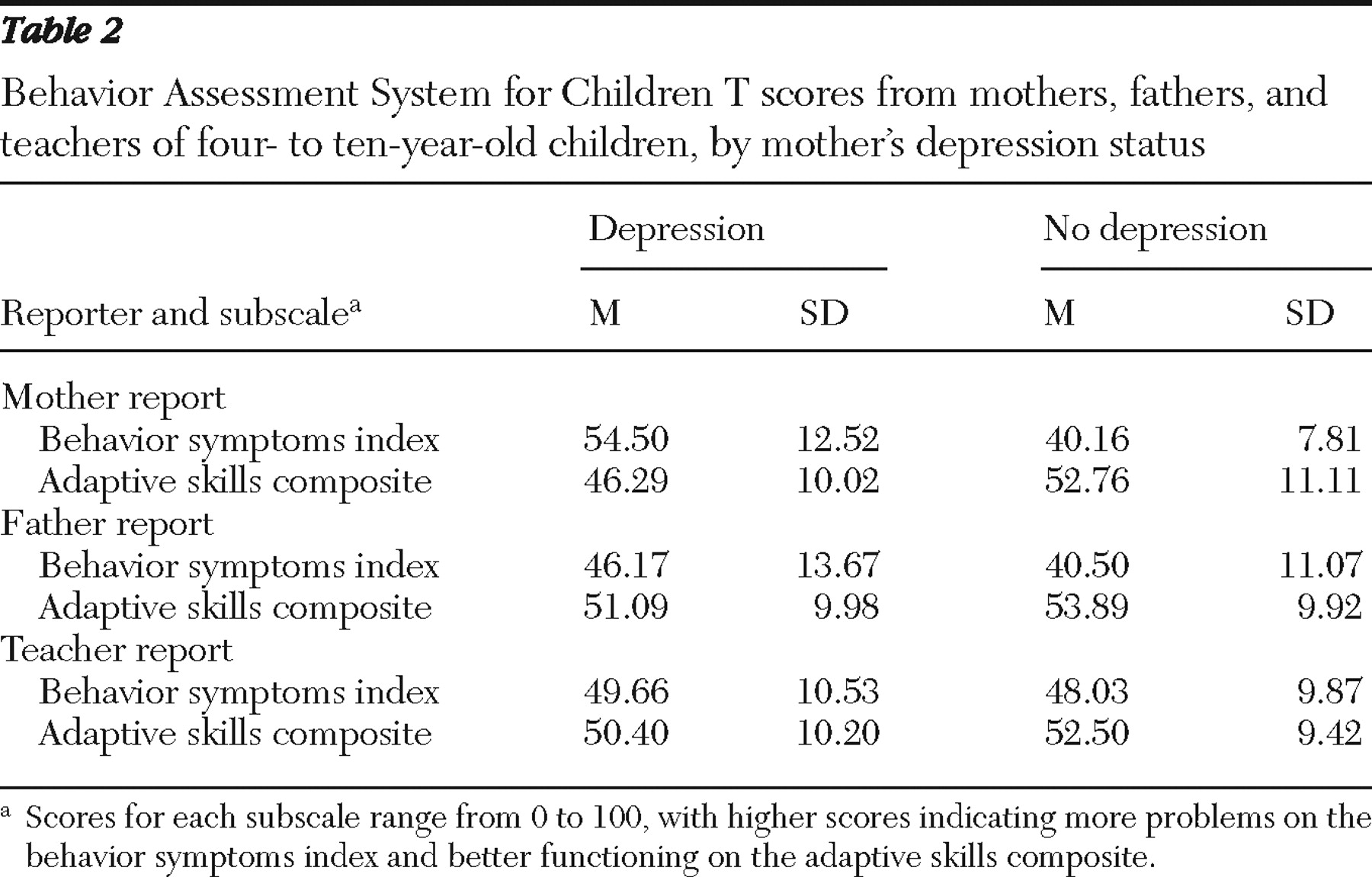

Children's emotional and behavioral problems and adaptive skills. Mothers, fathers, and teachers completed the appropriate version of the Behavior Assessment System for Children (BASC) (

35 ), which provides a parent report scale and teacher report scale for preschool-age children (ages four and five) and for children aged six through 11. The BASC is a set of conceptually based scales for rating child behavioral and emotional problems and social and adaptive functioning on a 4-point frequency scale. Results are reported as mean±SD T scores (T=50±10, range 0–100) that are age- and gender-normed based on a nationally representative sample. Both age versions of the parent and teacher report scales include two aggregate scales, the behavioral symptoms index (BSI) and the adaptive skills composite (ASC). The BSI is a measure of emotional and behavioral problems that combines the subscales of depression, anxiety, aggression, hyperactivity, attention problems, and atypicality. Higher BSI scores indicate more problems. The ASC measures social and adaptive functioning by combining the subscales of social skills, leadership, adaptive skills, and (from teachers only) study skills. Higher ASC scores indicate better functioning. The aggregate scales in both versions have excellent reliability, with internal consistency coefficients above .85 and retest reliability above .90 (

35,

36 ).

Composite measures of parenting and family environment. In order to provide a single robust, composite measure of parenting and of family environment, multiple scales completed by mothers were subject to principal-components analysis. For both constructs, the first factor was used as the composite measure, because it explained a large amount of the variance and adequately fit the data (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin test of sampling adequacy=.58 and .73 for parenting and family environment, respectively). The two composite scales were standardized with z scores (z=0±1, range -3.0 to 3.0) and coded so that higher scores indicated more positive parenting and family environment.

The parenting quality composite included four variables: two subscales from the Children's Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (

37,

38 ), rejection (ten items;

α =.72) and consistent discipline (eight items;

α =.83), and two subscales from the Conflict Tactics Scales—Parent- Child version II (

39 ), nonviolent discipline (four items;

α =.76) and psychological aggression (five items;

α =.77).

The family environment composite included five variables: stressful life events that the family had experienced in the previous year, adequacy of 15 resources assessed with the Family Resources Scale (

40 ), family involvement based on the eight-item subscale from the parent report of the Child Health and Illness Profile—Child Edition (

41 ), emotional and instrumental social support (

42 ), and marital and relational conflict (

42 ). Additional details on these composites are available from the first author.

Procedures

Recruitment was a multistage process involving screening for depression in more than 20 public health and social service settings and confirmation of the diagnosis by the CIDI structured interview. Eligible mothers were recruited into the child study by the staff of the treatment study (

29 ). All procedures were approved by the relevant institutional review boards.

All mothers, with and without depression, completed a two- to three-hour interview in their home that was conducted by trained interviewers blind to mothers' depression and treatment status. Separate interviews with children lasted 45–90 minutes. Interviews were completed in Spanish, as needed, by bilingual interviewers. Interviews were completed an average of 7.8±5.0 weeks after mothers' identification for the treatment study, with 16 (19%) mothers in the depression group having a treatment visit at least one day before the baseline interview for the child study. No effects of beginning treatment before the baseline child study interview have been detected with the use of multiple analytic approaches.

Data analytic strategy

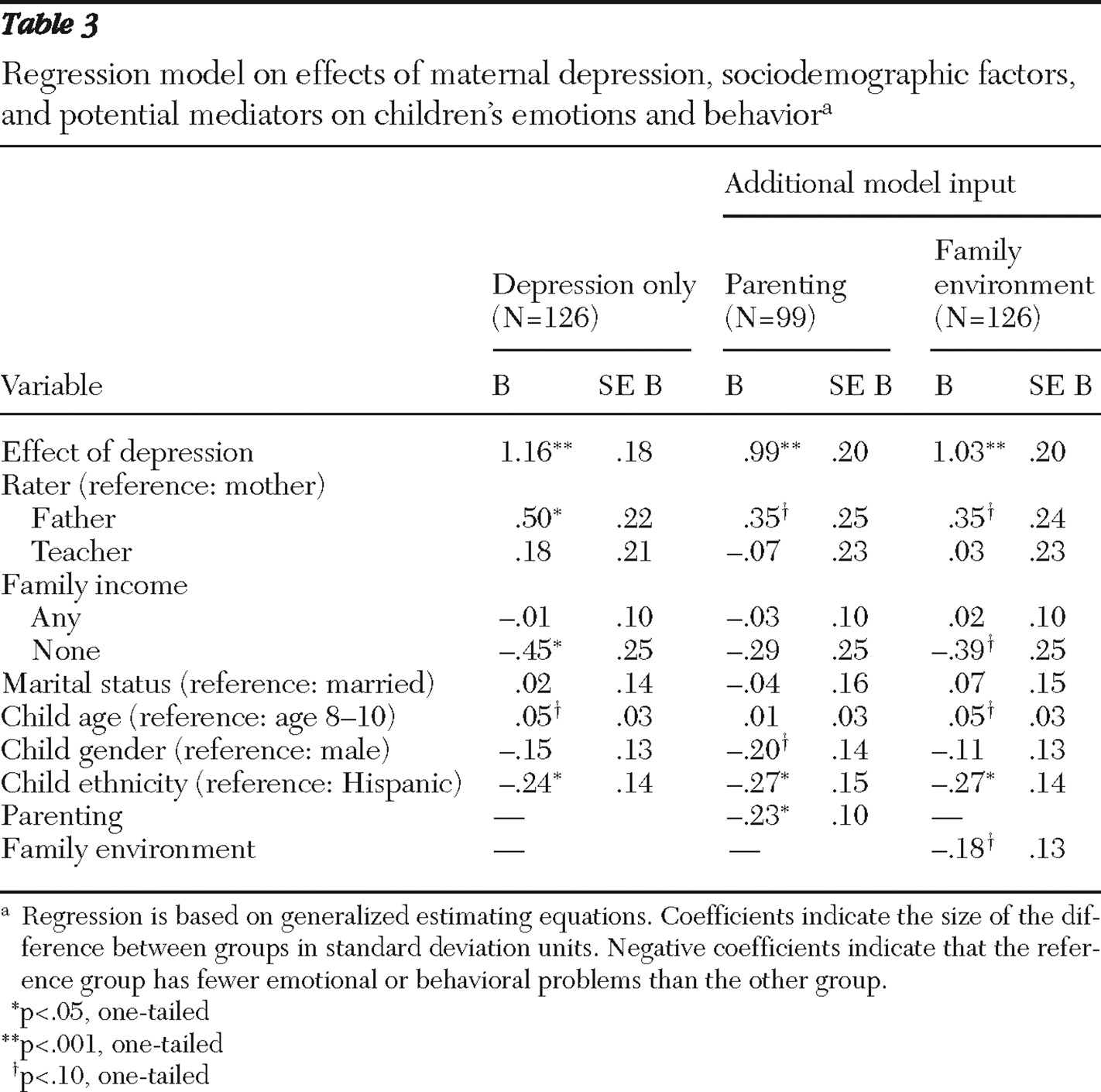

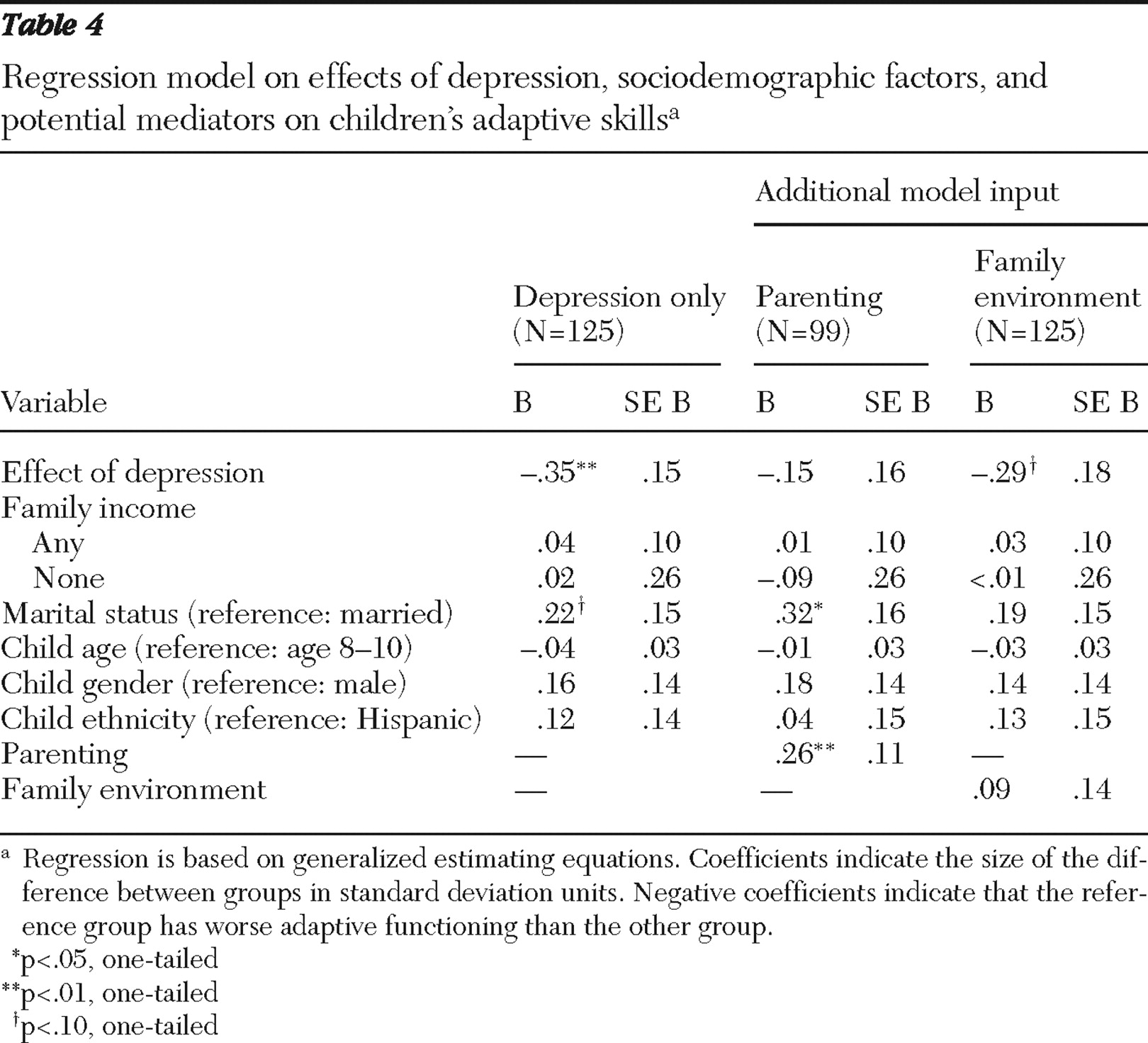

Multireporter, cross-situational assessments of children's behavior and social competence were obtained to reduce the bias of any one reporter, but the reports were too poorly correlated (range .21–.42) to simply combine them, a finding typical in the informant concordance literature (

27,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47 ). Generalized estimating equation (GEE) methodology (

48 ) was used to examine the extent to which mothers', fathers', and teachers' reports of each of the child outcomes were concordant. When reports were not concordant, linear regression models were fit that allowed the estimate of the association between child outcomes and independent variables to vary by rater, while appropriately taking into account the correlation of child outcomes across the three raters. Specifically, we estimated the association between the child outcomes (emotional and behavioral problems on the BASC BSI and adaptive skills on the BASC ASC) and maternal depression and sociodemographic control variables separately for each rater. Multivariate Wald statistics, appropriate with GEE methodology (

49 ), were used to test whether the data supported the use of rater-specific associations for either maternal depression or for sociodemographic control variables. Simplified models were fit when associations were found not to vary across raters (Wald test p>.05), according to the mean of the associations for all raters. When associations varied by rater, we included rater-specific associations in the model. We then tested whether parenting and family environment characteristics mediated the association between maternal depression and children's outcomes by applying Baron and Kenny's (

50 ) and Kenny and Kashy's (

51 ) methodologies.