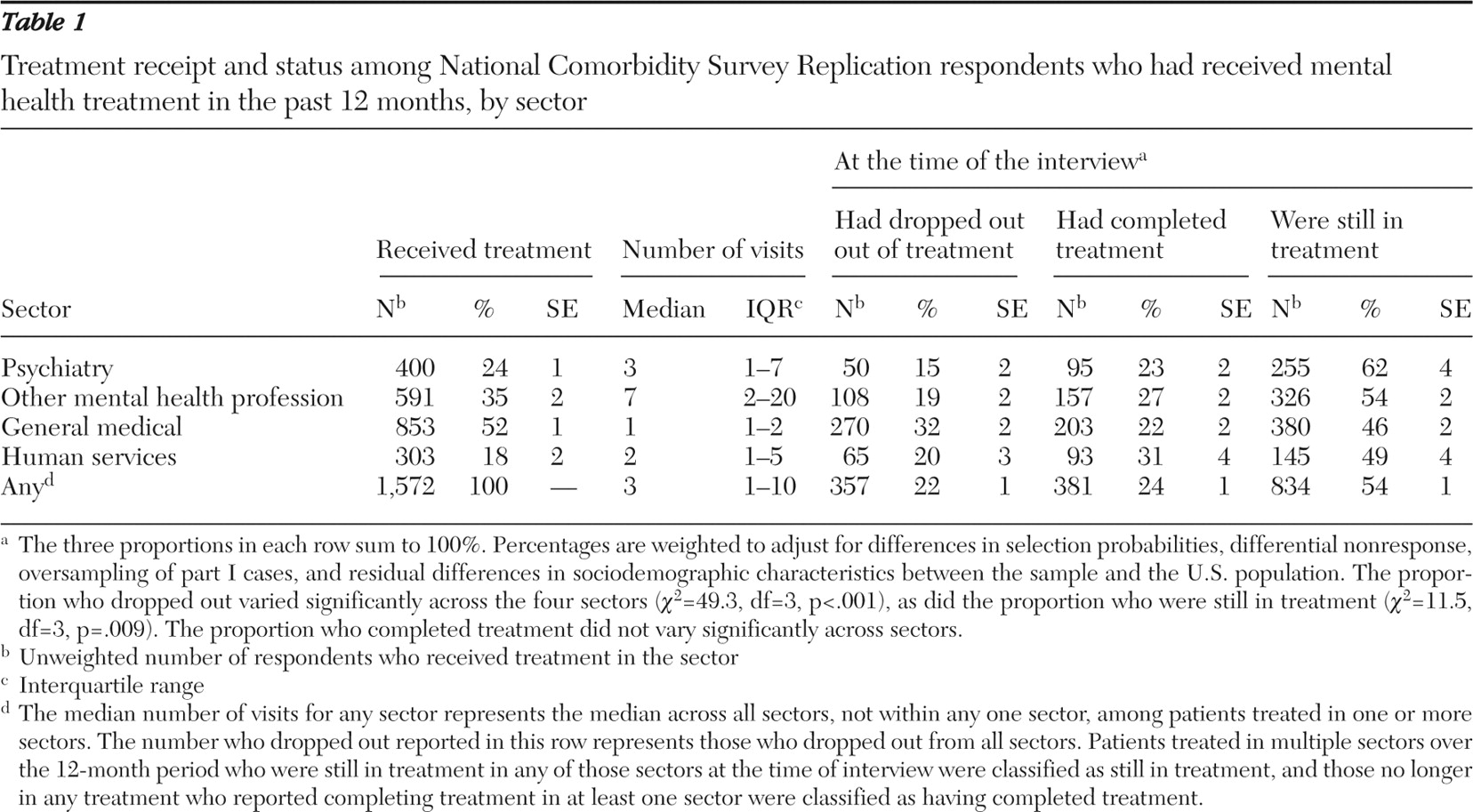

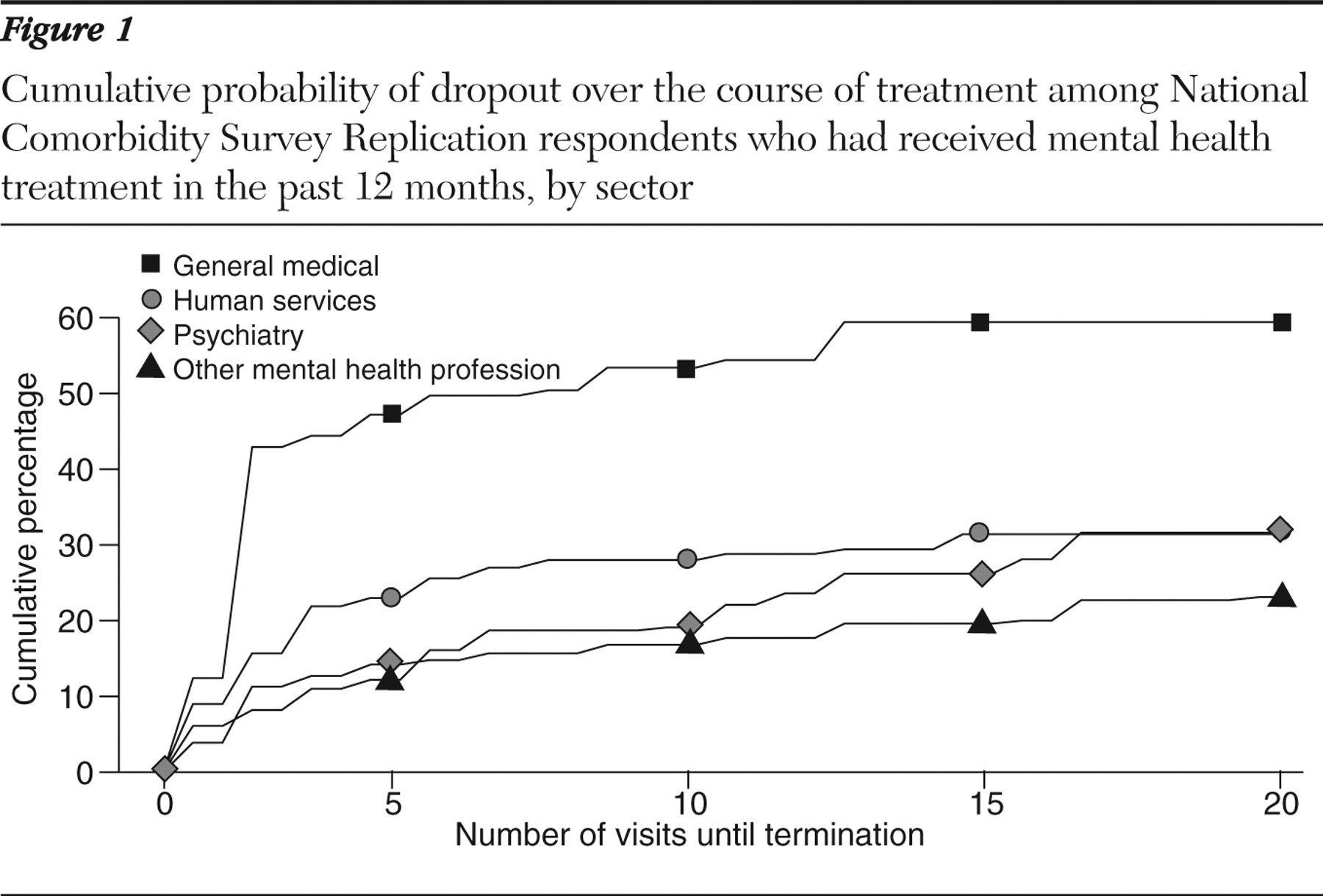

The overall services dropout rate (22.4%) resembles previous national estimates for the United States (19%) (

12 ) and Canada (17%–22%) (

1 ). In Canada lower dropout was found from care provided by primary care physicians than from care by psychiatrists or psychologists (

1 ). However, in this U.S. study, we found the highest dropout for the general medical sector. Compared with Americans, Canadians may have closer and more established relationships with their primary care providers. In the United States, the brevity of general medical visits (

20 ) offers little opportunity to develop patient rapport, trust, and participation (

21 ) and may contribute to risk of dropout. Although general medical care has traditionally been delivered by individual practitioners (

22 ), newer models involve collaborations between general medical and mental health professionals (

23,

24 ). The finding of lower rates of dropout among patients receiving care from multiple sectors supports the potential of this approach.

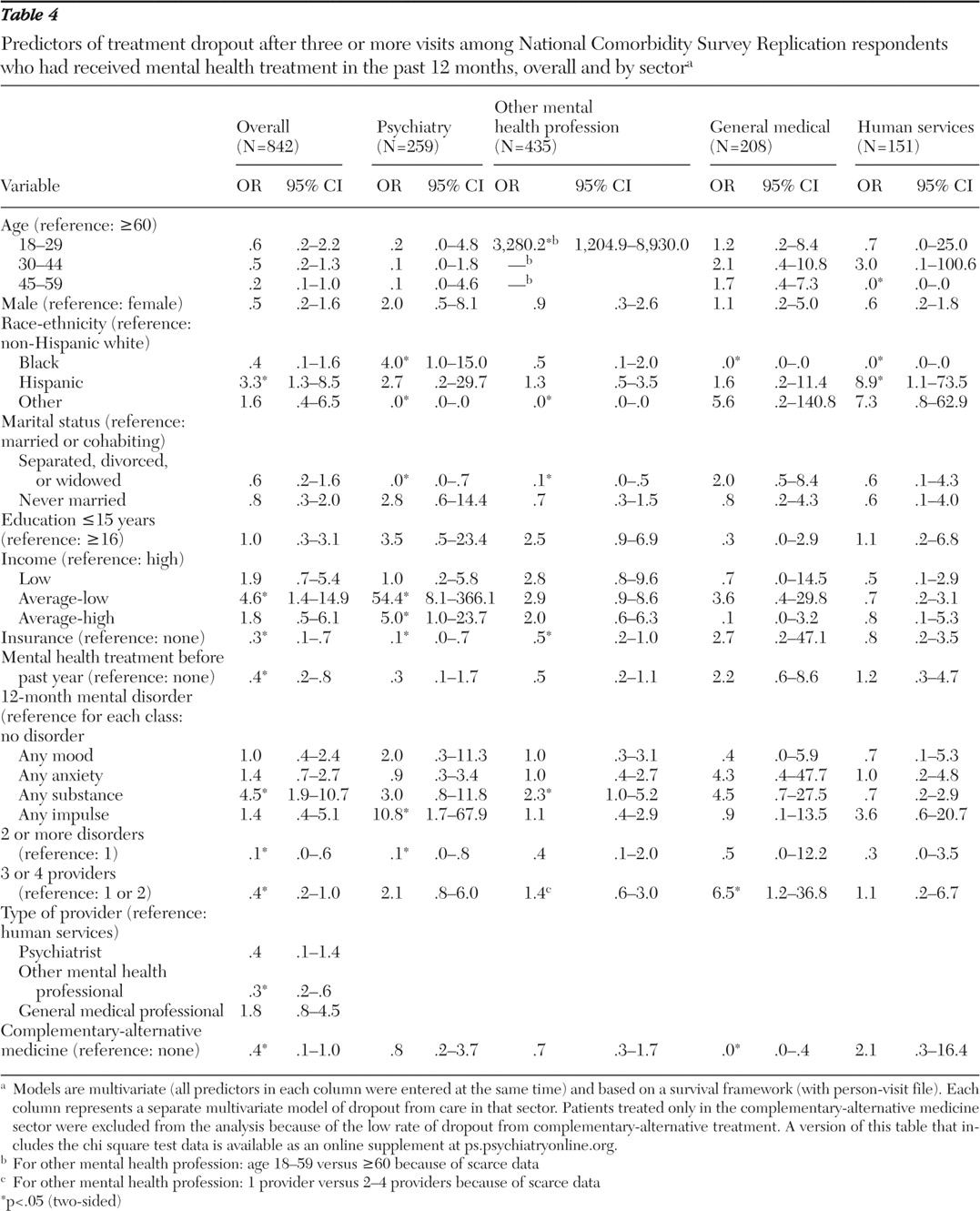

Risk factors for dropout

The behavioral model of access to health care (

25 ) offers one framework for organizing findings about client-level predictors of dropout. Under this framework, dropout risk can be viewed as a joint function of predisposing demographic factors (for example, gender and age) and social factors (for example, race-ethnicity, marital status, and education), enabling factors (for example, health insurance, income, and number of providers), and need (for example, psychiatric disorder, comorbidity, and past treatment). Below we review these factors, considering stage and sector of treatment.

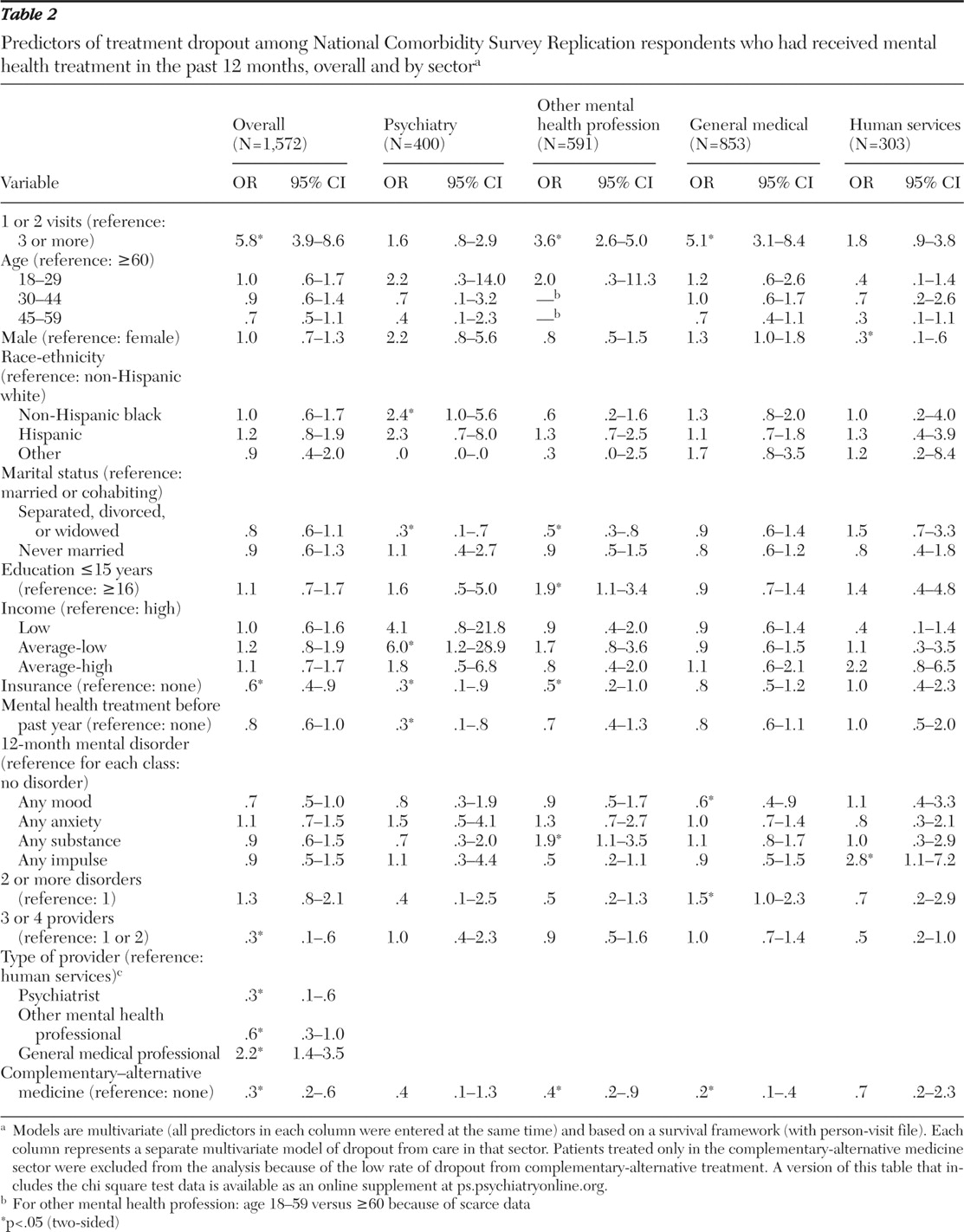

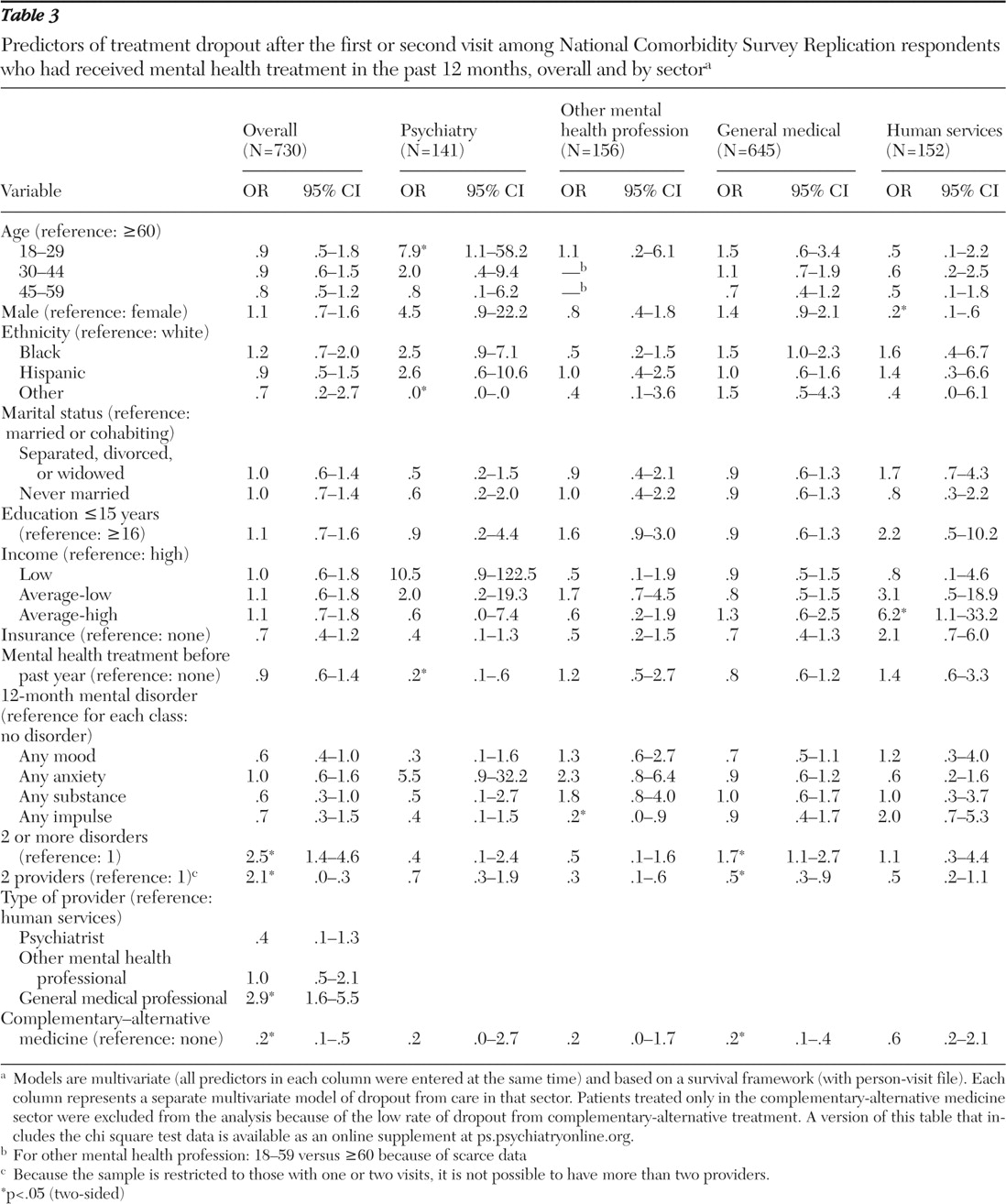

In keeping with NCS data (

12 ) and clinical research (

7 ), patient gender was not significantly related to overall risk of treatment dropout. However, women were significantly more likely than men to drop out early from treatment in the human services sector. The reasons for this are unclear, although this finding might be related to lower levels of illness severity among women compared with men who are treated in this sector. This gender difference in early dropout persisted despite adjustment for number and type of mental disorders. Patient age also was not significantly associated with overall dropout, although young age was associated with increased risk of early dropout from care provided by a psychiatrist (

12 ).

Aspects of social structure, including marital status, education, and race-ethnicity, had complex relationships with dropout risk. Compared with patients who were separated, divorced, or widowed, those who were married were significantly more likely to drop out from specialty mental health care later in treatment. This finding is in accord with evidence that spouses of patients receiving individual psychotherapy sometimes respond negatively to their partner's treatment (

26,

27,

28 ). Alternatively, patients without partners may tend to become more dependent on their psychotherapist and more likely to comply with treatment recommendations (

29 ).

Although education was not related to overall treatment dropout, 16 or more years of education was associated with a lower risk of dropout from care provided by mental health professionals other than psychiatrists. Acceptance (

30 ), utilization (

31 ), and completion (

32,

33 ) of psychotherapy have been directly linked to patients' level of education. Patients who have more education may also be more responsive to certain forms of psychotherapy (

34,

35 ).

Patient race-ethnicity had no overall association with odds of dropout. Non-Hispanic blacks, however, were significantly more likely than whites to drop out of care provided by a psychiatrist. Racial-ethnic differences in quality of mental health care (

36,

37 ) may contribute to racial-ethnic differences dropout.

Health insurance, higher income, and care coordination may enable service use and reduce dropout. The effect of health insurance in reducing dropout risk was evident after the first two visits, perhaps because having insurance lowers what otherwise would be mounting out-of-pocket treatment costs. The recent increase in uninsured Americans (

38 ) may increase the risk of dropping out of specialty mental health treatment. Similarly, high-income patients were less likely than patients with low-average incomes to drop out (

39 ), especially later in the course of care provided by a psychiatrist. Receiving mental health care from a larger number of provider sectors also reduced the probability of treatment dropout, but this could reflect a selection effect—more adherent or more assertive patients may be more apt to visit multiple sectors.

Use of complementary-alternative medicine was associated with a marked reduction in the odds of dropout from traditional mental health care services. These protective effects were greatest early in treatment. Self-help group attendance has been shown to enhance adherence to conventional mental health services (

40 ). Participation in self-help groups and other forms of complementary-alternative medicine has also been found to increase appreciation or satisfaction with mental health services (

41 ), which in turn may enhance retention in treatment (

42 ). Self-help groups tend to be used as supplements rather than alternatives to traditional care (

43 ). Our results raise the possibility that greater coordination of professional services with self-help and other complementary-alternative medicine services might help reduce dropout from professional care, a hypothesis that requires experimental evaluation.

Need—as measured by individual mental disorders, comorbid disorders, and past treatment—demonstrated complex relationships with risk of dropout. In the aggregate, substance use disorders were related to dropout after the first two visits, a finding consistent with reports of high dropout rates from specific substance abuse treatment programs (

44,

45,

46 ) and low perceived need for such treatment (

47 ). This is a particularly concerning finding, given that longer-term treatments tend to be more successful than brief treatments for substance use disorders (

48 ).

Overall, mood and anxiety disorders appeared to exert little influence on the propensity to drop out, although dropout from treatment provided in the general medical sector was significantly lower among respondents with mood disorders than without them. In evaluating dropout risk, consideration should be given to factors beyond measured clinical symptoms. Concepts such as predisposition to use services and enabling resources that have been primarily studied as predictors of service use (

25 ) may also guide assessment of treatment dropout risk.

Early in treatment, patients with comorbid psychiatric disorders were more likely than patients with one disorder to leave treatment delivered in the general medical sector, whereas later in treatment the reverse was true. General medical professionals likely have less experience managing patients with psychiatric comorbidities (

10,

49 ). Mismatches of clinical complexity and provider skill and resources may contribute to risk of treatment dropout.

Previous mental health treatment was linked to lower risk of dropout from care provided by a psychiatrist. This was observed early in such treatment and overall after two or more visits and is consistent with evidence that previous mental health service use tends to predict future use (

50 ). Stigma or embarrassment, which can contribute to treatment refusal or dropout (

51 ), may be more pronounced among new patients.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, because psychiatric disorders, service use, and treatment dropout were retrospectively assessed by self-report, the results are subject to recall bias. In community surveys, distressed respondents may tend to overstate the number of visits to a care provider (

52 ). Second, the duration of recommended treatment may vary between provider groups and among the providers within these groups, and patients' perceptions of providers' intentions introduce another level uncertainty. Third, treatment episodes were measured by number of visits. Provider groups may vary in the time between scheduled visits (

53 ), and treatment duration may be more important than number of visits (

54 ). Fourth, many potentially relevant patient characteristics (such as stigma, functional impairment, and satisfaction with treatment), professional characteristics (such as communication skills and clinical expertise), and service characteristics (such as copayments and environmental obstacles) were not examined. Fifth, the tendency of high service users to seek care from several sectors may explain their lower rate of dropout. Sixth, because a large number of comparisons were examined, some associations found to be significant may have occurred by chance. Seventh, the survey captured only visits from the most recent 12 months in what may have been long treatment episodes. However, because only 21% of all treatment episodes included more than 12 visits, it is unlikely that this truncation substantially influenced reported treatment dropout patterns. Finally, we were unable to account for aspects of care for the same episode occurring in the period before or after the 12-month reporting interval.