On the afternoon of May 13, 2000, a fireworks deposit situated in a residential area exploded, killing 22 people and injuring about 1,000 in the center of Enschede, a town in the east of the Netherlands. As a result approximately 1,500 houses were damaged, of which 498 had to be demolished, leading to displacement of 4,163 inhabitants (

1 ). An estimated 17,000 individuals were probably exposed in one way or another to this disaster (

1 ). The event was immediately declared a national disaster. In response, a nationwide support effort was launched and funds were allocated for research to document health consequences of this disaster. As a result, data about health, well-being, and medical service use have been systematically collected since the early days after this event (

2,

3,

4,

5 ).

Results

Between May 13, 2000, and June 1, 2004, there were 1,906 referrals to the specialized disaster team, consisting of 1,659 persons, including adults and children. On average, disaster-related referrals constituted 5.7% of the total number of referrals to the mental health care institute over the five-year period. The peak of disaster-related referrals occurred in the second year after the disaster (N=543, or 7.9% of all institute referrals). It is interesting that the overall number of referrals during the first year after the disaster dropped by nearly 20% compared with the previous year (1999), only to rise above baseline numbers in the second and third year. Especially high numbers of referrals were seen in month 24 (N=55) and month 32 (N=46) after the disaster. The first peak coincided with a claim procedure that started at month 24 after the disaster. The second peak occurred after an advertising campaign was launched to inform the general public that psychological support was available.

On the basis of the 1,659 referred persons and an estimate of 17,000 probably exposed inhabitants (

1 ), which included the 4,163 displaced persons, the four-year cumulative referral-incidence was 98 persons per 1,000 of the total exposed population (95% confidence interval=94–102). Of the 460 persons who initially accompanied an individual seeking treatment, 228 also received some form of treatment themselves, either in partner-relationship therapy (N=162) or individually (N=66). This group was not further examined in this study. Also not included were the 315 children who were referred to the service, 235 of whom (75%) received treatment, and 73 adults who were referred but who did not visit the center. This left a sample of 811 adult patients. [A flowchart showing the various groups is available as a supplement to this article at

ps.psychiatryonline.org .]

Of these 811 adult patients, 148 (18%) underwent only part of the intake procedure and did not enter treatment. A total of 663 adults entered treatment. Of the 663 patients, 211 (32%) dropped out very soon after intake; thus 452 adults (68%) entered the active treatment phase. In 95% of these cases (N=627), adequate information about the treatments provided could be extracted from the medical charts. For 548 patients (83%) the treatment algorithm was completed, and for 524 patients (79%) the chart information was sufficient to encode treatment outcome. In the assessment window between May 1, 2001, and June 1, 2004, a total of 394 persons completed eight or more sessions. Of these, 271 participated in the interview study (69%).

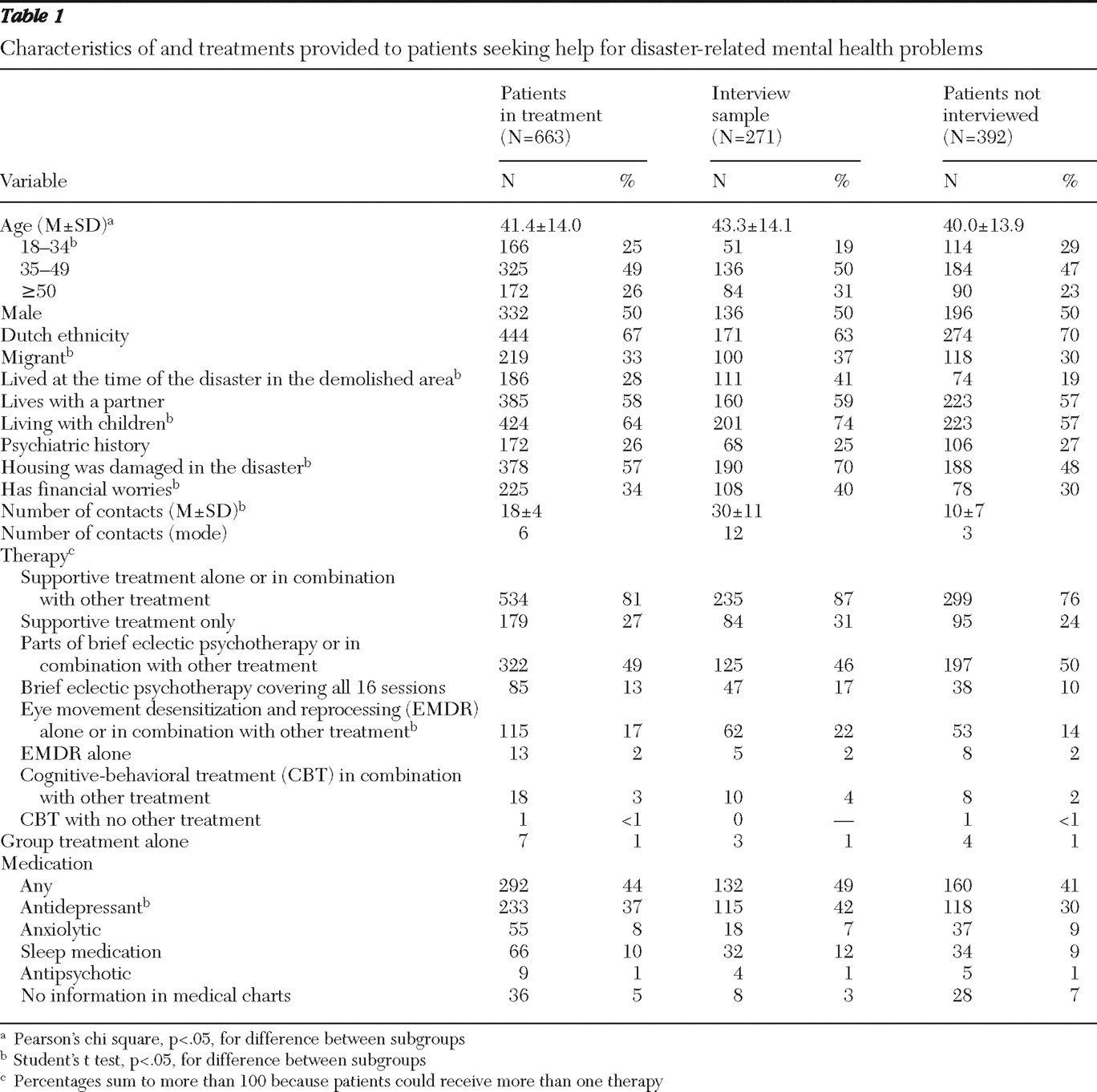

Table 1 provides data on demographic and diagnostic characteristics of and treatments provided to the 663 adult patients who entered treatment, as well as the 271 who participated in the interview study and the 392 who did not.

Compared with the group of patients who did not participate in the interview study, the interview group had fewer persons aged 18 to 34 years ( χ 2 =8.8, df=3, p<.025); in addition, the interview group had more migrants ( χ 2 =17.6, df=1, p<.001), more persons from the demolished area ( χ 2 =25.3, df=1, p<.001) or with demolished houses ( χ 2 =47.6, df=1, p<0.001), more persons living with children ( χ 2 =30.9, df=1, p<.001), and more persons with financial worries ( χ 2 =15.6, df=1, p<.001). Persons in the interview group were somewhat older (t=2.7, df=661, p<.05) and received far more treatment sessions (t=28.9, df=661, p<.001).

Supportive treatment, often in combination with other types of treatment, was the most common type of treatment used. Brief eclectic psychotherapy was the most common type of psychotherapy offered, which was the intent of the protocol. However, the protocol (that is, brief eclectic psychotherapy in 16 sessions) was completed with only 13% of the patients, and often it was combined with supportive treatment. Overall, two-thirds of the 663 patients received some form of psychotherapy—that is brief eclectic psychotherapy, CBT, or EMDR. Forty-four percent received medication. In most cases, the medications were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or other antidepressants (37%) or sleep medication (10%). For the variables shown in

Table 1, the proportions in the interview group were generally similar to those in the entire sample. However, a greater proportion of patients in the interview group than in the group that was not interviewed received EMDR (

χ 2 =21.3, df=1, p<.001) and antidepressants (

χ 2 =26.3, df=1, p<.001).

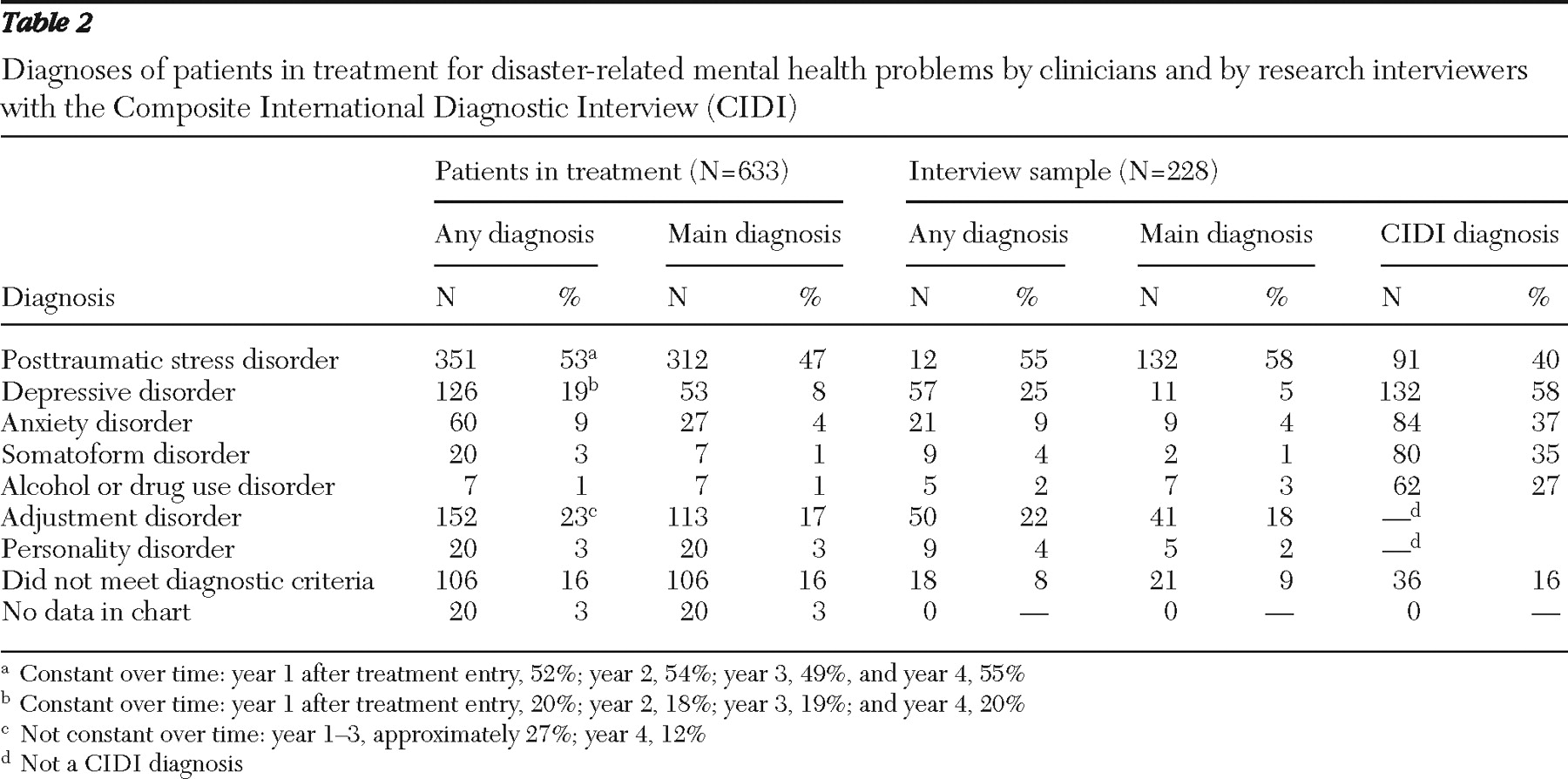

Table 2 shows the clinical diagnoses for the total sample and the interview group. For the latter, CIDI diagnoses are also reported. A CIDI was completed for 228 of the 271 interviewed patients (84%). In the total sample, PTSD was by far the most common clinical diagnosis (53%, with 47% having PTSD as the main diagnosis), followed by adjustment disorders (23%, with 17% as the main diagnosis) and depressive disorders (19%, with 8% as the main diagnosis). Sixteen percent of the patients did not meet criteria for any clinical diagnosis. For 3% of the patients, insufficient information was available in the chart. For the interview sample the picture was similar. Of interest, however, on the basis of the CIDI diagnoses, depressive disorder was the most common disorder (58%), followed by PTSD (40%). The largest discrepancies between the clinical and standardized diagnosis were seen for somatoform disorder (4% and 35%), anxiety disorders (9% and 37%), and substance use disorders (2% and 27%), indicating these diagnoses may have been missed.

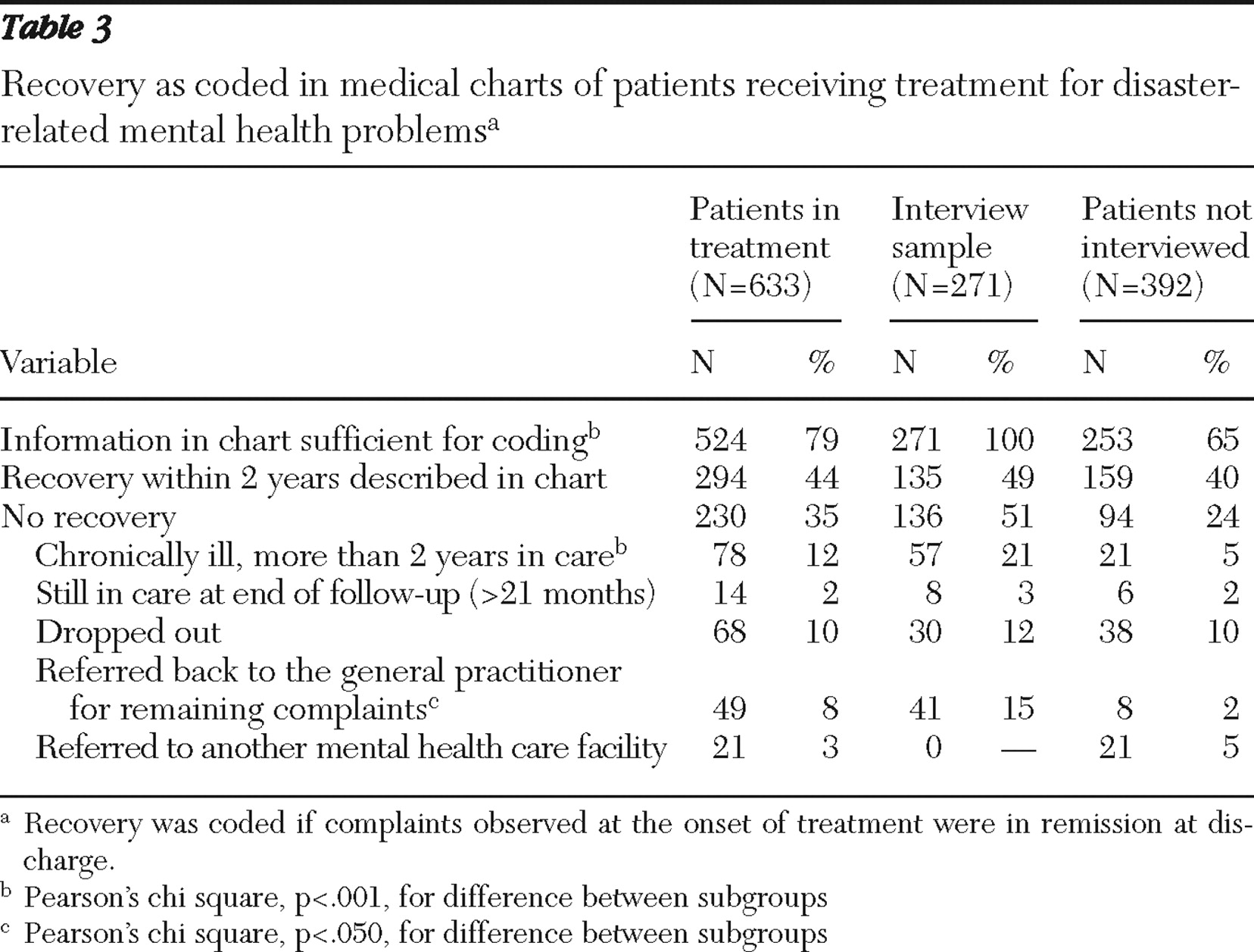

Table 3 presents information on recovery as recorded in the medical charts by clinicians. According to clinicians' chart notes, 294 of 524 patients recovered (56%, or 44% of the entire group). Of this entire group, 12% remained in care for more than two years, 8% were referred back to their family doctor, and 3% were referred to some other mental health program. In the interview group, clinically assessed improvement was reported for half of the patients (49%). Twenty-one percent continued after completion of the study, 15% were referred back to their family doctor, and 12% dropped out of treatment.

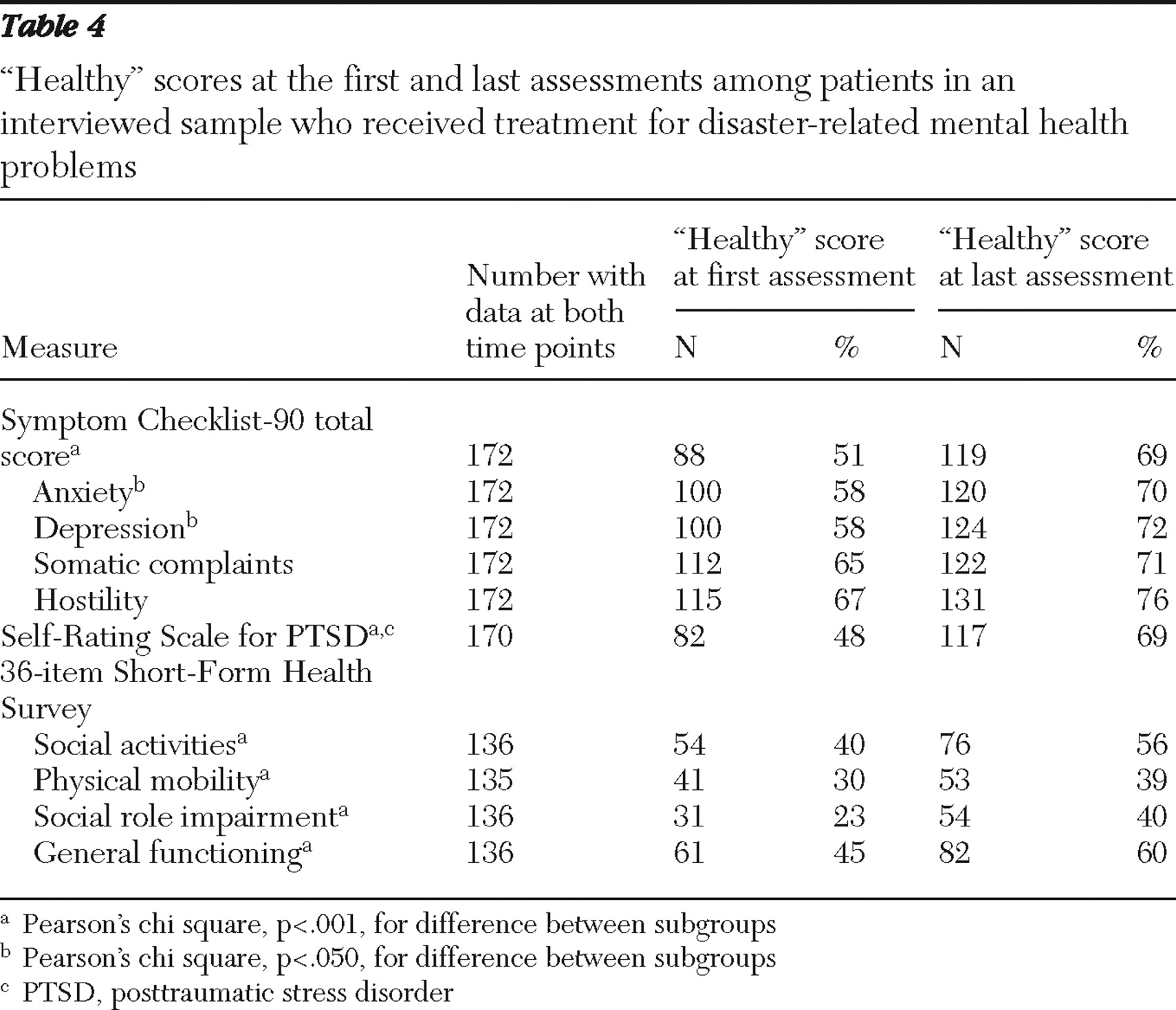

Table 4 presents information on patients judged "healthy" on the basis of questionnaire scores. On the basis of questionnaire data, most patients (between 56% and 76%) had a "healthy" score at last assessment on all items except physical mobility and social role impairment. On the SCL-90, patients showed statistically significant improvement on all measured outcomes except for the hostility and somatic complaints subscales.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to describe all persons who sought help at a specialized service for disaster-related mental health problems during four years after the devastating explosion of a fireworks deposit located in the center of Enschede, the Netherlands. To our knowledge few studies have documented the surplus incidence of psychopathology seen at mental health services after disasters. It is important to note that in the Netherlands these services are comprehensively covered by national insurance, and there were thus no financial barriers for anyone to visit the service. Other than primary care, no other services dealt with disaster-related problems, and other mental health services in the area directed people with these problems to the specialized service. The study thus provides a quite complete picture of all persons who sought help from mental health services for disaster-related problems in an affected region and describes the efficacy of mental health interventions in the real world under such circumstances.

This study is a relevant addition to the literature, which almost exclusively reports morbidity rates in the population at large (

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7 ) and results from treatment studies conducted under controlled conditions (

10,

11 ). This study showed that the extra influx of persons with mental health problems resulting from the disaster was limited in size; we found a four-year cumulative referral incidence of approximately 10% among the stricken population and an influx of disaster-related cases to the mental health services of 6% on average in the first five years after the event. This is a strikingly low figure compared with the estimations of 40% psychological morbidity in studies of disaster-stricken populations (

6,

7 ) and the estimated 30% in the Enschede population (

2 ). Apparently, help-seeking behavior and referrals by general practitioners to mental health services for disaster-related mental health problems were relatively low (

5,

6,

7,

8,

9 ).

We observed a recovery rate of approximately 50% on the basis of clinicians' reports, between 69% and 76% in symptoms, and between 39% and 60% in social and physical functioning on the basis of "healthy" scores at the final assessment. Even though these changes were all statistically significant, arguably the differences in scores between first and last measurement are modest. Recovery in terms of improved social function and physical mobility appears to have been less robust.

The study has several shortcomings. First, very little information is available about the persons who were seeking care in the first few months immediately after the disaster. During this period the registration system was not yet fully operational, and we have incomplete information about those who came to the service at that time. There is evidence that in the early days after the disaster many victims contacted their general practitioner (

3,

5 ).

A second shortcoming is the fact that only clinical information based on case notes is available for most of the patients. This source of information is notoriously incomplete and inconsistent at times. We were able to gather more in-depth material using standardized methods for only a much smaller group of patients—that is, those who received substantial treatment for disaster-related pathology. This limitation resulted from a decision made early in the study that provision of treatment should prevail over research interests and that patients would probably be more willing to participate in research once they had started actual treatment. Our response rate for the interview study was 69%, which is considerably higher than the 54% reported by Weisaeth (

12 ). As a result of this decision the interviewed sample differed in several demographic and clinical characteristics. Also, the fairly high percentages of "healthy" scores at the onset of the questionnaire study and the relatively small difference in scores between first and last measurements are probably the result of late first assessments.

It should be noted, however, that the interview sample did not differ substantially from the total group of patients in clinical diagnoses, received treatments, and overall clinical outcomes. We believe, therefore, that the combination of case notes and questionnaires provided a fairly complete picture of service involvement in the aftermath of the disaster. The added value of the standardized assessment in the interview study is particularly clear for the diagnostic information; CIDI diagnoses indicated that disorders other than PTSD were quite common—and far more common than clinician diagnoses indicated. However, it must be noted that the CIDI interview took place several weeks after the clinical interview. Despite late assessment, the extent of the differences in our results seems to indicate that clinicians in this specialized service may have been focusing too much on PTSD and may have overlooked the presence of depression, anxiety, substance use disorders, and somatoform disorders. As a consequence, treatments were also largely oriented toward PTSD. It seems reasonable to assume that with a more accurate diagnosis and adequate treatment based on this diagnosis, better overall treatment results could have been achieved.