A long-standing operating principle of assertive community treatment (ACT) is that services should be time unlimited. The Dartmouth ACT fidelity scale lists long-term service delivery as a fidelity indicator, such that the highest score on this item is for programs that provide services indefinitely (

1 ). The principle of "continuous long-term service" originated with research findings that even after 14 months of treatment, participants who terminated experienced subsequent clinical deterioration and increased hospitalization (

2 ). However, the assumption that such services should be time unlimited may limit access to ACT, because staff resources may remain committed to clients who can successfully transition to other services. Despite the continuing evolution of community practices for people with severe mental illnesses, there have been no recent studies supporting time-unlimited service delivery, and a small number suggest that safe transitions are possible (

3,

4,

5 ).

We are unaware of publications that have presented basic information on the proportions of patients who discontinue ACT treatment either early in treatment or after more extensive involvement or on clinical correlates of early or late termination. It is unclear whether persons who terminate from treatment have more or less severe problems, make more or less use of services initially, or show clinical improvement or deterioration. Further consideration of this long-standing ACT practice of time-unlimited treatment would require data on postdischarge outcomes, but the design of such studies would be informed by descriptive data on the natural process of termination.

Since 1987 the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) has developed a large national program based on the ACT model. This program, referred to as Mental Health Intensive Case Management (MHICM), currently serves over 7,000 veterans annually. The MHICM program conforms to the ACT program criteria pertaining to human resources, organizational boundaries, service delivery, and substance abuse treatment (

6 ). We used administrative data from the MHICM program to compare experiences of veterans who terminated services before one year or between one and three years of admission with those of veterans who continued beyond three years. Through these comparisons we seek to present basic descriptive information on a little-studied but potentially important aspect of ACT.

Methods

The MHICM program

The MHICM program serves veterans with severe and persistent mental illness and significant functional impairment who are inadequately served by standard outpatient care and who typically have high past levels of hospital use. MHICM services are intended to follow the ACT model (

6,

7 ).

Data sources

In this study we included veterans enrolled in the MHICM program from FY 2002 to FY 2004 who had complete baseline and service delivery forms during the first six months of participation (N=1,402). Sociodemographic characteristics, diagnoses, clinical status, and community adjustment were documented on standardized forms completed at the time of admission. Data on patterns of service delivery were obtained from structured semiannual summaries completed by MHICM staff for each veteran after six months of participation, at the time of termination, or both. Termination was documented by clinicians at the time it occurred, and such data were available through the end of FY 2007, ensuring at least three years of potential participation. A veteran is considered to have terminated (and case managers complete a termination documentation form) when a veteran is judged to no longer need intensive case management, when all efforts to engage a veteran in the program have failed, when the veteran has moved out of the team's catchment area, or when he or she is placed in a long-term care facility, such as a nursing home. In this article termination thus refers to a clinical judgment by the case manager that the veteran will no longer be participating in the program for any one of several reasons. It does not preclude future participation, nor does it reflect the source of the decision (case manager, veteran, or some other party). It is entirely an indicator of present expectation of future behavior. Once a veteran has terminated from the program, all MHICM services discontinue and a new referral is required to reenter the program.

Detailed reasons for termination were not documented during the period covered by this study, but the clinicians' impression of reasons for termination was coded for a limited number of categories after FY 2005 (for example, moved away, did not need further treatment, moved to nursing home or other institution, was uncooperative, or refused services despite clinicians' concerted efforts to engage the veteran). Veterans who died were excluded from the analyses presented here.

Additionally, an outcome assessment was completed after six months, allowing comparison of clinical change for a subset of participants for whom data were available (N=913, 65%). The institutional review boards of the VA Connecticut Healthcare system and Yale Medical School approved this study.

Measures

Sociodemographic measures documented age, gender, race, education, marital status, employment, income, disability status, and assignment to a payee or fiduciary to manage the veteran's finances. Clinical measures included the diagnosis assigned by the treating clinician at the time of enrollment. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (

8 ) was used to measure symptom severity, and the Brief Symptom Index (BSI) Global Severity Index (GSI) (

9 ) was used to measure subjective distress. Selected questions from the Addiction Severity Index documented alcohol and drug use in the previous 30 days (

10 ). Lifetime duration of both VA and non-VA psychiatric hospitalizations was also coded. Additionally, self-reported rating scales were used to assess suicidality (range 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more serious suicidality—for example, requiring hospital care) and violence (range 0 to 5, with higher scores indicating more violent behavior) (

11 ) in the 30 days before enrolling in the program and at follow-up.

Community adjustment was evaluated with the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) (

12 ), and selected items from the Lehman Quality of Life Inventory (

13 ) assessed satisfaction with life in general, with living arrangements, with friendships, and with family relationships. Role functioning was assessed with the Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) (

14 ). Veterans were also asked whether they had been arrested or spent a night in jail for any reason during the previous six months.

To assess treatment processes, case managers completed semiannual structured summaries of MHICM services provided to each veteran. We present information from the first of these assessments documenting the frequency of face-to-face contacts with the veteran in the community (scored from 1, once a month or less, to 5, three times per week); the percentage of face-to-face contacts that took place in the community (scored as 1, 0%–20%; to 5, 81%–100%); total time spent with the veteran weekly (1, less than 30 minutes per week, to 5, more than 120 minutes per week); and both distance from MHICM staff offices to the veteran's home (1, less than one mile, to 8, greater than 50 miles) and travel time from MHICM staff offices to the veteran's home (1, less than one minute, to 6, more than 60 minutes to drive).

General types of services that were provided during the six-month period (for example, rehabilitation, psychotherapy, crisis intervention, management of psychiatric medications, screening for medical problems, and provision of substance abuse treatment, housing, and vocational support) were documented with a series of dichotomous variables. Case manager and veteran ratings of therapeutic alliance were assessed using a 7-point Likert scale with questions about the nature of the clinical relationship adapted from the Working Alliance Inventory (

15 ). Participants were also asked to rate their general satisfaction with VA mental health services.

Clinicians were required to document termination when it occurred, using a structured progress report. Termination was said to have occurred when all efforts to engage the veteran had failed or when the veteran moved or was placed in a long-term care facility, such as a nursing home, or expressed a desire to discontinue this service. Reasons for termination have been documented since FY 2005 and thus are available only for more recent samples.

Analysis

We compared sociodemographic characteristics, clinical characteristics, and community adjustment of MHICM clients who terminated early (before one year), who terminated later (one to three years), and who did not terminate during the study period (more than three years). Chi square analysis was used to test the significance of differences in categorical measures, and analysis of variance was used for continuous variables. To decrease risk of spurious associations because of the large number of variables and sample size, the level of statistical significance for bivariate comparisons was set at p<.01. Analysis of covariance was used to compare six-month outcomes with adjustment for baseline values of each outcome to assess short-term clinical changes.

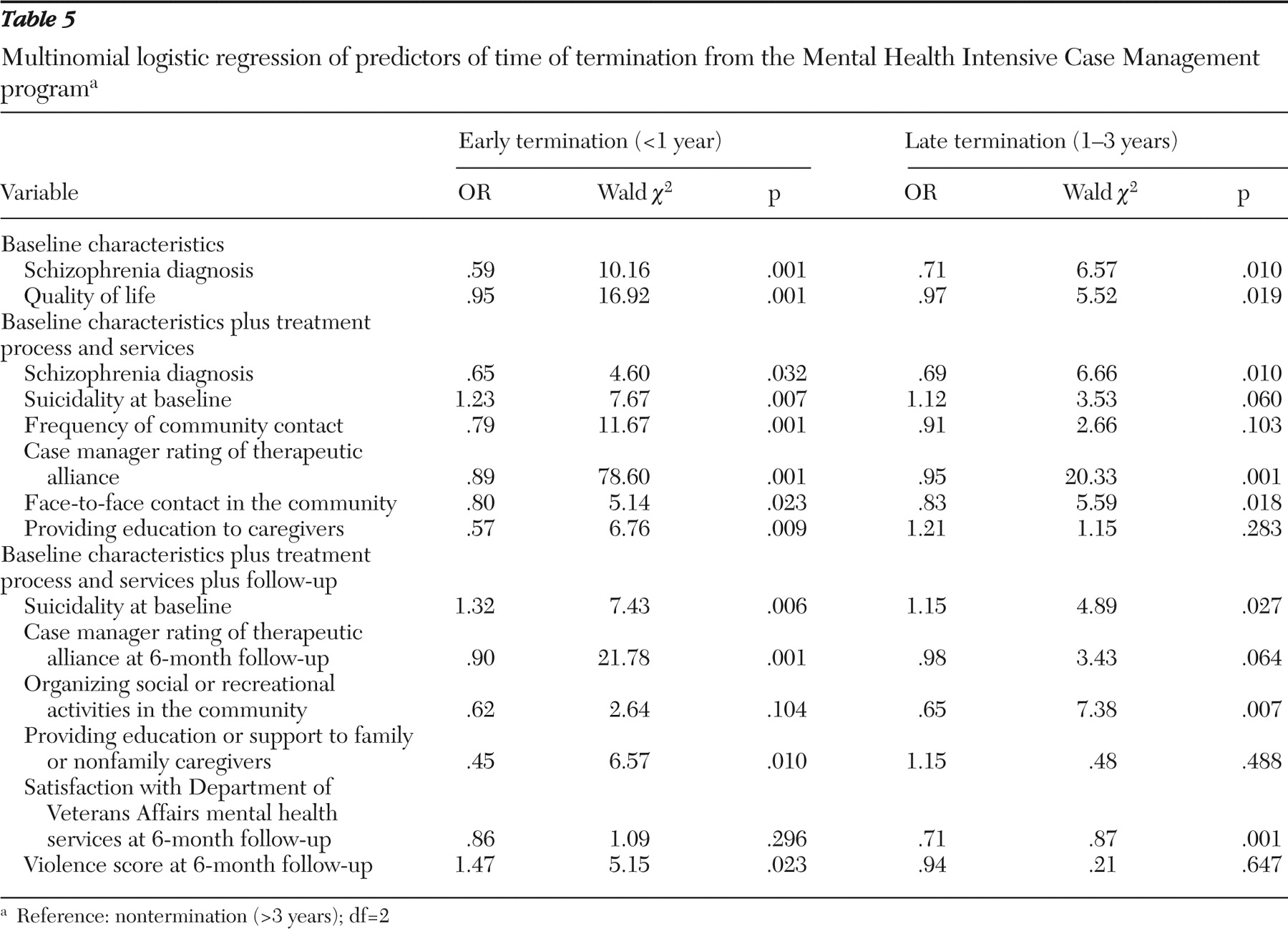

Multinomial logistic regression was used to identify independent baseline characteristics, measures of service use, and six-month outcome data that were significantly different among veterans with early or later termination compared with those who had not terminated after three years. Because baseline data were available on more participants than were data on treatment processes and on early outcome, three separate multivariate models were evaluated: one focusing on baseline characteristics alone, another focusing on both baseline characteristics and service delivery processes, and a third focusing on baseline characteristics, treatment processes, and six-month outcome measures. Measures that were significantly different between groups on bivariate analysis at p<.01 were included in the three stepwise multinomial logistic regression models. These models generated two parameter estimates for each independent variable: one for participants who terminated early versus those who did not terminate, and one for participants who terminated later versus those who did not terminate. Level of statistical significance for these analyses was set at a traditional p<.05, because a smaller number of measures were included.

Finally, for program participants who had data available concerning reasons for termination, chi square tests were used to compare the reasons for termination between veterans who terminated treatment before one year and those who terminated between one and three years.

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

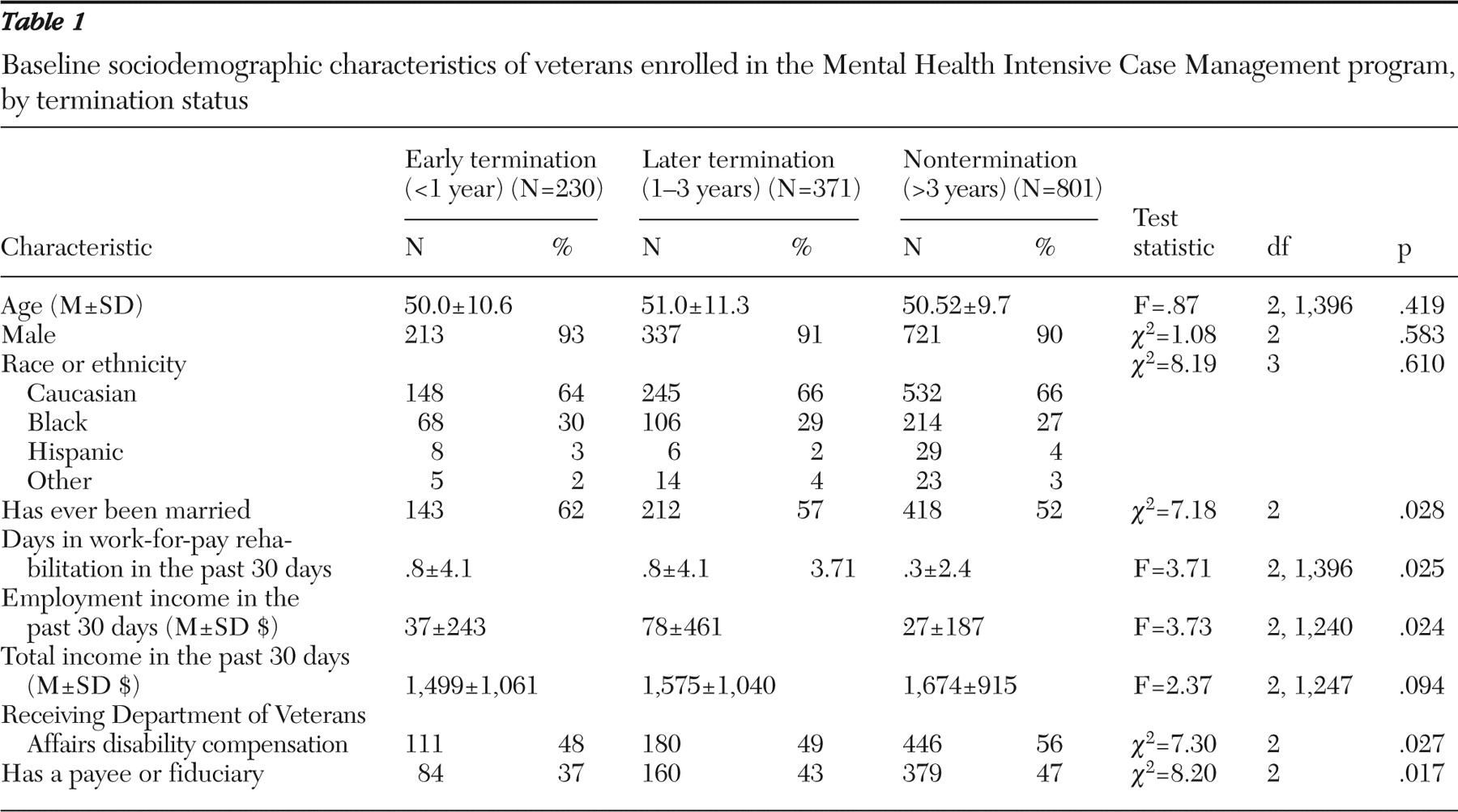

Of the 1,402 veterans enrolled in MHICM between 2002 and 2004, 16% terminated before one year (early), 26% terminated from one to three years (later), and 57% had not terminated after three years. Participants in these three groups did not differ significantly on any of the sociodemographic characteristics examined (

Table 1 ).

Clinical characteristics and community adjustment

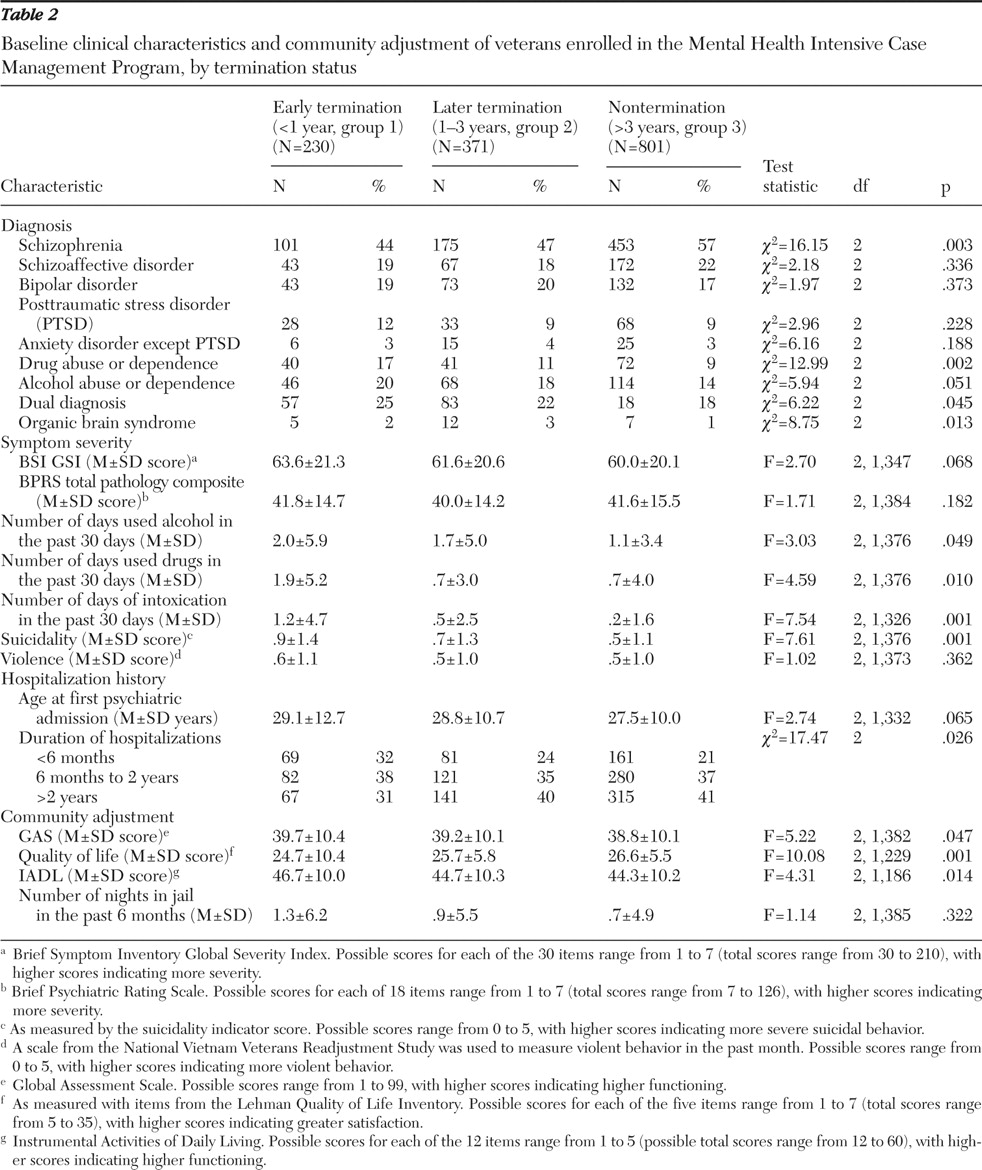

Veterans who terminated early were the least likely to be diagnosed as having schizophrenia (44%), followed by veterans who terminated later (47%), and those who did not terminate (57%) (p=.003). The reverse pattern was found for diagnoses of drug use disorder: participants who terminated early were the most likely to have diagnoses of drug use disorder (17%), followed by participants who terminated later (11%) and those who did not terminate (9%) (p=.002). Veterans who terminated before the first year also had significantly higher suicidality scores, compared with those who never terminated (p<.001) (

Table 2 ). On measures of quality of life, clients who terminated early scored slightly but significantly lower than those who never terminated (p=.001). In contrast, clients who terminated early scored slightly higher on IADLs than those who never terminated (p=.01, for paired comparison). Thus, although there were no significant differences between the three groups on most sociodemographic or clinical characteristics and although the sample overall showed high rates of psychosis and disability, those who terminated early had more serious problems than those who did not terminate, as evidenced by drug abuse diagnoses, suicidality, and poorer quality of life, but they had lower rates of schizophrenia and higher IADL scores, indicating better functioning (

Table 2 ).

MHICM treatment process and services

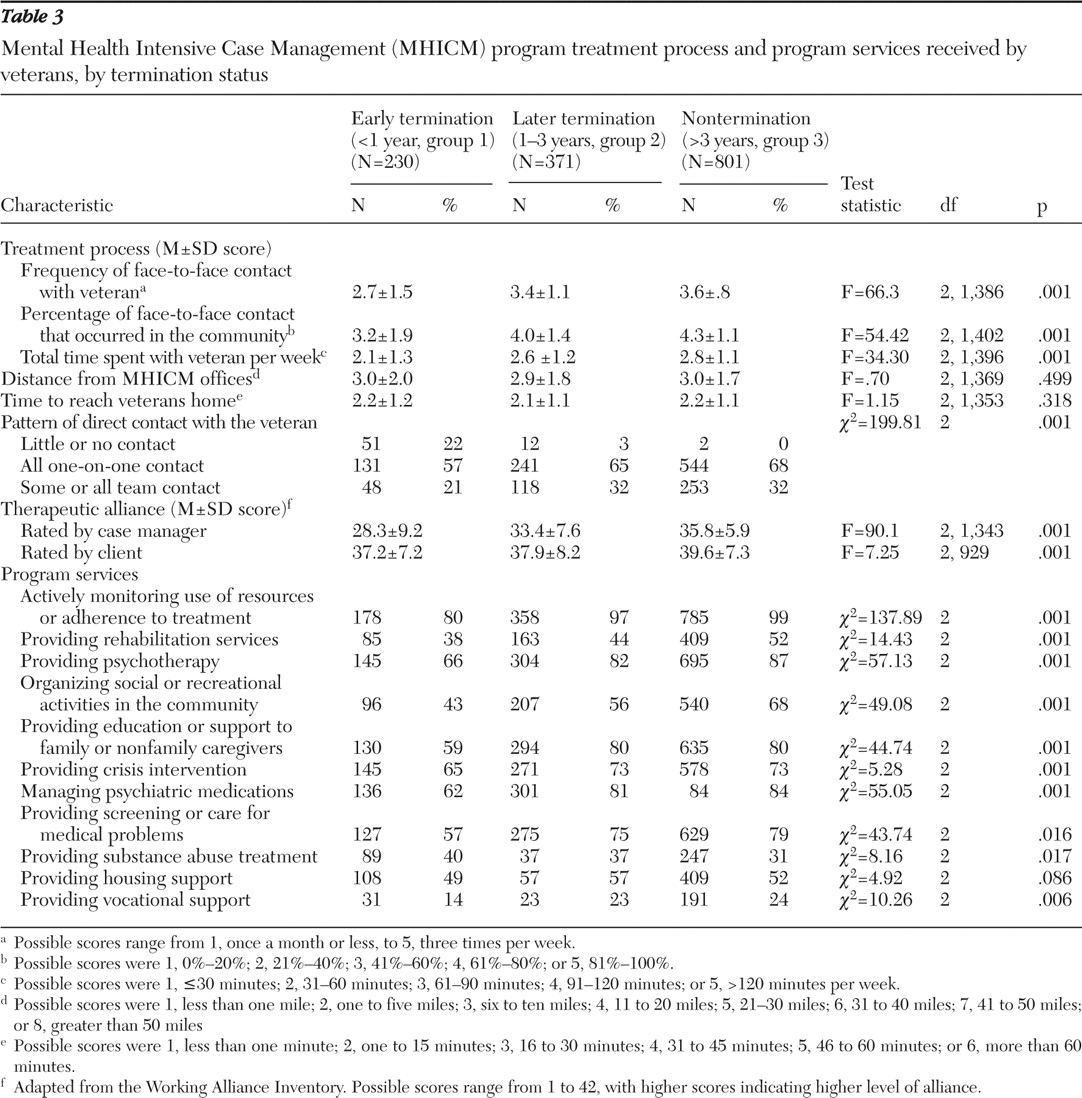

Veterans who terminated from services before one year were seen substantially less frequently, had a lower proportion of face-to-face contacts in community settings, and spent less total time with their case managers, compared with those who terminated from one to three years, who in turn had less frequent contact than clients who had not terminated after three years (p=.001 for all) (

Table 3 ). Compared with veterans who had not terminated after three years, veterans in the two termination groups had slightly but significantly lower client therapeutic alliance ratings at follow-up. However, case manager therapeutic alliance ratings were far lower for veterans who terminated early than for either those who terminated later or those who did not terminate; case manager therapeutic alliance ratings were significantly lower for those who terminated later than among for who did not terminate, although the magnitude of the latter difference was considerably smaller (

Table 3 ).

Significantly smaller proportions of veterans in the early and later termination groups received psychotherapy and screening for medical problems. Significantly smaller proportions of veterans in the early termination group received education and support for family members or caregivers (

Table 3 ).

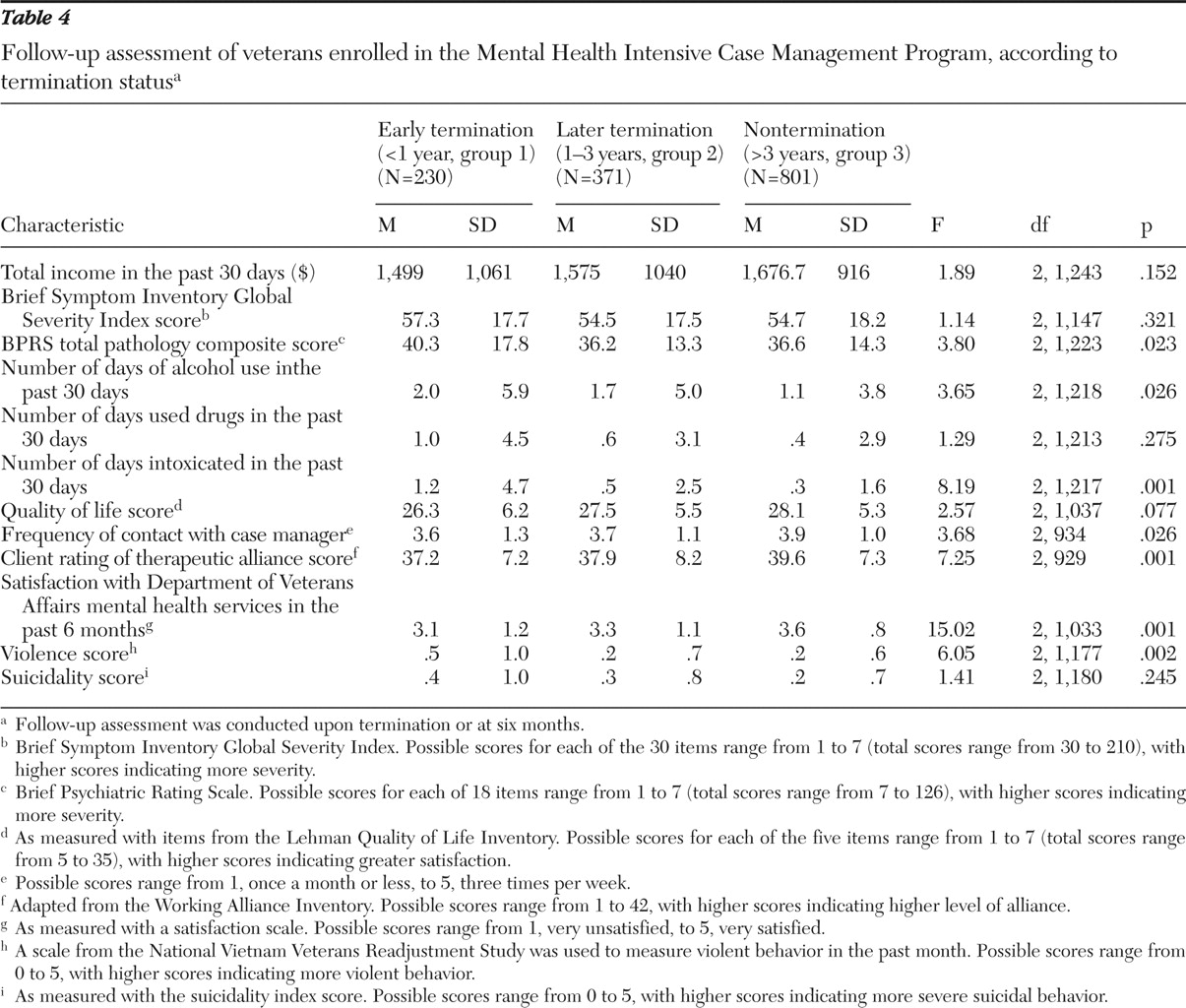

At follow-up, participants who had not terminated after three years rated their satisfaction with VA mental health services higher than either of the groups who terminated. Participants who terminated earlier also had higher follow-up violence scores and spent more days intoxicated than either the group who terminated later or those who had not terminated after three years (

Table 4 ). There were no significant differences on any other early outcome measures, even after analyses controlled for baseline values of these measures.

Multinomial logistic regression

The model including only baseline characteristics showed that patients who terminated before the first year or from one to three years were substantially less likely to be diagnosed as having schizophrenia and had higher quality-of-life scores, compared with those who had not terminated after three years (

Table 5 ).

When we examined the model including data on baseline characteristics and service delivery processes, we found that patients diagnosed as having schizophrenia were less likely than those without such a diagnosis to have terminated, which was also seen in the first model. Much like the findings in bivariate analysis, multinomial logistic regression showed that veterans with higher ratings on the suicidality scale were also significantly more likely to have terminated. The strongest predictors of termination using the magnitude of the overall Wald chi square as an indicator were measures of participation during the first six months. Discharge before one year was associated with less frequent clinical contacts, a lower proportion of contacts in the community, lower therapeutic alliance ratings by the case manager, and a lower likelihood that caregivers received educational services. Termination from one to three years, in contrast, was significantly associated only with the case manager rating of therapeutic alliance and less frequent face-to-face contacts.

When we added six-month outcome data to the models including baseline characteristics and service delivery processes, again participants who had higher suicidality scores at baseline were more likely to terminate. As in previous analyses, the stronger the case manager ratings of therapeutic alliance and the more frequently education and support were provided to caregivers, the less likely participants were to terminate before one year. Compared with veterans who had not terminated after three years, those who terminated from one to three years reported decreased likelihood of participating in social and recreational activities offered by MHICM teams and lower general satisfaction with VA mental health services at follow-up. It is especially notable that a higher rating of violent behavior was the only outcome measure significantly associated with termination and only with increased likelihood of termination in the first year (

Table 5 ).

Reasons for termination

Data on reasons for termination were available for veterans surveyed after FY 2005 (N=557). In this group, 153 (27%) terminated early, and 404 (73%) terminated later. Comparison of case manager reports of the reasons for termination (for example, moved away, accomplished the goals of the program, placement in a nursing home, uncooperative or refused services, and other) between those who terminated early and those who terminated later showed that those who terminated early were more likely to have been reported to have moved away from the area in which the program was located (62 persons who terminated early, or 41%, versus 95 persons who terminated later, or 23%) (p=.001). Those who terminated later were more likely to have been regarded by their case managers as having accomplished the goals of the program (12 persons who terminated early, or 8%, versus 104 persons who terminated later, or 26%). The proportions of veterans who were reported to have been uncooperative or refused service were not significantly different between participants who terminated early and those who terminated later (55 persons who terminated early, or 36%, versus 128 persons who terminated later, or 31%).

Discussion

Using administrative data for 1,402 veterans entering a national VA program modeled on ACT, we found that almost half terminated within three years: 16% before one year, and 26% from one to three years. It is notable that for the majority of baseline clinical characteristics, there were no significant differences between veterans who terminated and those who did not. Veterans who terminated, whether before the first year or later, did not differ on most measures from those who had not terminated after three years. Veterans who terminated from the program, either early or later, were less likely than those who did not terminate to be diagnosed as having schizophrenia, suggesting that the program is successful in retaining patients with severe psychiatric illness (

5 ). On the other hand a greater proportion of those who terminated within one year were significantly more likely to have diagnoses of drug use disorder at the time of enrollment, a lower quality of life, and higher suicide scores. These factors might have made these patients more difficult to assist but also may have indicated that they were in greater need of intensive services. It is widely believed that persons with substance abuse problems, in particular, are best treated in integrated dual-diagnosis programs with specific substance abuse expertise on the case management team (

16,

17,

18 ). Such expertise is not built into most MHICM programs. These associational data, although not demonstrating definitive causal relationships, may point to a need for further investigations into how to better meet the needs of this small but vulnerable population and to explore ways to provide substance abuse training to the MHICM staff.

When treatment processes and services provided by MHICM teams were considered in addition to baseline characteristics, the most robust predictor of termination was a lower case manager rating of the therapeutic alliance. It is especially notable that although the veteran's view of the therapeutic alliance was significantly associated with retention in the bivariate analysis, it was not significant when entered in the same model with the case manager therapeutic alliance rating. It thus appears that both for early and later termination the level of comfort and perceived efficacy that the individual case manager felt with the client was more strongly associated with continuing treatment than all other factors. Other measures that appeared to predict termination more robustly than baseline characteristics reflected lower intensity of service delivery. It is unclear whether more intensive participation early in the program reflected greater assertiveness on the part of program staff in engaging certain patients, greater interest in participating in intensive services by veterans themselves, or both. In either case it seems likely that more intensive participation reflected some degree of patient preference.

In the model including early outcome assessments, two measures emerged as significant independent predictors. General satisfaction with VA mental health services was lower in the group that terminated from one to three years than in the group that did not terminate after three years, but it was not significantly different between those who terminated before one year and those who did not terminate. A greater level of violent behavior at follow-up was the only clinical measure that showed an independent association with early termination, perhaps because such behavior led the staff to feel unsafe, although it is also possible that such veterans entered inpatient or residential treatment.

Although it is important to note that there were no significant differences on most baseline or early outcome measures, case managers may have felt that MHICM services were either not appropriate or not likely to be effective for veterans with severe behavioral problems, such as suicidality or violence. Alternatively, these veterans themselves may have preferred different forms of treatment.

Data on case managers' impressions of the reasons for termination, however, suggest that uncooperativeness or refusal of services, although the most common reasons overall, were no more frequent among patients who terminated before the first year of treatment than among those who terminated from one to three years. Compared with veterans who terminated from one to three years, those who terminated before the first year were more likely to be reported to have moved away and less likely to have terminated because they had achieved their personal goals and had less need of the program. Thus consumer life choices may be more important determinants of early termination, whereas achievement of appropriate goals was more important in later termination.

Several limitations of this study require comment. The most notable is the lack of follow-up data on symptom severity and hospitalization after termination and the fact that the six-month outcome data were missing for many veterans. Future studies should focus on obtaining posttermination outcome data and including comparison groups wherever possible. Ultimately our results are mixed, suggesting that patients who appear more vulnerable on some measures may have been more likely to terminate involvement in the program but that case manager skill in engaging clients may be a more important factor. However, it should be acknowledged that the descriptive data presented here raise the possibility that clients who terminate early are less well served, but they do not unequivocally support the conclusion that they are less well served. These data show that lower service use may have prompted early termination rather than caused it. As stated in the introduction it is widely believed that ACT patients should be offered time-unlimited treatment, but this assertion is based on limited and quite old data. The goal of our study was to describe what actually happens in a large ACT-like program. In the absence of outcome data and data from an appropriate comparison group, a determination of whether early termination represents either poor service delivery or poor responsiveness to individual patient preferences cannot be made.

It should also be noted that we conducted numerous comparisons without adjusting our threshold level of statistical significance (p<.01) for the large number of comparisons, because this study is descriptive in nature and did not test a hypothesis related to a single primary outcome. This study clearly demonstrates that termination from ACT-based service is not uncommon, is primarily associated with lower intensity of initial service use, and is deserving of further research and clinical consideration.