Results from 14 empirical studies are organized according to the effects of language proficiency and interpreter use on three outcomes: psychiatric assessment and diagnosis (most studies), treatment, and patient-provider interaction.

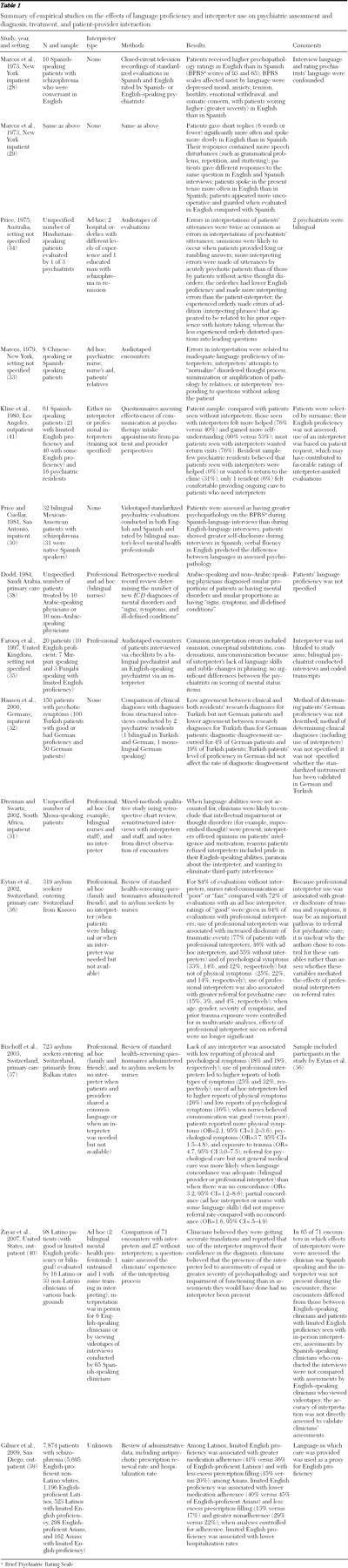

Table 1 shows the studies chronologically. When possible, results are presented separately for patients seen with or without interpreters or by bilingual providers; however, some studies provided insufficient information, and not all of these categories are represented in the literature. Ad hoc interpreters included anyone facilitating translation who was not trained in medical interpreting, such as bilingual hospital staff; friends or family, including minors; and other patients.

Psychiatric assessment and diagnosis

Four small-scale studies demonstrated that psychiatric assessment may be compromised among patients who are seen without interpreters (

28,

29,

30,

31 ). In South Africa, clinicians interviewing Xhosa-speaking inpatients without interpreters tended to use closed-ended questions and elicit brief replies, subsequently concluding that patients lacked intellectual capacity or that they had impoverished thoughts (

31 ).

Studies of standardized evaluations of Spanish-speaking inpatients with schizophrenia that were conducted both in English (without interpreters) and in Spanish reported contradictory findings in overall scores on the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (

28,

29,

30 ). Marcos and colleagues (

28 ) found higher BPRS scores among patients assessed in English than among those assessed in Spanish, whereas Price and Cuellar (

30 ) reported lower scores among those assessed in English. Several factors may have contributed to this discrepancy. Patients' responses to some questions differed in each language—for example, they endorsed symptoms in English but denied them in Spanish (

29 ). Patients spoke in the present tense more often in English than in Spanish, suggesting current rather than past symptoms (

29 ). In the study by Marcos and colleagues (

28,

29 ), psychiatrists viewed recordings of evaluations conducted without an interpreter; patients were Spanish speaking but conversant in English. Evaluations conducted in each language were evaluated by psychiatrists who spoke the same language (English or Spanish). Thus the effects of rater and patient language were confounded. Higher scores were given to patients assessed in English (by English-speaking psychiatrists) than those assessed in Spanish (by Spanish-speaking psychiatrists) on the subscales anxiety, tension, mannerisms and posturing, somatic concern, emotional withdrawal, depressive mood, and hostility. Scores on these subscales may have been influenced by characteristics of speech, such as fluency, rate, and productivity (

28,

29 ). In Price and Cuellar's study (

30 ), patients were rated in both languages by bilingual raters who may have attributed speech disturbances in English to challenges of communicating in a second language rather than to psychopathology. However, because detailed BPRS score profiles were not reported, it is not possible to compare the total scores between the two studies or to determine which subscales were elevated.

In Germany, Turkish and German psychotic patients were interviewed with the Schedules for the Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (SCAN) by a monolingual German-speaking psychiatric trainee without an interpreter and by a bilingual psychiatric trainee (

32 ). The trainees disagreed on the diagnosis for 4% of German patients and 19% of Turkish patients. The relative percentages of disagreement were similar for Turkish patients with "good" and "bad" German proficiency; however, the method of assessing proficiency was not described. The authors speculated that diagnostic uncertainty may be more closely linked to patients' level of acculturation than to their language proficiency. Alternately, psychometric properties of the Turkish and German versions of the SCAN may differ, accounting for some observed differences.

Taken together, these studies suggest that psychiatric assessments conducted in a nonnative language may be less reliable, although the effect on overall impressions of psychopathology may vary according to symptom type (

28,

30,

32 ).

Seven of the 14 empirical studies addressed the effects of interpreters on psychiatric assessment and diagnosis. In two studies, researchers audiotaped evaluations of patients in which ad hoc interpreters were used (

33,

34 ). Errors in interpretation resulted from interpreters' inadequate language proficiency; their lack of psychiatric knowledge, which led to normalization of patients' disordered thought process; interjection of their attitudes or editorializing comments; and their providing answers for patients without first interpreting the question for them (

33,

34 ). [Table A2 in the second online supplement to this article, available at

ps.psychiatryonline.org, categorizes types of errors with illustrative examples.] Interpreters with less English proficiency made more errors (

34 ). A hospital orderly with no interpreter training but some experience made more addition errors (that is, interjecting phrases), whereas a less experienced orderly made more distortions of clinicians' questions (

34 ). Interpretation errors were twice as likely to occur when patients spoke than when physicians spoke and were more likely with acutely psychotic patients than with nonpsychotic patients (

34 ). Similarly, when patients provided lengthy or convoluted replies, omissions were especially likely. Interpreters may have difficulty registering and remembering a patient's statement if they cannot discern its meaning (

34 ). Similarly, in South Africa, both ad hoc interpreters (for example, bilingual nurses) and professional interpreters failed to translate psychotic patients' actual statements (

31 ). Bilingual nurses were less likely than professional interpreters to report that they could not follow the patient; instead they asserted their opinion that the patient was psychotic. Clinicians, however, preferred working with these nurses over professional interpreters who withheld judgments (

31 ).

In England evaluations of patients with good or limited English proficiency were audiotaped and transcribed; the patients underwent two evaluations—one by an English-speaking psychiatrist with a professional interpreter and one by a bilingual psychiatrist (

35 ). The professional interpreter made errors, including omissions, condensations, conceptual substitutions, and miscommunications that were attributed to the interpreter's inadequate language skills. Nevertheless, both psychiatrists generated similar overall checklist ratings of patients' mental state. Methodological limitations may have obscured potential differences. Specifically, the interpreter knew that the study aimed to compare the two types of evaluations, and the same psychiatrist assessed patients and transcribed encounters.

Two studies reviewed medical records from initial health screenings of refugees seeking asylum in Switzerland (

36,

37 ). Use of professional interpreters was associated with increased disclosure of traumatic events and psychological symptoms, compared with use of ad hoc interpreters or no interpreter (

36 ). Patients reported few physical or psychological symptoms in encounters without an interpreter or when providers reported that communication was poor, and patients reported more symptoms during encounters with professional interpreters (

37 ). However, the presence of an ad hoc interpreter, typically a family member or friend, was associated with reports of many physical symptoms but few psychological symptoms (

37 ). Thus disclosure of psychological symptoms may be more sensitive to language barriers than disclosure of physical symptoms.

In Saudi Arabia a review of charts of primary care patients found that Arabic-speaking physicians and non-Arabic-speaking physicians using interpreters (professional or ad hoc) diagnosed mental disorders at similar rates (

38 ). Although this finding suggests that some physicians made psychiatric diagnoses after evaluating patients whose language they did not speak (patients' primary language was not reported), this study provided little insight into either the accuracy of physicians' assessments or physicians' ability to differentiate among psychiatric disorders, both critical prerequisites for high-quality care.

Results from these empirical studies indicate that interpreter-mediated encounters are prone to errors, although the clinical significance of errors varied among studies. Nevertheless, interpreters (especially professional ones) appear to facilitate more complete disclosure, which is a crucial component in ensuring accurate psychiatric assessments.

Patient-provider interaction

A heterogeneous group of studies, reviewed under the theme of patient-provider interaction, addressed how language proficiency or interpreter use affects the process of psychiatric care from the perspective of patients or providers.

Two studies that used video-recordings of Spanish-speaking patients found less verbal production by psychotic patients with limited English proficiency during English-language evaluations than during evaluations conducted in Spanish (

29,

30 ). During evaluations conducted in English, patients made significantly more short replies to questions that were identical in the Spanish interview, demonstrated slower speech and more pauses and disturbances (such as incomplete sentences, repetition, stuttering, and incoherent sounds) (

29 ), and scored lower on ratings of self-disclosure (

30 ).

Another study examined clinicians' impressions of their ability to create case formulations for Latino outpatients in one of two situations: in-person encounters with patients during which an ad hoc interpreter assisted or watching videotaped interviews with the help of an ad hoc interpreter (the interviews were conducted in Spanish by other clinicians) (

40 ). In both situations, clinicians reported a high degree of confidence in their assessments and believed that the interpretations provided to them by the interpreters were accurate and free from bias. Most clinicians reported that use of an interpreter led to assessments of diagnosis and functioning that were of equal or greater severity than assessments they would have made without an interpreter. However, patients' language proficiency was not assessed, and the assessments of English-speaking and Spanish-speaking clinicians were not compared, limiting the ability to determine the accuracy of clinicians' assessments. Similarly, there was no direct assessment of the interpretations to determine whether errors or bias may have been undetected by clinicians.

A study of nurse evaluations of asylum seekers in Switzerland found that only professional interpreters had a beneficial impact on communication (

36 ). Nurses rated communication as "poor" or "fair" in 84% of evaluations without an interpreter, 72% of those with ad hoc interpreters, and only 6% of those with professional interpreters.

Patients and psychiatrists may have differing views of evaluations conducted with use of interpreters (

41 ). Compared with Spanish-speaking patients seen without an interpreter, significantly more patients seen with an interpreter (type not specified) reported that they gained self-understanding and found the visit helpful. In contrast, the psychiatric residents who conducted the evaluations were unanimous in feeling that they provided less help to patients whom they saw with interpreters than to those whom they saw without interpreters. Most patients who were seen with an interpreter wanted a return visit; however, a minority of the residents believed that these patients wanted to return, and only one reported feeling comfortable seeing a patient with an interpreter for ongoing care. The authors postulated that residents projected their discomfort with treating patients who had limited English proficiency onto the patients, which prevented the residents from acknowledging patients' feelings of being helped and their desire for continued care. In contrast to the positive experiences of patients in this study, some patients in South Africa with limited English proficiency refused to utilize interpreters for various reasons: they were insulted that their English skills were perceived as inadequate, they wanted to avoid interference by third parties, or they had overt paranoia regarding the interpreter (

31 ).

Overall, psychiatric care of patients with limited English proficiency that is provided without interpreters may lead to incomplete patient disclosure and thus limit the effectiveness of evaluation and treatment. Results are mixed on how ad hoc interpreters may affect patient-provider interaction, with some studies suggesting negative effects and others indicating a benefit. Research addressing how professional interpreters influence patient-provider interaction is lacking; however, one study did report improved patient-provider communication. Patients and providers may hold divergent views of the benefits of interpreter-mediated visits.

Summary of findings

Patients provided longer replies with greater disclosure when interviewed in their first language compared with a nonnative language (

29,

30 ). When evaluating patients in English without interpreters, clinicians may alter their interview style to discourage lengthy replies, thus biasing assessments (

31 ). Clinicians may understand short replies to signify a hostile or guarded mental state, intellectual impairment, impoverished thoughts, withdrawal, or tension. In one study Spanish-speaking psychotic patients who were conversant in English were rated similarly on positive symptoms when evaluations were conducted in English or in Spanish, but in the English evaluations they received higher ratings (indicating more severe symptoms) on domains most likely to be influenced by communicating in a nonprimary language (

28 ). However, another study found that clinicians documented less overall psychopathology among bilingual patients during English-language evaluations than during Spanish-language evaluations (

30 ). Therefore, English-language evaluation of patients with limited English proficiency may obscure mental status findings among patients with schizophrenia (

28,

30 ), and the effects of language proficiency may vary according to symptom type (

28 ). For example, it is not known whether language proficiency affects the communication of symptoms of depression or anxiety in ways that differ from the communication of psychotic symptoms. Finally, studies using structured interviews (

28,

29,

30,

32,

35,

36,

37 ) do not represent clinical practice, which suggests the need for research in naturalistic settings.

Use of ad hoc interpreters may impede disclosure of sensitive material (

33,

37 ) and contribute to distortions and errors (

33,

34 ). Errors have been shown to occur more often for acutely ill patients (

34 ) and may lead to over- or underestimation of psychopathology (

33 ). Nevertheless, some clinicians are confident in assessments conducted with such interpreters (

40 ). Compromised disclosure with ad hoc interpreters may yield fewer referrals for follow-up care (

36,

37 ), which may have an impact on treatment and health outcomes. Professional interpreters, however, may facilitate improved disclosure (

36,

37 ). Although errors also occur in encounters mediated by professional interpreters, their clinical impact may be less substantial (

35 ). Standards for mental health interpreting do not exist, and both ad hoc and professional interpreters may lack sufficient language skills to facilitate the communication needed for high-quality psychiatric care (

34,

35 ). More systematic study of the clinical consequences is warranted.