As health care costs rise, there is increasing interest in the characteristics of service users. Trauma history has been identified as an important predictor of greater service use (

1,

2 ). Child abuse and neglect (also referred to as childhood maltreatment) is a major source of trauma; several studies have described high rates of general medical and mental health care among adults who report childhood maltreatment. For example, women who reported histories of child abuse had more annual primary care visits (

3,

4 ) and greater median annual costs for general medical care (

5,

6 ) than persons without such histories. However, because childhood maltreatment is also a predictor of psychiatric problems in adulthood, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and substance abuse (

7,

8,

9,

10 ), it is possible that the relationship between childhood abuse and service use depends on whether the person has a psychiatric disorder.

Studies have found that the impact of childhood sexual abuse on service use (including emergency room and inpatient psychiatric and general medical services) is moderated by the presence of depressive symptoms (

3,

11 ). Simpson (

12 ) observed that women with a history of childhood abuse and a history of substance abuse problems were less likely than other women to use addiction services but more likely to use mental health services. The relationship between childhood maltreatment and the use of social services, such as child welfare, housing, public assistance, and food banks, has seldom been studied.

As noted, the literature suggests that childhood abuse and neglect may be associated with greater use of services. At the same time, the existing literature has several limitations. Most studies of adults have focused on women and do not examine outcomes for men. These studies also tend to focus on sexual abuse, with few studies of childhood physical abuse or neglect. In addition, there is an almost exclusive reliance on retrospective self-reports of childhood abuse, which has resulted in some ambiguity because of forgotten or undisclosed abuse and experiences that would not meet an objective standard of abuse or neglect.

This article describes the first prospective assessment of service use in a large sample of male and female children with documented cases of childhood abuse and neglect and a matched comparison group who were followed up and assessed in adulthood (approximate age 41). Addressing questions explored by previous studies that had different methodologies, as well as new issues, this study examined the following questions: Are adults with documented histories of childhood abuse and neglect more likely to use mental health, substance abuse, general medical, or social services than persons in a matched control group? Is service use associated with the type of childhood abuse or neglect experienced (physical or sexual abuse, neglect, or multiple types of abuse)? Does psychiatric status (PTSD, drug abuse, or major depressive disorder) mediate the relationship between childhood maltreatment and service use in adulthood? Does psychiatric status moderate the relationship between childhood abuse and neglect and service use in adulthood?

We hypothesized that individuals with documented histories of childhood maltreatment would be more likely to report using mental health, general medical, substance abuse, and social services in middle adulthood than persons in a matched control group and that this relationship would be manifest for all types of childhood abuse and neglect. On the basis of the logic that childhood abuse leads to adult psychiatric disorders and that psychiatric disorders in turn lead to service use, we hypothesized that individuals with documented histories of all types of childhood abuse and neglect would be more likely than those in the matched control group to report using services in middle adulthood and that this relationship would be largely mediated by a history of psychiatric disorder in young adulthood. Furthermore, on the basis of the view that psychiatric disorders increase distress associated with general medical problems—and following previous studies (

3,

11 )—we also hypothesized that the relationship between childhood abuse and neglect and service use would be moderated by a history of psychiatric disorder in young adulthood, such that persons with both psychiatric and maltreatment histories would report greater service use. Even though previous studies have reported this relationship only for women with sexual abuse histories, we hypothesized that this moderation effect would also be seen for men and for persons with histories of other types of maltreatment.

Methods

Participants

The data are from a large prospective cohort-design study in which abused or neglected children were matched with nonvictimized children and followed prospectively into adulthood (

13 ). Because of the matching procedure, the participants are assumed to differ only in the risk factor: having experienced childhood abuse or neglect.

Cases of child abuse and neglect were drawn from the records of county juvenile and adult criminal courts in a metropolitan area in the Midwest during the years 1967 through 1971. The rationale for identifying the abused and neglected group from these records was that their cases were serious enough to come to the attention of the authorities. Only court-substantiated cases of child maltreatment were included. Abuse and neglect cases were restricted to those in which the children were less than 11 years old at the time of the incident. Physical abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect cases were included, and court cases that represented only adoption, involuntary neglect, child placement, or failure to pay child support were excluded. Physical abuse cases included injuries such as bruises, welts, burns, wounds, or bone and skull fractures. Sexual abuse cases ranged from those with relatively nonspecific charges of "assault and battery with intent to gratify sexual desires" to more specific charges of rape, sodomy, and incest. Neglect cases reflected a judgment that the parents' deficiencies in child care were beyond those found acceptable by community and professional standards at the time. These cases represented extreme failure to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, and medical attention to children. [Further description of the sample and matching procedures are provided in an online supplement to this article at

ps.psychiatryonline.org .].

A comparison group was selected that was matched with the maltreated sample on the basis of age, sex, race-ethnicity, and approximate family social class during the period under study. Use of school and hospital records provided matches for 74% of the abused and neglected children (N=667).

The first phase of this research involved identification of the groups and collection of official criminal history information (N=1,575) (

14 ). Participants were interviewed between 1989 and 1995 (N=1,196) and in 2000–2002 (N=896). Data for the study reported here were collected in the context of a medical status examination and interview during 2003–2004 (N=807: 458 in the abuse and neglect group and 349 in the control group).

Over the course of the study, there was attrition associated with death, refusal to participate, and inability to locate individuals; however, the characteristics of the sample at the four time points have remained roughly the same. Over the four phases of the study, no significant differences were found across the samples in race-ethnicity, sex, or age; white non-Hispanics constituted 59%–62% of both groups and females constituted 49%–53% of the groups. The abuse and neglect group represented 56%–58% of the total sample at each period, and the proportion of abuse subtypes did not differ across the four study phases, with 9%–10% of the total sample in the physical abuse subgroup, 8%–10% in the sexual abuse subgroup, and 44%–46% in the neglect subgroup (these percentages sum to more than the percentage with childhood maltreatment in the sample because some individuals experienced more than one type of maltreatment).

The mean age of the total sample at follow-up was 41.20±3.54 years. Approximately half the sample was female (N=426, 53%) and non-Hispanic white (N=478, 59%). The nonwhite group included African Americans (N=299, 35%), Hispanics (N=32, 4%), and others (N=21, 3%). Only 28% (N=211) had at least some college (data on education were missing for 52 participants). The median occupational status level (N=130, 22%) for the sample was service, and only 71 (12%) were in the professions (

15 ). (Data on occupation were missing for 201 participants, 148 of whom were not employed or not looking for work for various reasons). Thus the overall sample had a large proportion of persons of lower socioeconomic status.

Interviewers were blind to the purpose of the study and to the participants' group membership. Similarly, participants were blind to the purpose of the study and were told that they had been selected to participate as part of a large group of individuals from that geographic area. Institutional review boards approved the study, and participants provided informed consent.

Measures

Service use. For the 2003–2004 interviews, we developed a structured interview about contact with health and social service professionals in the past 12 months (past-year use). Providers were grouped into four sectors: general medical, mental health (psychiatrist, psychologist, or other mental health), substance abuse, and social services (the most common reasons for seeking social services were to obtain assistance with food, shelter, and Medicaid).

PTSD, major depressive disorder, and drug abuse. The Diagnostic Interview Schedule-III-R (DIS-III-R) (

16 ) was administered to participants during 1989–1995, when the participants were approximately age 29 (

9,

17,

18 ). The DIS-III-R is a structured interview schedule designed for use by lay interviewers; it has adequate reliability (

19 ). Field interviewer supervisors recontacted a random 10% of the respondents for quality control. For the analyses reported here, we used information on lifetime diagnoses of PTSD, major depressive disorder, and drug abuse from the 1989–1995 interviews.

Control variables. Demographic variables (including race-ethnicity, gender, and age) were used as controls.

Statistical analysis

Chi square tests were used to assess bivariate relationships between child abuse and neglect and the dichotomous indicators of service use. Logistic regression was used to determine the relationship between childhood maltreatment and past-year service use. Regression analyses were conducted for child abuse and neglect overall (compared with the control group) and each type of abuse or neglect (compared with the control group). Potential mediators were introduced into logistic regression equations along with group status (abuse or neglect group compared with the control group). Interactions of abuse or neglect by gender and abuse or neglect by psychiatric status were tested by adding a product term to the main effects model. The number of participants varied slightly in each analysis because of missing data. SPSS, version 15, was used for all analyses.

Results

Child abuse and neglect and service use

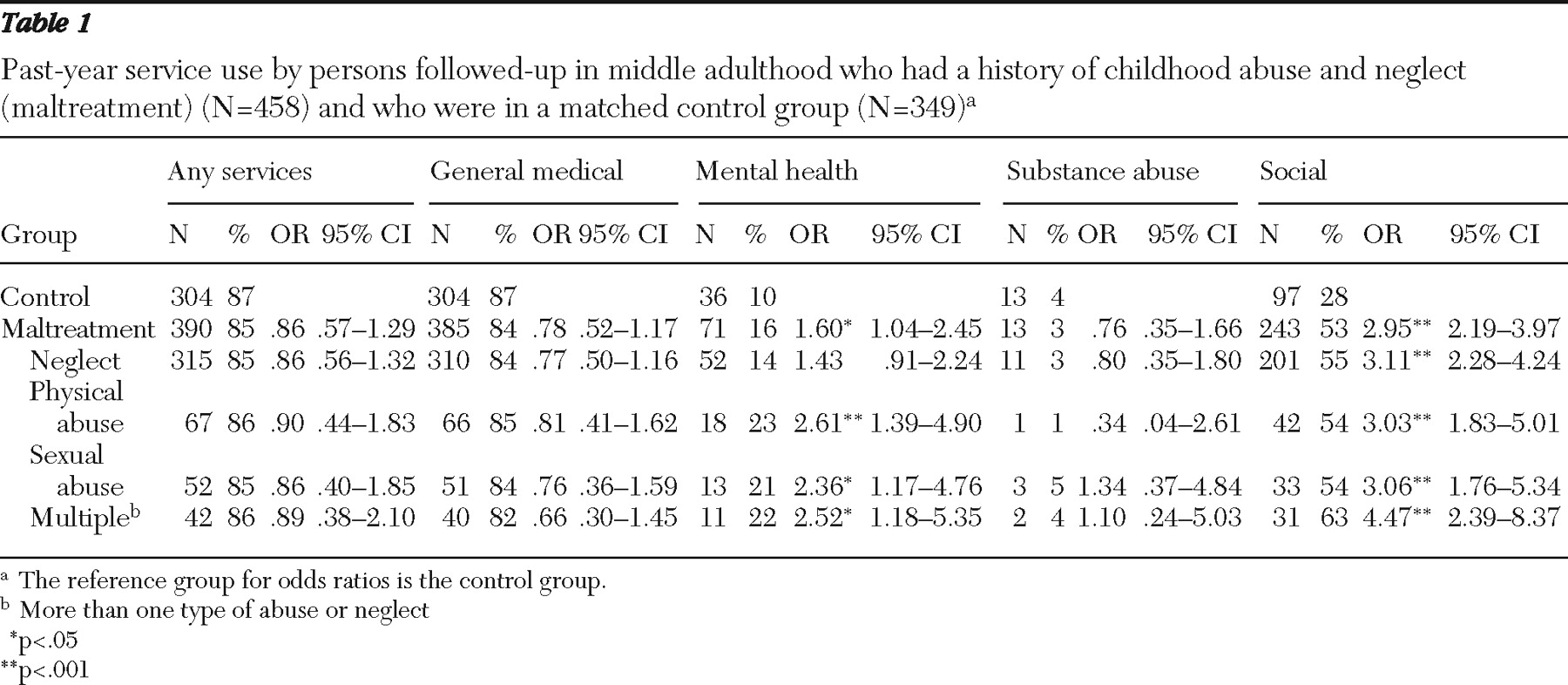

Table 1 shows past-year service use in middle adulthood among abused and neglected individuals and persons in the matched control group. As hypothesized, abused and neglected individuals were more likely to use mental health and social services in adulthood than their counterparts in the control group. Contrary to expectation, however, childhood maltreatment was not associated with greater past-year use of general medical services, substance abuse services, or any services. No significant interactions between group (abuse and neglect group) and sex were found for service use.

Type of abuse or neglect and service use

As shown in

Table 1, individuals with documented histories of childhood physical and sexual abuse and those who had experienced more than one type of childhood abuse or neglect (multiple types) were more likely than their counterparts in the control group to report using mental health and social services as adults. Neglected children were significantly more likely than those in the control group to report having used social services during the past year; they were also more likely to report having used mental health services during the past year, but the difference was not significant.

Mediation analyses

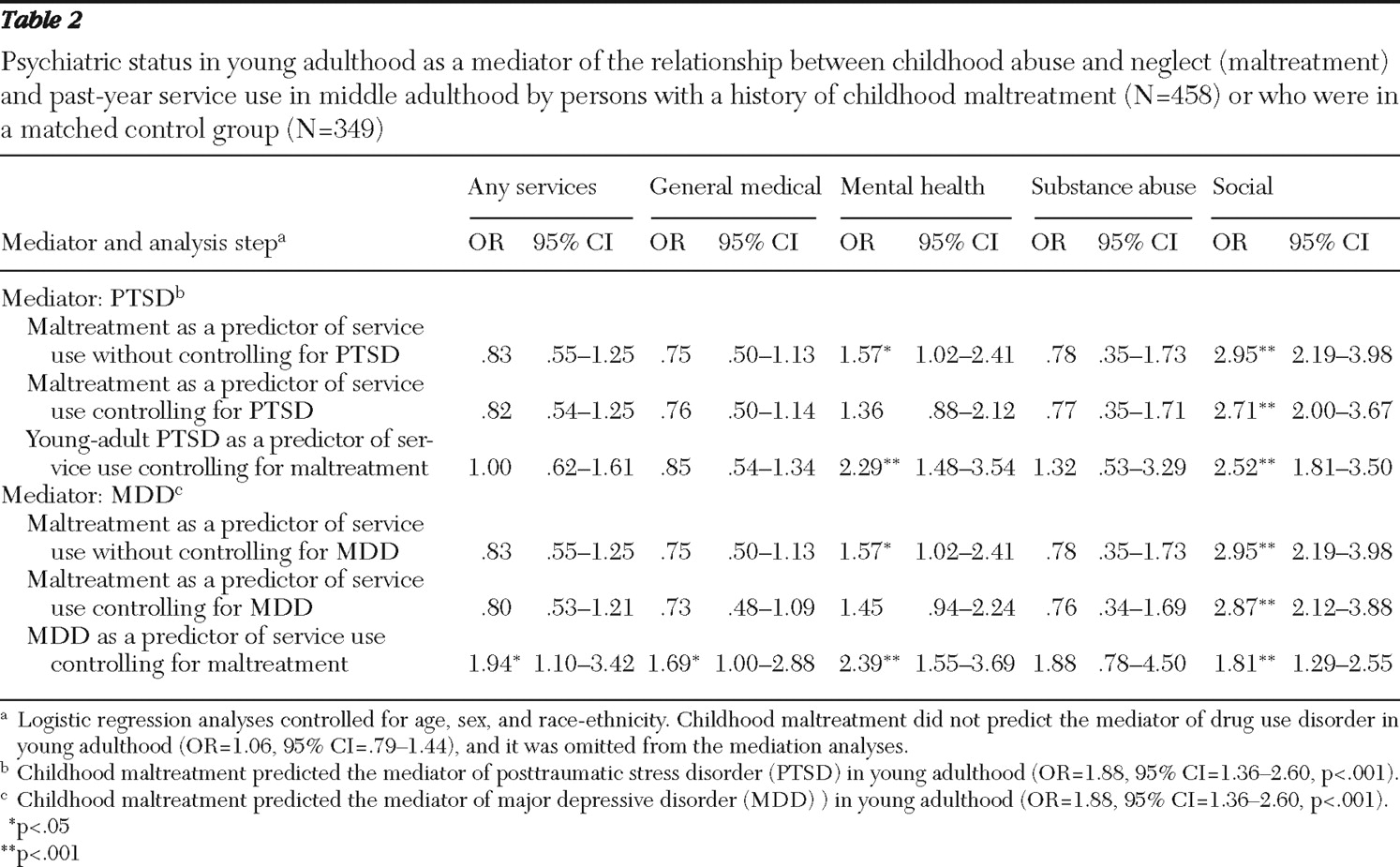

Mediation analyses are shown in

Table 2 . All analyses control for age, sex, and race-ethnicity. Following recommended steps for testing mediation (

20 ), we first determined whether abuse or neglect in childhood predicted service use in adulthood. We found that childhood maltreatment predicted mental health and social services use in middle adulthood. The second step was to determine whether childhood abuse or neglect predicted the hypothesized mediators. The results indicated that childhood maltreatment predicted PTSD and major depression in young adulthood but not drug abuse. Therefore, drug abuse was dropped from further mediation analyses. The third step was to determine whether the hypothesized mediators predicted service use in middle adulthood, controlling for childhood abuse or neglect as well as the demographic variables. Evidence of mediation would be indicated by a reduction in the magnitude of the relationship between childhood abuse and neglect and service use when the mediators were included in the equation.

Our results indicate that having a lifetime diagnosis of PTSD and major depression partially mediated the relationship between childhood abuse and neglect and mental health service use in middle adulthood. Notably, the effect of childhood maltreatment on mental health service use did not remain significant when young-adult PTSD and major depression were each included as mediators. Although there was some evidence (albeit less compelling) for mediation of social service use, the relationship between childhood maltreatment and social service use remained significant despite the introduction of the potential mediators (PTSD and major depression), suggesting that some other factors contributed to the greater likelihood of social service use among adults with documented histories of childhood maltreatment.

Moderation analyses

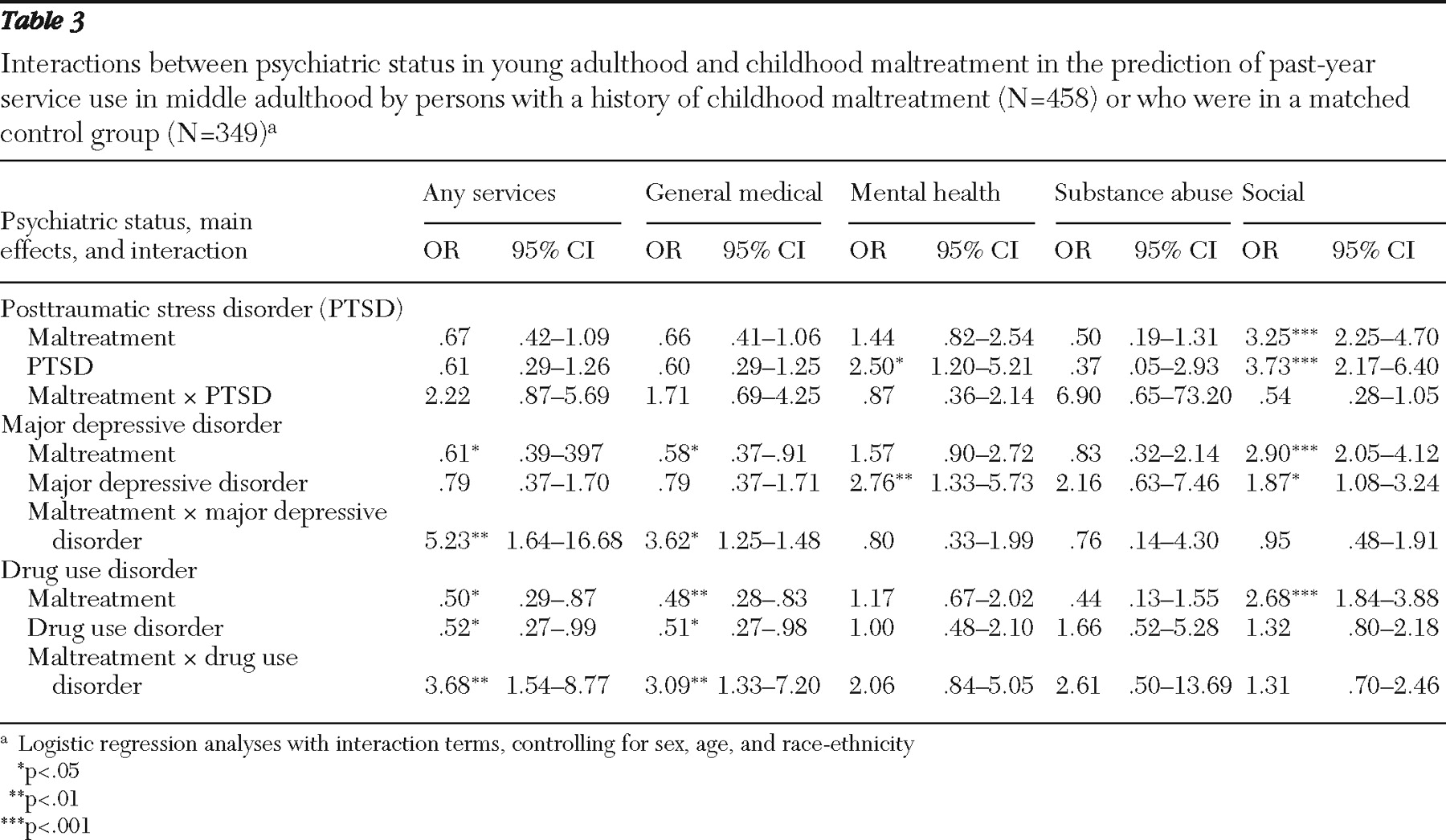

We next tested the hypothesis that having a diagnosis of PTSD, major depression, or drug abuse in young adulthood interacts with child abuse and neglect to predict service use in middle adulthood (

Table 3 ). These analyses indicated significant interactions between childhood maltreatment and both major depression and drug abuse in young adulthood in predicting use in middle adulthood of any service and of general medical services. There were no significant interactions between childhood maltreatment and PTSD on service use. These results indicate that abused and neglected individuals with a diagnosis of major depression or drug abuse in young adulthood were more likely than those without these disorders to report using any services and general medical services in middle adulthood, whereas this was not the case for their counterparts in the control group.It should be noted that the relationship with use of any services was primarily driven by the relationship with general medical service use.

Discussion

Findings from this prospective follow-up indicate that individuals with documented histories of childhood abuse and neglect were more likely to use mental health and social services in middle adulthood than those in a matched control group without such histories. We found that having a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse and having experienced more than one type of childhood abuse or neglect predicted past-year use of mental health services in middle adulthood and that all types of childhood abuse and neglect predicted use of social services.

Our results indicate that having a diagnosis of either PTSD or major depression in young adulthood partially mediated the relationship between childhood maltreatment and the use of mental health services in middle adulthood. This suggests that the relationship between childhood maltreatment and mental health service use was explained in part by the increased risk of having a psychiatric disorder that is associated with maltreatment. There was weaker evidence that these psychiatric disorders mediated the relationship between childhood abuse and neglect and use of social services because childhood abuse and neglect had an independent and robust relationship with social service use even when mediators were included in the equation. We considered the possibility that use of social services was driven by either involvement with child protective agencies (in the event that adults were repeating child abuse and neglect that they had experienced as children) or the impact of socioeconomic status. However, post hoc analyses indicated that these types of services accounted for a minority of social services used. Post hoc analyses indicated instead that a wide variety of social services was used, suggesting that further research is warranted to understand the reasons why persons with histories of abuse and neglect are more likely to use social services.

Consistent with previous research (

3,

11 ), our results indicate that having a diagnosis of major depression in young adulthood moderated the impact of childhood abuse and neglect on general medical service use in middle adulthood. Newman and colleagues (

11 ) speculated that the combination of a history of childhood sexual abuse and depression would lead to a greater number of "somatic" complaints, which would in turn lead to more use of general medical services. Although our study was not able to explore this, it is plausible that the combination of a history of childhood maltreatment and major depression leads to an increase in somatization, which leads individuals to use more general medical services.

A new finding that emerged from our analyses is that having a drug abuse diagnosis in young adulthood moderated the impact of childhood maltreatment on use of general medical services. Domino and colleagues (

21 ) noted that women with combined substance use, psychiatric problems, and trauma histories have very high rates of service utilization. Our finding that depression and drug use moderated the effect of abuse and neglect on use of general medical services suggests that a subset of maltreated individuals with psychiatric or drug use problems may account for the higher rates of service utilization noted by Domino and colleagues.

Our finding that increased risk of major depression and PTSD associated with childhood abuse and neglect was related to increased use of mental health services suggests that persons are seeking care in the appropriate sector. However, having a psychiatric disorder in young adulthood predicted use of mental health services in middle adulthood. These findings suggest that for a number of these participants, their mental health status may have become persistent or their problems were not responsive to treatment. It has been documented that PTSD and other trauma-related conditions are rarely assessed and treated in the public mental health system or are treated with untested interventions (

22 ); therefore, our findings suggest that greater efforts to screen for trauma history are warranted. It should be noted that because our results showed only partial mediation, it is likely that a number of participants had mental disorders in middle adulthood that had not yet appeared in young adulthood or had prior psychiatric problems that had been resolved by middle adulthood.

In contrast with previous studies (

3,

4,

23 ), our study did not find a relationship between abuse and neglect in childhood and general medical service use. Methodological differences between our study and those of previous studies (prospective longitudinal versus cross-sectional, documented cases versus retrospective self-reports) may explain this discrepancy. Prior research has suggested that over a third of persons with documented histories of childhood physical abuse and sexual abuse do not self-report a history of abuse (

24,

25 ), and thus many of the individuals in our maltreated sample would not have been included in other studies. Furthermore, several previous studies used medical records data to document service utilization and were thus able to record service use more reliably, as well as capture information on frequency of service use (

3,

4,

23 ). The study reported here relied on self-reports of past-year service use and represented service use dichotomously and thus may have missed differences in the amount of health and mental health services used by the two groups. Future research should seek to further clarify this distinction. In addition, it is possible that self-reports of service use may underestimate actual service use. Research on the accuracy of self-reports of past-year health service use has been mixed (

26,

27 ).

Despite the study's strengths, we note further limitations that may have an impact on the generalizability of its findings. There was attrition across the four phases of this study. Although analyses did not show significant differences in the demographic characteristics of participants across the phases, it is possible that those who remained in the study may differ on other characteristics. Furthermore, our findings are based on cases of childhood abuse and neglect drawn from official court records and most likely represent the most extreme cases processed in the system. If there was unreported abuse or neglect in the control group, then the study may have underestimated the association between childhood maltreatment and service use. Although our matched control group was comparable to the abuse and neglect group in basic demographic characteristics, it remains possible that the groups differed in other, unmeasured ways. Finally, the sample included a large proportion of persons of lower socioeconomic status, and findings may not generalize to cases of abuse and neglect among children with higher socioeconomic status.

Conclusions

The results showed that individuals with documented histories of childhood abuse and neglect were more likely than their counterparts in a matched control group to use mental health and social services in adulthood. Although psychiatric status in young adulthood partially explained the relationship between childhood abuse and neglect and use of mental health services, additional factors may be operating. We also found that major depression and drug abuse in young adulthood magnified the relationship between maltreatment history and use of health and mental health services in middle adulthood.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This research was supported in part by grant HD40774 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, grants MH49467 and MH58386 from the National Institute of Mental Health, grants 86-IJ-CX-0033 and 89-IJ-CX-0007 from the National Institute of Justice, grants DA17842 and DA10060 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, grants AA09238 and AA11108 from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Points of view are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of the United States Department of Justice.

The authors report no competing interests.