Overall rates of mental disorder

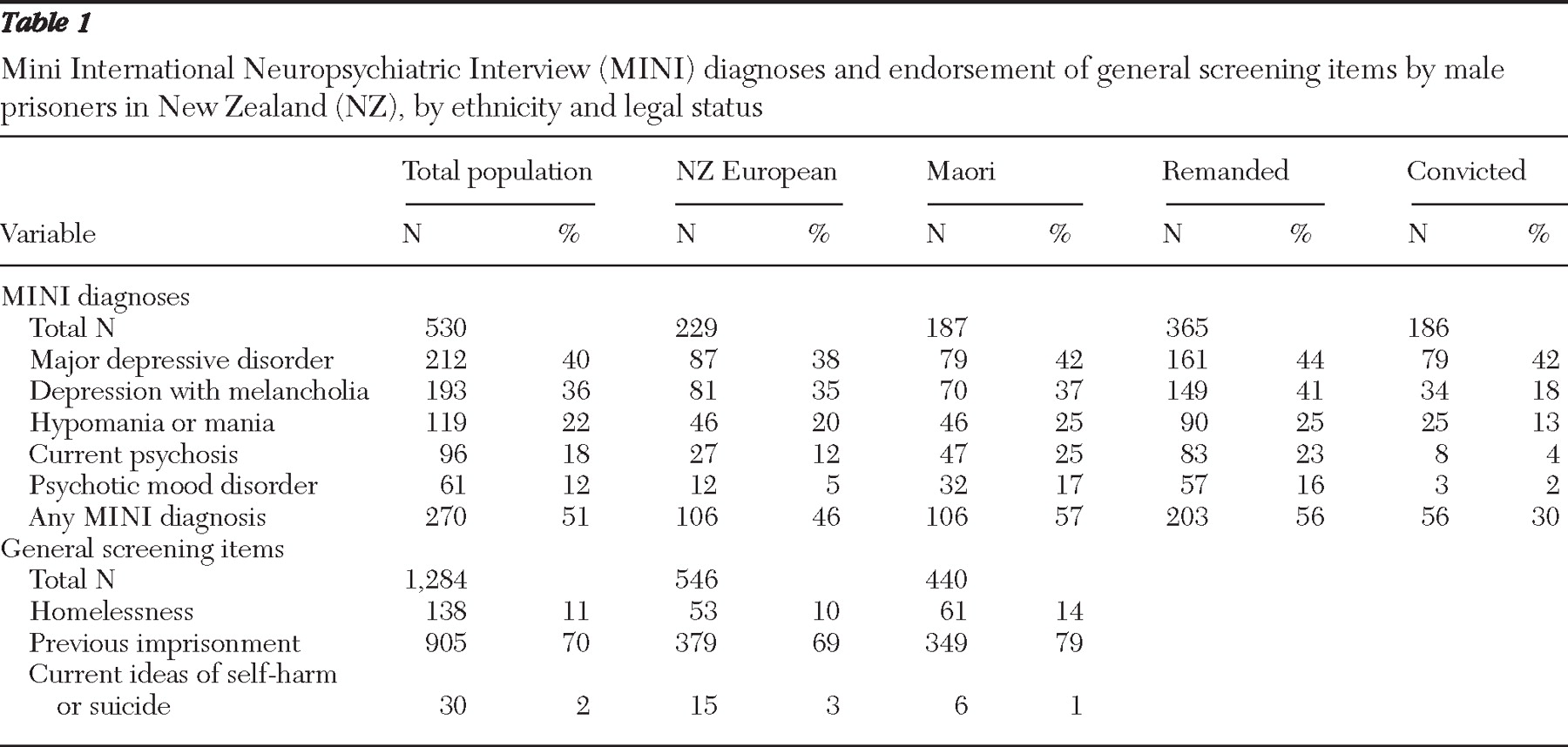

Using the MINI as the validating standard, we identified very high rates of serious mental illness in the New Zealand prison population, in line with previous international research (

2 ) and New Zealand research (

1 ).

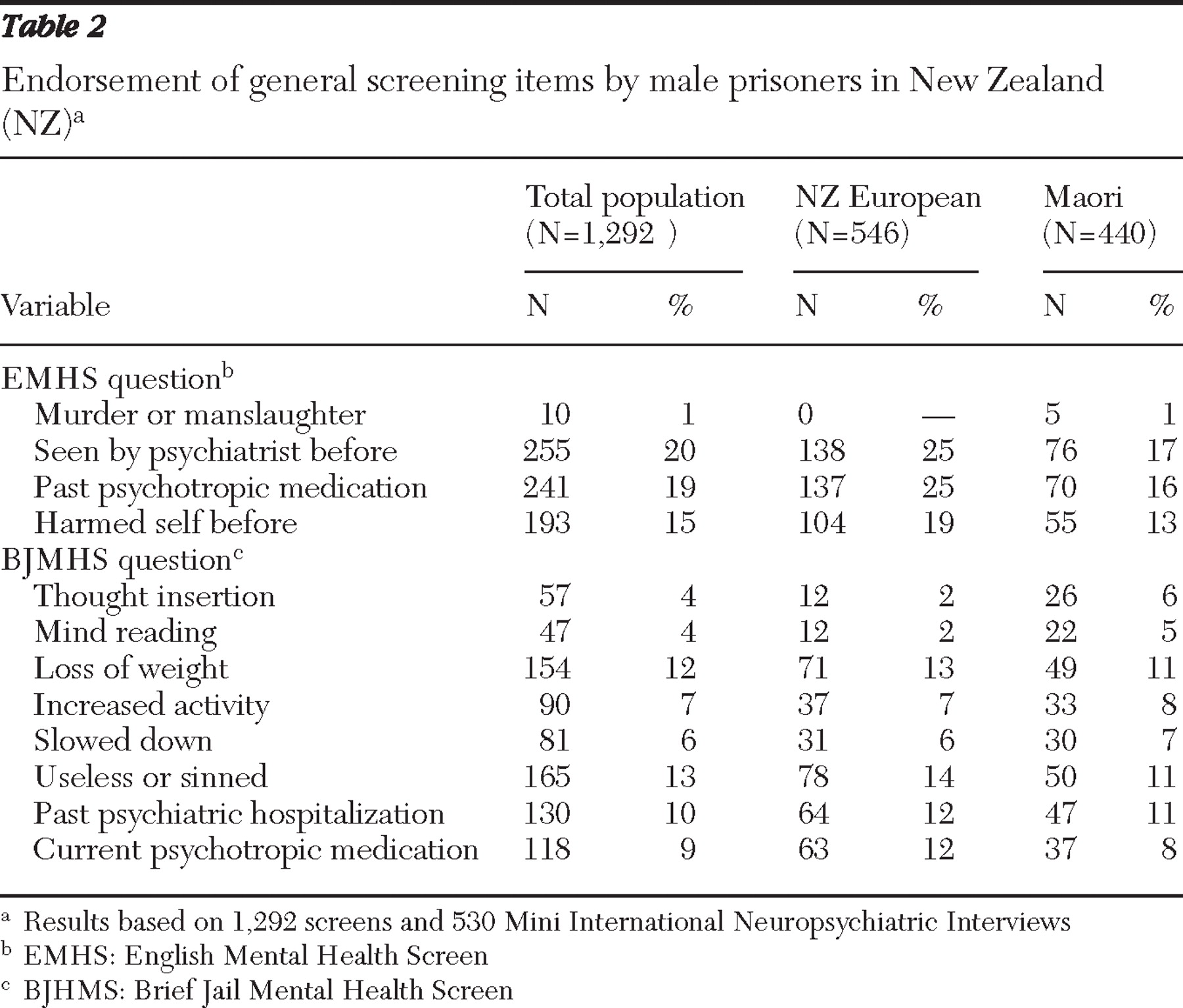

However, the rates of mental disorder in New Zealand prisons were significantly higher than the corresponding rates identified in the validation studies for the EMHS and BJMHS, which raises questions about the reliability and validity of the MINI as a standard diagnostic instrument in this context. There are several reasons that support the use of the MINI as a validation instrument. First, interrater reliability testing in Christchurch did not identify any systematic rater bias. Second, the prevalence rate of mental disorders (N=90, 20%) identified using the SADS-L in the United Kingdom was about half the level expected by the authors (

6 ), reducing the apparent discrepancy between their study and ours. Third, several clinical indicators, including high rates of previous hospitalization, consultation with a psychiatrist, or use of psychiatric medication, supported the presence of high psychiatric morbidity in our sample. Fourth, the MINI has been validated against other, more lengthy, gold standards, including the SCID (

8 ) and the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (

8,

9,

10 ). Finally, the MINI has an interview structure similar to the other gold standards, and there is no reason to suspect that the longer standard interviews would produce significantly different results for the New Zealand population.

It has also been argued that any epidemiological research that relies on structured diagnostic instruments runs the risk of finding arbitrarily high levels of mental illness because of the tendency to categorize general, common symptoms as a mental disorder. In the study presented here, very high rates of endorsement of depressive symptoms emerged, which may reflect an individual's transient response to adjusting to the stressful prison environment, with symptoms diminishing as adjustment occurs, rather than reflecting the true presence of a depressive disorder. It is possible that a clinical assessment would have greater ability to differentiate between an adjustment response with depressive symptoms and a true depressive disorder.

If the MINI is overinclusive in the manner described, our data are likely to underestimate the performance of the screening tools. Artificially high rates of mental disorders would lead to lower sensitivity ratings, because the screens would need to detect potential mental illness among those for whom a diagnosis was dubious.

Performance of the screening tools

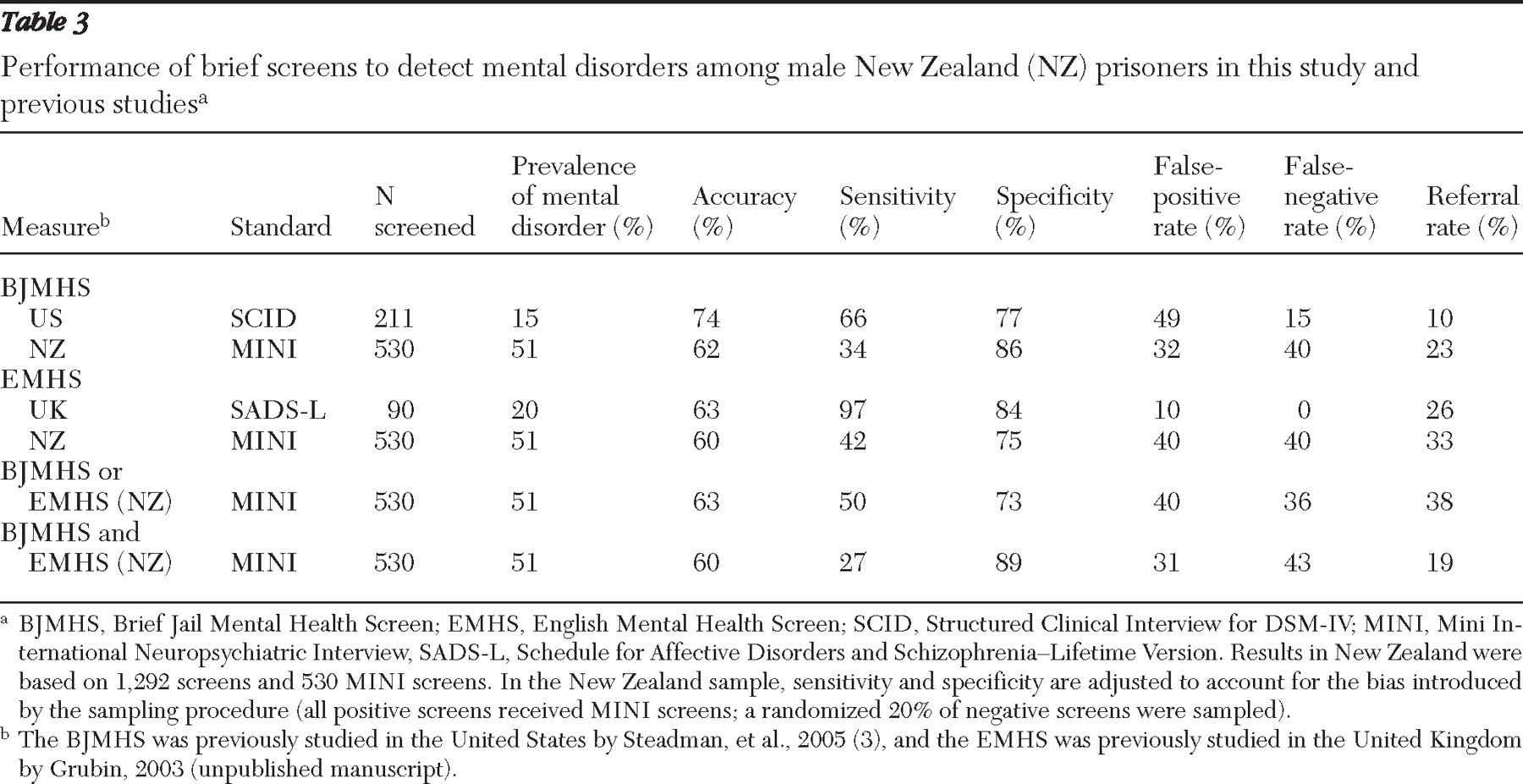

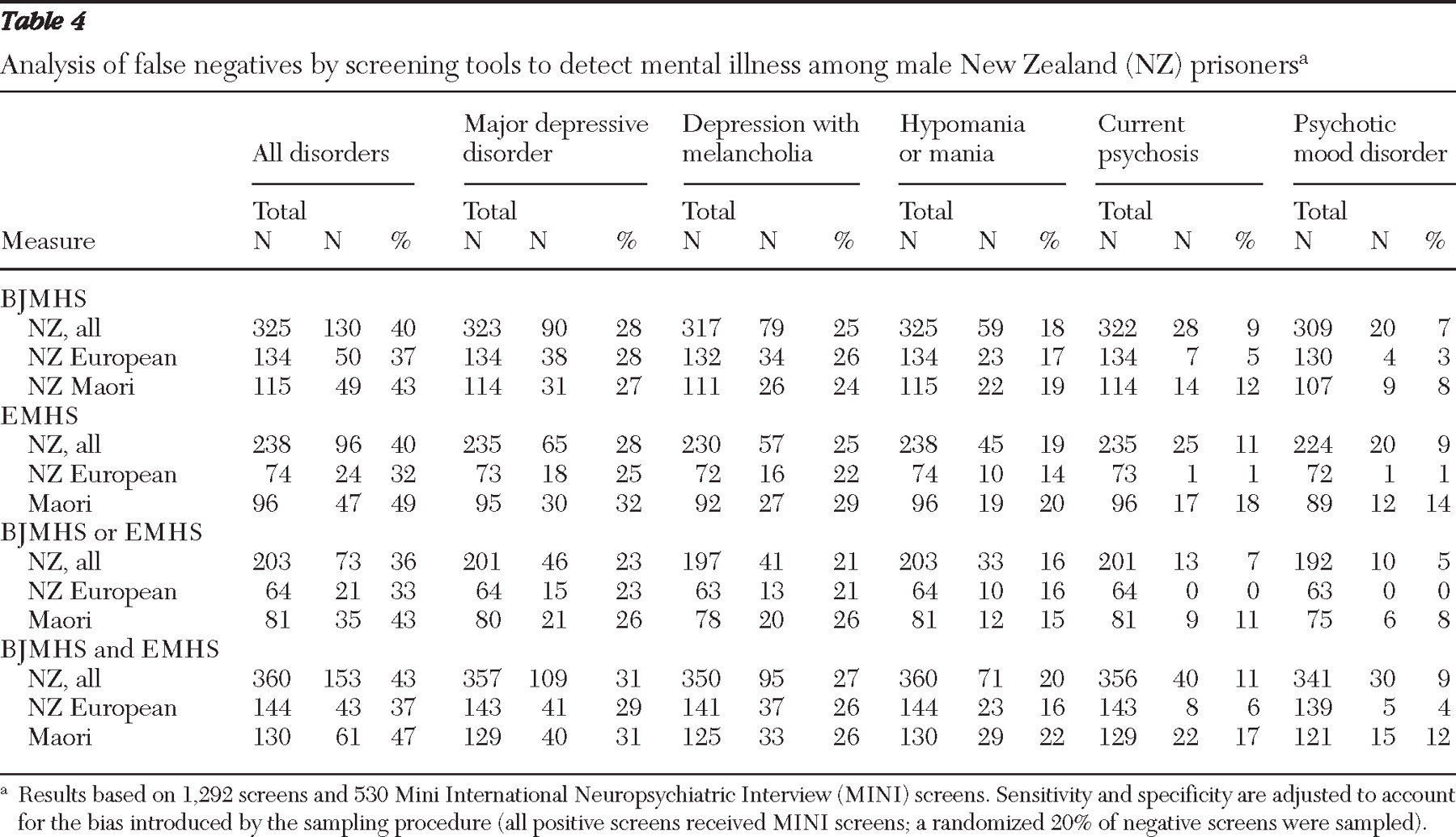

The basic performance data suggest that neither the BJMHS nor the EMHS was particularly effective as a diagnostic screening tool for mental disorders in New Zealand prisons. However, secondary analysis of false-negative cases suggested that the screens were effective in identifying individuals with psychosis, although the screens were not as specific in detecting mood disturbance. It is arguable that depressive symptoms are such a common finding in the prison setting that it is not desirable for the screening tool to screen individuals as being positive on the basis of these symptoms in the absence of, for example, psychosis or suicidality.

The implications of a false-negative and a false-positive finding should be interpreted with the prison context in mind. If a prisoner with low-grade but persistent depressive symptoms screens negative, the implication is that the prisoner would continue to experience these symptoms without further mental health intervention, although the prisoner can still be identified after admission—for example, by officers on the prison wing who can observe the prisoner's longitudinal presentation. A false positive means that the prisoner with either current symptoms or a relevant psychiatric history will undergo further brief questioning by a mental health professional. Although service-level resource implications must be considered, the outcome for the individual is not harmful and could be beneficial.

Both the BJMHS and the EMHS had comparatively low levels of sensitivity in the New Zealand study. The pilot study of the EMHS in the United Kingdom appears to be the outlier in terms of an unusually good performance by a screening tool—that is, a zero rate of false negatives in the male prison population and extremely high sensitivity rates for depression, a disorder with a high prevalence, arising from a small number of general, historically based, and widely endorsed screening questions. Although we must not minimize the importance of detecting mood disturbance in the prison setting, it is somewhat reassuring that the lower levels of sensitivity of the screens in the New Zealand setting were predominantly due to the detection by the MINI of very high rates of mood disturbance; few cases involving psychosis went undetected by either screen.

The pattern and rate of mental disorders in the false-negative cases were remarkably similar for both the BJMHS and EMHS. Also, no single historical question in either screen appeared to be especially powerful in identifying prisoners with mental illness, and all questions appeared to contribute to the overall performance of the EMHS in detecting cases of psychosis.

Because of the prevalence of depressive symptoms in the prison setting and the relatively benign meaning of a false-positive screen at the individual level, it is arguable that the clinical priority for the study presented here should be the minimization of false-negative cases of psychosis. The specific diagnoses may be less relevant in this context than the detection of an at-risk population, specifically, those who are currently psychotic and those who are actively suicidal (which would be addressed by a supplementary screen). These cases require at least semi-urgent psychiatric assessment, and sometimes acute care is required.

In this sense, both the EMHS and the BJMHS perform adequately: although they have low sensitivity in terms of diagnoses, both the EMHS and the BJMHS were good at detecting psychosis. Although it would be simpler to use either the EMHS or the BJMHS, neither performed as well on its own as they did in combination, and the time that it takes to complete both screens is in line with current, nonvalidated approaches to screening in New Zealand. Overall, the most effective screening approach from a clinical perspective, particularly in terms of minimization of false-negative rates, was achieved by a screen where referral for mental health nursing assessment was triggered by a positive screen on either tool.

A two-tiered strategy for screening

Adopting a combination of both screens leads to the challenge of how to manage the high false-positive rate in terms of the demand placed on forensic mental health services. However, it should be noted that the developers of the BJMHS had a higher false-positive rate than that found in the study presented here, yet they felt able to endorse the screen for the male detainees in jail (

3 ). It is unlikely that a brief screening instrument will be able to be developed that can be administered easily by prison nursing staff and that does not produce significant levels of false-positive cases, making it unrealistic to pursue an ideal screening tool with a much lower referral rate.

The data presented here suggest that an effective strategy might be to introduce a second stage to the screening process, entailing a brief triage interview with a mental health professional for those who screened positive, in order to refer prisoners with symptoms of psychosis, mania, severe depression, and suicidality for specialist psychiatric assessment, as opposed to those with uncomplicated depressive symptoms, who could be reviewed by primary health care services. This approach would address the national cultural context by providing an opportunity for a focus on potential cultural considerations—for example, to identify cultural beliefs that may mimic psychosis. This two-stage screening strategy would resemble the three-stage model proposed in the American Psychiatric Association's guidelines for psychiatric services for jails and prisons (

11 ).