Assertive community treatment (ACT) is a widely investigated treatment model for persons with severe mental illness and is recognized as an evidence-based practice (

1 ). Typical outcomes include reduced dropout rates, reduced hospitalizations, increased housing stability, and higher client and family satisfaction (

2,

3 ). However, there is little evidence that ACT improves symptomatology, quality of life, and social functioning or has an impact on recovery-oriented domains, such as employment, education, and relationships (

4 ).

Although ACT is effective, it does not work for everyone. One way to understand this variability is to explore client successes and failures. Such an exploration provides information about mechanisms that underlie an intervention and ways to perfect or add to existing procedures (

5 ), and it clarifies what is being done well and what is not being done well and with whom. Currently however, there is no consensus definition of what constitutes treatment success or failure in ACT. Although research typically has operationalized success as decreased hospitalizations, this narrow outcome does not capture important recovery-related domains, such as hope and meaningful activities (

6,

7 ). Thus one important step is to determine how success and failure are defined in ACT. Second, because staff and consumer perspectives often differ (

8,

9 ), we also chose to compare staff and consumer definitions of success and failure.

Methods

Sites were four ACT teams in Indiana participating in a larger study of recovery in ACT. Six staff members representing the major disciplines on each team were targeted for recruitment: team leaders (N=4), psychiatrists (N=2), nurses (N=5), case managers (N=5), substance abuse specialists (N=4), and employment specialists (N=3). One team had no employment specialist, one psychiatrist was unavailable, and another psychiatrist refused to participate. Additionally, a therapist (N=1) and peer support specialist (N=1) participated; these are optional positions in Indiana. In total, six staff from three teams and seven staff from the fourth team participated (N=25). Twenty-three (92%) were Caucasian, one (4%) was African American, and one (4%) was Hispanic. Nineteen (76%) were female, and most were middle aged (mean±SD age=43.6±11.4).

All staff members were asked to identify the most and least successful consumers on their teams. Consumers were rank-ordered based on the number of staff nominations. On each team, consumers identified as the most (N=3) and the least successful (N=3) were contacted for interviews. Six consumers nominated as least successful could not be included because of incarceration (N=3), because they were not currently receiving services (N=2), and because of refusal to participate (N=1). In each case, the next-ranked consumer was notified and participated. One consumer nominated as most successful declined but could not be replaced because it was the end of the study. In total, 11 more successful and 12 less successful consumers participated (N=23). Most were Caucasian (N=20, 87%), and three (13%) were African American. Most were female (N=12, 52%). The mean age was 42.7±12.0.

Data were collected during the fall and winter of 2007. Researchers attended the team's morning meeting to invite staff participation. After obtaining informed consent, the consumer nominations were solicited and compiled. ACT staff contacted consumers first to determine their willingness to talk with a researcher. Researchers met individually with willing consumers to obtain written informed consent. Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed. Participants were compensated $50 for completing interviews. The Indiana University-Purdue University Institutional Review Board approved the study procedures.

To assess how staff view success and failure, staff reflected on the six exemplar consumers. Staff first rated the overall success of each consumer (1, completely unsuccessful, to 5, completely successful). We then asked, "What would make [consumer's name] a 5?" Or, "What would make [consumer's name] a 1?" Consumer interviews followed a similar process. Consumers first rated their own success in ACT using the same 5-point scale. We then asked, "What is it that would make you (or makes you) a 5?" and, "What is it that would make you (or makes you) a 1?" For both staff and consumers, additional probes were used for clarification. Interviews lasted 90 minutes and included questions from the larger study. Qualitative analyses followed a grounded theory approach (

10,

11 ). Three researchers separately and then jointly analyzed themes common across interviews. The labeling and organization of themes were aided by qualitative software (ATLAS.ti 5.5.9). We discuss differences in rank order (of at least four places) rather than frequency to account for varying verbosity between staff (average word count=76.2±22.2) and consumers (average word count=24.0±11.0).

Results

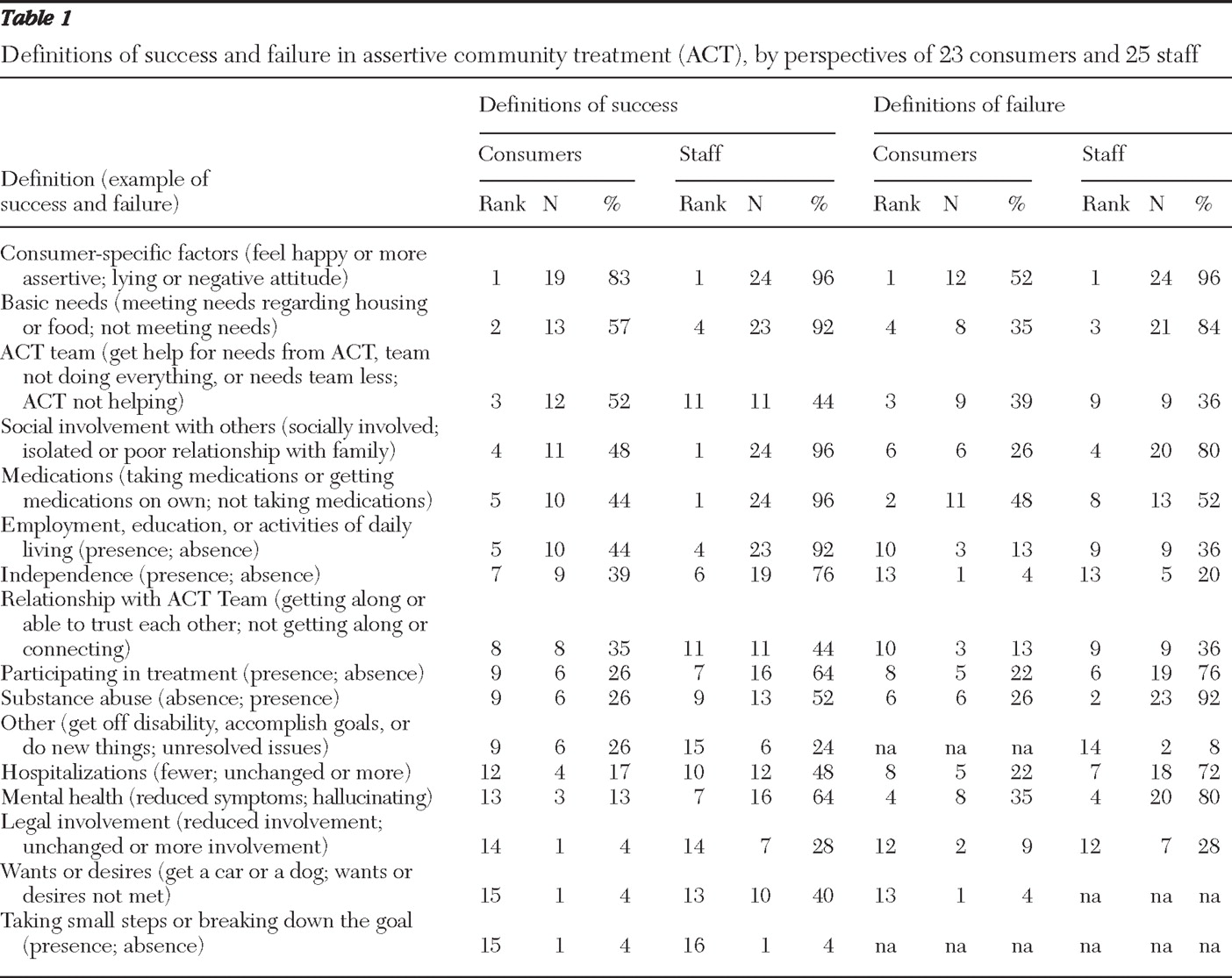

Themes and rankings are listed in

Table 1 . Rankings of staff and consumer definitions of success were correlated (r=.79, p<.01). There were several areas of strong agreement. First, for both, the top-ranked definition of success was consumer-specific factors—for example, behaviors (more assertive or less impulsive) and attitudes (feeling happy or increased confidence). For instance, one consumer stated, "I feel successful because I am independent. I am more assertive. I'm having a ball just meeting people." Staff and consumers also defined success according to consumers' social involvement (for example, reuniting with family and connecting with others) and meeting basic needs (for example, housing and food). Surprisingly, neither staff nor consumers emphasized reduced hospital use when defining success (tenth highest ranking by staff and 12th highest by consumers).

There were some notable differences between staff and consumer perceptions of success. Consumers described less need for ACT treatment when defining success (ranked third) ("They'd say, 'You are probably doing so good, we're going to let you go.'"), whereas staff ranked this relatively low (ranked 11th). For this category, consumers also described ACT processes that support success, such as getting needed help from the team (for example, help with finding housing). In contrast, staff mentioned improved mental health more often (tied for seventh) than consumers (ranked 13th). For example, staff described improvement in symptoms ("She's not as delusional and doesn't seem to be having the hallucinations") or broader mental health ("[The consumer] is just living his life and doing the things that he enjoys and being able to cope when he feels stressed").

Rankings of definitions of failure were correlated (r=.67, p<.05). Similar to the rankings of success, the top-ranked theme defining failure identified by both consumers and staff was consumer-specific factors—for example, undesirable behaviors (stealing, lying, negative attitudes, and not progressing in treatment). For instance, one staff member noted, "[The consumer] just makes a lot of bad decisions, really . . . it's just really poor judgment overall." And one consumer stated, "Because I haven't always tried, and I haven't always done my best, and I sometimes yell at people and have a negative attitude." Staff and consumers also defined failure according to poor social involvement (for example, lack of family support or isolated).

Surprisingly, when defining failure, not taking medications ranked second among consumers but only eighth among staff. One consumer stated, "So if I missed a few doses and pretty soon I would be sick, and I'd be not wanting to take it you know." Other consumers described failure as having to receive more medication supervision or not taking medications as prescribed. In contrast, staff ranked substance abuse higher (second) than did consumers (tied for sixth). For example, one staff member stated, "She's very much into her substance abuse right now, and that affects both her mental and physical health." In general, staff frequently linked substance abuse to difficulties with other areas of life (for example, "[He] lost his job, probably because of the substances.").

Finally, when discussing failure, consumers ranked the presence of negative aspects of ACT treatment higher (third) than did staff (tied for ninth), which included ACT not helping and staff controlling everything. For example, consumers stated, "I think they'd kick you out of the program" and "Well for me, it would be them controlling my money."

Discussion

Consistent with prior research comparing staff and consumer perspectives (

8,

9 ), we found similarities and differences in perspectives regarding success and failure. First, success and failure were defined most frequently by both groups in terms of consumer-specific factors. That is, both success and failure were viewed most often in terms of specific changes (for example, becoming more assertive) or lack of changes (for example, not progressing in treatment) in consumer attitudes and behaviors.

Across both staff and consumers, successes were more likely than failures to reflect client growth. That is, themes related to client growth (for example, relationships, employment, and independence) were ranked more highly as definitions of success than as definitions of failure. Success seemed to be viewed not just as the opposite of failure, but instead, embedded within it aspects of growth. The results also did not support concerns that ACT is inherently and narrowly focused on medical factors or symptom change.

Curiously, consumers were more likely than staff to mention not taking medications when defining failure, whereas staff were more likely than consumers to mention taking medications when defining success. Consistent with Deegan's work (

12 ), consumers viewed not taking medications as an undesirable outcome, but identified other types of "personal medicine" (that is, wellness strategies and activities) as indicators of success. Our finding that staff viewed taking medications as indicative of success corroborates previous literature in which case managers rated medication management as an extremely beneficial mechanism of action in ACT (

13 ). Another difference was that consumers were more likely to discuss helpful and unhelpful aspects of the ACT team. Consumers seemed to internalize external factors related to treatment, such as the need for and types of treatment received, in self-definitions of success and failure. In contrast, staff members were more likely to mention factors internal to the client, such as substance abuse, when defining failure and improved symptoms when defining success.

One striking finding was that hospitalizations were mentioned infrequently by staff and consumers, despite the emphasis within the ACT model on reducing hospitalizations. ACT programs have consistently demonstrated reduced hospitalizations over time (

2 ) and compared with other treatments (

3 ), suggesting that one critical indicator of ACT success is decreased hospitalizations. The findings presented here, however, suggest that ACT staff and consumers view treatment success and failure more broadly. Although reasons for the lower rankings were not clear, we speculate that hospitalization would be more salient to both groups if ACT was not successful in addressing this issue.

Staff and consumers emphasized social aspects of treatment. The impact of consumers' social relationships, both good and bad (for example, reuniting with family and isolating behaviors), was mentioned frequently when defining success and failure. This is consistent with findings that consumers view relationships as an important ingredient of ACT (

14,

15 ). However, ACT has not been effective in helping to develop friendships and family relationships (

1 ). These findings suggest that social relationships are valued within ACT, and further work should examine how ACT teams are facilitating or supporting these relationships.

Critically, our findings suggest that researchers need to broaden the view of success in ACT beyond hospitalizations to include other important aspects of treatment, such as medication adherence, relationships, consumer growth, and consumer-specific factors. Research reviews typically focus on hospital use and engagement rates, with some studies examining housing, employment, legal activity, symptoms, or quality of life (

1,

2,

3,

4 ). Our sample described a much richer view of treatment effectiveness.

Strengths of our study were the inclusion of both staff and consumers from several ACT teams and the use of open-ended interviews. We used the same coding scheme for staff and consumer interviews. Although different themes may have emerged if staff and consumers had been analyzed separately, we wanted to examine whether the presence or absence of themes varied between these two groups. Further analyses could also compare extreme groups of consumers (for example, those with severe levels of illness) or staff who fulfill different roles. One limitation is that themes reflect a broad level, resulting in several fairly heterogeneous themes (for example, consumer-specific factors) that could be broken down further in future analyses. In addition, future studies could benefit from examining a more racially, ethnically, and culturally diverse group, as well as a group with differences in prior hospitalizations and length of community tenure.

Conclusions

Understanding treatment success and failure helps identify the beneficial ingredients of ACT and aspects that could be modified to improve services. According to 48 staff and consumers, the critical factors in defining success and failure within ACT were most clearly related to consumer characteristics. Staff and consumers also identified broad aspects of treatment as critical to success and failure, including having basic needs met, being socially involved with others, and taking medications. There were differences between staff and consumers in their definitions of success and failure. Researchers should broaden their view of success in ACT beyond reduced hospitalizations to include domains such as social relationships and medication adherence.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by an Interventions and Practice Research Infrastructure Program grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (R24 MH074670; Recovery Oriented Assertive Community Treatment). The authors thank Angela Donovan, M.S., and Jennifer Lydick, B.S., for their assistance.

The authors report no competing interests.