Thirteen percent of the U.S. population is age 65 and over, and this proportion is expected to increase to 19 percent by 2025. Although elderly persons are a major focus of research in many areas of medicine, less is known about their mental health needs and service use.

Psychiatric disorders in the elderly population tend to be underdiagnosed, undertreated, and underresearched (

1,

2,

3). One reason for underdiagnosis and undertreatment is that individuals in this group are more likely to perceive psychiatric disorders as stigmatizing (

4) and may face greater barriers in gaining access to care. Providers also may be less informed about the identification and treatment of psychiatric disorders among elderly patients than among younger patients. Yet the high prevalence in the elderly population of psychiatric disorders such as dementia and depression suggest the importance of taking the mental health needs of this vulnerable subpopulation into account in structuring systems of care.

Ninety-five percent of elderly persons participate in the largest public health insurance program in the country, Medicare, which makes them an important population for mental health policy and mental health services research. Medicare is usually the primary payer for inpatient care of elderly persons, so it is responsible for setting policies that maintain a high quality of care while containing costs. One outstanding policy issue involves Medicare's reimbursement of psychiatric inpatient care provided by specialty hospitals and by general hospitals.

Medicare has traditionally distinguished between the care provided by psychiatric facilities and general hospitals. When Medicare changed from a cost-based system of hospital reimbursement to the prospective payment system in 1983, it exempted psychiatric hospitals and certain psychiatric units. These facilities are paid according to an alternative method based partly on historical costs, which provides less strict incentives for cost containment.

Although Medicare's hospital reimbursement policy appears to have favored specialty facilities, many psychiatric hospitals and units are expected to experience reductions in their 1998 Medicare payments as the result of provisions in the 1997 Balanced Budget Act. Furthermore, Medicare imposes a 190-day lifetime limit on coverage of psychiatric hospital care. This limit does not exist for psychiatric inpatient care provided in general hospital psychiatric units or general hospital nonpsychiatric beds. One likely effect of this limit will be to discourage Medicare beneficiaries, particularly those who are chronically ill and have already been hospitalized numerous times, from using psychiatric hospitals.

Past studies have shown that elderly Medicare beneficiaries are more likely to be treated in general hospital beds and less likely to be treated in psychiatric hospital beds than nonelderly disabled beneficiaries (

5,

6). Yet little else is known about the inpatient treatment patterns of the elderly population, or how these patterns vary across hospital types. Most data presented in earlier studies were averages across all diagnoses or the entire Medicare population. Elderly and disabled Medicare beneficiaries have very different clinical characteristics and patterns of use; thus few conclusions about the elderly as an individual population can be drawn from these studies. Other studies of the use of inpatient psychiatric care among elderly Medicare beneficiaries have focused on the impact of the prospective payment system on general hospital care.

The purpose of this observational study is to give a descriptive profile of the use of inpatient psychiatric care by elderly persons, based on administrative data from Medicare for all patients treated in both general and psychiatric nonfederal hospitals in the United States. We addressed four questions: How many elderly persons are hospitalized for a psychiatric disorder, for what conditions, and in what types of hospitals? How long are they hospitalized, and how much does it cost to care for them? To what level of care are they discharged? How do these patterns of care vary across hospital types?

Methods

Data sets used were the 1990-1991 Medicare inpatient standard analytic, denominator, and provider-of-service files and hospital cost reports.

Aggregate statistics on psychiatric hospitalizations and inpatient expenditures were based on all 1990 Medicare-covered inpatient admissions of elderly beneficiaries with a primary psychiatric diagnosis. The remaining analyses focused only on admissions to psychiatric hospitals, to psychiatric units within general hospitals, or to nonpsychiatric units in general hospitals. We defined psychiatric units as those applying for and meeting criteria for exemption from the prospective payment system (about two-thirds of all self-reported psychiatric units). We excluded about 10 percent of these stays from analysis because the beneficiaries were treated in federal hospitals, had a primary payer other than Medicare or had discontinuous coverage, participated in group health plans, or had inconsistent admission dates.

We first calculated psychiatric inpatient admission rates and the associated Medicare expenditures. Hospitalizations for psychiatric disorders were defined as those involving a primary ICD-9 diagnosis in the range of 290 to 319. Psychiatric disorders were aggregated into several categories: schizophrenic disorders, bipolar disorder, other psychotic disorders, major depressive disorder, other depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, dementia, organic disorders other than dementia, substance-related disorders, and all other disorders.

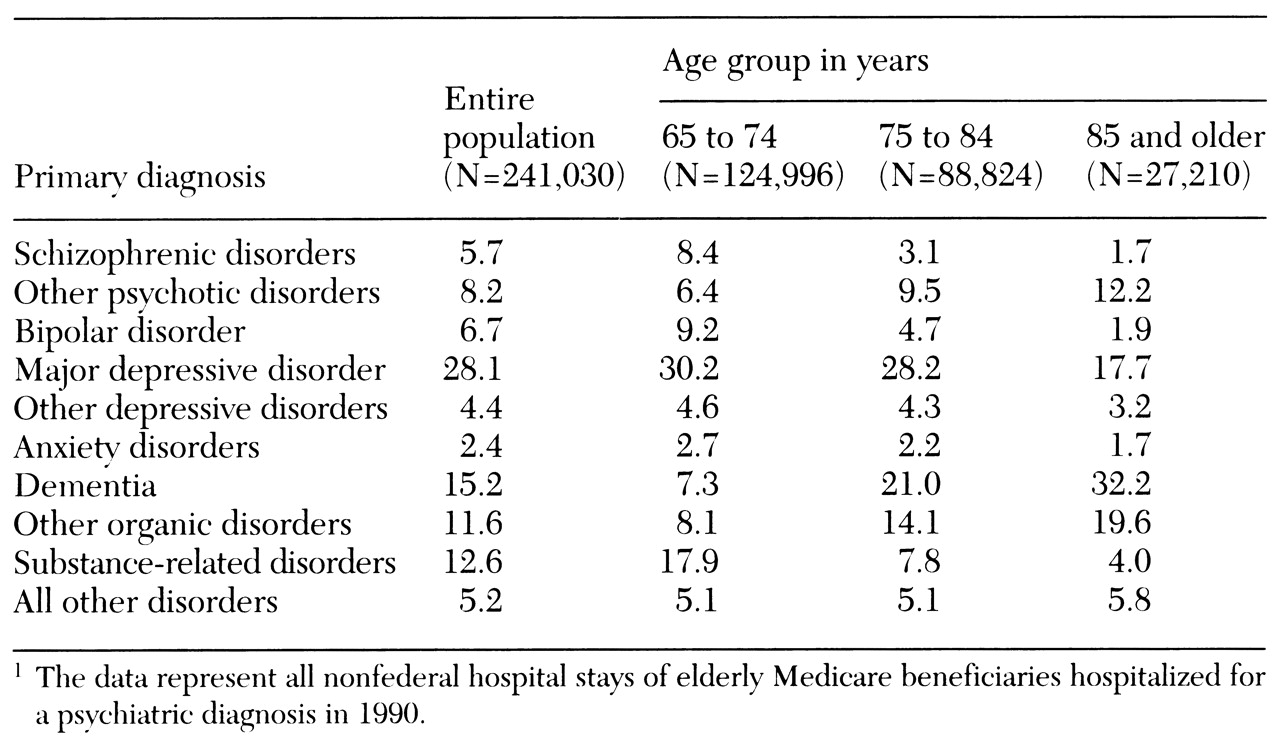

Next, we calculated the distribution of primary diagnoses by beneficiaries' age group (65 to 74 years, 75 to 84 years, and 85 and older) and the distribution of stays across hospital types, by age group and primary diagnosis.

Finally, we examined median lengths of stay (based on Kaplan-Meier models of days from admission to discharge), average costs, and discharge destinations by primary diagnosis and hospital type. Total costs for each hospital stay were constructed by adding up the hospital's or unit's total charges in each revenue center, multiplied by that center's cost-to-charge ratio. About 2 percent of stays were excluded from the cost analyses because no cost data were available. Several discharge destination categories were used: self-care at home, transfer to another hospital, transfer to a nursing home, and all other (including home care, death, and departure against medical advice).

Although statistical tests are not strictly necessary because our analyses are based on the entire population rather than a sample, chi square and F tests showed all differences across subgroups to be significant at p<.001.

Results

The research questions

How many elderly Medicare beneficiaries are hospitalized for a psychiatric disorder?

During 1990 a total of 192,194 elderly Medicare beneficiaries were hospitalized at least once because of a primary psychiatric diagnosis, for a total of 245,135 psychiatric hospitalizations. The average age of these inpatients was 75 years. Sixty-four percent were women, and 88 percent were white.

The mean Medicare payment per elderly person hospitalized for a psychiatric disorder was $5,637, for total program expenses of more than $1 billion for inpatient psychiatric stays of elderly patients. Expenditures for psychiatric inpatient stays constituted about 2 percent of the $53.4 billion total Medicare expenditures for all hospitalizations of elderly persons in 1990 (

7).

For what psychiatric conditions are elderly persons hospitalized?

Table 1 shows the distribution of primary diagnoses among elderly Medicare beneficiaries in each age group who were hospitalized for a psychiatric diagnosis. Among all elderly beneficiaries combined, the most common diagnoses coded as the reason for hospitalization were major depressive disorder (28.1 percent), dementia (15.2 percent), substance-related disorders (12.6 percent), and organic disorders other than dementia (11.6 percent). Thus major depression and organic disorders together accounted for almost two-thirds of the psychiatric inpatient stays of the elderly beneficiaries, although substance-related and psychotic disorders were also common reasons for hospitalization. Schizophrenia was the primary diagnosis for almost 6 percent. Additional analyses revealed that about a third of the elderly patients hospitalized for schizophrenia originally qualified for Medicare on the basis of disability.

With increasing age, the diagnostic distribution was found to change. As expected from the dramatic increase in the prevalence of dementia with age, much higher proportions of the elderly beneficiaries in the upper age categories were treated for a primary diagnosis of dementia or another organic disorder. More than half of the inpatient psychiatric stays among those aged 85 and older were for treatment of an organic disorder. The increase in the frequency of organic disorders among the oldest old was accompanied by a reduction in the frequency of most other diagnoses. A notable exception was the increase with age in the frequency of psychotic disorders other than schizophrenia, which may reflect psychotic presentations secondary to dementia and other organic conditions.

Where are elderly persons treated for psychiatric disorders?

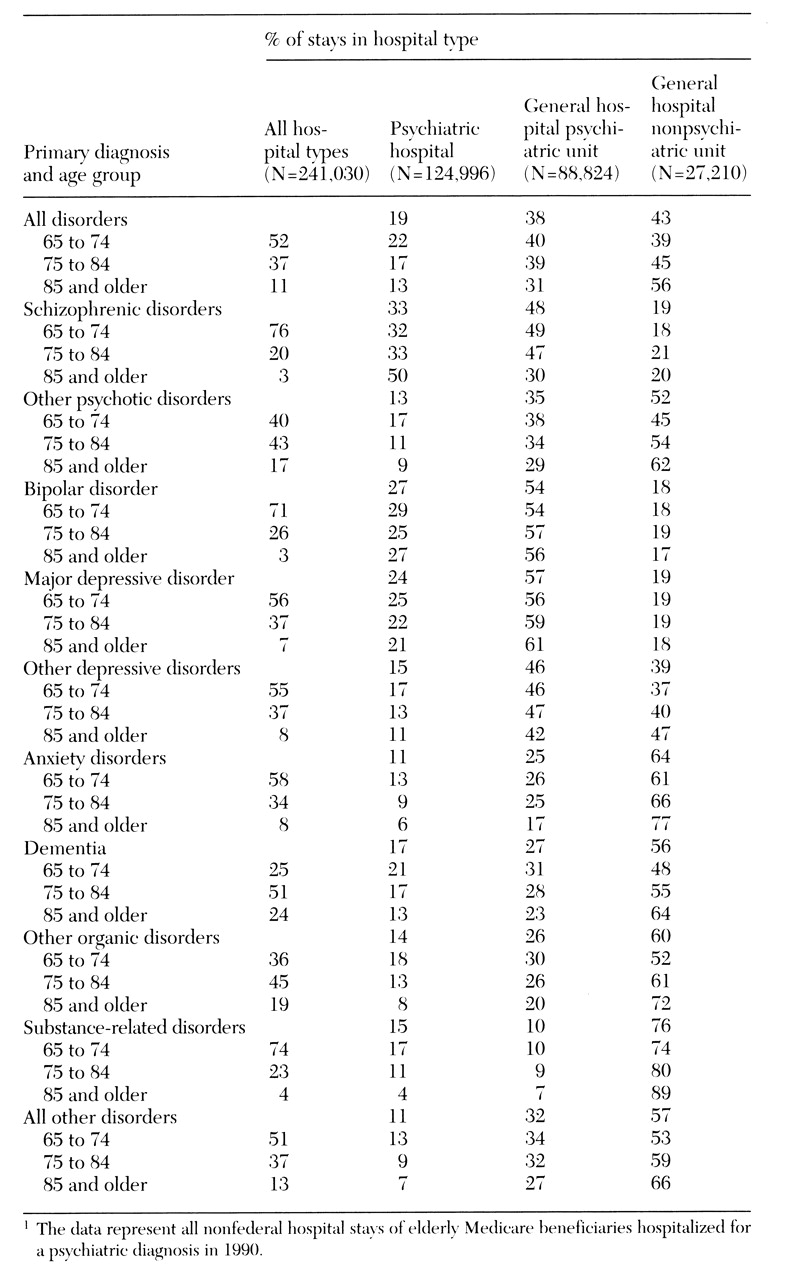

Table 2 shows the percentage of psychiatric inpatient stays that occurred in psychiatric hospitals, general hospital psychiatric units, and general hospital nonpsychiatric units by primary diagnosis and age group. Relatively few of the hospitalized elderly beneficiaries were treated in psychiatric hospitals (19 percent). Patients with schizophrenic disorders, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder were the most likely to receive inpatient treatment in a psychiatric hospital. Those with anxiety disorders and substance-related disorders and those in the "all other disorders" category were the least likely to be treated in a psychiatric hospital.

General hospital psychiatric units were the most common setting for elderly patients with primary diagnoses of schizophrenic disorders, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. For all other elderly beneficiaries, general hospital nonpsychiatric beds were the most common setting. Certain age-related patterns emerged. Among beneficiaries with all but the most severe diagnoses (schizophrenic disorders, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder), older patients were more likely than younger ones to be treated in a general hospital and less likely to be treated in a psychiatric hospital.

Length of stay

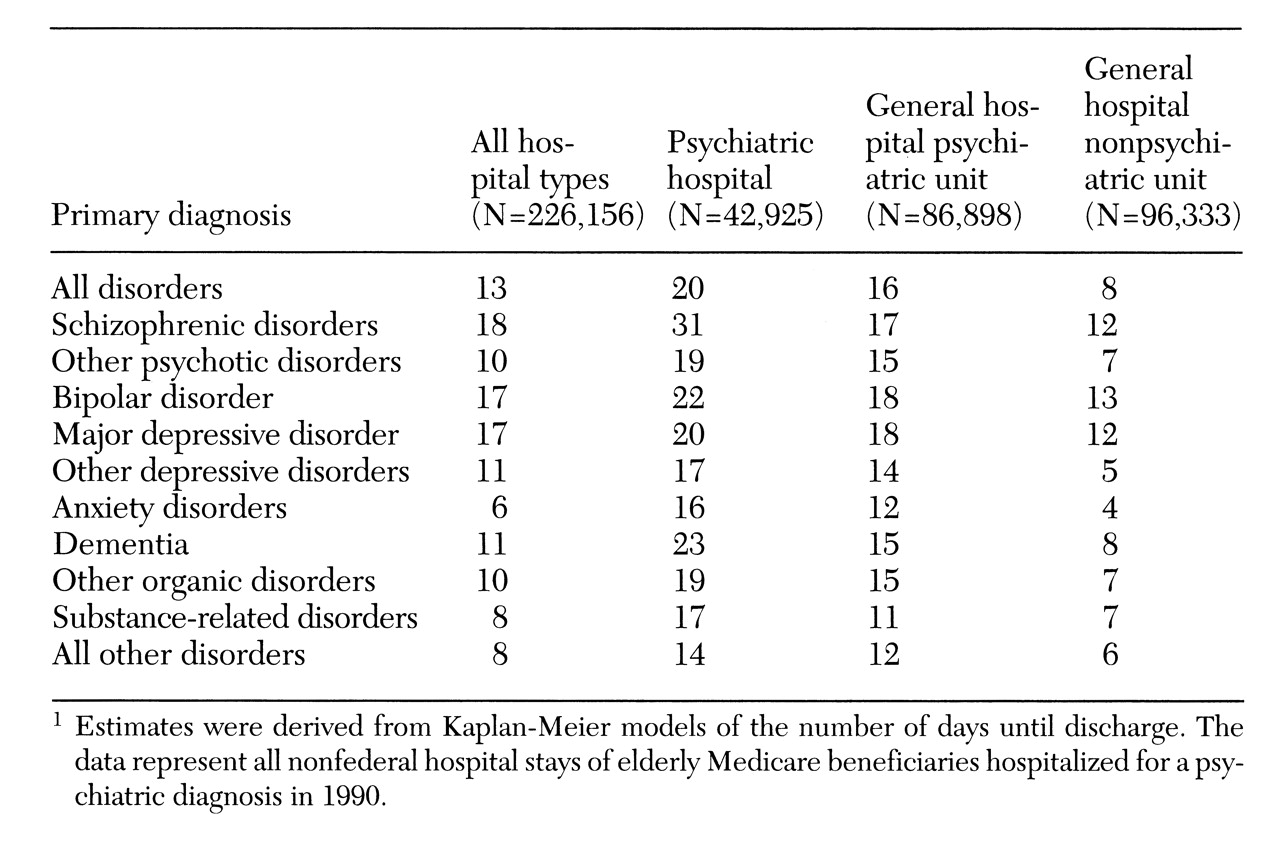

Table 3 presents median lengths of stay by primary diagnosis and hospital type. Lengths of stay varied substantially across subgroups. Within each diagnostic category, median lengths of stay were uniformly shorter in general hospital nonpsychiatric beds than in general hospital psychiatric units, and shorter in general hospital psychiatric units than in psychiatric hospitals. For example, among elderly beneficiaries hospitalized for schizophrenic disorders, the median length of stay was 12 days in general hospital beds, 17 days in psychiatric units, and 31 days in psychiatric hospitals.

Costs

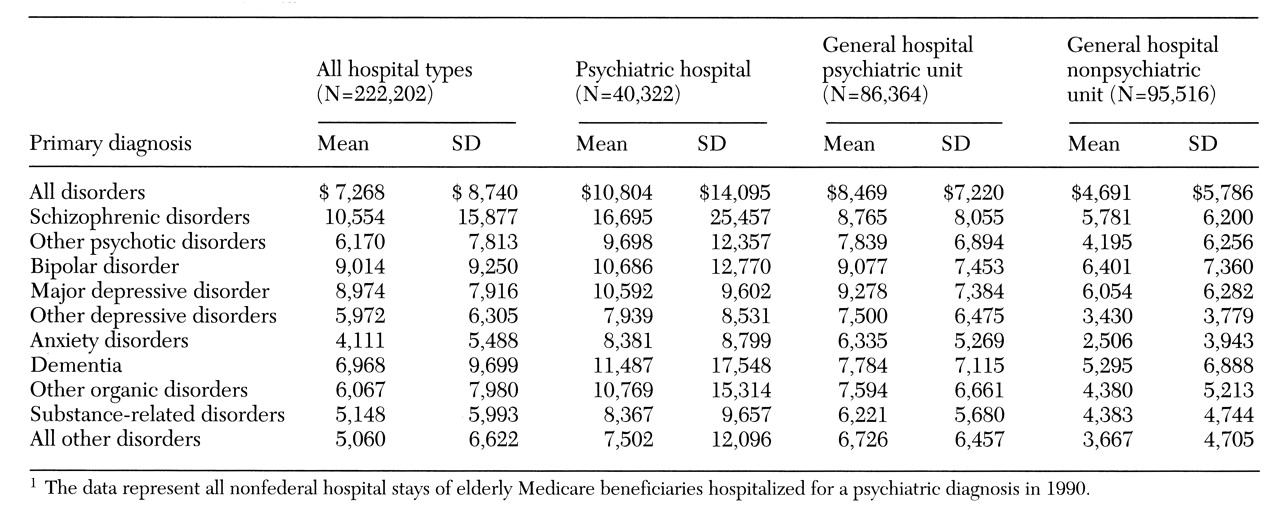

Table 4 shows the mean costs of inpatient stays. As with length of stay, costs per stay varied by diagnostic category and hospital type. Costs were uniformly highest in psychiatric hospitals and lowest in general hospital nonpsychiatric beds. However, additional analysis showed that with the exception of costs associated with affective disorders, average daily costs were actually lower in psychiatric hospitals than in general hospital psychiatric units or general hospital nonpsychiatric units. This result could be explained either by declining intensity of inpatient treatment over time or lower medical comorbidity among elderly patients admitted to psychiatric hospitals.

Discharge destinations

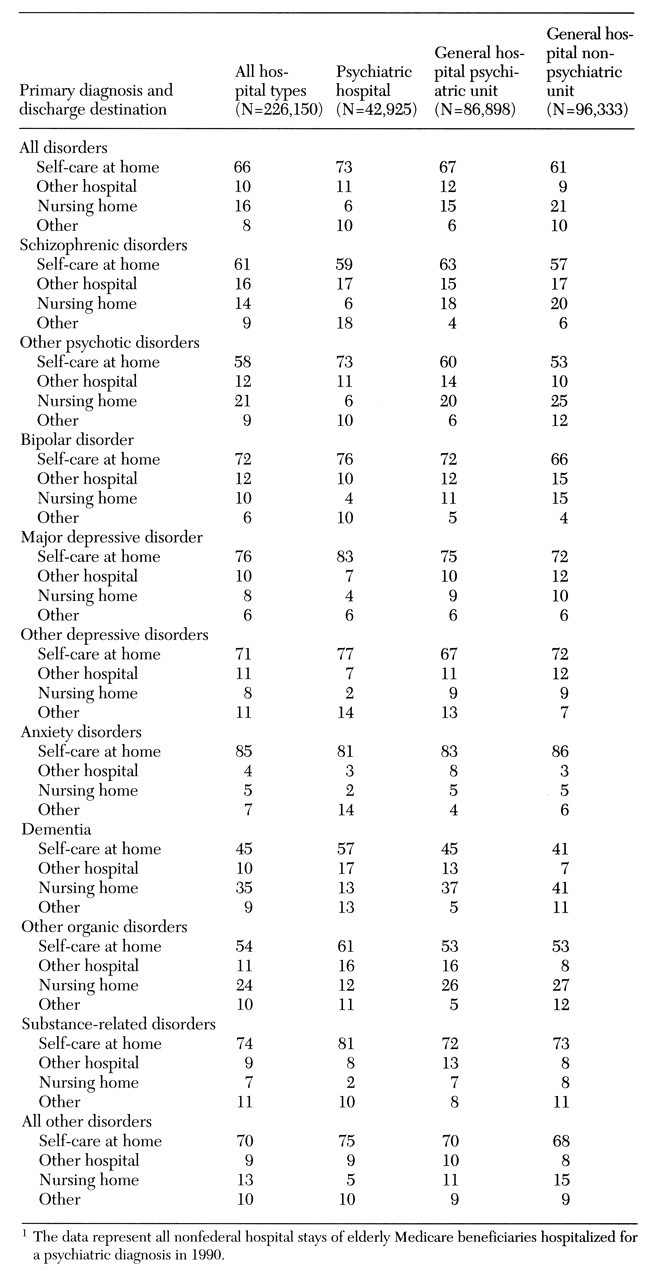

Table 5 gives the frequency distributions of discharge destination by primary diagnosis and hospital type. Among all hospital types, elderly patients with dementia and other organic disorders generally had the lowest rates of discharge to self-care compared with other diagnostic groups, probably due to their inability to adequately care for themselves. Elderly patients with schizophrenic disorders and other psychotic disorders also had low rates of discharge to self-care. The highest rates of discharge to self-care were found among those hospitalized for anxiety disorders, major depressive disorder, and substance-related disorders.

Substantial differences in discharge destinations were found across hospital types. Among all beneficiaries except those with schizophrenic disorders and anxiety disorders, rates of discharge to self-care were highest for those treated in psychiatric hospitals. In all cases, rates of discharge to nursing homes were lowest in psychiatric hospitals and highest in general hospital nonpsychiatric units, with general hospital psychiatric units generally in between.

For example, only 41 percent of the stays for dementia that occurred in general hospital nonpsychiatric units resulted in the patient's being discharged to self-care. In contrast, 57 percent of stays for dementia in psychiatric hospitals resulted in discharge to self-care. The rate was 45 percent for general hospital psychiatric units. The higher rates of discharge to self-care among patients with dementia treated in psychiatric hospitals were associated with substantially lower rates of discharge to nursing homes—13 percent of patients in psychiatric hospitals were discharged to nursing homes compared with 37 percent from general hospital psychiatric units and 41 percent from general hospital nonpsychiatric units.

The high rates of discharge to nursing homes from general hospital nonpsychiatric units do not appear to be the result of patients admitted from nursing homes returning to them on discharge. A separate analysis (data not shown) found higher rates of discharge to nursing homes from general hospitals regardless of admission source.

Discussion and conclusions

In 1990 the total number of U.S. residents aged 65 and over was 31.2 million (

8). Of these, 30.5 million had Medicare part A (inpatient) coverage, representing the vast majority of elderly Americans (

7). Elderly Medicare beneficiaries had more than 240,000 inpatient psychiatric stays in 1990. About .6 percent of elderly Medicare beneficiaries were hospitalized for a primary psychiatric disorder at least once during 1990. The data presented in this study provide a descriptive profile of their inpatient treatment patterns.

Among the entire population of elderly Medicare beneficiaries treated for psychiatric disorders, the median length of stay was 13 days, and the average cost per hospital stay was $7,268. Only about two-thirds of these hospital stays ended with the patient's being discharged to self-care. A tenth of all psychiatric hospitalizations ended with the patient's being transferred to another hospital, and a sixth ended with discharge to a nursing home.

About 43 percent of the 1990 hospital stays of elderly Medicare beneficiaries treated for psychiatric disorders occurred in general hospital nonpsychiatric beds, 38 percent in general hospital psychiatric units, and only 19 percent in psychiatric hospitals. Even among elderly patients with diagnoses indicative of severe mental illness, such as schizophrenic disorders, major depressive disorder, and bipolar disorder, almost a fifth of hospital stays occurred in general hospitals.

Medicare databases are unlikely to include data for psychiatric hospital stays paid for out-of-pocket or by other insurers after the beneficiary exceeds Medicare's lifetime limit on coverage. Thus the proportion of all psychiatric inpatient stays that occurred in psychiatric hospitals is probably understated here. Yet even in comparison with rates of disabled Medicare beneficiaries, rates of psychiatric hospital use by elderly persons are quite low, particularly among the oldest old.

Elderly beneficiaries treated in general hospitals may be less severely ill on average than those treated in psychiatric hospitals or units. We did not have measures of severity of illness within diagnostic category. In addition, given the high rates of medical comorbidity among elderly persons treated for psychiatric disorders, the extensive use of general hospitals and less frequent use of psychiatric hospitals may be appropriate. However, it may also be that low rates of psychiatric hospital use result in part from the lifetime limit on coverage imposed by Medicare. Geographic inaccessibility, limited transportation options, and perception of stigma are other possible barriers to obtaining care at psychiatric hospitals faced by elderly persons (

4).

Past studies provide limited evidence about differences in care between psychiatric hospitals, general hospital psychiatric units, and general hospital nonpsychiatric units. Dorwart and Hoover (

9) found that psychiatric hospitals provide better follow-up care than general hospital psychiatric units. Norquist and associates (

10) and Wells and colleagues (

11) showed that the quality of psychological care is higher but the quality of medical care is lower in psychiatric units than on general medical wards. If the specialized resources available in psychiatric facilities are necessary for high-quality mental health care and are not provided to the same extent by general hospitals, then in choosing providers elderly patients may be confronted with a tradeoff between the quality of their psychiatric inpatient care and that of their medical inpatient care.

We identified substantial differences in resource use among elderly patients treated in psychiatric hospitals, general hospital psychiatric units, and general hospital nonpsychiatric units. Within all diagnostic categories, lengths of stay and total costs per stay were lower in general hospitals than in psychiatric hospitals and units. The value of longer lengths of stay in terms of improving outcomes is controversial (

12,

13,

14), and total costs do not provide information about the type or appropriateness of services received. Furthermore, the ability to describe a patient's clinical status based on claims data is limited (

15).

Further research is needed to explore the extent to which severity of illness within a diagnostic category can explain differences in resource use. Differences in other population characteristics, such as the availability of family support, may also contribute to variation in the costs of care across hospital types.

Yet if the difference in costs between psychiatric inpatient stays in general hospital beds and those occurring in specialty psychiatric facilities remains substantial after further adjustment for population characteristics, one interpretation might be the effects of the reimbursement system. In contrast to its reimbursement of care provided in psychiatric hospitals and exempt units, Medicare pays general hospitals prospectively, so that they generally retain any cost savings achieved, but they also incur losses. Thus psychiatric facilities have less incentive to be cost-efficient, yet also less incentive to cut back on services or discharge patients earlier to save money.

Further exploration of whether utilization differences by hospital type are attributable to unmeasured case-mix or differential disease management is beyond the scope of the current study. Nonetheless, the data do provide evidence consistent with several hypotheses about differences in treatment patterns between hospital types. For example, among beneficiaries admitted for organic, affective, and psychotic disorders other than schizophrenia, those treated in general hospitals had shorter lengths of stay, higher rates of discharge to nursing homes, and lower rates of discharge to self-care at home than those treated in psychiatric hospitals, even when the analysis controlled for admission source.

One possible explanation is that elderly patients treated in general hospitals have less severe psychiatric disorders, resulting in earlier discharges, and greater medical comorbidity, preventing them from being discharged to self-care yet making them more acceptable to nursing homes. Other possibilities include that social service departments in general hospitals and psychiatric hospitals may differ in their use of nursing homes, as well as in the use of mental health treatment resources such as residential programs or group homes.

Another explanation is that longer lengths of stay facilitate discharge to home, either because patients are healthier at discharge or because families have more time to make informal caregiving arrangements. General hospitals may be substituting nursing home care for their own services; patients can be discharged sooner from acute care settings if they are provided with alternative forms of care. Substitution could be a cost-effective strategy that achieves similar outcomes at a lower cost by replacing expensive hospital inpatient care with less expensive nursing home care. Alternatively, substitution could represent pure cost-shifting, resulting in similar or higher total costs of care while having potentially adverse effects on continuity of care and patient outcomes. Additional analyses are needed to evaluate these competing views.

These data provide a number of insights into the diagnostic composition and service utilization of the elderly Medicare population. Not surprising was the finding of the high proportions of psychiatric inpatients with a primary diagnosis of major depression or dementia, given the high prevalence of these conditions in the elderly population. Among the oldest old, the high proportion of patients with a primary diagnosis of dementia or another organic condition—more than 50 percent of the hospitalized population—should prompt consideration of whether Medicare provides appropriate reimbursement and coordination of care to meet the needs of this population.

The significant proportions of patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and substance-related disorders illustrate that elderly patients requiring inpatient psychiatric services have primary psychiatric diagnoses, and they are not admitted just for treatment of disorders commonly acquired in later years, such as dementia. The elderly psychiatric population includes a substantial proportion of patients with chronic or relapsing disorders that commonly first appear in earlier years. Even though patients with severe mental illness have shorter average life spans than the general population, many patients with severe mental illness live to older ages and must be considered by Medicare policy makers.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant R29 MH53698-01).