Bipolar disorder affects 1 to 1.5 percent of the general population of the United States (

1), and the overall economic burden of bipolar disorder in the U.S. has been estimated at $45 billion per year (

2). Most available epidemiologic data on treatment of bipolar disorder have come from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study. This community survey estimated that approximately 55 percent of persons with bipolar disorder received some treatment in a year, and that approximately 33 percent saw mental health specialty providers (

1,

3). Those receiving outpatient specialty care made an average of about 14 visits in a year. The proportion receiving any inpatient care during one year was approximately 7 percent of those affected by bipolar disorder and approximately 13 percent of those receiving any treatment.

The study reported here used administrative data from a large health plan to examine patterns of utilization of health services by patients treated for cyclothymia, bipolar disorder, or schizoaffective disorder and costs of those services. Patients were identified using computerized records of prescriptions filled, diagnoses for outpatient visits, and inpatient discharge diagnoses. Comparison groups matched by age and sex in the health plan were selected from a sample of general medical outpatients as well as from samples of patients treated for depression and diabetes. Utilization and cost data were extracted from the health plan's computerized cost-accounting records.

Our objectives were to examine health care costs from the insurer's perspective for a population-based sample of patients with bipolar disorder, compare costs for the bipolar disorder group with those for age- and sex-matched samples of patients treated for diabetes and depression, and examine how specialty mental health service utilization and out-of-pocket costs were distributed across the population treated for bipolar disorder.

Methods

Study setting

The Group Health Cooperative of Puget Sound is a large staff-model health maintenance organization (HMO) that serves approximately 450,000 residents of western Washington State. The company provides comprehensive care on a capitated basis, and members typically receive their coverage through employer-subsidized plans.

The Group Health Cooperative includes approximately 45,000 Medicare members and 35,000 members covered by Medicaid or by Washington's Basic Health Plan, a state program for low-income residents. Group Health Cooperative members are similar demographically to Seattle area residents, except that the members have a higher average educational level and include fewer high-income residents (

4). More than 90 percent of the primary care physicians and psychiatrists who provide services through the Group Health Cooperative are certified by the appropriate specialty boards. All mental health and general medical providers are paid by salary, with no individual financial incentives tied to utilization or referral patterns.

Six outpatient specialty mental health clinics emphasize short-term individual psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and group therapy. Approximate numbers of full-time-equivalent clinical staff per 100,000 members are as follows: 5.5 psychiatrists, 2.5 psychiatric nurse practitioners, 2.5 psychiatric nurses, 2.5 psychologists, and 15 master's-level psychotherapists. These staffing levels are similar to those at other group-model or staff-model health plans (

5).

Although the intensity or duration of treatment is not limited by any formal authorization or review process, providers typically allocate available time according to the patient's severity of illness and urgency of presentation. Typical coverage arrangements for outpatient psychotherapy allow ten to 20 visits per year that are subject to visit copayments between $10 and $20. Psychiatric visits for medication management are covered at parity with general medical visits; both types of visits have the same copayment level and no annual limits. No referral or authorization is required for seeking specialty mental health care, and primary care physicians have no financial incentive to limit mental health service use.

Inpatient mental health services are provided by facilities that are not part of the Group Health Cooperative. These facilities are paid on a fee-for-service basis. Most inpatient care occurs at facilities contracted to provide inpatient care at a fixed daily charge. Prior approval is required for all hospitalizations, and length of stay is closely managed by concurrent review. Typical Group Health Cooperative coverage arrangements for inpatient care provide for 14 to 30 days of treatment per calendar year with coinsurance rates of 10 to 20 per cent.

The HMO's computerized information systems include data on all outpatient visits to clinics in the HMO and all outpatient prescriptions filled at pharmacies affiliated with the HMO. Previous surveys of Group Health Cooperative members have found that more than 95 percent of the prescriptions filled by members—including those for antidepressant drugs—are filled at pharmacies affiliated with the HMO (

6).

Identifying patients treated for bipolar disorder

Potential subjects were all adult members of the Group Health Cooperative who were enrolled in the health plan at any time during the study period, which was from July 1, 1995, to June 30, 1996. Details about this sample, including methods of identification, sources of insurance coverage, and sources of treatment, are described in an earlier publication (

7) and will be summarized here.

We identified members with possible bipolar disorder using three criteria: any inpatient discharge diagnosis in the bipolar spectrum, including bipolar disorder, cyclothymia, and schizoaffective disorder; any outpatient-visit diagnosis in the bipolar spectrum; or any filled prescription for a mood stabilizer such as lithium, carbamazepine, and valproate that was not associated with a diagnosis of seizure disorder or written by a neurologist. A review of a random sample of medical records indicated that the diagnosis of bipolar disorder was generally confirmed, with a false-positive rate under 10 percent, in the following three subgroups of patients: those with an inpatient diagnosis of bipolar disorder, those with an outpatient diagnosis from a mental health provider, and those who had a diagnosis from another provider, such as a primary care provider, and who had a prescription for a mood stabilizer. These patients were included in the final sample.

The diagnosis of bipolar disorder was generally not confirmed, with a false-positive rate of more than 50 percent, among patients who had a diagnosis from a nonpsychiatrist but who did not have a prescription for a mood stabilizer and among patients who had a prescription for a mood stabilizer from a nonpsychiatrist but who did not have a diagnosis of bipolar disorder. These subgroups were excluded from the final sample. One additional subgroup—patients with a prescription for a mood stabilizer from a psychiatrist but without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder—included roughly equal numbers of patients with and without confirmable diagnoses. Treating psychiatrists were contacted to definitively classify the patients in this subgroup.

For each patient in the bipolar disorder group, we defined an index date equal to the date of the first treatment event—prescription, visit, or hospitalization—during the study period. The group was then limited to patients who were continuously enrolled in the health plan for at least six months after the index date.

Identification of comparison groups

Following a procedure identical to that used to identify patients treated for bipolar disorder, we selected three population-based comparison groups from the remaining population of HMO members with no bipolar diagnosis or mood stabilizer prescription during the study period. The first group, the general outpatient sample, included all adult members who made one or more outpatient medical visits during the study period. The second group included all adult members receiving an inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of diabetes during the study period. The third group included all adult members receiving an inpatient or outpatient diagnosis of depressive disorder during the study period.

For each member in these samples we defined an index date based on the first treatment event—any outpatient visit for the general outpatient sample, any diagnosis of diabetes for the diabetes sample, and any diagnosis of depression for the depression sample. Each sample was then limited to those continuously enrolled for at least six months after the index date.

Age and sex distribution differed widely across the four groups. To eliminate potential confounding effects of age and sex—both strong predictors of general medical and mental health care utilization—each comparison group was frequency-matched with the bipolar disorder group on these factors.

Utilization and cost data

For each patient in the bipolar disorder group or the comparison groups, we examined use and cost of all health care services covered by the Group Health Cooperative for the six months after each individual's index date. Data were extracted from the HMO's computerized cost accounting system (

8). This system tracks each unit of service, such as an outpatient visit, a prescription, or an inpatient day, that is provided or paid for by the health plan.

For services produced by the health plan, including outpatient visits, diagnostic testing, and hospitalization at the HMO's facilities, the system estimates actual cost of production. Each service center—outpatient clinic, laboratory, or pharmacy—must allocate actual costs of operation to each unit of service provided. Health plan administrative costs are distributed proportionally across service centers. For services purchased from external providers and reimbursed by the health plan—all psychiatric hospitalization, drugs, and specialty services not provided by the HMO—the accounting system records the amount actually paid. In most cases, this amount paid to external providers reflects contracted prices negotiated by the Group Health Cooperative rather than the providers' customary charges. This system also accounts for patients' out-of-pocket contributions (copayments or coinsurance) so that the final cost estimates reflect the health plan's actual expenses.

In summary, data from this system reflect the health plan's actual costs of providing health care services, that is, cost from the insurer's perspective. For patients treated for bipolar disorder, claims records were reviewed to identify claims or portions of claims for inpatient mental health care that were not paid by the health plan because of coinsurance or annual coverage limits. This strategy allowed us to estimate costs of treatment in this group if inpatient psychiatric care had been covered "at parity" with general medical care.

Data analyses

As in previous studies, the health services cost data showed highly skewed distributions. All categories of cost were highly skewed to the right due to the large number of high-cost outliers. Many cost categories, such as inpatient care, had large numbers of nonusers. Although we present true means and standard deviations, statistical tests of differences between groups required appropriate transformation. For categories showing an approximately log-normal distribution, including total cost and total general medical cost, statistical tests were conducted on the log scale. For categories with a large number of nonusers—such as costs for specialty mental health and substance abuse services—tests were based on rank transformation using the Mann-Whitney test.

Given the large number of comparisons due to the use of multiple categories of cost and three comparison groups, a threshold of p<.01 was adopted for assessing statistical significance. Analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows software.

Results

Study sample

Of the 1,346 patients in the bipolar disorder sample, 66 percent were female. The mean±SD age was 43±14 years, with a range from 18 to 89 years. A detailed description of the treated sample is given in an earlier publication (

7). By virtue of the matching procedure, all three comparison groups showed identical distributions of age and sex.

Comparisons of overall health care costs

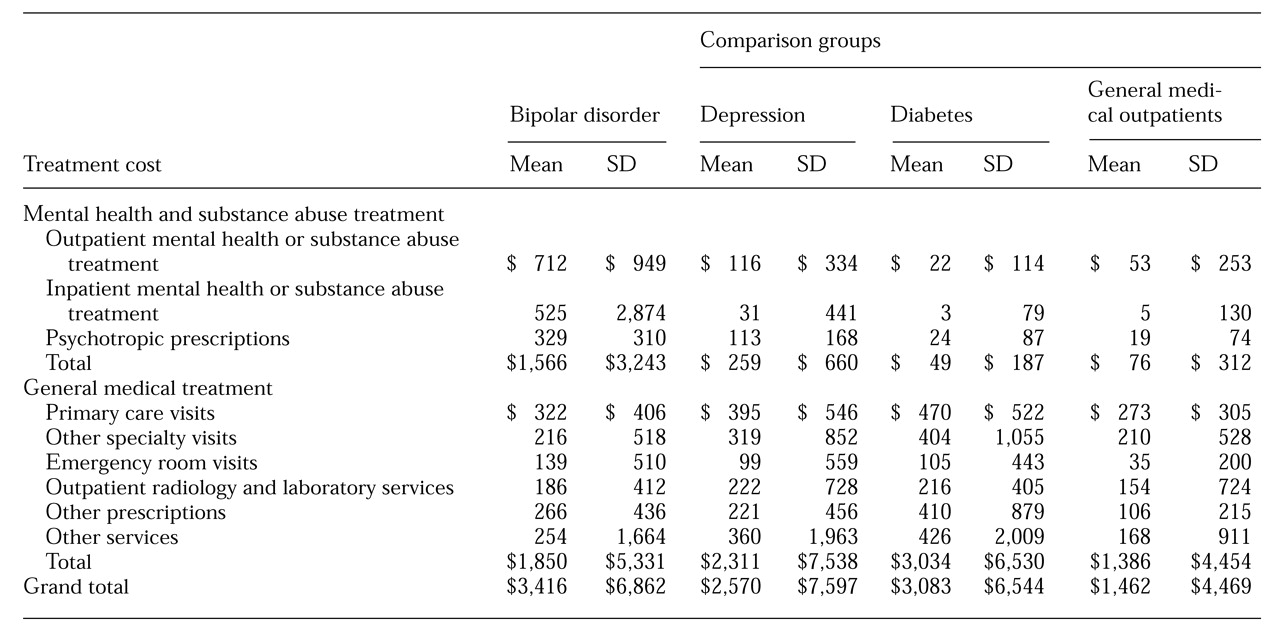

Table 1 shows costs over a six-month period for the bipolar disorder sample and for the three comparison groups. Mean costs for all specialty mental health or substance abuse treatment among patients treated for bipolar disorder were approximately six times as high as those for patients treated for depression and 20 times as high as those for the other comparison groups. Specialty mental health care accounted for approximately 45 percent of total costs in the bipolar disorder group, compared with 10 percent in the depression group and 5 percent or less in the other groups.

Comparisons using Mann-Whitney tests confirmed that the bipolar disorder group had significantly higher mental health and substance abuse treatment costs than the depression comparison group (Z=32.4, p<.001), the diabetes comparison group (Z=43.3, p<.001), and the general outpatient comparison group (Z=42.3, p<.001). General medical treatment costs for the bipolar disorder group were higher than those for the general outpatient sample but lower than those for the depression or diabetes comparison groups.

Comparisons on the log scale indicated that general medical costs in the bipolar disorder group were significantly higher than those in the general outpatient group (t=3.53, df=2,690, p<.001), significantly lower than those in the diabetes group (t=11.98, df=2,690, p<.001), and not significantly different from those in the depression comparison group. Although general medical costs appeared higher in the depression group than in the bipolar disorder group, this apparent difference was the result of a few high-cost outliers in the depression group. Total health care costs were highest among patients treated for bipolar disorder, and comparisons on the log scale found that total costs in the bipolar disorder group were significantly higher than those in the depression comparison group (t=11.34, df=2,690, p<.001), those in the diabetes comparison group (t=6.95, df=2,690, p<.001), and those in the outpatient comparison group (t=24.49, df=2,690, p<.001).

To determine what portion of general medical utilization might be attributable to treatment of mood disorder, we examined the frequency of primary care visits and emergency room visits that were associated with a mental health diagnosis in the depression and bipolar disorder groups. In the bipolar disorder group, approximately 15 percent of visits were associated with a mental health diagnosis and an additional 10 percent were associated with both a mental health and a general medical diagnosis. In the depression group, the corresponding proportions were 15 percent and 15 percent.

Utilization in the bipolar disorder group

As

Table 1 shows, outpatient mental health and substance abuse specialty care accounted for approximately 45 percent of all mental health and substance abuse costs, with inpatient care and psychotropic prescriptions accounting for 34 percent and 21 percent, respectively.

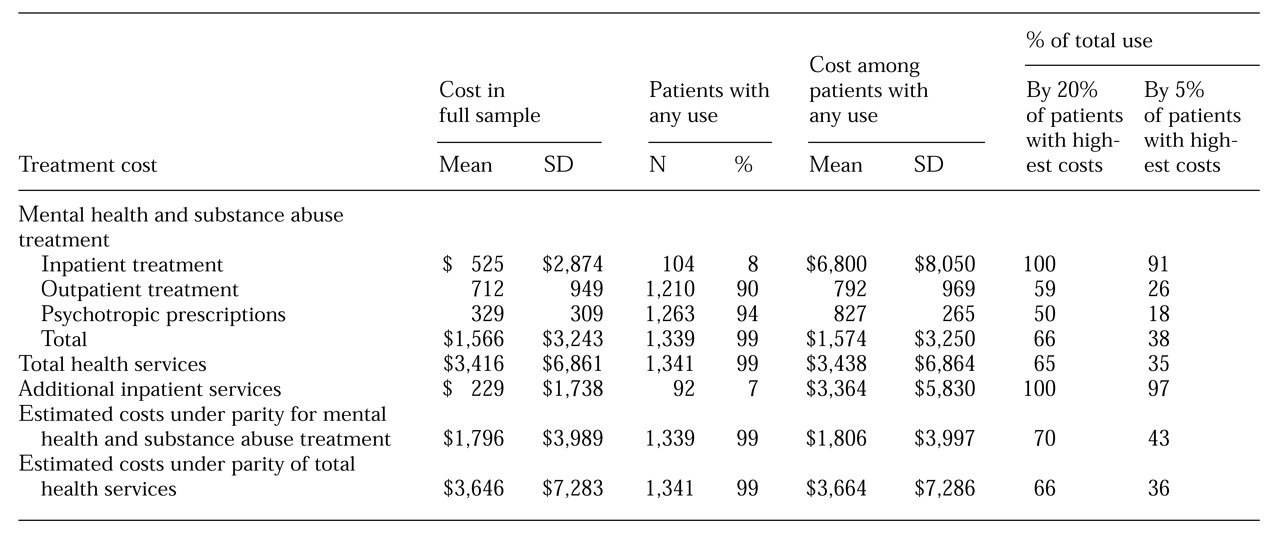

Table 2 provides additional details of utilization by patients treated for bipolar disorder. Different categories of specialty mental health and substance abuse treatment showed markedly different distributions within the group of patients treated for bipolar disorder. Inpatient costs were concentrated in a small portion of patients. Only 8 percent of patients used any inpatient services, and the 5 percent of patients with the highest costs accounted for 91 percent of all inpatient costs.

Outpatient visit costs for patients with bipolar disorder showed a less extreme pattern, but the distribution of costs among those using outpatient services was still skewed due to a large number of high-cost outliers, and the standard deviation was larger than the mean. Psychotropic prescription costs were the most evenly distributed; the 5 percent of patients with the highest costs accounted for only 18 percent of total expenditures.

Table 2 also presents data on additional inpatient charges that were not paid by the health plan. The sum of these charges was equal to 43 percent of the total inpatient charges covered by the health plan. As expected, these charges showed an extreme distribution. Only 7 percent of users had any additional inpatient charges, and the standard deviation among users was nearly twice the mean. The median value for additional inpatient charges was $987. Further analyses of individual inpatient admissions found that hospital stays longer than 30 days accounted for only 5 percent of all admissions but 36 percent of all additional charges. Twenty-one percent of all additional charges were attributable to 12 extended stays in state hospitals.

The bottom rows of

Table 2 illustrate how specialty mental health and substance abuse treatment expenditures and overall expenditures would be affected if these additional charges were borne by the insurer—that is, if mental health inpatient care were covered at parity with general medical care.

Discussion and conclusions

These data help clarify patterns of utilization among insured patients treated for bipolar disorder. The distribution of treatment expenditures was highly skewed, with one-fifth of patients accounting for two-thirds of the specialty treatment costs. Total health care costs for the bipolar disorder group were higher than those of patients treated for depression or diabetes, with costs for specialty mental health and substance abuse services accounting for the difference.

Only limited data on treatment costs of patients with bipolar disorder are available for comparison. Wyatt and Henter (

2) estimated that inpatient, outpatient, and medication costs for U.S. patients with bipolar disorder were approximately $2.35 billion for inpatient care and $700 million for outpatient visits and medication in 1991. Dividing this total by the estimate of 600,000 U.S. residents treated for bipolar disorder from the ECA survey (

1) would yield per-patient annual treatment costs of approximately $5,100—$4,000 for inpatient care and $1,100 for outpatient care.

We arrived at a somewhat lower estimate of total specialty treatment costs—$1,575 over six months including unpaid charges—and a much lower estimate of inpatient costs. Our estimate of the proportion of treated patients using any inpatient services over six months—8 percent—is also considerably lower than similar estimates from the ECA survey of approximately 15 percent (

3). The difference between our estimates of inpatient utilization and those from earlier sources may reflect the underrepresentation of severely ill patients in the insured population or recent decreases in use of inpatient care. Our estimate of overall treatment costs is similar to the average yearly cost of approximately $2,600 from a Department of Veterans Affairs sample reported by Bauer and associates (

9).

The sample of patients with bipolar disorder in this study was limited to those recognized and treated and was somewhat biased toward those treated by mental health specialty providers. We excluded patients with isolated diagnoses or prescriptions from primary care providers. Our chart reviews found that fewer than 20 percent of those patients had bipolar disorder and that those with diagnoses of bipolar disorder were less symptomatically ill than the patients who met our criteria for inclusion in the study sample. Inclusion of any patients with bipolar disorder in these subgroups could increase the sample of treated patients by 20 to 25 percent, and these additional patients would have used fewer specialty and inpatient services. Our method of identifying patients treated for bipolar disorder yielded a treated prevalence rate (

7) lower than that in community surveys (

1) but higher than that in other health plan samples (

10,

11).

Our findings may not necessarily generalize beyond this sample of patients with stable insurance coverage selected primarily through outpatient diagnoses or prescriptions. Inpatient services would probably account for a larger proportion of utilization in an uninsured sample or one selected from inpatient or emergency room settings. Utilization and cost patterns in this sample also reflect the characteristics of this particular health plan, which included self-referral to specialty mental health services, moderate cost sharing for outpatient mental health services, prescription drug coverage, and limitations on long-stay psychiatric hospitalization.

Our main classification of mental health and substance abuse treatment did not include general medical visits with mental health content. Our analyses of diagnoses associated with general medical visits estimated that 25 to 35 percent of primary care and emergency room visits in the bipolar and depression groups were partly or wholly dedicated to treatment of mood disorder. Reclassifying these visits as mental health treatment would have greatest effect in the depression group—doubling our estimate of resources devoted to mental health treatment and reducing differences between the depression and bipolar disorder groups in expenditures for outpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment.

Patterns of utilization among patients treated for bipolar disorder differ markedly from those of patients treated for depression. Specialty mental health and substance abuse services accounted for approximately 45 percent of total expenditures in the bipolar group, compared with 10 percent in the depression group. Within the specialty mental health and substance abuse category, inpatient care was approximately one-third of the total in the bipolar disorder group, compared with 10 percent among those treated for depression. The bipolar disorder group had lower general medical expenditures than the depression group, but this difference was not statistically significant. In a population-based sample such as ours, most depression treatment will occur in primary care. Patients treated by mental health specialists—that is, patients with more severe or chronic illness—would certainly show different patterns of resource use.

The economic burden of caring for bipolar disorder concentrates in a small portion of the treated population. One-fifth of patients with the most severe or complex illness accounted for all inpatient utilization and the majority of outpatient care. Five percent of patients accounted for the vast majority of inpatient resources. If more organized outpatient treatment programs could reduce hospitalization in this small group of patients, such programs could substantially reduce both overall treatment costs and the financial burden on patients and families.

Our data demonstrate that the financial burden of more restrictive coverage for mental health care involving, for example, annual limits and higher coinsurance or deductibles, falls on a small proportion of the population with the most severe illness. We do not know, however, what proportion of these additional charges was paid by patients and what proportion was absorbed by inpatient facilities as bad debt. We must also recognize that our data may understate the impact of out-of-pocket costs; some patients may avoid clinically indicated inpatient care because of high copayments or coinsurance.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that elimination of discriminatory coverage for mental health inpatient care would have only modest effects on overall costs to the health insurer. As seen in

Table 2, parity coverage of inpatient care would lead to an increase of approximately 15 percent in mental health and substance abuse treatment costs and an increase of 6 percent in overall health care costs. If these additional costs were spread over the entire population, rather than the 1.5 percent treated for bipolar disorder, the increases in overall costs for mental health and substance abuse care would be less than 1 percent.

These data do not support any firm conclusions about the appropriateness or efficiency of care for patients with bipolar disorder. Evaluating the cost-effectiveness of care requires an integrated view of quality of care and patient outcomes as well as cost. We do find, however, that 5 percent of patients treated for bipolar disorder accounted for approximately 40 percent of all specialty mental health and substance abuse costs, and more than 90 percent of costs for inpatient mental health and substance abuse treatment. Additional research is needed to determine if more organized outpatient treatment could prevent relapse and reduce the probability of expensive inpatient stays.