In 1857 the

American Journal of Insanity, which later became the

American Journal of Psychiatry, published an article by Edward Jarvis, M.D., of Dorchester, Massachusetts (

1), that suggests the plight of criminal offenders with mental illness and their need for care are not recent phenomena. Dr. Jarvis wrote, "The insane criminal has nowhere any home: no age or nation has provided a place for him. He is everywhere unwelcome and objectionable. The prisons thrust him out; the hospitals are unwilling to receive him; the law will not let him stay at his house, and the public will not permit him to go abroad. And yet humanity and justice, the sense of common danger, and a tender regard for a deeply degraded brother-man, all agree that something should be done for him—that some plan must be devised different from, and better than any that has yet been tried, by which he may be properly cared for, by which his malady may be healed, and his criminal propensity overcome."

Today society continues to face the challenge of providing proper care for offenders with mental disorders within the growing population of persons under the jurisdiction of the correctional system in the United States. This paper briefly reviews recent research on the prevalence of mental illness among criminal offenders and the effects of clinical interventions with this population. It describes a small model program for offenders with mental illness that involves collaboration between clinical staff of a community mental health center and a probation officer from the U.S. correctional system.

Methods

In response to a wide disparity in ease of access to neighborhood clinics, the second author, a probation officer with the United States Probation Office in Baltimore City, determined that an alternative approach was needed if his clients were to receive adequate mental health and addiction services. In April 1996, he contracted with a specific provider of care for services to his caseload of offenders on federal parole, probation, and supervised release who were mentally ill.

The clinical model in use in this program—a fairly typical community mental health model—is described in detail elsewhere (

30). Briefly, each patient, or offender, is assigned to a psychiatrist, the first author, and one of the program's two master's-level therapists is assigned to work with the probation officer. Care within the community mental health center is coordinated by the clinicians and may include medical treatment, intensive case management, addictions treatment, urine toxicology screening, and psychosocial or residential rehabilitation services. Services are provided elsewhere for patients who may need a period of more intensive care, such as intensive outpatient treatment, partial hospitalization, or inpatient treatment. These services are brokered by the community mental health center's clinical team.

All patients who are referred to the community mental health center are informed at the beginning of the evaluation process and throughout treatment of the close connection and frequent contact between the clinicians and the probation officer. The probation officer is routinely kept informed of patients' clinical progress. If a patient misses an appointment or the treatment team notices other forms of treatment noncompliance, the probation officer may act in an outreach function for the clinical program. Decisions about changes in patients' housing, major alterations of the treatment plan, or discontinuation of services always involve the probation officer's input.

Results

We present descriptive data from the first group of offenders enrolled in this clinical model, with emphasis on length of tenure in the treatment program. As of May 1998 a total of 16 patients had been referred for treatment by the probation officer.

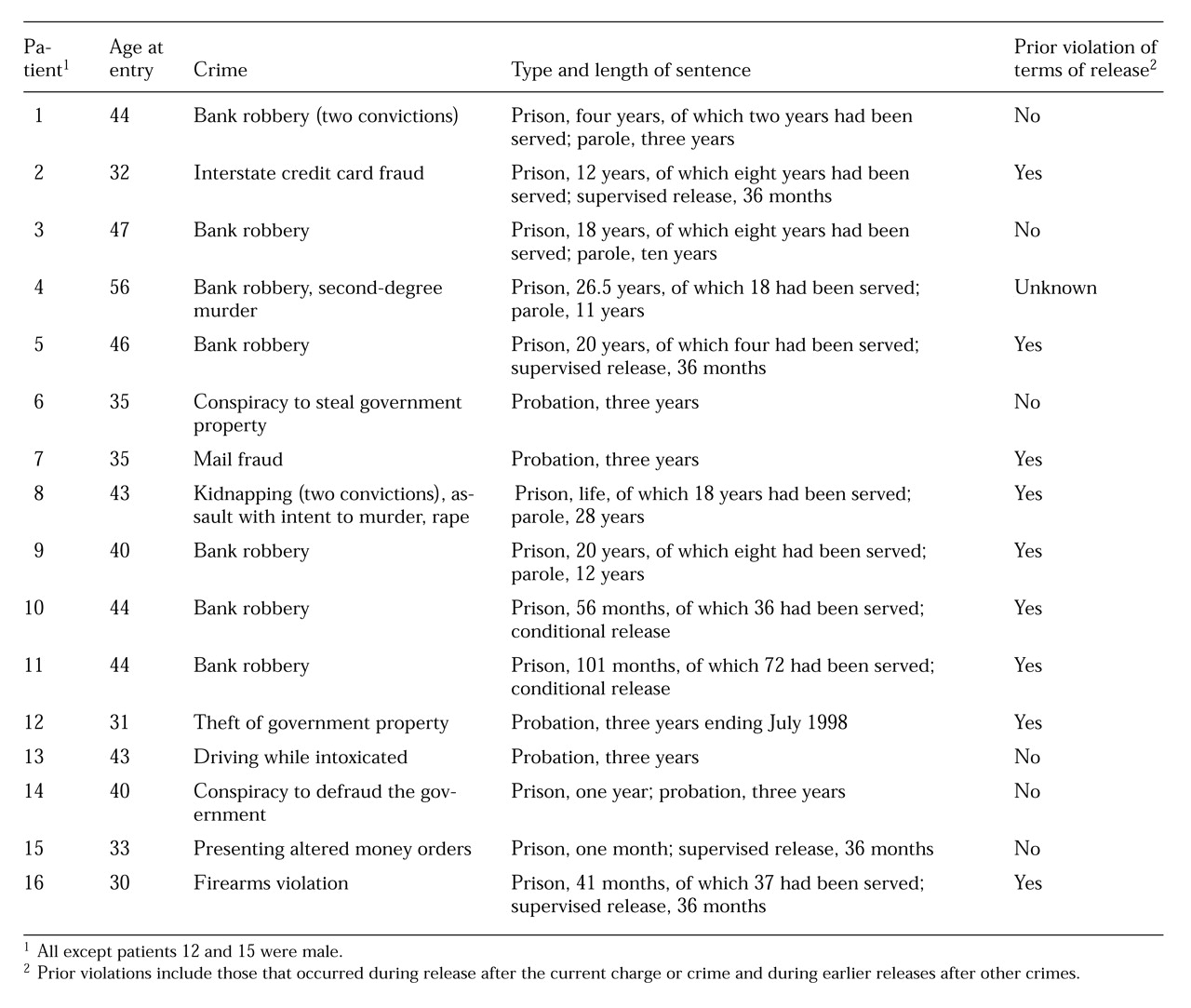

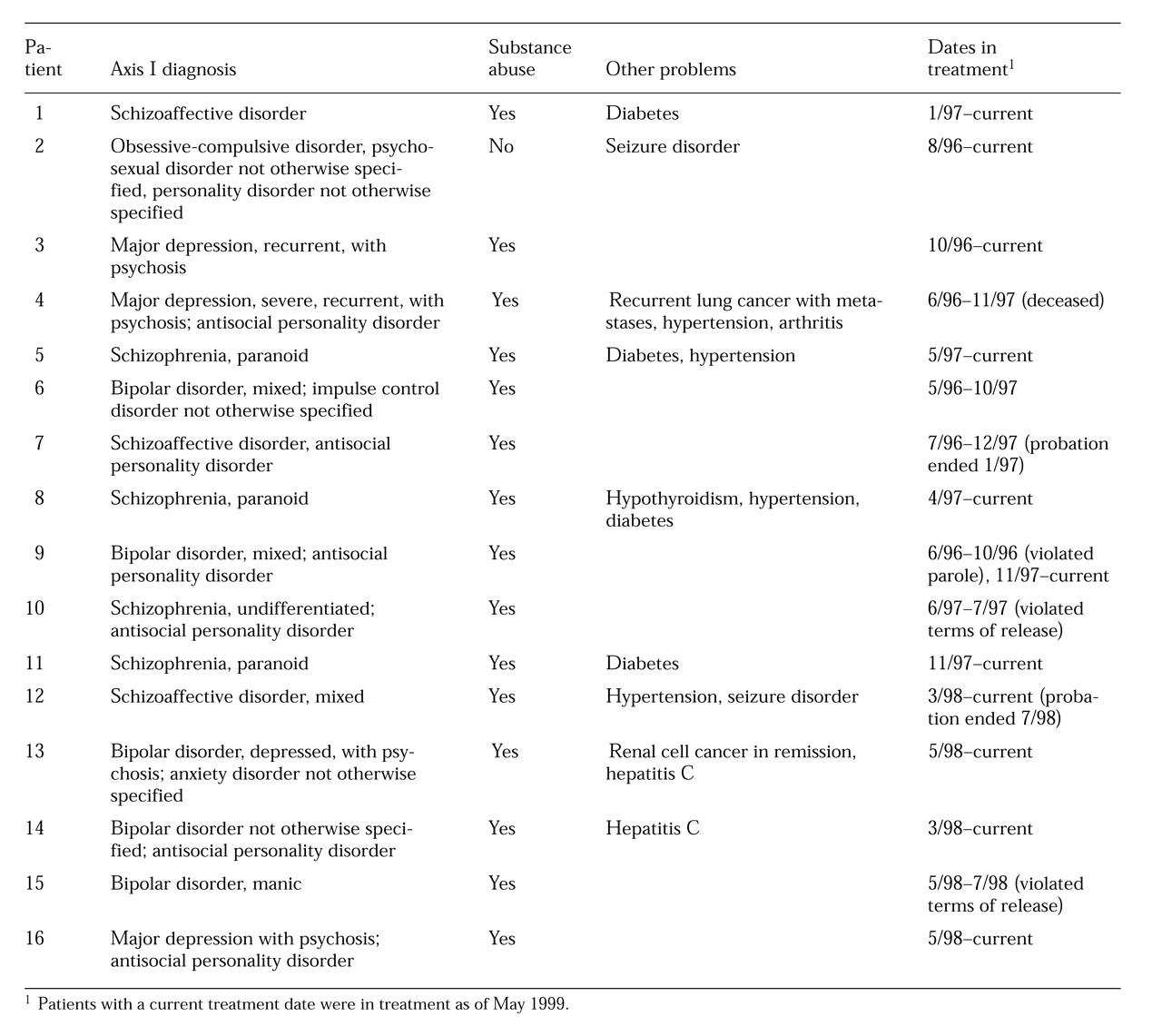

Table 1 and

Table 2 show the legal and clinical characteristics of the patients. Fourteen were male, and 14 were African American, reflecting the offender population of Baltimore City. They ranged in age from 30 to 56 years. All had been accepted into treatment, although one patient kept only two appointments and another kept just one. Both of these patients violated the terms of their community supervision by noncompliance with stipulations for mental health treatment. One other patient violated the terms of his parole because of noncompliance with treatment; however, the noncompliance occurred after he was hospitalized in an attempt to keep him in active treatment. After he was released and referred back to the treatment team, he did well in treatment.

Thus of the 16 referrals, three patients received criminal sanctions due to noncompliance with treatment. Only one of these patients had been successfully engaged in treatment before violating the terms of his release. As noted in

Table 1, nine of the 16 patients in this cohort had a history of parole or probation violations.

The terms of supervision for two patients had expired or were terminated as of May 1999. One completed his term eight months after beginning treatment under the contracted arrangement. He remained a voluntary patient with the treatment team for 11 months after his supervision was terminated and then failed to keep appointments, and his case was closed. The probation of another patient was terminated within four months after she started treatment; she remained in treatment in May 1999, ten months after her probation ended.

Discussion and conclusions

This paper is the first we have found that reports data from a collaborative clinical-probation treatment model for offenders with mental illness. Because the program was designed as a clinical intervention, without prospective research questions, the conclusions that can be drawn from the clinical data are limited. Nonetheless, the data are intriguing and suggest the need for further study.

In the cohort of patients described, the rate of violation of probation, parole, or supervision was 19 percent. This same group of offenders had a violation rate of 56 percent before their current release. Several of the patients had violated the terms of their release numerous times in the past, but the data presented here suggest that the program's intervention may have had an impact on the level of compliance with conditions of release.

We suggest that this result can be attributed in part to the close working relationship between the clinical team and the probation officer. The ongoing regular contact has allowed the clinicians who work with these clients to develop an understanding of the community supervision system and of its responsibilities for public safety. In turn, the social work background of the probation officer has helped him understand his clients' mental health needs and the operation of the mental health treatment system. In situations where many probation officers might rapidly seek revocation of supervision, the existence of this contract and the cooperation between the contracting agencies allows all treatment options, including voluntary and involuntary hospitalization, to be exhausted before sanctions are deemed necessary.

An important facet of this program is its capacity to address co-occurring mental and addictive disorders in an integrated fashion. Most of the patients referred to the mental health center have already been involved in the center's substance abuse program. Often their mental health needs were initially met by consulting psychiatrists working in the addictions treatment program. However, the needs of many patients for therapy or case management outstripped the capacity of the addiction treatment staff, and many patients were referred to the mental health program. In all of these cases, the patient continued to be involved in the substance abuse program, which includes urine toxicology screens and drug counseling. The two programs are located in the same building, which facilitates their collaboration to successfully treat dual diagnoses and to respond to the public safety requirements of the probation officer.

The contractual arrangement has enhanced the probation officer's access to a wide range of mental health services for his clients. Before the development of the contract, sources of mental health care were chosen based on the catchment area in which the client lived. The probation officer repeatedly faced the need to educate new clinicians about the corrections system, and development of a firm working alliance was unlikely because only one or two clients were being treated in any particular clinic.

The contract has made the mental health center's clinicians accountable to the probation officer both clinically and fiscally. In return, the probation officer can assure the clinicians of his ongoing support. In some cases, the probation officer has served as an outreach contact when patients begin to decompensate or to miss appointments. This added outreach has allowed the mental health center clinicians to provide fairly intensive treatment, without having to refer these offenders to more costly treatment programs. The collaboration has hinged on the consensus that information sharing would be used in the interest of patients' treatment needs and that legal sanctions for patients' violation of the terms of release would be a last resort.

A major problem for widespread application of the treatment model is the lack of coordination between the prison system and the community correctional system. For example, because the federal prisons constitute a nationwide system, an offender with mental illness may be housed in a prison located hundreds of miles from his or her eventual community placement. Prison staff are unlikely to be aware of the resources in the city where the inmate is to be released and must rely on the local probation officer's knowledge of community resources for essential prerelease case management. However, not all probation officers are aware of community resources that would be appropriate for offenders with mental illness.

As noted, the program described here was not designed with a priori research questions in mind. Thus a major drawback of this descriptive study is the absence of a control group, making it impossible to form conclusions about the effectiveness of the clinical model in retaining its clients or in reducing recidivism. Using the cohort as its own control might lead to the conclusion that the treatment model is effective, at least in broad terms of violations of parole or probation. In our opinion, this conclusion is not valid, given the large number of uncontrolled variables, including length of time in the community before violation of release terms and reason for the violation.

Although we have the impression that the model has resulted in reduced burden of illness to the offenders enrolled in the program and to a lower rate of criminal activity, these findings may be the result of the cohort's older age range, from 30 to 56 years. Older age has been associated with remission of antisocial symptoms (

31).

Despite these drawbacks of the study, this collaborative model appears to be applicable to many settings in which the mental health and community correctional systems interact. Research should be conducted to test the cost-effectiveness and clinical and criminal justice outcomes of this approach. Although our model involves the federal correctional system, it could also be used in other correctional systems. The working relationship of clinical and community correctional personnel meets the mental health needs of the patients while ensuring that the safety interests of the courts and the public are protected, in a cost-effective, efficacious, and humane manner.