The National Adult Literacy Survey, sponsored by the Department of Education in 1992, found that 40 to 44 million adults in the U.S. lack the necessary reading skills to understand basic written materials (

1). For a variety of reasons, low literacy represents a profound obstacle to the effective negotiation of the current health care system in the U.S. (

2,

3). Poor reading skills hinder an individual's ability to understand medication labels, comprehend appointment slips, and follow-up on health care referrals. Recent research has shown that individuals with low or limited literacy suffer from poorer health and have higher expenses for health care, more outpatient clinic visits, and a greater likelihood of hospitalization than those with better-developed reading skills (

4,

5).

However, few studies have specifically examined the prevalence of low literacy in a psychiatric population. Individuals who suffer from both a mental illness and limited literacy are likely to be additionally disadvantaged in effectively using mental health care services. The purpose of the study reported here was to identify the extent of low literacy in a psychiatric population that received mental health services at a shelter-based clinic for the indigent.

Methods

Study participants were 45 consecutive patients who sought mental health care over a four-month period (January through April) in 1997 at the Helping Hands Clinic for the Homeless in Gainesville, Florida. In general, the vast majority of clinic patients are indigent individuals who are either homeless or are at increased risk of becoming homeless.

The nonappointment, walk-in clinic operates one evening a week in a shelter for the homeless in downtown Gainesville. It was established in 1989 to meet the primary and mental health care needs of indigent and low-income individuals who are unable to gain access to other systems of medical care. The mental health care is provided by volunteer psychiatrists drawn from the local community.

After obtaining informed consent from each study participant, the first author collected demographic and clinical data, including age, gender, ethnicity, housing status, and DSM-IV diagnosis, and information on the last school grade level successfully completed. Surprisingly, the refusal rate in the study was zero.

After these data were collected, the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) screening test (

6) was administered to the patients by the first author, who had received formal training in using the instrument. The REALM is a word recognition and pronunciation test that uses medical terms of varying levels of difficulty. It takes approximately three minutes to administer and is especially useful in identifying low literacy in people who need to read medical materials as part of their care (

4). Previous research has shown the REALM to be a reliable and valid screening tool for identifying individuals who have difficulty reading common medical and lay terms that are routinely used in primary care patient education materials (

6).

Results

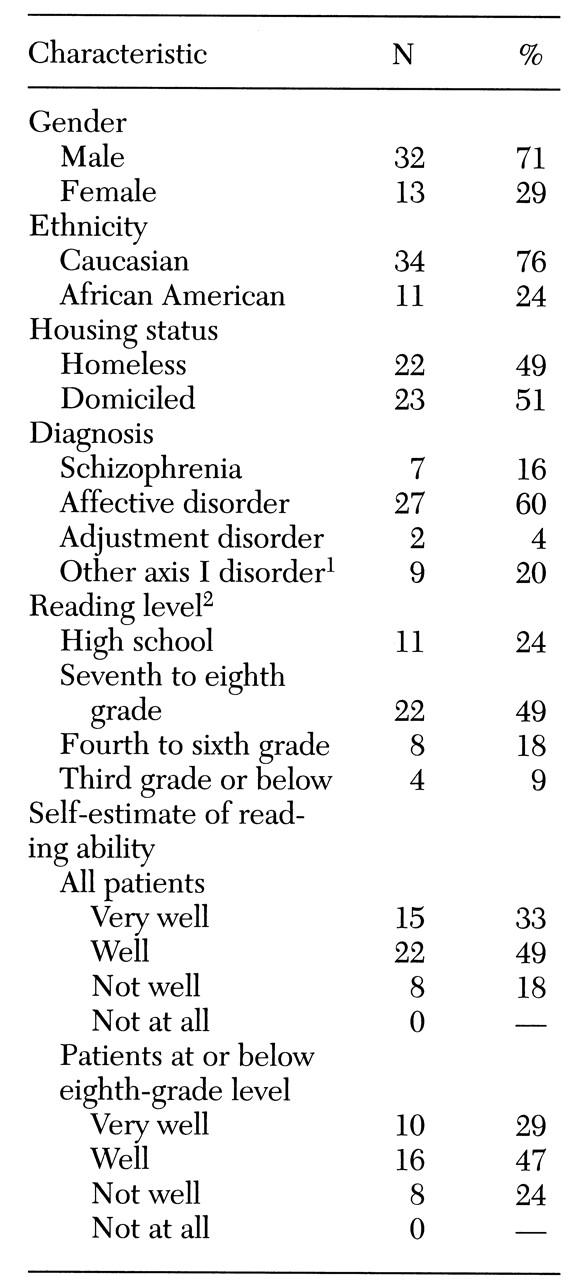

Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics of the 45 study participants. The group included more than twice as many men as women and three times as many Caucasians as African Americans. Ages of participants ranged from 19 to 67 years, with a mean age of 32 years. About half (49 percent) were homeless.

REALM scores for the 45 patients revealed an overall mean reading level in the seventh- to eighth-grade range. In the sample distribution of reading scores, 11 patients (24 percent) read at the high-school level. However, 22 patients (49 percent) read at the seventh- to eighth-grade level, eight (18 percent) at the fourth- to sixth-grade level, and four (9 percent) at the third-grade level or below. In contrast, when asked to estimate how well they read before testing, 15 patients (33 percent) said "very well," 22 patients (49 percent) said "well," and only eight patients (18 percent) reported they read "not well."

A total of 34 patients (76 percent) read at the seventh- to eighth-grade level or below. When self-estimates of reading ability for these patients were examined, a distribution very similar to that for the entire group was found. In this low-literacy group, ten patients (29 percent) estimated they read "very well," 16 patients (47 percent) said they read "well," and only eight patients (24 percent) reported they read "not well."

Discussion and conclusions

Although the study findings are limited by the small size of the sample, more than 75 percent of patients presenting for mental health care read at or below the seventh- to eighth-grade level. However, because of the nature of the REALM, this finding is based entirely on word recognition by the study participants. Actual reading comprehension skills are likely to be even lower than shown by our data.

Interestingly, 76 percent of the sample reported reading very well or well. Moreover, participants had completed a mean of 11 years of formal education. These findings alone underscore a number of formidable challenges for persons who suffer from low literacy and for the clinicians who provide their care.

First, mental health care providers must become increasingly aware of the prevalence and management of limited literacy in their respective practice settings. As evidenced by our data, self-estimates of reading ability are likely to be unreliable. Individuals with low literacy may not recognize they have a problem and often will attempt to hide it if they do (

2,

7). Moreover, the assumption that a patient's reading level accurately corresponds to the last grade successfully completed is frequently erroneous. Hence routine screening of reading ability may be necessary to identify those who will require special assistance in effectively utilizing mental health care services.

Second, clinicians practicing in settings that have a high prevalence of low literacy should remain mindful that most patients will not understand the majority of educational hand-outs and consent forms because these materials are written at the tenth-grade level or higher (

5,

8). Clinicians might consider using materials prepared at the lowest possible level of reading difficulty (such as fifth-grade level) to communicate important information such as medication side effects, emergency telephone numbers, or referrals to other health care providers or systems of care (

5,

9). Above all else, providers should remember the critical importance of effective verbal and other nonwritten means of communication to ensure that individuals with limited literacy skills fully understand matters relevant to their mental health care.

Although this study has important limitations, including the small sample size and use of a screening tool that measures word identification rather than comprehension, the findings nonetheless highlight the importance of identifying individuals in the clinical setting who show evidence of low literacy. Whether our results can be generalized to domiciled individuals with serious mental illness is open to speculation but clearly should be a focus for future research. Nonetheless, access to and utilization of effective and compassionate mental health services may be contingent on providers' recognizing the presence of this clinically significant, but potentially surmountable, obstacle to care.