Regarding treatment, a body of literature has evolved steadily over the past two decades that addresses the effectiveness of treatment programs for sex offenders, but it remains specialized and unfamiliar to many general psychiatrists (

4,

5,

6,

7). It is commonly assumed, and even argued in support of public policy, that disorders involving aggressive sexual behaviors are unlike other mental illnesses because they are untreatable. The purpose of this paper is to examine this assumption more closely by reviewing the research on the effectiveness of treatment for sex offenders, focusing primarily on adult males.

Background

Recent research has suggested that more than half of all women and one-fifth of all men in the United States will be sexually assaulted at some point. One study estimated that by the time rapists enter treatment, they had assaulted an average of seven victims and that nonincestuous pedophiles who molest boys had committed an average of 282 offenses against 150 victims (

8). The impact of these offenses on their victims can be devastating. The number of sex offenders in state prisons has increased by more than two-thirds in the last decade, leading to increasing burdens on public budgets (

9). The number of treatment programs has grown, although some programs have closed due to limited funds (

9).

Identified on the basis of sexual behavior sufficiently aberrant and aggressive to bring the perpetrator to the attention of law enforcement officials, sex offenders as a group include a variety of types of individuals. Although it has been suggested that the vast majority of rapists have no mental disorder other than antisocial personality disorder (

3), many offenders meet diagnostic criteria for paraphilias, especially pedophilia, and may also suffer from comorbid anxiety, depressive, or psychotic disorders.

Some treatment programs have attempted to assess the outcomes of their interventions. However, little is definitively known about the efficacy of many of the treatments currently in use, and research necessary to produce such knowledge must confront particularly difficult problems. Before discussing the nature of sex offender treatment and its outcome, we will review the major difficulties this type of research must face.

Somatic therapies

This section reviews research on somatic therapies for adult male sex offenders. Several surgical and medical treatments not frequently used today are described briefly. Next, we provide a more extensive discussion of antiandrogen treatments for sex offenders, including two tables summarizing the relevant studies. Antiandrogen treatment is the most successful direction for biological treatment to date. Finally, we review other hormonal and serotonergic agents, relatively new medications that may be promising in the treatment of sex offenders.

Surgical treatments

Surgical treatments for sex offenders are of two general types: neurosurgery and castration. The neurosurgical procedure, stereotaxic hypothalamotomy, involves removal of parts of the hypothalamus to disrupt production of male hormones and decrease sexual arousal and impulsive behaviors. However, the neuroendocrine mechanisms involved are not well understood, and the procedure has shown a significant failure rate and adverse sequelae.

For primarily ethical reasons, surgical castration has not been widely advocated as a treatment for sex offenders, and in some countries such treatment is illegal. Castration has been shown to be highly effective in European literature. For example, Cornu (

40) reported that among a group of sex offenders followed for periods of five to 30 years, those who had accepted the option of castration had recidivism rates of 5.8 percent compared with 52 percent for those who refused castration. Recidivism rates have been reported to decrease over time following the procedure, which may be related to the rate of decline of testosterone levels following the procedure (

41). Such a finding, if substantiated, might contribute an empirical basis for determining clinically indicated lengths of hospitalization or institutional confinement following surgery.

Favorable reports on castration have been countered by reviews in which it has been disparaged on ethical grounds and scientifically discredited as not 100 percent effective. With the advent of sexual predator laws, castration as a treatment option is now subject to discussion that includes media attention to individual cases as well as focused state legislation specifying the conditions under which orchiectomy may be performed. Recent legislation permitting voluntary orchiectomy in Texas was coupled with a requirement for follow-up research on recidivism (

42).

Medical treatments

Before the more widespread use of antiandrogens in the treatment of sex offenders, clinicians attempted treatment with oral and implantable estrogens (

43) and with an estrogen analogue, diethylstilbesterol (

44). In general, research findings agree that the potential for adverse effects limits the utility of estrogen treatment for sex offenders (

45).

A number of early studies reported on the treatment of sex offenders with neuroleptics (

46,

47,

48). However, these agents were found to be of limited benefit, which did not outweigh the risk of tardive dyskinesia. Antipsychotic agents may benefit sex offenders with comorbid psychotic disorders, especially patients who are receiving hormonal therapy, which may exacerbate psychosis (

45). The advent of newer, atypical antipsychotic medications may warrant a reassessment of therapeutic effects and side-effect risks associated with these medications.

Antiandrogen medications

Among the most important biological advancements is the use of antiandrogen medications. The two most widely used forms are medroxyprogesterone acetate (MPA), available in the United States, and cyproterone acetate (CPA), available in Canada and Europe. Both are synthetic progesterones that reduce the serum level of circulating testosterone, with concomitant reductions in sex offenders of self-reported deviant sexual fantasies and behaviors (

49,

50). Reduction of testosterone has been shown to reduce libido, erections, ejaculations, and spermatogenesis (

51). A library search covering the past 20 years found more than 30 papers reporting the effectiveness of antiandrogens in reducing testosterone levels for sex offenders, along with decreased self-reported deviant sexual drive, fantasy, and behavior.

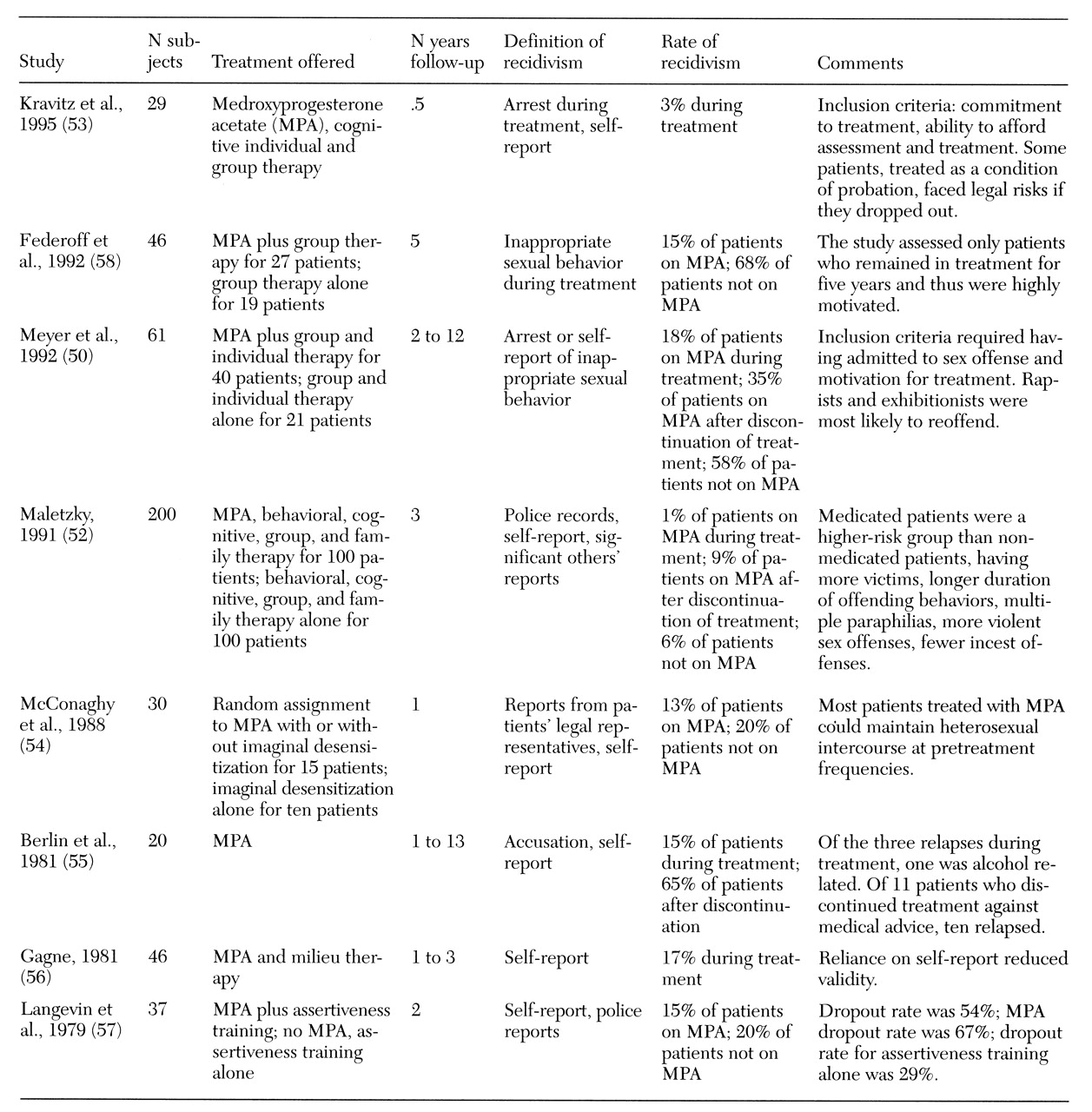

Table 1 summarizes recidivism rates for eight outcome studies of sex offenders treated with antiandrogens (

50,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58). The studies report a spectrum of differences between patients treated with antiandrogens and those not treated, with recidivism rates as low as 1 percent for treated patients and as high as 68 percent for untreated patients. Recidivism rates for patients initially treated with antiandrogens who discontinued treatment fell between the rates for completers and nontreated patients.

Although the number of studies like these is still small, antiandrogen medication appears promising in the treatment of sex offenders, especially because the effectiveness of antiandrogens in reducing sexual behavior generally is well documented. The outcome studies suggest that antiandrogens, while not effective for all patients (

59), appear to reduce sex offender recidivism in many cases.

Research findings have suggested that sex offenders treated with MPA may experience suppression of deviant fantasies and behaviors earlier in treatment (one to two weeks) than suppression of nondeviant fantasies and behaviors (two to ten) (

53). If these results are confirmed, they suggest that careful dose titration may allow patients to maintain appropriate sexual behavior while eliminating deviant behavior. Low-dose oral administration of MPA has been attempted, but rigorous research is needed (

60).

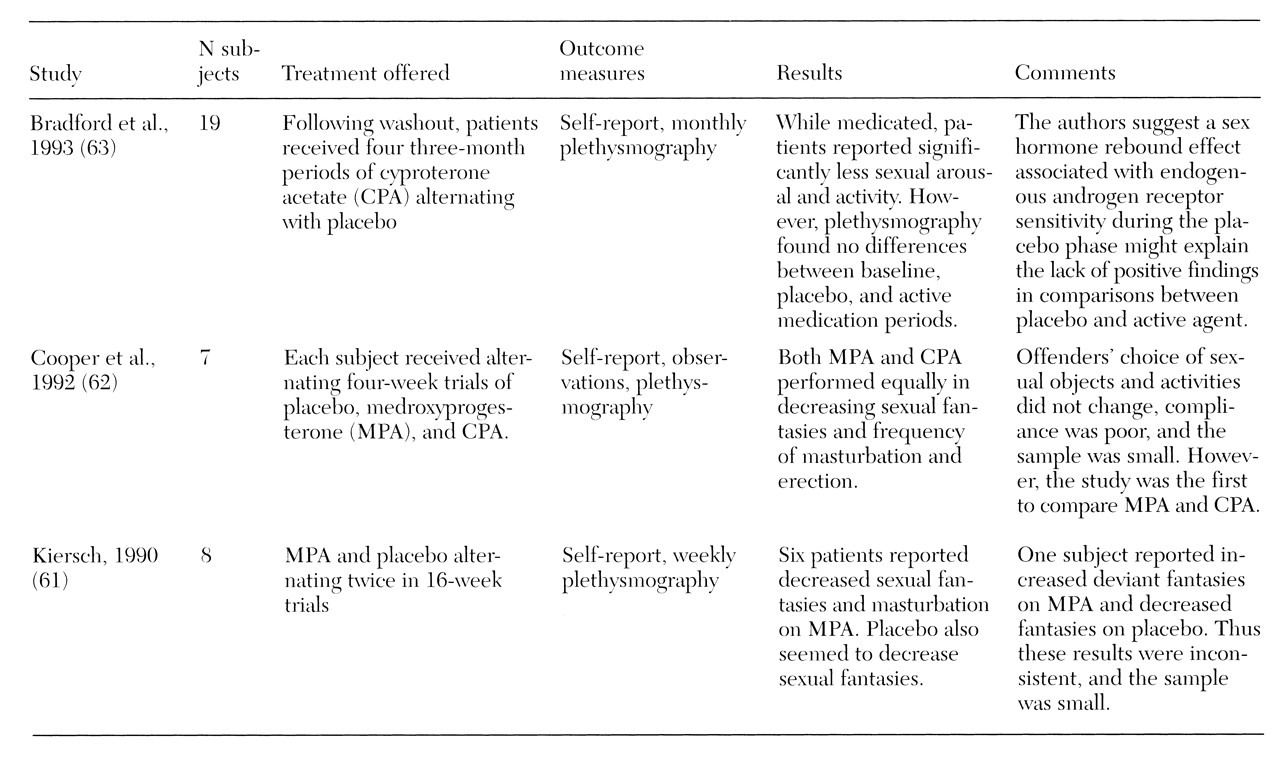

Although placebo-controlled studies may be difficult to achieve with antiandrogens, some have been attempted.

Table 2 summarizes the results of three placebo-controlled double-blind crossover studies (

61,

62,

63), which show mixed results. All three studies alternated antiandrogens with placebo, using each subject as his own control. These studies all showed that during the active phase of medication, patients reported decreases in some aspects of their sexual behavior, including deviant sexual thoughts, fantasies, and frequency of masturbation. However, in all three studies, plethysmography did not consistently support patients' self-report. Indeed some patients showed increased deviant arousal while on antiandrogens and decreased deviant arousal during the placebo phase. Bradford and Pawlak (

63) suggested that an endogenous sex hormone rebound effect associated with androgen receptor sensitivity during the placebo phase might explain the lack of positive findings in some comparisons between placebo and active agent.

Previously, direct comparisons of MPA and CPA were not done because the two drugs were not available in the same country. In 1992 Cooper and associates (

62) provided the first direct comparison of the two agents. The results suggested that MPA and CPA performed equally in decreasing sexual thoughts and fantasies, frequency of masturbation, and erection.

Thus outcome studies of antiandrogen treatment appear promising. However, certain cautions apply:

• The drugs must be used cautiously in treating patients with migraine, asthma, or cardiac dysfunction and are contraindicated for patients with diseases affecting testosterone production (

53).

• They may produce side effects, including weight gain, depression, hyperglycemia, hot and cold flashes, headaches, muscle cramps, phlebitis, hypertension, gastrointestinal complaints, gallstones, penile and testicular pain, and diabetes mellitus (

50,

53). CPA can cause feminization (

45).

• As with many other forms of treatment, antiandrogen medication is associated with high dropout rates (

50,

57,

58).

• Antiandrogen treatment requires a level of medical management that can be costly, reducing its availability to broad populations.

• The long-term consequences of use of these drugs are not known; some clinicians recommend using them for only short time periods (

52).

Newer hormonal therapiesand serotonergic agents

Several case reports have suggested that analogues of gonadotropin-releasing hormone may be useful either alone or in combination with antiandrogens (

64,

65,

66). These agents inhibit the secretion of luteinizing hormone with a resulting decrease in plasma testosterone levels and libido (

45). Dickey (

59) described the use of a long-acting depot-injectable luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist in treatment of a patient with multiple paraphilias who had shown a poor response to both MPA and CPA. The patient was reported to have complete cessation of deviant sexual behavior after one month of treatment and decreased frequency of masturbation. The use of LHRH agonists apparently avoids unwanted side effects seen with MPA and CPA (

59).

In a recent open study, Rosler and Witztum (

65) treated 30 men with severe longstanding paraphilias with monthly injections of triptorelin, a long-acting agonist analogue of gonadotropin-releasing hormone, for eight to 42 months. The results indicated that all men showed a decrease in deviant sexual fantasies, desires, and abnormal sexual behavior. These effects persisted in all of the 24 men who continued in treatment for one year. Treatment was associated with suppression of serum testosterone. Further study is needed before conclusions can be drawn about the efficacy and safety of these agents. However, gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues and related agents may provide alternative hormonal therapy in cases where antiandrogens fail (

59).

A number of small studies and case reports (

67,

68,

69,

70,

71,

72) have found treatment with antidepressants helpful for patients with paraphilias. These studies have included patients for whom tricyclics or lithium was used (

70). However, most of the more recently reported successes have been with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) (

67,

68,

69). Many patients in these series were reported to have concurrent mood or anxiety disorders. The anxiolytic buspirone, a 5-HT1A partial agonist, has also been reported effective in reducing paraphilic fantasies (

67,

68,

73,

74).

These reports have noted that the serotonergic agents, including buspirone, appear to have specifically antiobsessional effects in patients with paraphilias and related sexual obsessions; such clinical observations are consistent with the demonstrated efficacy of SSRIs for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Although these findings are mostly anecdotal, further research could confirm a role for SSRIs, other antidepressants, or other serotonergic agents in the treatment of paraphilias. Clearly, in the presence of comorbid anxiety or depressive disorders, a trial of these agents may be indicated.

Overview of treatment efficacy

Several investigators have compiled the data from treatment outcome studies, despite variation in types of treatment, patients treated, and research design. Furby and colleagues (

95) amassed data from numerous studies of sex offenders that included at least ten subjects and used criminal justice records for outcome measures. The review covered almost 7,000 men. The authors concluded that their review failed to provide any convincing evidence that treatment is effective in reducing recidivism of sexual offenses. They further stated that their data did not permit evaluation of the relative effectiveness of treatment for different types of offenders. In fact, the authors reported difficulty discerning any patterns relating treatment to recidivism, including the expected pattern that longer follow-up periods would produce higher recidivism rates.

When these authors compared treated patients to untreated patients, they found that untreated patients had recidivism rates below 12 percent, while treated sex offenders in two-thirds of the studies had recidivism rates above 12 percent. The authors suggested that treatment outcome studies may monitor subjects more closely during the follow-up period, leading to a greater likelihood of detection of subsequent arrests. Further, they suggested that pre-existing differences between treated and untreated sex offenders—apart from whether they received treatment—may mean that any conclusions to be drawn must remain tentative (

95).

Marshall and Pithers (

6) criticized the Furby review, arguing that its findings are no longer applicable since they are based on studies mostly published before 1978, before the use of the cognitive-behavioral techniques so prevalent today. Indeed most of the programs reviewed by Furby and colleagues no longer exist. Further, Marshall and Pithers argued that the samples reviewed by Furby and colleagues overlap in at least one-third of the studies reviewed, which biases the results against positive findings. Thus Marshall and Pithers concluded that the findings of the Furby review are inappropriately pessimistic.

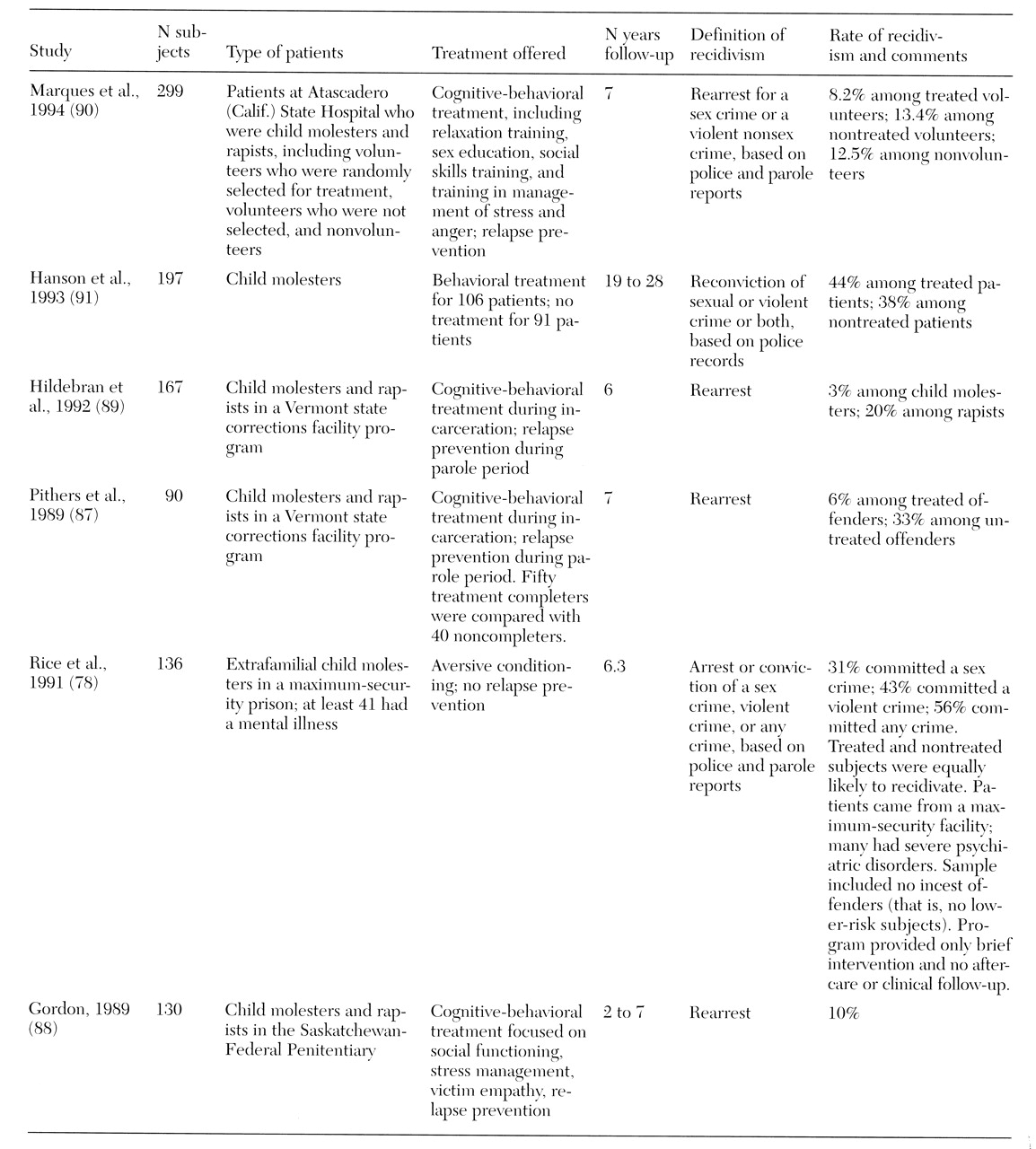

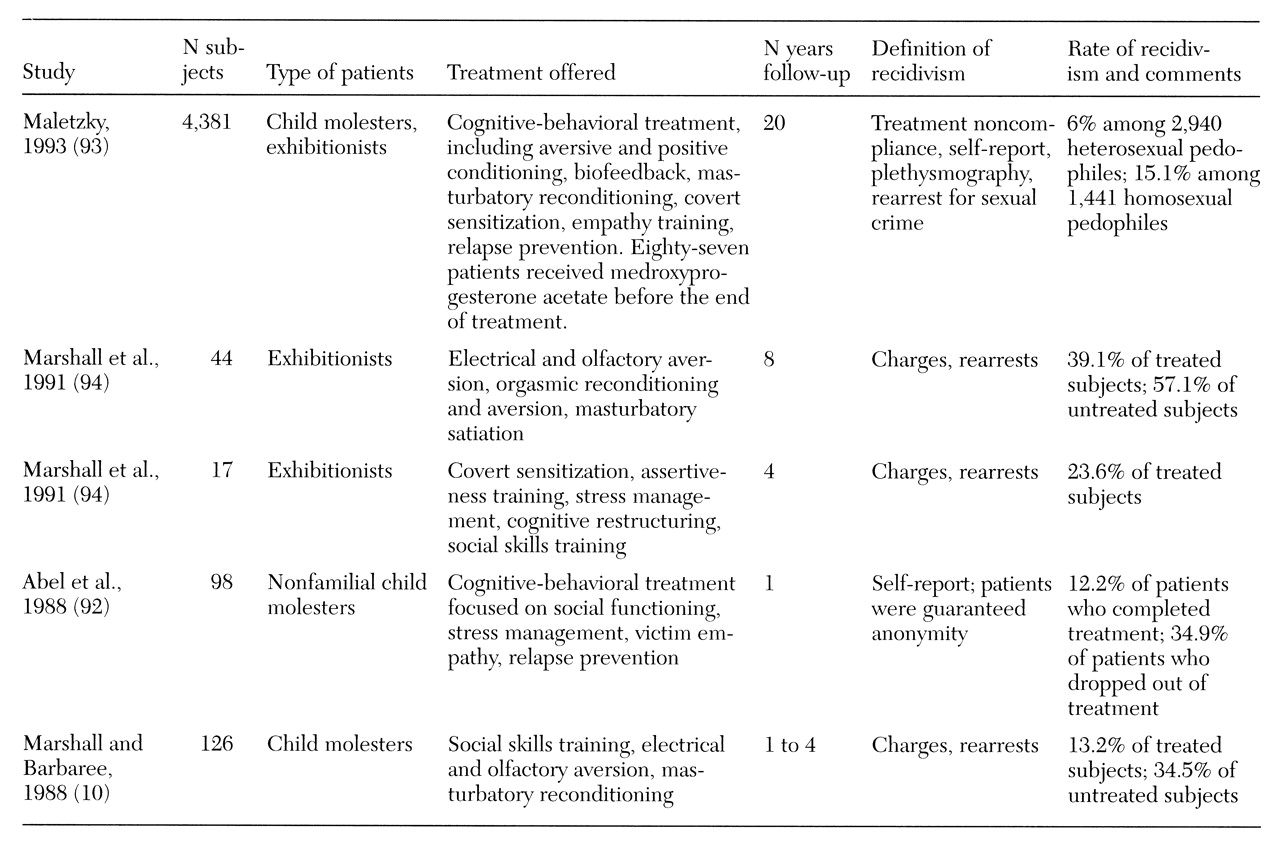

The best methodology for integrating the sex offender treatment data is meta-analysis. Until recently, this procedure was precluded by the inadequate descriptions in many studies of sampling techniques or outcome measures, differences in sample sizes, types of subjects assessed, types of treatment, and length of follow-up. However, a meta-analysis by Hall (

96)—although limited to only 12 studies—provided an overall estimate of the results of treatment for sex offenders. This analysis included all published studies since the Furby review that compared samples of more than ten offenders who had completed a treatment program with others who had completed a comparison program or no treatment program, and that used arrest records for sexual offenses as outcome data. The mean length of treatment in the studies was 18.5 months, and the mean follow-up period was 6.9 years. Overall, the analysis found that the recidivism rate for treated offenders was 19 percent, compared with 27 percent for nontreated offenders.

The meta-analysis found that cognitive-behavioral treatment and antiandrogen treatment were comparable in their treatment effects and significantly more effective than behavioral treatment alone (

96). It is noteworthy that effect sizes—indexes of the strength of treatment outcome—were significantly greater in studies of outpatients than in studies of institutionalized patients and were greater in studies with follow-up periods of longer than five years. Effect sizes did not differ between studies that included rapists and those that did not.

Larger effect sizes were also found for patients with higher base rates of recidivism, which according to the author could reflect greater difficulty demonstrating statistically significant treatment effects in groups with low base rates of recidivism. Although the use of arrest records as recidivism criteria may underestimate recidivism, differences related to treatment should not be invalidated by this limitation because any underestimation should apply equally to treated and untreated groups.

When considering whether a sex offender is a candidate for antiandrogen treatment or cognitive-behavioral therapy, Hall (

96) pointed out that although the two forms of treatment are equally successful, the dropout rates for hormonal therapy are greater. Two-thirds of participants refused hormonal treatment (

50,

58), and 50 percent of patients who began this type of treatment discontinued it before completing the program (

57). In contrast, dropout and refusal rates for cognitive-behavioral treatment were about one-third (

92). In addition, hormonal treatments impose potential adverse medication effects and possible longer-term health risks. Obviously, cognitive-behavioral treatment avoids these problems. On the other hand, for patients who can tolerate hormonal treatment, this form of intervention may prove particularly effective. The cost-effectiveness of different treatments deserves further study.

In a large recidivism study of 408 sex offenders followed up over a mean of four years and in some cases up to ten years, Bench and colleagues (

9) used discriminant analysis to identify factors predictive of recidivism. Of most interest, the total number of felony convictions was the strongest predictor of recidivism involving sex-related offenses. Failure to complete treatment was a weaker but significant predictor as well. When a broader definition of recidivism that included nonsex offenses and probation or parole violations was used, failure to complete treatment emerged as the strongest predictor of recidivism.

A recent meta-analysis of factors predicting recidivism based on 61 follow-up studies of 23,393 sex offenders found that failure to complete treatment was associated with higher risk of recidivism of sex offenses (

97). Perhaps surprisingly, variables not associated with higher risk of recidivism of sex offenses included denial of responsibility, low motivation for treatment, length of treatment, and empathy with victims. The strongest predictor of sexual reoffense in this meta-analysis was sexual interest in children as measured by plethysmography. When the definition of recidivism was broadened to include any crime, increased risk was associated with premature termination of treatment, denial, and low motivation for treatment. Taken together, these meta-analyses suggest that failure to complete treatment is a significant predictor of criminal recidivism, including sexual reoffense, in this population.

Conclusions

Although some forms of treatment for sex offenders appear promising, little is known definitively about which treatments are most effective, or for which offenders, over what time span, or in what combinations. What emerges from the literature is a strong suggestion that a comprehensive cognitive-behavioral program should involve components that reduce deviant arousal while increasing appropriate arousal and should include cognitive restructuring, social skills training, victim empathy awareness, and relapse prevention. In addition, patients should be considered for antiandrogen medication if they are at high risk of reoffending.

In general, results from biological and cognitive-behavioral treatment programs strongly suggest that treatment decreases recidivism of sexual crimes. In evaluating whether the amelioration produced by treatment is clinically significant, Hall's meta-analysis (

96) suggested that antiandrogen and cognitive-behavioral treatment lead to a decrease in recidivism from a baseline rate of 27 percent in untreated individuals to a rate of 19 percent in patients who receive treatment. Hall summarized these findings as an outcome of eight fewer sex offenders per 100.

However, the results of his meta-analysis may be viewed in another way: from a baseline recidivism rate of 27 percent, a decrease in recidivism among treated patients to a level of 19 percent amounts to a 30 percent remission rate as a result of treatment. When viewed from this perspective, the analysis suggests an outcome of 30 fewer sex offenders per 100, and it reflects a follow-up period of nearly seven years. This outcome is not a negligible impact from the standpoint of clinical treatment.

By comparison, lithium prophylaxis of bipolar disorder—a standard treatment for a well-established psychiatric illness—was found in a recent five-year prospective study to be associated with complete remission in approximately 38 percent of patients still taking lithium (

98). Because a number of other patients dropped out of this study due to perceived lack of efficacy of lithium, this percentage may actually overestimate lithium's medical effectiveness.

Zonana (

3) has suggested, however, that the consequences of recidivism in sex offenders are so detrimental to society that a recidivism rate of zero is the only acceptable risk level. Such an assumption could lead to the conclusion that indefinite confinement is the only conceivable effective intervention with or without medical treatment. But the demonstrated reduction in recidivism that emerged in the meta-analysis of research on treatment of sex offenders is a robust finding and suggests that treatment for patients in this population improves outcome and may protect potential sexual assault victims.

Recent legislation in an increasing number of states focusing on the preventive detention of sexually violent persons has stimulated vigorous legal and policy discussion and debate (

1,

2,

3). This newer legislation may have significant impact on public mental health systems because the proceedings involve civil commitment rather than criminal prosecution and are associated with mandates for medical evaluation and treatment. Clinicians have not traditionally regarded sex offenders as falling within the target population of severely and persistently mentally ill persons considered appropriate for civil commitment.

Yet although it may be true that, in general, public mental health programs have little to offer by way of a service line tailored to this population, it is far less clear that individuals exhibiting chronic, repeated sexually aggressive behaviors do not suffer from mental illnesses. Nor is it clear that psychiatric treatment is without benefit for this patient population, despite frequent anecdotal references to the lack of effective treatments. To the contrary, research provides evidence of a robust treatment effect that has the potential to reduce sexually aggressive behavior.

Although the conclusion that sex offenders are untreatable is unwarranted, caution must be exercised in unfolding the implications of the positive treatment findings in the literature. It is worth underscoring the finding of Hall's meta-analysis (

96) that treatment of outpatients was associated with a larger treatment effect than treatment of institutionalized individuals. Further, in the discriminant analysis of Bench and colleagues (

9), failure to complete treatment was a weak predictor of sex-offense-specific recidivism in comparison with the extent of the felony conviction record.

These findings appear to suggest, unfortunately, that the more a sex offender needs confinement, the less confident we can be that treatment will have lasting benefits. Paradoxically, however, it is precisely the more dangerous subset of patients that psychiatry is being called to treat based on the new legislation. Civil commitment of sex offenders is based on the problem of perceived persistent dangerousness.

Precautions must be taken to ensure that treatment environments are appropriate for the risk level presented by these patients. Psychiatrists, other mental health professionals, and public administrators are concerned about the potential for predatory behavior by sex offenders who are mixed with the currently defined population of patients with serious and persistent mental illness. Criteria must be developed to determine which sex offenders are more appropriate for outpatient programs and to provide a rational basis for transitioning patients from institutional to outpatient care. Civil commitment to outpatient treatment may provide a more appropriate level of care for many patients than psychiatric hospitalization in traditional general inpatient settings.

Finally, from a scientific standpoint, there remain significant problems with the available data from sex offender treatment studies. An optimistic perspective must be entertained cautiously and accompanied by a commitment to the advancement of scientific knowledge in the field. This perspective is not new to psychiatry, where gains in knowledge about treatment of chronic illnesses such as schizophrenia have been gradual and hard earned. Yet as Bradford (

66) recently pointed out, support for the scientific study of deviant sexual behavior has not kept pace with the apparent—or at least official—public sentiment about the management of sexual aggressors. It would be informative for such research to include a focus on sex offenders from additional populations, such as women and adolescents.

Treatments for sex offenders do exist, and the outcome data are not uniformly discouraging. They are, however, complex, difficult to interpret, and cause for cautious optimism at best. If mental health professionals and society at large are to accept the challenge of promoting treatment for sex offenders, vigorous ongoing research efforts are mandatory.