Providing housing for homeless mentally ill persons is an essential foundation for their community reintegration and for effective provision of services to them (

1,

2). However, little empirical research has been conducted to determine what type of housing minimizes the risk of further homelessness, which individual characteristics contribute to further homelessness, or whether particular types of housing are more likely to minimize the risk of homelessness for persons with certain characteristics.

The kinds of housing available to homeless and formerly institutionalized mentally ill persons range from independent apartments to highly staffed group homes (

3). Most homeless individuals with chronic mental illness indicate a preference for independent living, but their family members and service providers are much more likely to recommend placement in staffed group homes (

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9). Research findings are divided about the value of different housing options (

10,

11,

12), although most observers agree that multiple options should be available to accommodate different levels of functioning (

13). Published research has suggested that a combination of housing and on-site services improves residential stability, but comparative analyses have not been conducted to distinguish the effects of housing itself from the effects of services (

1,

14,

15,

16).

The study reported here compared housing outcomes for 118 homeless mentally ill individuals who were randomly assigned to live in either independent apartments or staffed, group homes. We hypothesized that those who are placed in staffed group housing would experience fewer subsequent days of homelessness than those placed in independent apartments, due to the lower level of support—from both other residents and house staff—available in the independent apartments. Based on earlier research on housing loss and residential instability, we also hypothesized that certain individual characteristics would be associated with number of days subsequently homeless, including younger age, male gender, less education, a diagnosis of schizophrenia, and a history of abuse of alcohol or other drugs (

14,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27). Finally, we examined the consequences of consumers' housing preferences and clinicians' housing recommendations on the number of days homeless, giving particular attention to consumers whose preferences were discrepant with the type of housing they received.

We expected that the effect of housing type on subsequent homelessness would vary with individual characteristics. In general, we anticipated that consumers who had clinical, demographic, or other features associated with a higher risk of homelessness would experience even more days homeless if placed in an independent apartment than in staffed group housing. We tested for interactions involving housing type and each of the potential predictors of the number of days subsequently homeless.

Methods

A total of 303 residents of shelters for homeless mentally ill persons in Boston were identified initially as eligible for the study and were screened for dangerousness between January 1991 and March 1992. Sixteen individuals were excluded because they were not able to speak and understand English or because they were not mentally ill. Ninety-one were deemed unsafe for placement because they seemed to be at imminent risk of danger to themselves or others if placed in an independent apartment (

28). Of the remainder, 156 individuals provided informed consent to participate in the study after it was described to them in detail.

Ultimately, 118 individuals were randomly assigned to group housing sites (N=63) or independent apartments (N=55). The remaining 38 found alternative accommodations during the waiting period before placement. There were no statistically significant differences between individuals assigned to the two housing types in the characteristics examined in this study.

The independent apartments were efficiency units operated by the Boston Housing Authority. The apartment sites offered a voluntary weekly group but no other on-site programming or clinical staff. The seven group homes each accommodated between six and ten tenants with shared living, dining, recreational, and kitchen facilities, but separate bedrooms. These houses began with a staffing pattern resembling that of traditional group homes, with 24-hour daily coverage, but project staff encouraged residents to take over household decision making. We termed these consumer-directed residences "evolving consumer households."

All study participants were provided with an intensive case manager whose services were funded by the research project. Each participant met with the case manager at least once a week for counseling, hands-on help with daily activities, and help with access to needed services. Study participants in the evolving consumer households had much more opportunity to receive additional support due to the daily presence of house staff. All study participants paid 30 percent of their income for rent and utilities at all placement sites, and all were encouraged, but not required, to participate in community mental health center programs after they were housed.

Study participants

Of the 118 study participants housed, 72 percent were men, 70 percent had never married, and 41 percent were African American. Their average age was 38 years. About two-thirds had completed high school or had a general equivalency diploma. However, only 14 percent were employed; all of them worked part time. Eighty-six percent received income from only the Supplemental Security Income or Social Security Disability Insurance programs.

Psychiatric medication was prescribed for 90 percent of the study participants, and 83 percent reported having been hospitalized for psychiatric reasons at least once. Most—77 percent—had been arrested or jailed at least once. The most common primary psychiatric diagnoses identified by researchers using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R were schizophrenia for 45 percent of study participants, schizoaffective disorder for 17 percent, bipolar disorder for 14 percent, and major depression for 13 percent. Eighty-eight study participants also had significant lifetime secondary axis I diagnoses, with about half identified as abusing alcohol or other drugs.

Follow-up data covering 18 months were available for 110 study participants. At 18 months, three of the original 118 study participants had died, three had moved out of state, and two who were initially assigned to independent apartments were excluded from the analysis because, by law, their criminal records precluded their being randomly assigned to live in apartments operated by the Boston Housing Authority. The 110 study participants included one who died 16 months into the project; his final residential status is coded as of 16 months. Study participants for whom follow-up data collection was not complete did not differ significantly at baseline on any measure from those who completed the follow-up.

Measurements

Data on psychiatric diagnosis, substance abuse, residential preference, clinician housing recommendation, and several social background indicators were collected at baseline. The number of days of homelessness was recorded for the entire follow-up period.

Study participants' housing status was identified using their self-report, records of the housing facilities involved in the research project, records of the Department of Mental Health, and weekly logs completed by the case managers. From these sources, we constructed a housing timeline that indicated the time spent by each study participant in project housing, in other community housing, in shelters, on the streets, and in institutional settings such as hospitals, detoxification centers, or jails, as well as the housing status at the end of the follow-up period. These data were compiled even for study participants who left project-sponsored housing or withdrew from active participation in follow-up research. We focus in this analysis on the number of days study participants were homeless during the 18 months of follow-up.

Clinical status measures included psychiatric diagnoses made by a trained clinical psychologist using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)—Patient Edition (

29). As a test of interrater reliability, another psychologist assessed a subset of seven cases. The two clinicians agreed on the primary diagnosis in all seven cases and on the secondary diagnosis in six of the seven cases. In this paper we distinguish study participants who had schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder from those with other diagnoses, almost all of which were major affective disorders.

Drug and alcohol abuse was measured at baseline using the alcohol and psychoactive substance modules of the SCID. Study participants were asked to base their responses on the worst period of substance use in their lifetime. The levels of substance use considered in the analysis were based on the SCID categories of abuse, some use, and nonuse (

30).

Consumers' residential preference was measured with an index that combined answers to questions about preference for living with others and for on-site staff support. The internal consistency of the index was good (Cronbach's alpha=.72) (

8). Items in the index had from one to five response choices, which were scored so that the high and low response in each case was 1 or 5.

A measure of clinicians' residential recommendations was constructed from the ratings made by two clinicians of each consumer's readiness for independent living. The ratings were made at baseline by clinicians with extensive experience in community placements. The clinicians' answers to nine questions, each of which was scored on a 5-point scale, were averaged together, and then these nine scores were themselves averaged. Internal consistency for the measure of residential recommendations was good (Cronbach's alpha=.84) (

5). The correlation between the two clinicians' ratings was .43.

Social background variables were age, race (minority or white), gender, and education. Individuals who had earned a general equivalency diploma in lieu of a high school diploma were credited as having 12 years of education.

Data analysis

Due to the skewed distribution of the number of days homeless among the study participants, we focused our analysis on the log (plus one) of the number of days homeless. This strategy was used to reduce the skew in the distribution, thereby to more closely approximate the assumptions of regression analysis. One was added to the log of the number of days because the log of zero is undefined. We began with a t test of the mean difference between the log of days homeless for the two types of housing. We then did a regression analysis to examine the relationship between days homeless, housing type, and the other hypothesized predictors. We also tested every predictor for an interaction with housing type, using product terms entered in the last stage of the regression analysis, after centering the component variables to reduce the threat of multicollinearity (

31). A final multiple regression model included the one statistically significant interaction with housing type.

Results

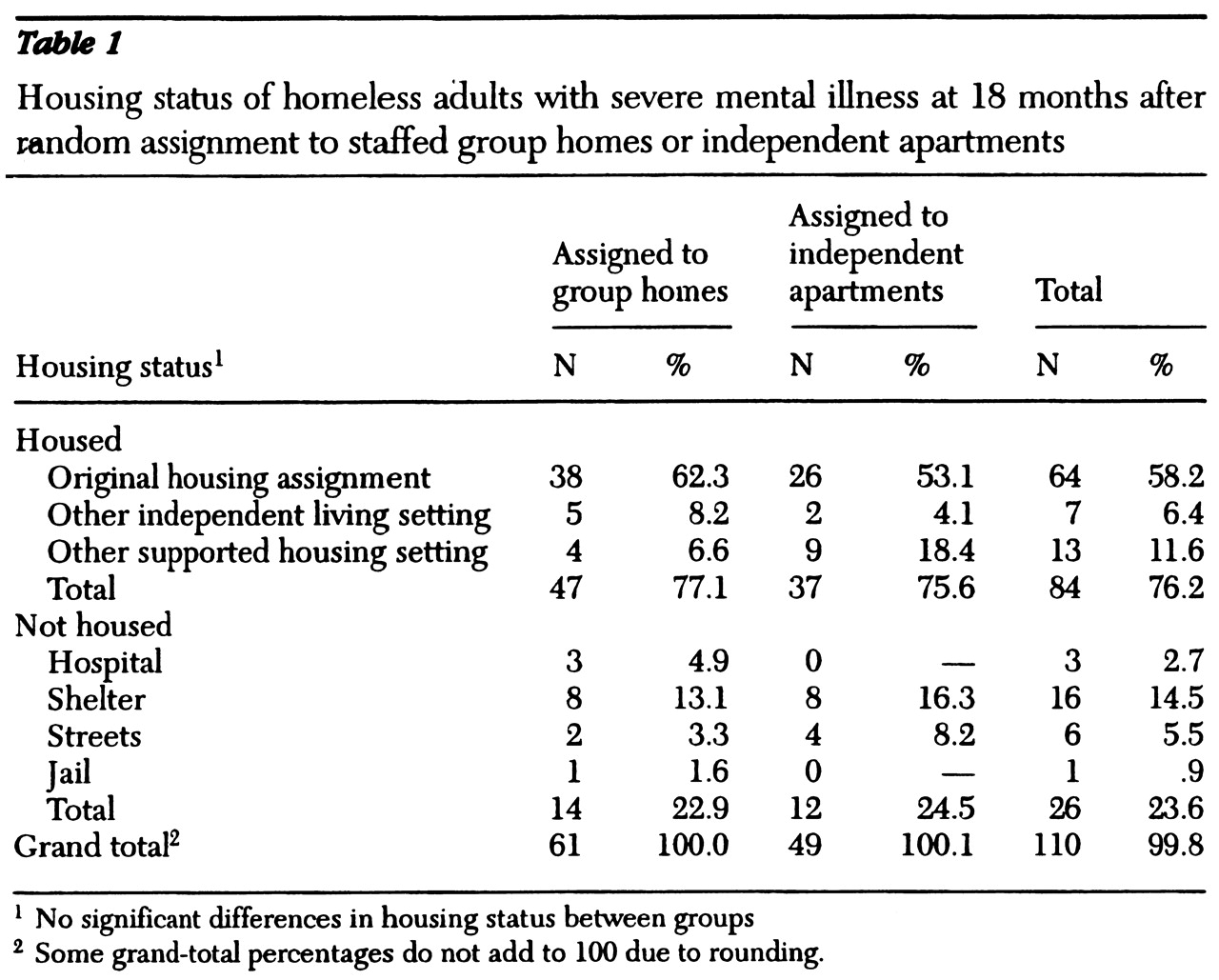

Most study participants, or 76 percent, were in community housing of some sort at the end of the 18-month follow-up period, with no significant differences between the percentage in group homes (evolving consumer households) and the percentage in independent apartments.

Table 1 summarizes these data. However, such a cross-sectional point-in-time view does not capture vulnerability to housing loss and does not distinguish between those who may have spent significant periods without housing from those who remained continuously domiciled.

Our more sensitive measure of housing loss, total days homeless after rehousing, showed significant differences between housing types. The log of the number of days homeless at any time during the project differed in the hypothesized direction between the two housing types (log [+1]=.99 for 61 study participants in group homes compared with 1.8 for 51 study participants in independent apartments; t=-1.85, df=97 [unequal variances], p<.05, one-tailed; log [+1]=1.37 for the 112 study participants in both groups) (

32). A total of 26.8 percent of all study participants experienced homelessness at some time during the project; 19.7 percent of the study participants assigned to the group homes had periods of homelessness, compared with 35.3 percent of those assigned to the independent apartments (χ

2=3.46, df=1, p<.05, one-tailed). The mean number of days homeless was 59, representing 10 percent of the total follow-up period. Study participants assigned to independent apartments had a mean of 78 days homeless, and those assigned to the group homes had a mean of 43 days homeless.

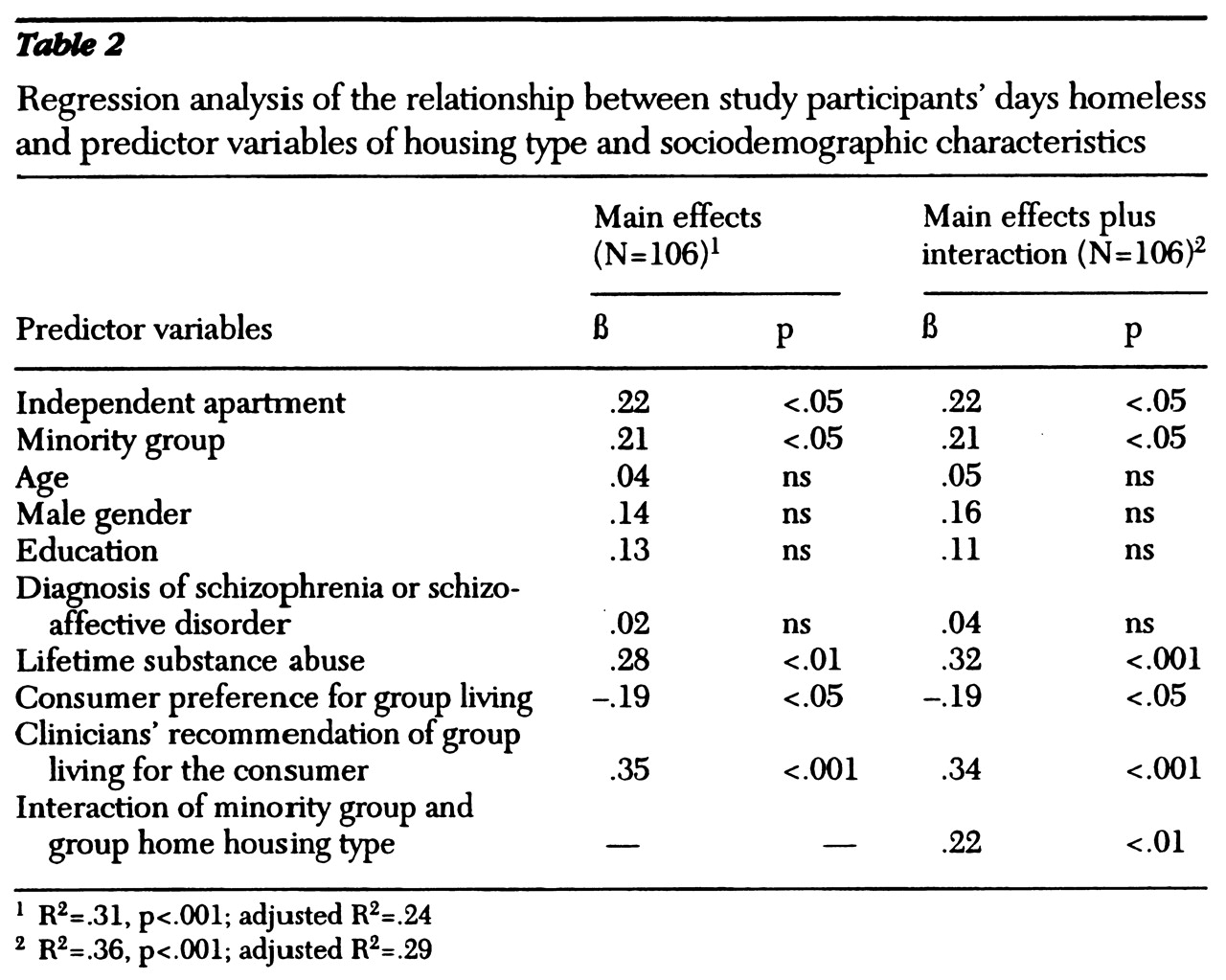

Housing type was also a significant predictor of days homeless in the multiple regression analysis. In addition, as hypothesized, lifetime substance abuse was associated with more days homeless, as was minority ethnicity (see

Table 2).

Measures of consumer and clinician housing preference helped to predict the number of days homeless. The stronger the clinicians' recommendation at baseline against the study participant's independent living, the more days the study participant subsequently spent homeless. Conversely, the stronger the study participant's baseline preference for independent living, the more days he or she subsequently spent homeless.

The test for interactions between the independent variables and housing type identified only one significant effect. Consumers who were African American or Hispanic experienced disproportionately more days homeless if—but only if—they were assigned to independent housing. Inclusion in the regression of a centered product term representing this interaction increased the proportion of variance explained from .31 to .36, but did not alter the effects of the other variables.

The interaction between race, housing type, and actual days homeless was analyzed without controlling for the other predictors. Study participants from minority groups who were assigned to independent living experienced a mean±SD of 107±26 days homeless during the follow-up period, compared with 51±29 days for those assigned to staffed group housing. Among white study participants, the mean±SD numbers of days homeless were 48±25 for those assigned to independent apartments and 36±32 for those assigned to group homes.

Discussion and conclusions

Perhaps this study's most important finding is that more than three-quarters of the homeless individuals with severe mental illness who participated in the study were still living in community residences at the end of 18 months. This rate of housing retention is comparable to rates that have been achieved in other interventions combining services and housing for this population and indicates the potential of such interventions for improving residential stability (

1,

15,

33,

34). All participants in our study received safe and affordable housing as well as the assistance of specially trained case managers. In the absence of comparable supports, housing retention rates may not be as high.

These results may not generalize to homeless mentally ill persons who are extremely disordered or more globally resistant to clinical interventions. All study participants were living in service-oriented shelters, and one-third of potential study participants were screened out because they were deemed potentially dangerous to themselves or others if they were randomly assigned to independent apartments. Those who refuse to live in shelters or who have resisted mental health services may be less likely to remain in any type of housing placement. We also cannot discount the possibility that study participants' success was partly shaped by a "Hawthorne effect" related to their awareness of being involved in a large research project (

35).

Our hypothesis that study participants residing in staffed group housing would experience fewer days of homelessness was supported, although the difference in outcomes between housing types after 18 months was not large. We expect that the difference in housing stability between study participants assigned to staffed group homes and those assigned to individual apartments is likely to be greater in more typical residential placements, over a longer follow-up, and in the absence of intensive case management.

The independent apartments in this study were all in buildings operated by a public housing authority, where on-site building managers could respond directly to problems involving residents. Apartment buildings available to clients on the private market are unlikely to offer even this degree of support. Our staffed group housing provided consumers with much more autonomy than is typical in group homes. The 18-month follow-up period undoubtedly did not identify all consumers who would eventually become homeless. The intensive clinical case managers who were available to residents in both housing types—and whose services were used to an equivalent degree by both groups (

36)—are often not provided in typical community placements.

The significant difference we found in the number of days homeless between subjects in the two housing types was limited to study participants from minority ethnic groups and was accounted for by minority participants who were assigned to independent apartments. We could find no other clinical or demographic variable that further explained this finding and no further interactions involving race and housing type that might elucidate it. The effect of race may have been due to differences in the treatment of minority tenants by landlords or to different patterns of substance use and abuse. However, neither examination of housing loss by neighborhood nor analyses that controlled for type of substance abused help to explain this racial difference.

Other research that has attempted to identify the influence of race on housing outcomes has provided little support for any particular explanation. Race was unrelated to change in living arrangements among discharged inpatients with schizophrenia during a one-year follow-up study in Manhattan (

22). Race did not predict housing status in a two-year follow-up study of initially homeless older women in New York City (

37). In a California study with varying follow-up intervals, homeless African-American single men were more likely to remain homeless than men of other racial groups, and African-American women were more likely to return to homelessness after being rehoused than were other women (

38).

However, members of minority groups are disproportionately represented among the homeless population in most cities (

39), and those who are consumers of mental health services tend to receive lower-quality housing (

40). We suggest that researchers give special attention to identifying the possible structural, personal, and local political factors that create this vulnerability.

Study participants who abused substances were clearly more vulnerable to further homelessness. Providing appropriate treatment options (

41) should be the first step in enhancing support for these consumers. We know that our housing interventions did not offer the specific services that are most often recommended for substance abusers, such as meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous or training in relapse prevention. In fact, alcohol use was not administratively prohibited in the residences; residents themselves developed policies regulating substance use in their homes after they encountered problems stemming from substance abuse. Acceptance of any form of treatment was voluntary in our study. Substance abusers knew that refusing to participate in substance abuse treatment programs would not, in and of itself, jeopardize their housing, and many simply refused such interventions.

Our findings on the effect of consumer preferences inform, and further complicate, the debate in mental health services over how best to include consumer choice in decision making. We strongly support the need for clinicians to pay close attention to consumer preferences in all treatment interventions. However, we found that study participants who were more in favor of living independently tended to experience more days homeless (

5,

8). Thus our findings suggest that considering only consumer housing preferences, without paying attention to other factors, will not improve housing outcomes.

The housing recommendations of experienced clinicians did seem to be relatively good predictors of subsequent risk of homelessness, even though this relationship did not vary with the type of housing actually obtained. Additional research is needed to determine whether newly developed housing options can reduce the number of days homeless by including features that provide both the independence that consumers want and the specific sorts of support that clinicians believe the consumers need.

Psychiatric diagnosis did not predict housing loss. This finding may be due to the relatively high levels of services available to all study participants but more likely underscores the need to distinguish psychiatric diagnosis from functional impairment. None of the other hypothesized predictors of days homeless had significant effects, suggesting the limited generalizability of previous findings.

Our research design did not distinguish the particular features of the two housing models that made a difference in housing outcomes. Further research should be designed to differentiate the effects of having residential staff from those of having roommates and to identify differences between living in an apartment building with an on-site manager and living entirely independently. Ongoing observation of group home social interaction should help identify the mechanisms through which the group experience reduced the likelihood of housing loss. Investigations with longer follow-up periods are also needed to determine whether staffing can be eliminated in most group homes after an extended preparatory period.

Most important, we believe we have shown that studies of housing loss must take into account the type of housing that consumers have received as well as the characteristics of the consumers themselves. Service policies that maximize housing retention cannot be formulated until we have a clearer understanding of how consumers with different needs respond to particular types of housing.

Acknowledgments

The Boston McKinney Research Demonstration Project was funded by grant R18-MH-4080-05 from the National Institute of Mental Health and received extensive support from the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health and the Boston Housing Authority. The authors thank Herbert L. Costner, Ph.D., Barbara Dickey, Ph.D., Joseph Hogan, Ph.D., Judi Chamberlin, Laura van Tosh, and the late Howie the Harp for their advice and expertise.