Measures of patient satisfaction have become a standard component of assessments of quality in health care (

1). Satisfaction measures are used in virtually every system of health care evaluation, and the results are used to promote services to potential customers.

Despite the widespread use of patient satisfaction as a measure of quality, methodological problems with the interpretation of satisfaction measurements persist. For example, many studies have indicated that global satisfaction measures are affected by many factors other than the quality of service delivery, including patients' demographic characteristics (

2,

3), diagnosis (

1,

4), treatment program (

5), and chronicity of disease (

4).

As these methodological issues have become more widely recognized, some health care systems have developed ways to adjust for such factors in examining satisfaction measures. However, there may be some subgroups of patients for whom relative satisfaction is a less accurate reflection of quality of care (

5,

6). When this paper was written, only one study had examined how mental illness affects satisfaction (

7). That study compared samples of Medicare beneficiaries with psychiatric and nonpsychiatric diagnoses who received health care services in an integrated health care system. Compared with patients who had a nonpsychiatric diagnosis, patients with a psychiatric diagnosis were less satisfied with their overall care, their follow-up care, and their perceived level of the physician's concern with their health.

The study reported here examined the role of psychiatric diagnosis in determining satisfaction with inpatient care provided by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system. In addition, we explored whether the type of treatment program—a mental health or psychiatric treatment program versus treatment on a medical unit—differentially affected the association between diagnosis and satisfaction.

The literature has suggested several reasons to hypothesize that psychiatric diagnosis may be an important determinant of satisfaction measures. Greenley and colleagues (

6) suggested that psychologically distressed patients may be less satisfied with their health care because their distress may cause them to be dissatisfied with many aspects of their lives. In addition, service providers may react negatively to psychologically distressed patients, and patients' perceptions of these reactions could be reflected in lower satisfaction scores (

8).

Although these hypotheses were based on measures of psychological distress and not psychiatric illness, other research has indicated that patients with chronic illnesses tend to be less satisfied with their care than those with acute problems (

4). This finding implies that patients with chronic psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia or bipolar depression could have lower levels of satisfaction with their care for reasons having little to do with the objective quality of care (

1).

The study used data from a national sample of veterans discharged from VA hospitals to compare the satisfaction of patients with psychiatric diagnoses and those with nonpsychiatric diagnoses. We addressed three questions. First, are patients with a psychiatric diagnosis less satisfied with their care than those with a nonpsychiatric diagnosis? Second, are patients treated in mental health or psychiatric treatment programs less satisfied than those treated in medical units, regardless of diagnosis? And third, are these relationships dependent on other patient characteristics such as soc iodemographic characteristics, subjective assessment of health, or disability?

Methods

Sample

The sample consisted of respondents to a large customer feedback survey that has been conducted annually by VA since 1993 (

8,

9). The survey was directed to a random sample of VA inpatients who were discharged to the community from VA medical centers between June 1 and August 31, 1995. The sample was selected to target 175 medical, surgical, and psychiatric patients from each hospital, with the goal of obtaining a sample of 105 responses from each service at each facility.

Patients in the sampling frame were identified by discharge abstracts in VA's decentralized hospital computer program, a computerized workload database in operation at each VA hospital; it is used to compile the national patient treatment file, which includes discharge abstracts for all episodes of VA hospital care. Data on age, gender, race, marital status, receipt of VA compensation payments, primary diagnosis, and length of stay were obtained from these files for all patients in the sampling frame. Descriptive data, but not patients' names, were linked with codes on each returned questionnaire.

Survey methods

Data were collected using a mail-out-mail-back methodology. A letter was sent out to each veteran one week before the actual survey. The questionnaire was sent out with a cover letter from the director of VA's National Customer Feedback Center and the VA undersecretary for health assuring respondents that their responses would not be linked to their names and would not affect their eligibility for VA benefits in any way. Follow-up contacts consisted of a postcard reminder and, if that did not result in a response, a repeat mailing of the entire questionnaire.

A total of 66,177 surveys were mailed to patients. The overall response rate of 58 percent was high, but patients with a psychiatric diagnosis had a lower response rate (39 percent) than those without such a diagnosis (65 percent) (χ2=3,586.66, df= 1, p=.001). Those less likely to respond to the survey included women (56.32 percent, compared with 58.54 percent for men; (χ2=4.41, df=1, p=.036), nonwhite patients (45.6 percent, compared with 62.31 percent for white patients; (χ2=1,349.41, df=1, p<.001), and single or never-married patients (48.75 percent, compared with 61.03 percent for married patients; (χ2=679.98, df=1, p<.001).

In addition, patients who were less likely to respond included those with longer mean lengths of hospital stay (8.33 days, compared with 6.62 days for respondents; t=776.46, df=1, p<.001), patients who received disability payments (57.79 percent, compared with 59.66 percent for patients who did receive disability payments; (χ2=21.9, df=1, p<.001), and patients who lived a closer mean distance to a VA facility (1.9 miles for respondents, compared with 2.12 miles for nonrespondents; t=776.46, df=1, p<.001). Respondents were also older; their mean age was 60.96 years, compared with 54.56 years for nonrespondents (t=3,344.25, df=1, p<.001). The sample size for these analyses included all survey respondents, or 38,789 respondents.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire consisted of two sets of questions that covered each veteran's most recent hospitalization. One set, comprising 43 items, was derived from a general health care questionnaire developed by the Picker Institute of Boston (

10). The second set, which consisted of 36 items, was derived from specific mental health care instruments and was asked only of people who had been hospitalized in a psychiatric treatment program. Only the first set of questions was used in the analyses presented here.

The Picker Institute questions addressed nine general areas of satisfaction, each of which was measured using a subscale of three to six items. The nine areas addressed were coordination of care among providers, open sharing of information with the patient, timeliness and accessibility of services, courtesy of staff, emotional support, attention to patient preferences and to involving the patient in decision making, quality of family involvement and participation in care, physical comfort and attention to physical needs, and help with the transition from the hospital to outpatient status.

Responses were coded on ordinal scales with 0 representing the least satisfaction and 1 the greatest satisfaction. Thus if an item had five response levels, the levels would be coded from 0 to 4 and the total divided by 4. An overall measure of satisfaction was calculated by averaging the average scores of the items in each subscale, which resulted in an average satisfaction measure weighted for the number of items in each subscale.

Variables of interest

The independent variable of interest was whether the respondent had been discharged from the hospital with a psychiatric or a medical diagnosis. The group discharged with a psychiatric diagnosis was further divided into two subgroups, those who were discharged from a psychiatric treatment program and those who were discharged from a medical unit. These variables were constructed using administrative data on discharge diagnosis and bed section.

Other variables of interest included age, gender, race (white, black, Hispanic, or other), marital status (married, never married, or previously married), disability status as measured by a percentage disability rating, global health rating (excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor), length of the hospital stay in days, annual income, and distance from the respondent's home to the nearest VA hospital. These data were taken either from the survey itself or from computerized administrative data.

Analyses

Analyses proceeded in several steps. First, satisfaction ratings were compared across sociodemographic and health variables to determine which variables were significant predictors of satisfaction ratings. Second, linear regression models were fit to predict satisfaction ratings. An unadjusted model with a mental health diagnosis as the independent variable was produced first, and then a second model that adjusted for all other significant predictors of satisfaction was produced. Third, to determine whether psychiatric diagnosis influenced satisfaction in certain sociodemographic subgroups but not others, interaction terms consisting of mental health diagnosis and either age, race, marital status, or gender were tested. Finally, linear regression models were fit separately for each satisfaction subscale to determine if observed overall patterns were explained by particular domains of satisfaction.

Standard procedures for regression analysis required that the length of hospital stay needed to be log transformed to satisfy normality assumptions. No other weaknesses in the fit of the models were identified.

Results

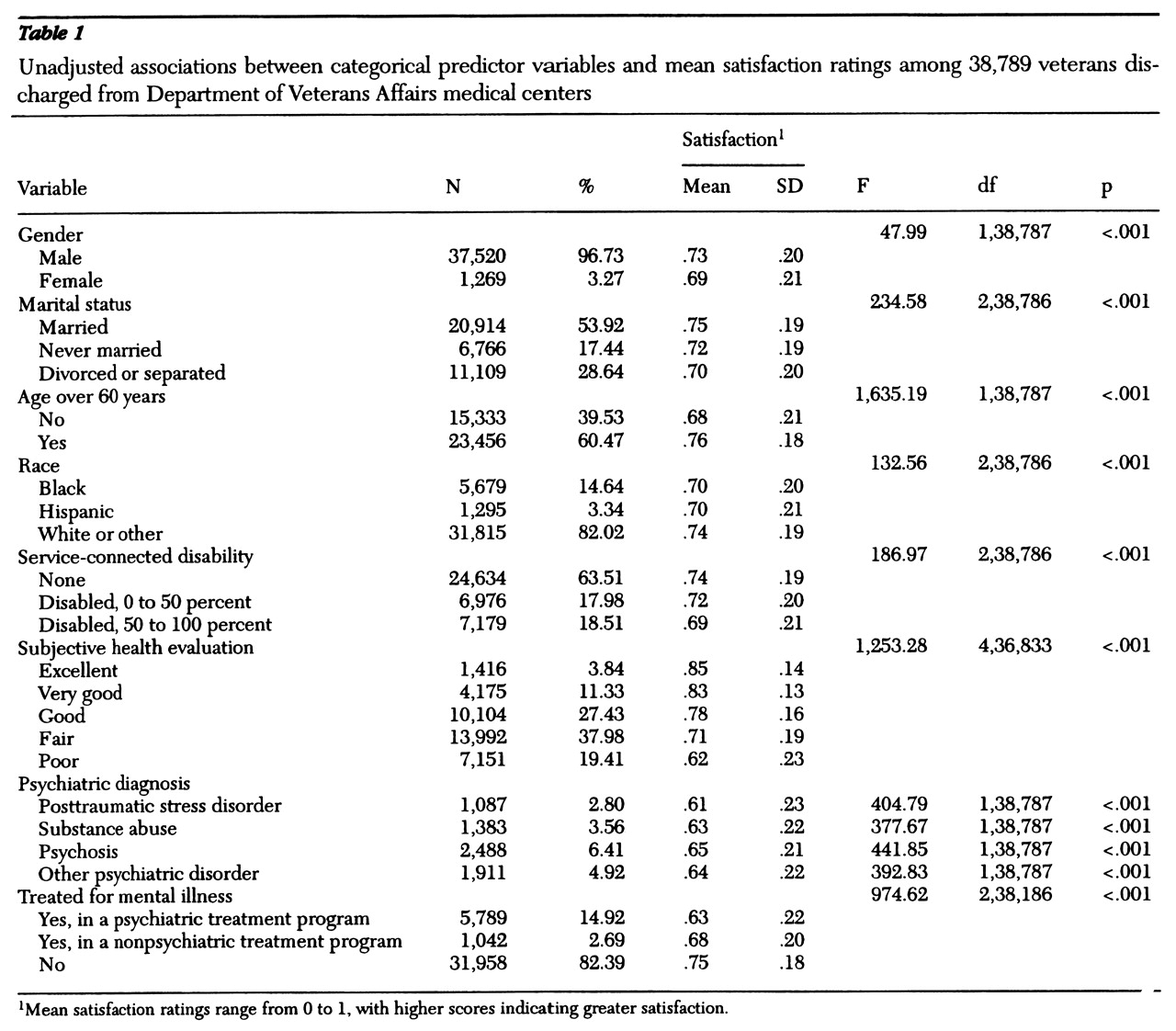

Table 1 presents the mean satisfaction ratings for categorical variables. Higher average satisfaction ratings were found for respondents who were male, married, older, and white. Those who were receiving disability compensation payments, had lower health ratings, or had a mental health diagnosis had lower mean satisfaction ratings.

We also calculated correlations between satisfaction and the continuous variables of interest. Higher satisfaction was correlated with shorter lengths of stay (r=-.07, p<.001), higher income (r=.03, p<.001), and living farther away from the VA hospital (r=.05, p<.001).

The analyses indicated that the variables included in these correlations and those shown in

Table 1 were significant predictors of satisfaction and thus could potentially confound the relationship between mental illness and satisfaction.

Pairwise comparisons indicated that although each of the two subgroups with a psychiatric diagnosis—those discharged from a medical unit and those discharged from a psychiatric treatment program—had significantly lower levels of satisfaction than those without a psychiatric diagnosis, they were not significantly different in satisfaction from each other. Mean±SD satisfaction ratings were .63±.22 for those treated in a psychiatric program and .68±.20 for those treated in a medical unit.

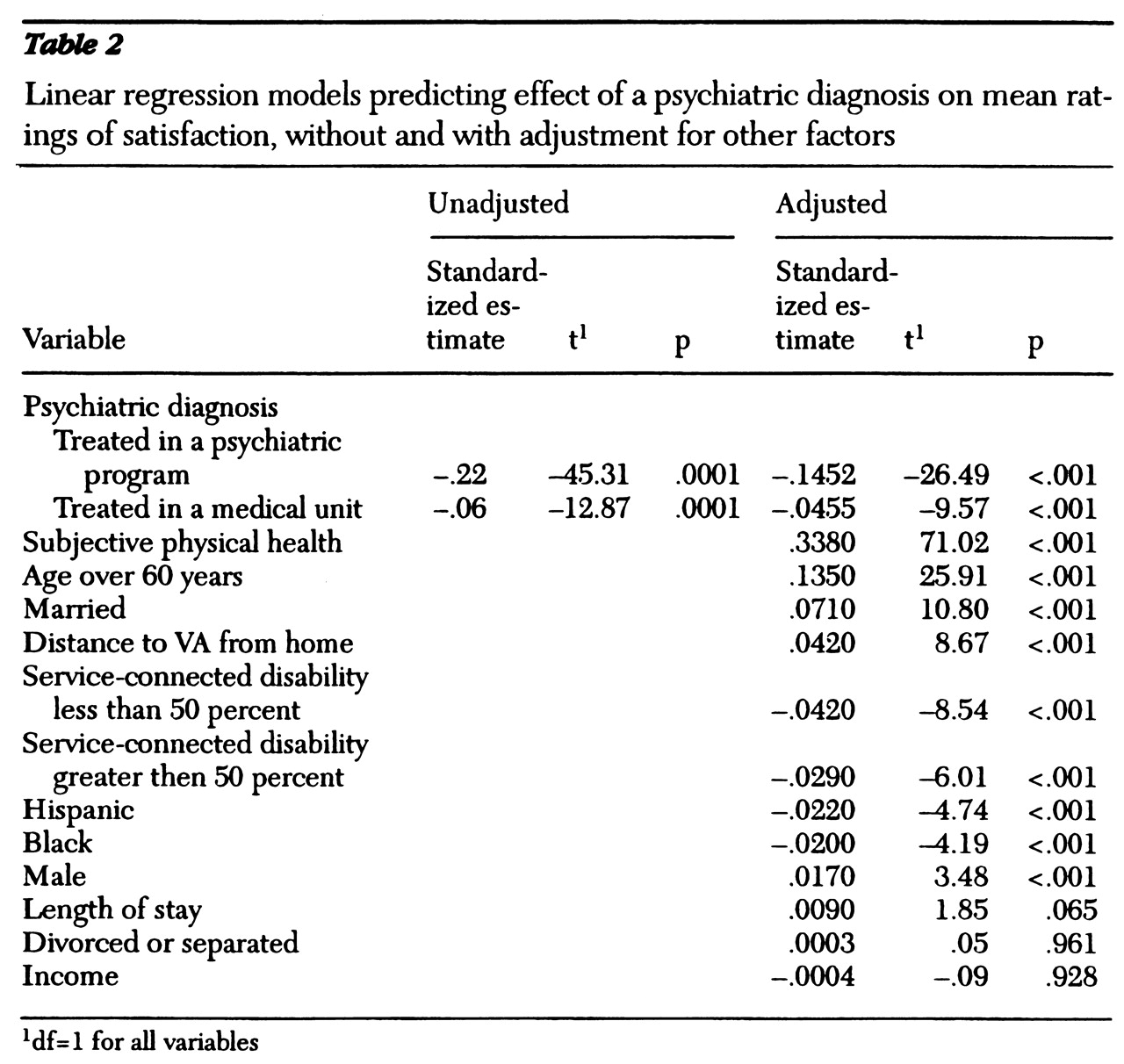

Table 2 presents two linear regression models predicting satisfaction, one that is unadjusted for other potential confounding variables and one that is adjusted. In both models, patients with a psychiatric diagnosis had lower satisfaction ratings than those without a psychiatric diagnosis, although the effect was reduced by about 40 percent after the analysis adjusted for other predictors of satisfaction. This pattern was particularly true of patients treated in a psychiatric program. In fact, having a mental health diagnosis and being treated in a psychiatric program was the third strongest predictor of satisfaction, after age and subjective physical health.

The next stage of the analysis involved testing interactions between mental health diagnosis, treatment program, and age, gender, race, and marital status. A significant interaction was found between psychiatric diagnosis, treatment program, and race (F=11.51, df=1,38,746, p<.001). Nonblack respondents were consistently less satisfied with their care, but those who were discharged with a psychiatric diagnosis were more dissatisfied. The mean satisfaction ratings of respondents with nonpsychiatric diagnoses were .71 for nonblack patients, compared with .72 for black patients. Among respondents with a psychiatric diagnosis who were treated in a psychiatric program, the mean satisfaction ratings were .64 for nonblack patients and .66 for black patients. Among respondents with a psychiatric diagnosis who were treated in a medical unit, the mean satisfaction ratings were .65 for nonblack patients and .68 for black patients. No significant interaction was found between psychiatric diagnosis and treatment program.

The final analysis examined each subscale of the satisfaction measure to determine whether the lower overall satisfaction ratings among patients with a psychiatric diagnosis could be explained by lower satisfaction with specific aspects of care. In addition, the specific diagnoses of patients with a psychiatric disorder were examined to determine if the lower satisfaction ratings could be explained by lower ratings among patients with particular disorders.

Lower satisfaction ratings were consistently found among patients with a psychiatric diagnosis on every subscale of satisfaction. For example, patients with a psychiatric diagnosis had a mean satisfaction rating of .6 for family involvement in care, compared with .68 for patients with a medical diagnosis (t=1,006.2, df=1, p<.001). For coordination of care, patients with a psychiatric diagnosis had a mean satisfaction rating of .76 compared with .79 for patients with a medical diagnosis (t=667.78, df=1, p<.001). In each domain, those with a psychiatric diagnosis were significantly less satisfied, indicating that no specific domain explained the overall findings.

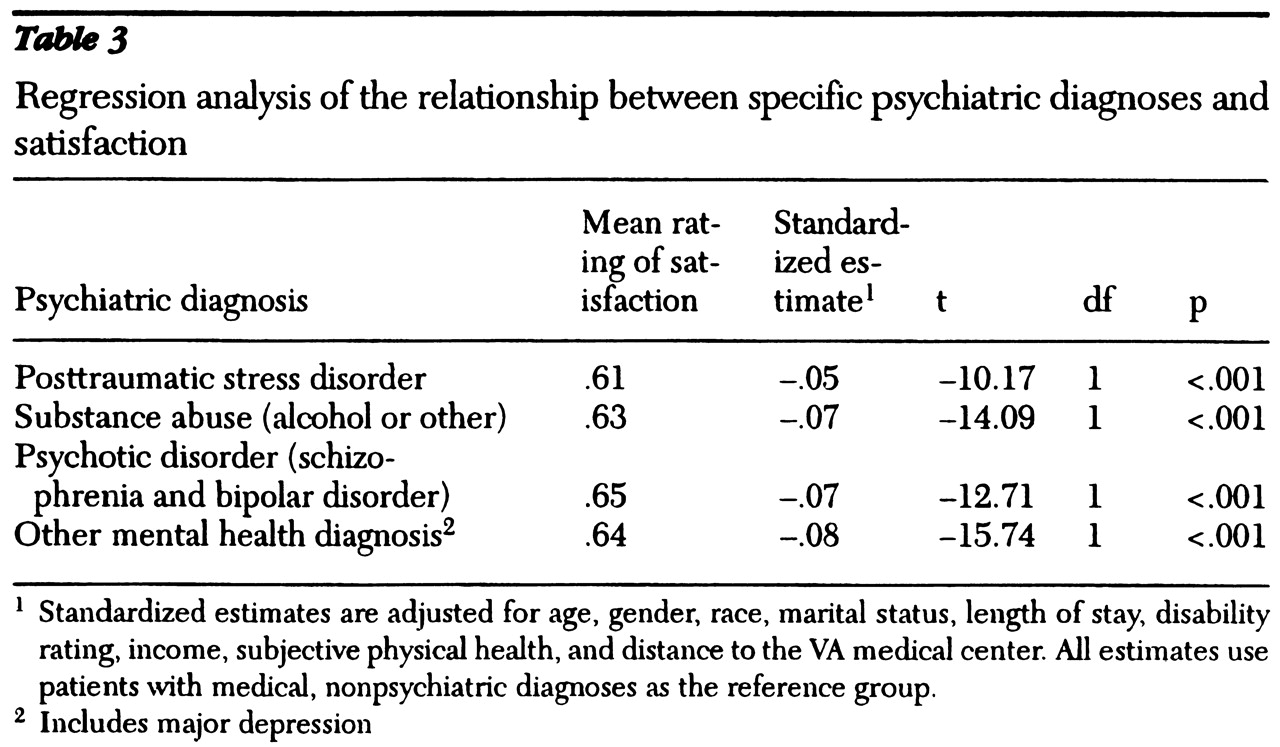

Similarly, as

Table 3 shows, lower satisfaction was consistently found among patients with all types of psychiatric disorders, indicating that no particular disorder explained the association between mental illness and lower satisfaction.

Discussion and conclusions

Our analysis of data from a large sample of patients discharged from VA hospitals who responded to a satisfaction survey suggests several findings. First, patients with a psychiatric diagnosis at discharge had lower satisfaction ratings than those with a medical diagnosis at discharge. Second, lower satisfaction ratings among patients with a psychiatric diagnosis were not significantly affected by whether patients were treated in a medical unit or in a psychiatric treatment program.

Third, the effect of a psychiatric diagnosis on satisfaction was found to be significant even after the analysis adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics and the variables of subjective health, treatment program, and access measures such as distance to the hospital. And fourth, the negative effect of a psychiatric diagnosis on satisfaction was found to be more pronounced among nonblack patients.

Study limitations

Before discussing the results further, several limitations need to be acknowledged. First, although the survey methodology for this study was standard and the overall response rate of 58 percent was adequate for this type of study, patients with a psychiatric diagnosis were less likely to respond to the survey than were patients without a psychiatric diagnosis. No differences were found between the characteristics of nonrespondents with a psychiatric diagnosis and nonrespondents without a psychiatric diagnosis. However, we were unable to compare clinical data on respondents and nonrespondents. It is likely that respondents with a psychiatric diagnosis were higher functioning than nonrespondents with a psychiatric diagnosis.

Second, some data included in these analyses were collected from administrative databases, which are vulnerable to reporting errors and omissions. However, such errors would be no more likely to occur in data about patients with a psychiatric diagnosis than in data about those with a medical diagnosis. Therefore, although these errors may attenuate some of the relationships we found, they are not likely to have led to a differential bias.

Predictors of satisfaction

All of the variables included in these analyses were significant predictors of satisfaction measures, a result that is consistent with other studies of patient satisfaction (

1,

10,

11,

12). However, these results clearly indicate that VA patients discharged with a psychiatric diagnosis are significantly less satisfied with their inpatient care. These results are consistent with an earlier study of psychiatric diagnosis and satisfaction (

7). This finding has several potential explanations.

First, mental health patients may be less satisfied with their care due to the nature of their illness. Psychological distress and psychiatric symptoms have been shown to be associated with general dissatisfaction and may not be specifically related to dissatisfaction with health care (

5,

6). The majority of VA inpatients with a psychiatric diagnosis either are acutely psychotic or are in substance abuse treatment. They are more likely to be inpatients against their will than are medical patients, are more likely to be treated in programs such as detoxification that are by their nature uncomfortable, and are more likely to suffer from disorders that are chronic and stigmatized. Lower satisfaction ratings could thus reflect psychological distress and frustration with the illness. This possibility is also supported by our finding that the type of treatment program was not a significant predictor of satisfaction and that no particular psychiatric disorders were associated with lower or higher satisfaction ratings.

The second possible explanation is related to the characteristics of the population served by the VA health care system. The VA cares primarily for veterans with disabling illnesses and those without financial resources for private health care. Previous studies have indicated that patients who are less satisfied with their care tend to disenroll from a care plan or to change providers (

13).

It is possible that those with a mental health diagnosis in this sample had few opportunities to change providers or get care elsewhere. The lack of opportunities could be due to lack of financial resources—those with a mental health diagnosis had significantly lower incomes than those with a medical diagnosis (t=219.78, df=1, p<.001)—or to the lack of needed services in a non-VA system. For example, medical services may be easier to obtain in the community than mental health services. As a result, patients with medical diagnoses who are dissatisfied with their VA care may have already removed themselves from the system, whereas dissatisfied patients with a psychiatric diagnosis may not have had the resources to change providers.

The final potential explanation is that the quality of care in VA mental health programs is indeed lower than the quality in other health care programs. This explanation seems unlikely for several reasons. First, patients who had a psychiatric diagnosis but who were treated in medical units had lower satisfaction than those treated in psychiatric programs. If the quality of care was lower in the psychiatric programs, we might expect satisfaction ratings to be significantly higher among patients with a psychiatric diagnosis who were treated in medical units. Second, no individual domains of satisfaction were unique in having lower ratings, and it is unlikely that lower quality would be pervasive across all domains.

Implications for practice and research

These results point to the need for caution when using satisfaction measures to compare quality of care across diagnostic groups or between programs treating patients with and without psychiatric diagnoses. The results suggest that those with a psychiatric diagnosis are likely to have lower satisfaction than other patients, even given similar quality of care, and that this lower satisfaction is most likely a function of their illness. It is thus difficult to interpret satisfaction ratings as an indicator of quality when comparing mental health and other health care programs, because the proportion of dissatisfaction that is due to the nature of the illness and the proportion that reflects true quality are unclear.

These results also point to several unanswered questions about satisfaction ratings among patients with a psychiatric diagnosis. First, few data are available in VA or public systems of care on the ability of patients to choose alternate care if they are dissatisfied. Future research should explore how patients with limited resources choose between VA and non-VA providers, and how those decisions are affected by their satisfaction with the care they have already received.

Finally, these results point to the need to combine subjective and objective measures of quality when evaluating programs or systems of care. Correlations between subjective and objective quality measures may indeed be lower in mental health treatment than in medical treatment, but this difference has not been empirically demonstrated. Until we have better data on how well subjective measures reflect actual quality of mental health care, systems and programs should be cautious about using satisfaction ratings as quality indicators without contextual objective quality measures.