Just as the number of older adults in the population has been increasing, the number of persons acting as the primary caregiver for an elderly patient with dementia has also grown (

1). The primary caregiving role is most often filled by the spouse of a patient with dementia, and recent studies have shown that spouse caregivers are subject to symptoms of clinical depression (

2,

3) and compromised immune function (

4,

5,

6). Thus far, psychoeducational programs targeting caregivers have been shown either to lessen depression, anxiety, and perceived burden or to have no effect on these variables (

3).

In the pilot study described here, women who were the primary caregiver for a spouse with dementia participated in an eight-week structured psychoeducational intervention designed to improve psychological and immune function. The study participants completed measures of mood, anxiety, perceived burden, and immune function at baseline, at the end of the intervention, and at follow-up one month after the end of the intervention.

Methods

Study participants

Eleven women who were the primary caregiver for a husband with dementia were included in the study. Six study participants were Caucasian, four were African American, and one was Hispanic. Their mean± SD age was 70±5.7 years, with a range from 62 to 81 years. Exclusionary criteria for the study included male gender, alcohol consumption of more than five drinks a week, and any medical condition that would significantly compromise immune function.

Procedure

Assessments.

The women who participated in the study signed consent forms approved by the human subjects committees at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and the University of California, Los Angeles. The study participants completed several self-report measures at baseline one week before the start of the psychoeducational intervention, at the end of the eight-week intervention, and 30 days after completing the intervention. The self-report measures were the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) (

7), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (

8), the Beck Anxiety Scale (

9), and the Zarit Burden Scale (

10).

At baseline, study participants were evaluated by the researchers using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) (

11). Study participants' husbands were evaluated using the MMSE at baseline and at the one-month follow-up. At the end of the intervention and at follow-up, participants were asked to rate how helpful they felt the program was to them.

In addition, study participants had 60 ml of blood drawn to measure immunologic parameters at baseline, at the conclusion of the intervention, and at the one-month follow-up. The analyses used change in T cell proliferation capacity in response to phytohemagglutinin antigen (PHA). Blood test results for three to six healthy young female control subjects (mean±SD age=34±7.4 years) were used to help standardize the immune assay results.

Intervention.

The psychoeducational group was co-led by a clinical psychologist and a social worker. The group met weekly for eight sessions, each of which lasted 90 minutes. In addition, the group leaders contacted each participant by phone once a week to reinforce the educational material provided during the group sessions and to provide additional support.

The psychoeducational group focused on building coping skills through stress reduction training, teaching cognitive-behavioral interventions to decrease depression and anxiety, providing information about resources for caregivers, and providing a supportive environment to address caregivers' current concerns. During the group sessions, a psychology intern provided day care for the study participants' husbands. The day care activity consisted of watching nature videos.

Analyses.

Statistical analyses comparing measures from baseline, completion of the intervention, and one-month follow-up included linear regression, Spearman's rank correlation, and Student's t tests, as appropriate.

Results

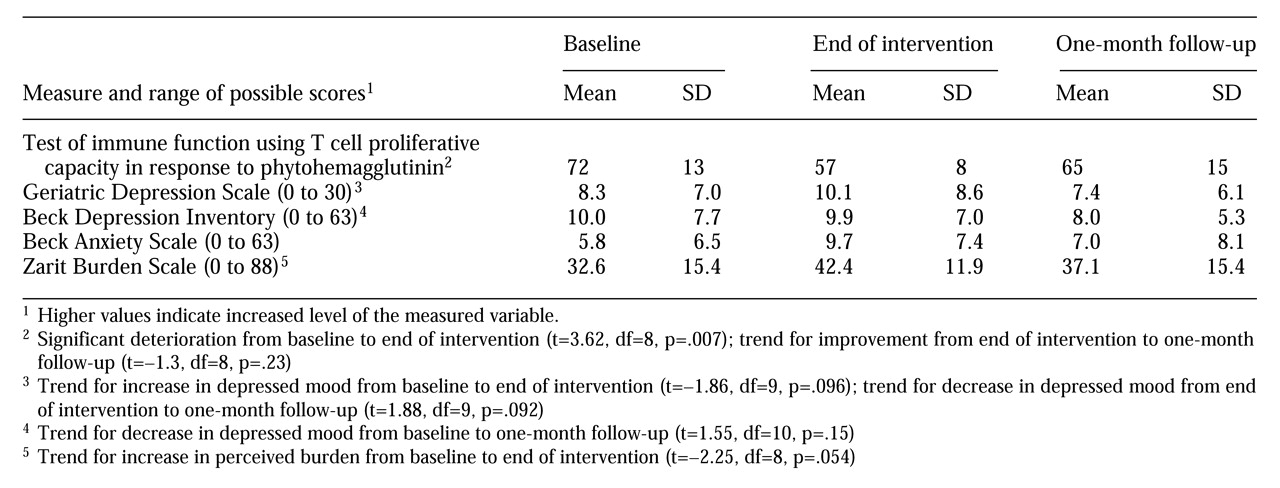

Table 1 shows study participants' mean scores on measures of immune function, depression, anxiety, and perceived burden. The participants showed a significant deterioration in T cell proliferation to PHA from baseline to the completion of the eight-week psychoeducational intervention, indicating a decline in immune status; the control group showed no fluctuation in immune function. Comparison of baseline and end-of-intervention measures also showed trends for increases in perceived burden as measured by the Zarit Burden Scale and depressed mood as measured by the GDS.

T cell proliferation to PHA at one-month follow-up revealed a trend for improvement from the end of the intervention. The mean GDS score was lower at follow-up than at baseline and showed a trend for improvement from the end of the intervention. Mean scores on the Zarit Burden Scale and the Beck Anxiety Scale improved from the end of the intervention to the one-month follow-up, but the changes were not significant. Mean scores on the BDI showed a trend for improvement from baseline to follow-up one month after completion of the intervention.

All 11 caregivers rated the group as "highly beneficial," a score of 5 on a 5-point Likert-type scale. Caregivers' scores on the MMSE were in the normal range (mean=28.6). Conversely, the mean MMSE score of the husbands declined significantly from baseline to follow-up (mean±SD= 13.27, compared with 9.22 at follow-up; t=2.85, df=7, p=.02).

Discussion and conclusions

Psychoeducational groups are frequently recommended for caregivers of patients with dementia. In the study reported here, it is noteworthy that the spouse caregivers had a significant deterioration in their immune function from baseline to completion of the psychoeducational intervention. The decline in immune status was associated with increases in perceived burden and depressed mood. However, all caregivers rated the treatment intervention as highly beneficial. The positive perception may reflect caregivers' relief at having time away from the burden of caring for their spouse with dementia.

Previous studies have established that caregivers of patients with dementia manifest increased levels of depression and perceived burden, along with reduced immune function (

1,

2,

3). Thus they are a group in need of treatment services to improve their emotional and physical health. However, the results of outcome studies of psychoeducational interventions for this group are mixed; some studies have shown a reduction in depression, anxiety, and perceived burden, and others have shown no effect (

3).

Several factors may have contributed to our study results. First, the psychoeducational process may be inherently stressful to spouse caregivers, because it increases awareness of the severity of their situation, and it may thereby initially worsen immune and psychological symptoms. Second, the caregivers' experience of the decline in function of their husband's mental state may have outweighed any beneficial effects of the program. Finally, the caregivers' anticipation of the loss of the weekly supportive group sessions might have contributed to the decline in immune and psychological function after the psychoeducational intervention was over.

Psychoeducational treatment for spouse caregivers that is not time limited, such as the ongoing support groups provided by the Alzheimer's Association, may help prevent the declines in physiological and psychological function noted in this study. Groups that are not time limited offer more opportunity to process information and feelings and may prove less acutely stressful for caregivers. The interaction of time in treatment with study outcome may help to explain why the study participants showed a trend for improved psychological and immune function at the one-month follow-up. In addition, individual psychotherapy has been reported to help some spouse caregivers of demented patients (

12).

The findings of this study, along with those reported in the literature, suggest that future research will benefit from random assignment of caregivers to specific psychoeducational or other treatment interventions and use of a control group for monitoring immune and psychological parameters. Future research will also have to address the extensive variation that currently exists in group treatments for caregivers, including variation in the duration of the interventions; the type and structure of group formats, such as psychoeducational versus supportive; and whether respite care is provided for the demented patient. Further research will help determine whether time-limited and focused psychoeducation for spouse caregivers may be inherently stressful, especially as the treatment process increases caregivers' awareness of their predicament.

In summary, the potential for psychoeducational groups to diminish caregivers' immune and psychological function, at least during early phases of treatment, is an area that requires critical examination in caregiving populations.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Geriatric Academic Program Award AG-00489-01 from the National Institute on Aging, the Department of Veterans Affairs Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center Service, and the UCLA Center for Interdisciplinary Research in Immunology and Disease.