Clients with serious mental illness typically report a low subjective quality of life (

1), and those who are homeless report even lower levels than those who are domiciled (

2). Fortunately, quality of life of homeless clients with serious mental illness has been shown to improve during participation in treatment (

3,

4). Lehman and associates (

2) suggested that the quality of life of persons who are homeless and have a serious mental illness may be improved by efforts to increase their access to public support income and social support networks. Others have made similar suggestions based on their assessment of quality of life among homeless men attending a day shelter (

5). However, no study empirically identified the specific clinical and social adjustment domains that are most strongly related to subjective quality of life among homeless people with severe mental illness.

Using data from more than 4,000 homeless persons with serious mental illness participating in the Center for Mental Health Services' Access to Community Care and Effective Services and Supports (ACCESS) case management program, this study describes the correlates of quality of life at baseline as well as the impact of changes in health and social characteristics on changes in quality of life over a one-year follow-up period.

Methods

In 1994 the Center for Mental Health Services launched the ACCESS program, an 18-site, five-year demonstration program designed to examine the influence of service system integration on the use of services and quality of life of homeless people with serious mental illness (

6). Each site established an intensive case management team to provide comprehensive services for up to one year to a minimum of 100 new consumers each year.

Clients were eligible for ACCESS case management services and for the study if they were homeless, suffered from severe mental illness, and were not involved in ongoing community treatment. Operational entry criteria have been described in detail elsewhere (

7).

Data on demographic, health, and social adjustment characteristics and on clients' subjective quality of life were obtained by independent evaluators at the time of entry into case management and 12 months later. Standardized measures addressed sociodemographic characteristics; substance use; length of time homeless; levels of social support, employment, and income; and overall subjective quality of life (

8,

9,

10).

Overall subjective quality of life was measured using the method employed in the Lehman Quality of Life Interview (

1). The measure consists of an item that asks how the client feels about his or her life overall on a 7-point scale ranging from 1, terrible, to 7, delighted.

Predictor variables used in the analysis included gender (the dummy variable represented male gender); age; race (the two dummy variables represented African American and Latino race); and level of social support as measured by the number of types of people the client could count on for a loan, ride to an appointment, or help with an emotional crisis. Other predictor variables included psychiatric status, which was assessed using self-reported current symptoms of depression (

8) and psychosis (

9) and, at baseline only, interviewers' observation of overtly disturbed behavior (

7).

Level of self-reported substance use was assessed using both the number of days the client drank to intoxication in the previous 30 days and the total number of days of illegal drug use in the past 30 days (

10). Literal homelessness was measured by the number of days the client spent outdoors, in a shelter, or in a public or abandoned building in the past 60 days. Employment, measured as the number of days the client worked in the past 30 days, and total monthly income were also included as predictor variables. The final predictor was service use, measured as the number of six outpatient services—psychiatric, medical, substance abuse, housing, employment, and public support—the client had used during the past 60 days.

Analyses were conducted in several stages. First, repeated-measures analysis of variance was used to determine the extent and direction of change in quality of life from baseline to 12-month follow-up. Next, multiple regression analyses were done to test the significance of relationships between sociodemographic, health status, and social adjustment variables and overall subjective quality of life at baseline.

Finally, we created residual scores for each client by regressing 12-month follow-up measures on the baseline measure of that variable and outputting the residual scores. This procedure created a new set of independent variables that represented the change or improvement in each client characteristic from baseline to 12-month follow-up. We then evaluated the association of these measures of change in clinical and social adjustment status with 12-month measures of quality of life, adjusting for the baseline value of quality of life, to determine which changes in client status had the strongest relationship to improved subjective quality of life at 12 months.

Results

Sample characteristics

During the first three years of program operation, from May 1994 to May 1997, a total of 5,431 clients gave informed consent to participate in the program and completed baseline assessments—an average of 302 clients per site. A total of 4,257 clients, or 78 percent, were successfully followed up at 12 months.

Logistic regression comparing data on 13 baseline measures of sociodemographic, health, and housing characteristics for clients who were successfully interviewed at 12 months with those for clients who were not interviewed showed that they differed significantly on some variables. Clients who were younger, female, or Latino and clients with higher depression and psychosis symptom scores were less likely to be interviewed, whereas African-American clients and those with less social support were more likely to be interviewed. No differences in the likelihood of being interviewed at the 12-month follow-up were associated with interviewers' observations of overtly disturbed behavior or with clients' substance use, housing status, employment status, or income.

The 5,431 clients who gave informed consent to participate in the case management program were a mean±SD of 38.5±9.6 years of age. A total of 62.7 percent were male, 44.5 percent were African American, and 5.5 percent were Latino. All clients received at least one clinical psychiatric diagnosis from a psychiatrist at baseline. In order of frequency, non-mutually-exclusive diagnoses were major depression for 49 percent, schizophrenia for 37 percent, other psychoses for 32 percent, personality disorder for 22 percent, bipolar disorder for 20 percent, and anxiety disorder for 19 percent. Sixty-seven percent of the clients received a diagnosis of a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia, other psychoses, or bipolar disorder.

Substance use disorders were frequently diagnosed; 43 percent of the clients received a diagnosis of alcohol abuse, and 38 percent, drug abuse. Clients drank alcohol to the point of intoxication an average of 2±5.4 days a month and used illegal drugs an average of 3.1±9 days a month.

Changes in quality of life

The clients' rating of subjective quality of life improved by 30 percent, from 3.25±1.7 to 4.23±1.6 over the 12-month period (F=568.4, df=1, 5,429, p<.001).

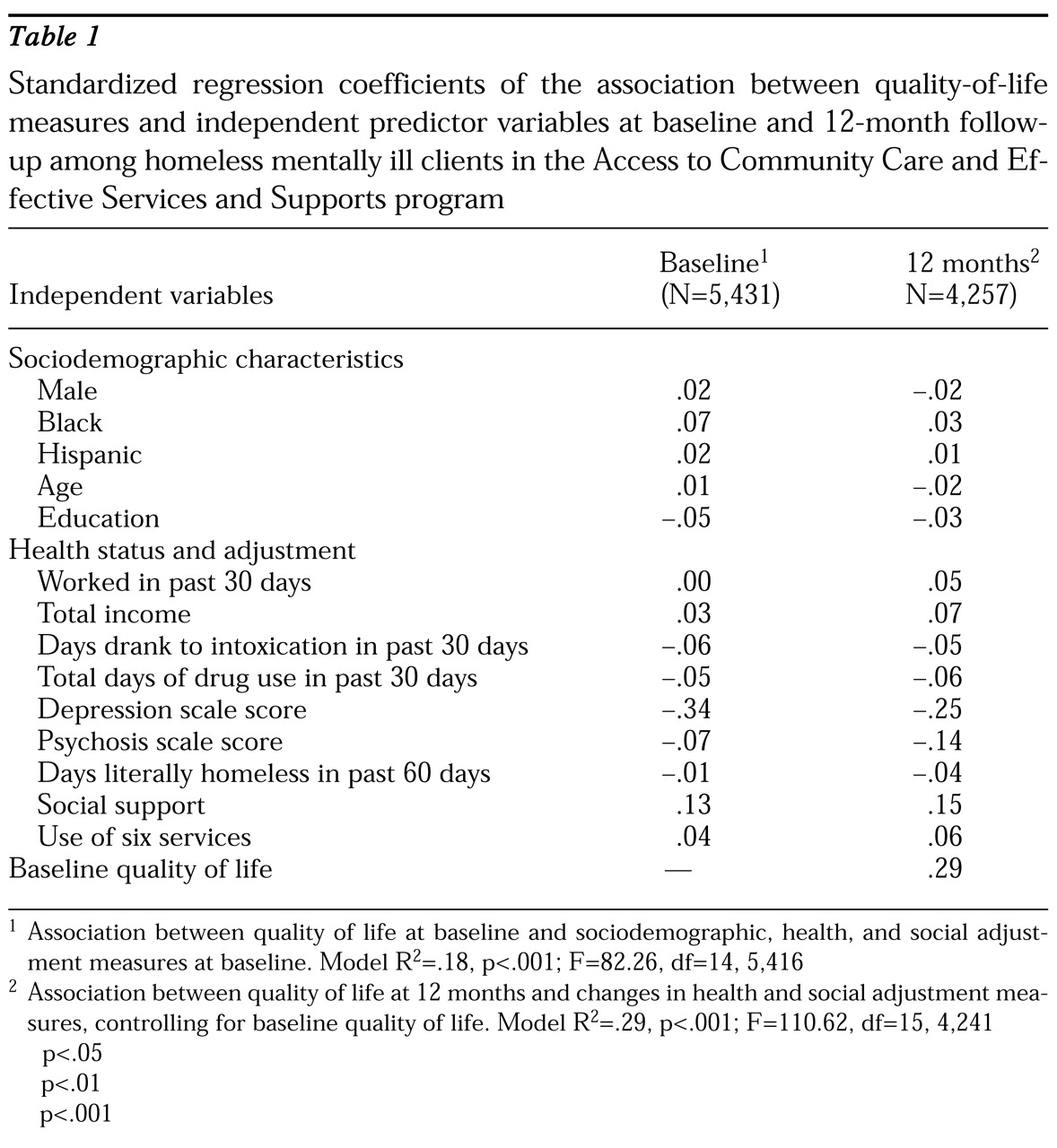

Multivariate analyses examining the associations between baseline client characteristics and baseline quality of life measures are shown in the first data column in

Table 1. Depression had the strongest negative relationship to quality of life, followed by symptoms of psychosis, intoxication, drug use, and years of education. Social support had the strongest positive association with quality of life, followed by being African American, use of services, and income.

The second column in

Table 1 shows the standardized regression coefficients associated with the relationships between changes in client health and social characteristics from baseline to 12-month follow-up and changes in quality of life. In every model we controlled for the sociodemographic variables of gender, race, age, and education as well as the client's baseline level of the quality-of-life indicator being assessed.

These findings parallel the baseline analysis showing that quality of life improved as depression, psychosis, alcohol and drug use, and homelessness declined and as social support, use of services, employment, and income increased.

Discussion and conclusions

Social support and psychiatric symptoms were the most important factors influencing subjective ratings of quality of life at baseline by homeless mentally ill study participants. Self-reported symptoms of mental illness, including depression, psychosis, and substance use, were negatively associated with quality of life at baseline and across time. The extent to which one can depend on others for social support was also positively associated with reported levels of quality of life at baseline and across time.

It is particularly striking that no single dimension of clinical improvement determined quality of life by itself. Rather, factors in each of several domains—including clinical status and social adjustment, as well as sociodemographic characteristics—affected both cross-sectional ratings of quality of life and change.

This study is the first we know of to identify multiple factors that influence quality of life in a large sample of persons who are homeless and have a serious mental illness. The data suggest that focusing treatment on the multiple, independent domains of psychiatric illness, social support networks, work and income, housing, and increased service use is necessary to maximally improve clients' self-assessed quality of life. Future studies should examine whether these factors are similar to those that affect quality of life in other clinical populations and should seek to identify which treatment elements are most effective in bringing about improvement in the multiple domains that ultimately have an impact on quality of life.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded under interagency agreement AM-98C1200A between the Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, and the VA's Northeast Program Evaluation Center. The authors thank local evaluation coordinators Brett Kloos, M.A., Suzanne Golub, M.A., Simeon Goodwin, Ph.D., Jacob Tebes, Ph.D., Mardi Solomon, M.A., Sue Pickett, Ph.D., Greg Meissen, Ph.D., Robert Calsyn, Ph.D., Phyllis White, M.A., Janine Johnson, Cheryl Roberts, M.A., Coleman Poses, M.S.W., Laverne Knezek, Ph.D., Deborah Webb, Ph.D., Marilyn Biggerstaff, D.S.W., and Peter Brissing, M.S.W., for help in data collection and Cindy Cushing, Michele D'Amico, David Dausey, and Jennifer Cahill for help in data processing.