Although previous studies have established an estimated overall lifetime prevalence of bipolar disorder of 1%–3% (

1–

3), the frequency of its diagnosis has been increasing, particularly among youths (

4,

5). Individuals with bipolar disorder have a substantial burden of psychiatric and general medical comorbidity (

6–

10), which in turn predicts baseline illness severity (

11), slower improvement (

12), and an earlier recurrence of new mood episodes (

13,

14).

Elevated frequencies of modifiable risk behaviors, such as cigarette smoking, poor diet, occasional overeating, and lack of exercise, may contribute to the increased prevalence of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and metabolic comorbidities among bipolar disorder patients (

15–

18). Additional behavioral factors in this population, such as increased substance abuse and dependence and lack of adherence to medical regimens, also increase the burden of medical comorbidity (

15,

19,

20). Depression also has direct adverse physiologic impact on heart rate variability and adhesiveness of platelets (

19). Although psychotropic medications are effective at treating the symptoms of bipolar disorder, adverse reactions to these medications might create or precipitate general medical conditions such as hypothyroidism, skin rash, or metabolic disorders (

9,

21–

24).

Persons with bipolar disorder experience relative underrecognition of and inattention to their many physical diseases in mental health settings because nonpsychiatric illnesses are not a main priority (

10) and health care delivery is not configured to adequately detect, diagnose, treat, and manage general medical comorbidity (

6,

10). They are also less likely to utilize general medical services (

25) and are therefore less likely to receive good-quality care for general medical conditions (

15,

24,

26,

27). This in turn results in a more severe course of bipolar disorder (

12), higher likelihood of household maladjustment, impaired functioning at work, receipt of disability payments, reduced employment followed by more frequent medical service utilization (

28), as well as an overall increase in mortality (

27,

29).

Many of the existing studies of comorbidity associated with bipolar disorder targeted specific and more prevalent comorbid conditions and used relatively small samples. We used a large multiyear, nationally representative data set (National Hospital Discharge Survey [NHDS]) to systematically review comorbid conditions in hospital discharge records that noted bipolar disorder. This approach allowed us to detect and evaluate more conditions as well as less prevalent conditions, which might shed light on common etiopathogenic pathways to guide future research insights and to help in allocating needed resources for treatment and prevention.

Methods

Data source

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 1979–2006 multiyear NHDS data were used in the study (

www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhds.htm). A more detailed data source description can be found in a previous publication (

30). The NHDS uses a stratified, multistage probability design and covers discharges from nonfederal short-stay U.S. hospitals. The design enables the generation of national and regional estimates of characteristics of hospitalized patients, length of stay, diagnoses, procedures in hospitals of various sizes, and types of hospital ownership. The data variables used in the study included several demographic characteristics, date of hospitalization, length of stay, source of payment, and up to seven coded diagnoses from the

ICD-9. The

ICD-9 codes are compatible with codes provided in the

DSM-IV-TR, which is used for evaluating and coding psychiatric disorders. Individuals in the NHDS sample could be included more than once if they were hospitalized multiple times during the sampling period and were captured by the sampling methods. For that reason, all estimates reported here refer to discharges and not to individuals. Given the overall low (<1%) probability of data capture during the sampling procedures, the likelihood of a single individual to be represented more than once in the unweighted sample was rather low. There was no danger of unauthorized disclosure and no need for informed consent because NHDS data are publicly available and contain no patient-identifying information. The Walter Reed Army Institute of Research Institutional Review Board approved this study.

Population

All nonchildbirth discharge records for persons alive at the time of discharge and one year of age or older were included (N=5,587,707) for descriptive and time trend analyses. Because our study examined and compared a disease burden in the hospitalized population, the discharge records associated with normal childbirth (ICD-9 code V27) were excluded. Comorbidity was examined only in the discharge records of patients between the ages of 13 and 64 (N=3,073,282), because this age group accounted for more than 85% of the discharges that listed bipolar disorder as a diagnosis. Among the 3,073,282 discharges, a total of 2,352,301 (76.0%) listed more than one diagnosis.

Data coding

Between one and seven diagnoses are listed in each NHDS discharge record; records with at least one diagnosis of bipolar disorder (ICD-9 codes 296.0, 296.1, 296.4–296.7, 296.80, and 296.89) were classified as discharges with bipolar disorder. All other records were considered to be discharges without bipolar disorder. If more than one ICD-9 discharge diagnosis was listed, the record was considered to include a comorbid condition, presented in this report as a three-digit ICD-9 code. For the comorbidity analyses, only discharges with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder (N=27,054) in the primary position were defined as cases; records that had bipolar disorder codes in any other position were excluded from these analyses. The proportions of comorbid conditions in this group were compared with the proportions in the group with any other primary diagnosis (N=2,325,247).

Statistical analyses

The NHDS weighting variable was used to provide national estimates (weighted frequencies) for demographic characteristics, region, source of payment, and length of stay for hospital discharges. We calculated proportions (percentages) of discharge records with bipolar disorder among all hospital discharges and compared them by demographic groups. Ratios with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusted for sex, age, race, region, and year, were used as measures of comparison and significance.

Using previously reported statistical approaches (

30), we analyzed frequencies of comorbid conditions for discharges with bipolar disorder as the primary diagnosis and for those with any other primary diagnosis. We present only unweighted analyses to show the proportions of concurrent conditions and their associations with primary diagnosis because the NHDS weighting variable was not designed to provide national estimates of the co-occurrence of diagnoses. Results of weighted and unweighted analyses were essentially the same. In order to examine the prevalence of disorders among discharges with and without a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder, we counted and sorted by frequencies all concurrent conditions and calculated proportional morbidity. The proportional morbidity ratios (PMRs) were calculated and presented for the most prevalent comorbid conditions in discharges noting a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Because multiple comorbid conditions were listed in some records, a cumulative prevalence (or count) of conditions was higher than the count of records.

Results

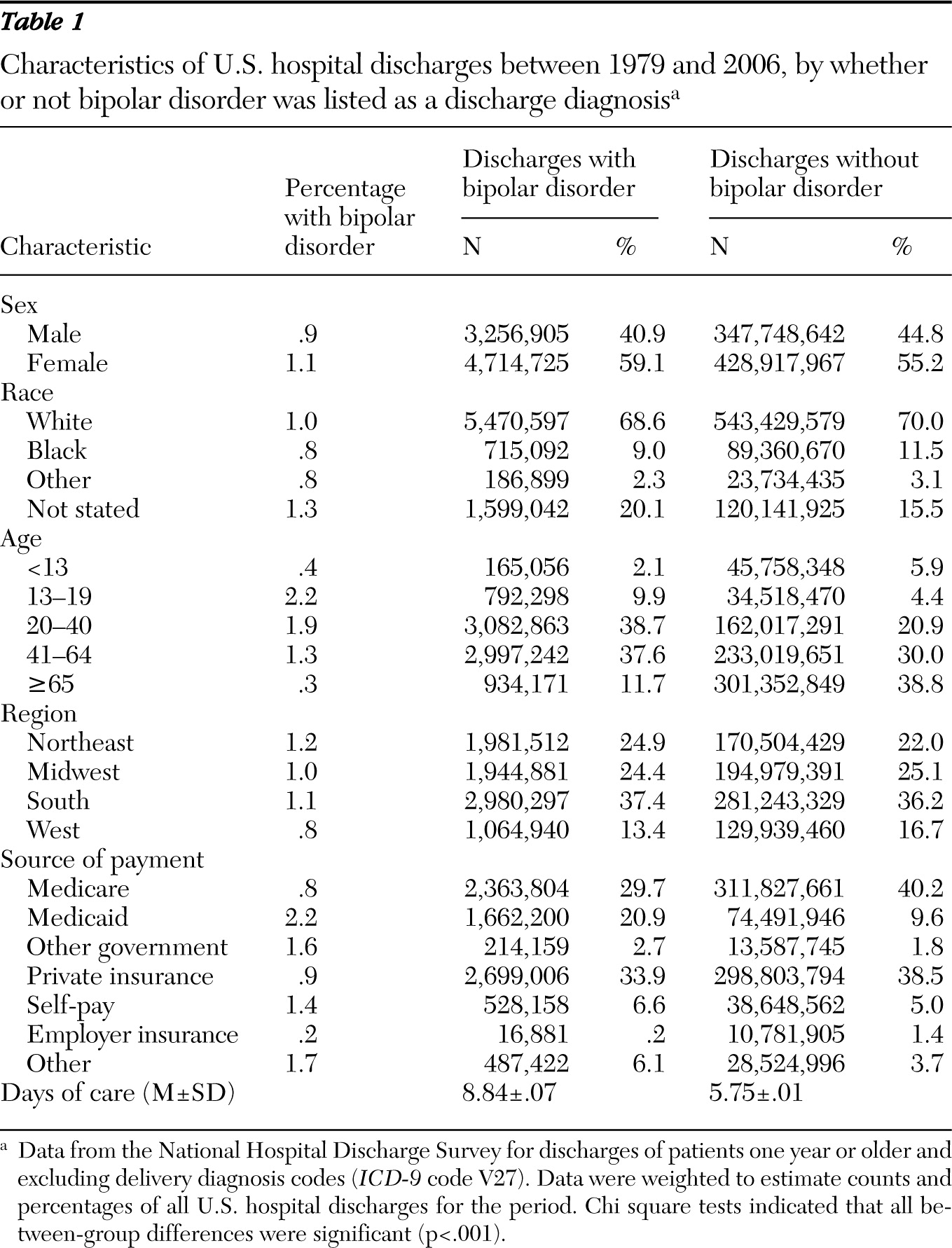

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics from the discharge records of patients with and without a diagnosis of bipolar disorder, weighted to reflect all U.S. hospital discharges. The overall proportion of discharges with bipolar disorder was 1.0%, and the proportion varied significantly (p<.001) by demographic group. Females had a higher proportion of discharges (1.1%) than males (.9%). The proportion of discharges with bipolar disorder among whites (1.0%) was higher than the proportion of discharges with bipolar disorder among blacks (.8%) or persons of other races (.8%). The proportion of discharges with bipolar disorder was highest among adolescents ages 13–19 (2.2%) and decreased in older age groups: 1.9% for ages 20–40 and 1.3% for ages 41–64. Proportions of discharges with bipolar disorder were highest among discharges in the Northeast region (1.2%) and lowest among discharges in the West (.8%). Proportions of discharges with bipolar disorder varied greatly depending on the source of payment for the hospitalization, with Medicaid (2.2%) being the highest and an employer insurance program (.2%) the lowest.

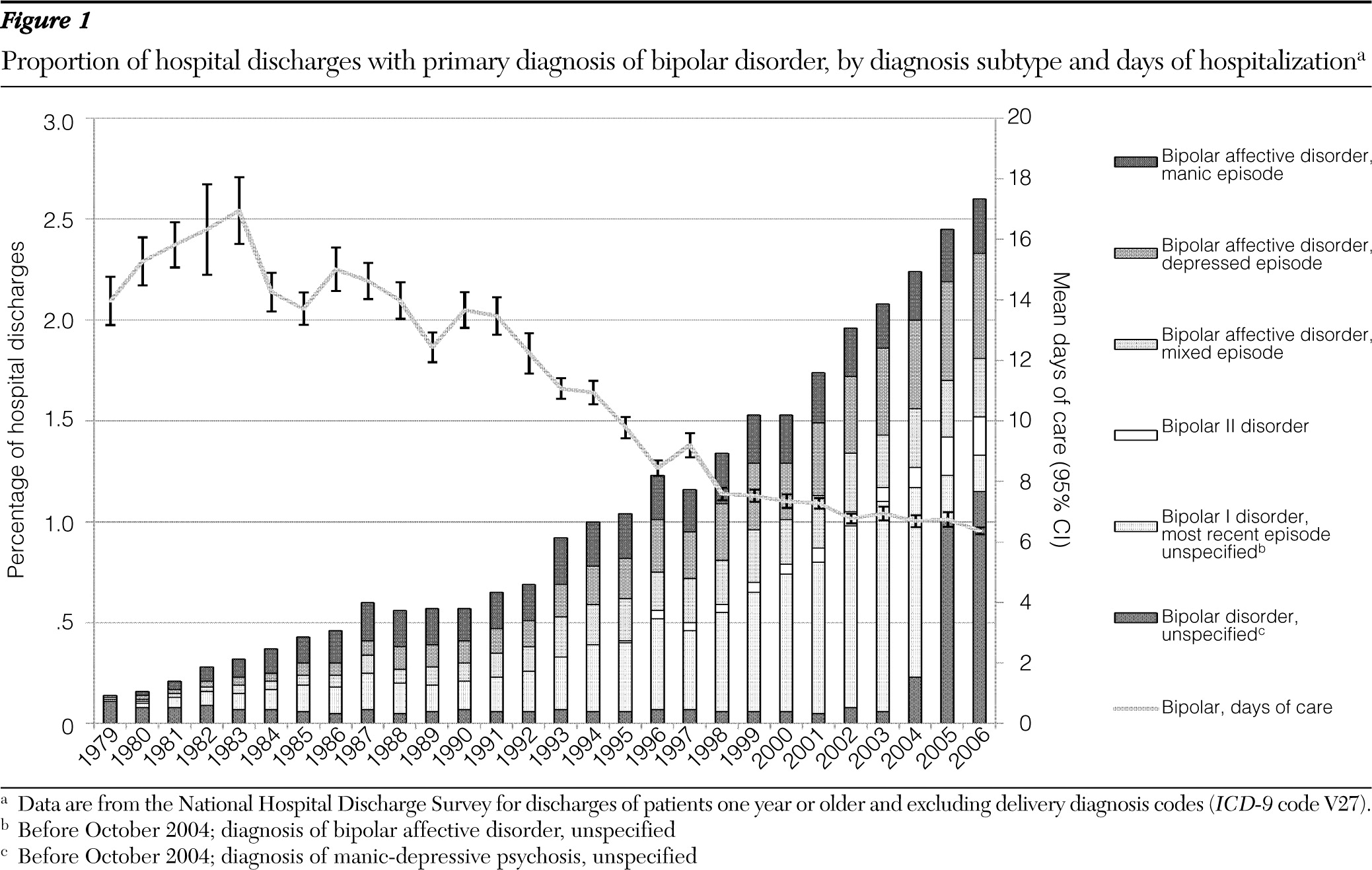

The proportion of hospital discharges with bipolar disorder increased more than tenfold over the study period, from .24% in 1979 to 2.6% in 2006 (

Figure 1). The proportional distribution of the diagnostic subtypes remained relatively constant over the study period, but the patterns varied as a result of the changes noted below. The frequency of type II bipolar disorder increased substantially since its initial description and inclusion as a diagnostic subtype in

DSM-IV in 1994. Another substantial change came in 2004 when the wording of several

ICD-9 codes changed (

31,

32). There were no significant differences between males and females in the distribution of bipolar disorder diagnostic categories over the time period (data not shown).

The mean length of hospital stay for discharges with any diagnosis of bipolar disorder over the study period was 8.8 days, compared with 5.7 days for discharges without bipolar disorder (p<.001;

Table 1). The mean length of hospital stay for all discharges with bipolar disorder decreased (from 14.0 days in 1979 to 6.4 days in 2006; p<.001;

Figure 1), as did the length of stay among discharges without bipolar disorder (from seven days in 1979 to 4.6 days in 2006, p<.001; data not shown).

Of the 57,788 nonweighted discharges with a listing of bipolar disorder, 36,279 (62.8%) discharges listed bipolar disorder as the primary diagnosis, and 27,054 (74.6%) of those had at least one comorbid condition.

The 15 most prevalent conditions are listed in

Table 2. Psychiatric and behavior-related diagnoses accounted for 47% of the comorbid diagnostic categories among discharges with bipolar disorder, compared with 20% among discharges with a different primary diagnosis.

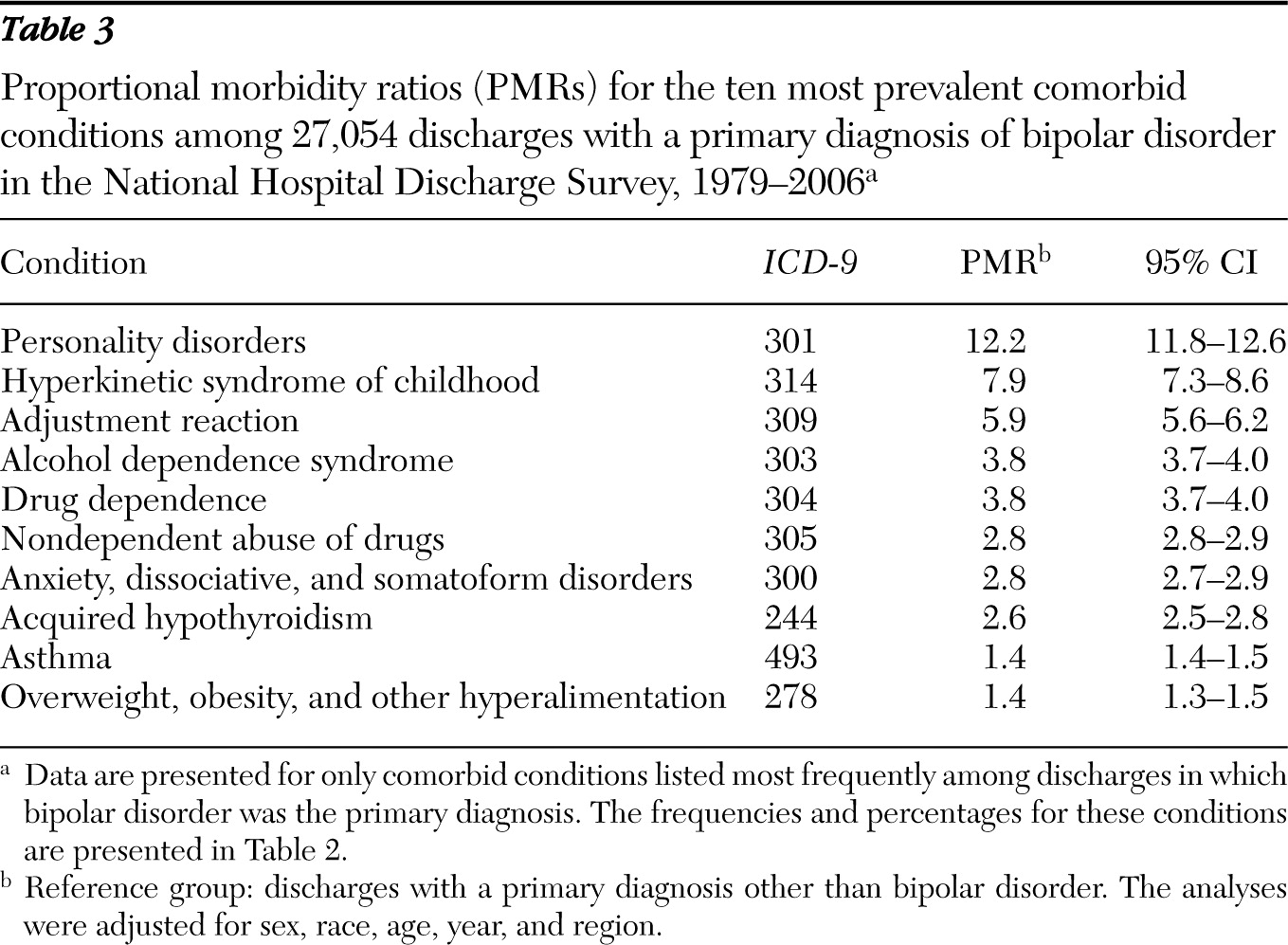

The proportional morbidity ratio for each of the ten most common conditions that were more prevalent among discharges with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder compared with those without bipolar disorder are presented in

Table 3. The first seven conditions are psychiatric or behavior-related diagnoses. Other prevalent nonpsychiatric conditions that were found to be significantly more prevalent among discharges with bipolar disorder were acquired hypothyroidism (proportional morbidity ratio=2.6), asthma (proportional morbidity ratio=1.4), and overweight, obesity, and other hyperalimentation (proportional morbidity ratio=1.4).

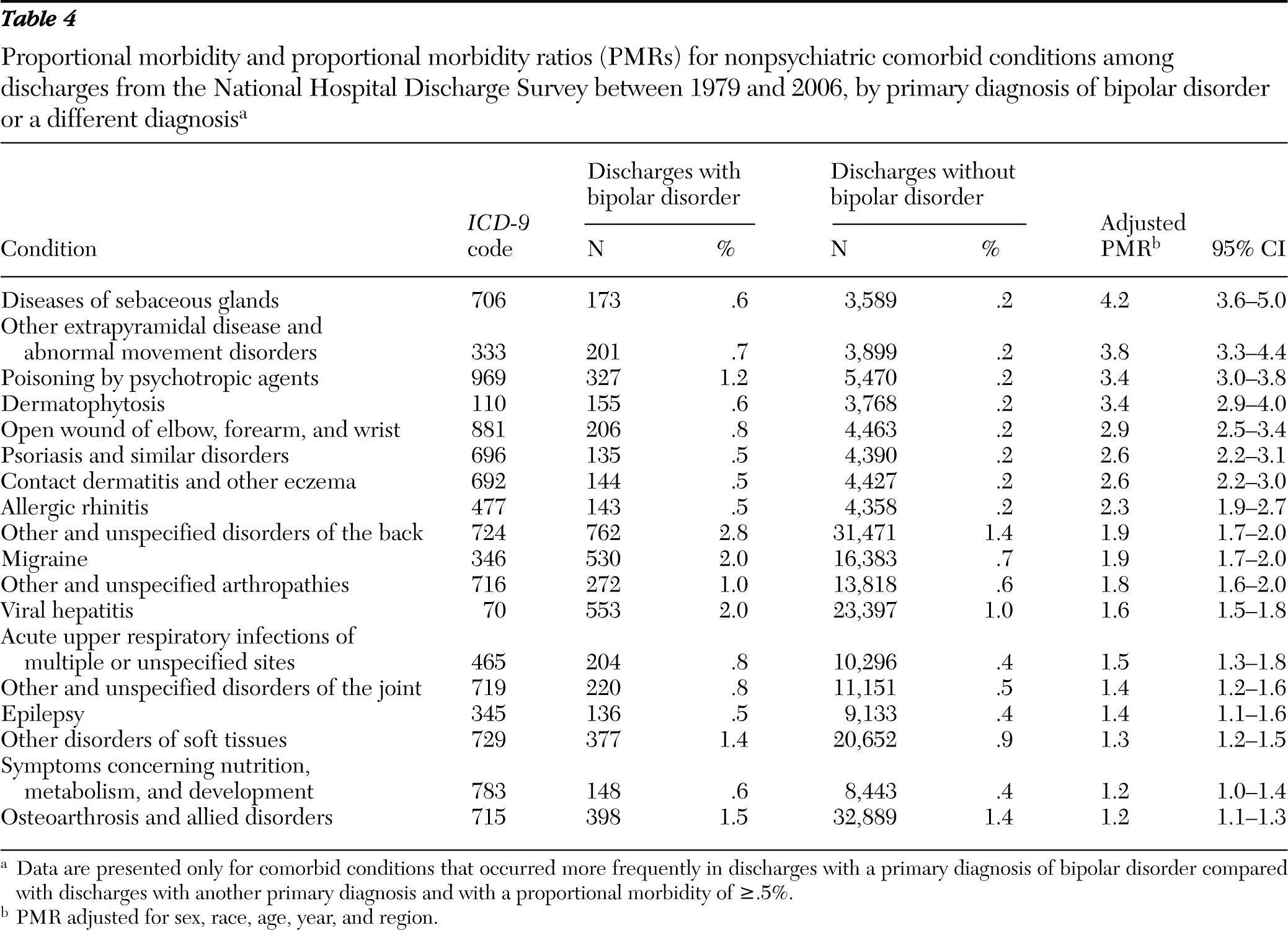

Table 4 shows proportional morbidity ratios for every nonpsychiatric comorbid condition that was more prevalent among the discharges with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder compared with discharges with a different primary diagnosis and with a proportional morbidity of at least .5%. These included certain diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (proportional morbidity ratio range 2.6–4.2), and nervous (range 1.4–3.8), respiratory (range 1.5–2.3), and musculoskeletal (range 1.2–1.9) systems.

Discussion

Our study is the first to examine both psychiatric and general medical comorbidity in a survey representative of all bipolar disorder hospital discharges in the United States. Understanding the most prevalent comorbid conditions in this population is all the more necessary when the prevalence of hospitalizations due to bipolar disorder continues to increase. Although the dramatic increase in diagnosis of bipolar disorder has been previously noted in the NHDS and other populations, reasons for the heightened proportion are not entirely clear. Such an increase may be due to improved recognition of bipolar disorder over the past 20 years (

33–

36), better insurance coverage for major mental illnesses, decreased stigma (

37), or even a recent tendency toward overdiagnosis (

38,

39). Despite the increase in almost all bipolar disorder subtypes, the proportion of hospitalizations with a current manic episode has remained relatively stable since 1987. This discordance may be at least partially explained if hospitals have become more adept at recording patients' past history. Although anamnestic information is unnecessary for the diagnosis of a current manic episode, it is essential for establishing any other subtypes of bipolar disorder.

In our population of hospitalized patients, a decrease in the length of stay may also have led to an increase in readmission, which we believe to be rare overall. Describing the demographic characteristics of the bipolar disorder population is also a necessary component to understanding prevalent comorbid conditions. And even though differences in populations studied and definitions of bipolar disorder make comparisons between studies challenging, our results parallel studies that have found the proportion of those with bipolar disorder to be higher among females (

2,

6,

40), whites (

2,

40), and those 13–40 years old (

2).

The high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric conditions, such as personality disorders and adjustment disorders, among discharges with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder is in accordance with the multiaxial assessment system. As noted in

DSM-IV-TR, the multiaxial system is used for psychiatric assessments to facilitate comprehensive and systematic evaluation with attention to various mental disorders and relevant general medical conditions. Use of the multiaxial system could explain the much higher prevalence of psychiatric conditions among discharges with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder. We also found close to a fourfold increase in the proportion of alcohol and drug dependence and a threefold increase in drug abuse comorbidity among bipolar disorder discharges versus discharges without bipolar disorder, a finding supported by other studies (

41,

42). The higher prevalence of substance use disorders may reflect bipolar patients' attempt at self-medication (

43), or perhaps substance abuse may precipitate affective symptoms among persons who otherwise would not develop an affective illness (

44). Unfortunately, the increased abuse of drugs and alcohol most likely worsens the level of comorbidity of general medical conditions as well.

We found many general medical conditions that were elevated in hospital discharges with a primary diagnosis of bipolar disorder. Even so, it is likely that the true prevalence of comorbid general medical conditions was underestimated among those with bipolar disorder, because the primary reason for hospitalization was likely focused on diagnostic determination and treatment of psychiatric conditions. In addition, hospital psychiatrists are pressed to keep length of stay short and may not be reimbursed for any medical workups during a patient's stay on a psychiatric unit. Bipolar disorder patients, therefore, may not have been screened for non-life-threatening nonpsychiatric comorbid conditions. This could be the reason why some conditions have been repeatedly reported to be associated with bipolar disorder in previous studies (

6,

8,

26) but were not increased in our population.

There are a number of possible reasons for the increased level of general medical comorbidity among bipolar disorder patients. As mentioned previously, bipolar disorder patients have a variety of risk factors, such as poor dietary health, smoking, substance abuse, decreased access to care, or increased risk taking, which can contribute to the higher burden of comorbidity. Recently, there has also been a movement to understand the chronic stress response via allostatic load among bipolar disorder patients and its role in contributing to increased comorbidity. There is evidence that many bipolar disorder patients exhibit dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, altered immunity, and proinflammatory and oxidative stress states, leading patients to become more vulnerable to environmental stressors, future bipolar episodes, drugs of abuse, organ damage, and subsequent increase in general medical comorbidity (

45,

46). Certain neurological disorders may have a more direct connection to the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder.

We found an increased proportion of bipolar disorder patients with comorbid migraine and epilepsy, disorders known to be caused by biochemical alterations in the brain and found to be associated with bipolar disorder (

47,

48). Although the relationships between the disorders remain complex and not well understood, the fact that a number of anticonvulsants have been used successfully with all three disorders may provide evidence for etiopathogenic similarities between the disorders (

49). In addition, conditions such as hypothyroidism, obesity, and various skin conditions are all acknowledged side effects of several of the medications used for treating bipolar disorder, which may explain a portion of their elevated associations, although factors inherent to bipolar disorder itself could also contribute to the increased proportions (

50).

There are several notable strengths of our study. We used a large, nationally representative database that has been underused in previous psychiatric research. In addition, this multiyear data set produced by the CDC has standardized variables across years to decrease year-to-year variability. Thus we were able to compare diagnostic trends over a 28-year time frame. Furthermore, the proportional morbidity ratios were adjusted by age, sex, race, geographic region, and hospitalization year to ensure more accurate and robust comparisons.

Our study also had a few limitations to report that may warrant further investigation. First of all, the study examined hospitalizations, not patients; a patient could be represented more than once. If the rehospitalization of patients with bipolar disorder was higher or lower than those with other conditions, the proportion of discharges with bipolar disorder was probably accordingly over- or underestimated. However, because the probability that the same person would be represented more than once in the unweighted data set was low, any such bias would be unlikely to considerably change our results or conclusions. Proportional morbidity ratios could also be biased if a condition increased or decreased the likelihood of hospitalization when comorbid with bipolar disorder but not with any other disorder. The NHDS data are cross-sectional, so no directionality can be attributed to the association between conditions nor can any association be suggestive of a causal relationship. All the diagnoses were based on administrative data, and we did not have structured interviews to confirm their accuracy.