Suicide is the third leading cause of death among youths ages ten to 24. Reducing both suicide and suicide attempts are national health promotion goals (

1). The National Strategy for Suicide Prevention identifies the emergency department as an important suicide prevention site and includes as a national objective increasing rates of mental health follow-up treatment for suicidal patients who are discharged from emergency departments (

2). Youths presenting with suicidality to emergency departments are a high-risk group: medically dangerous suicide attempts are treated in emergency departments, and a prior suicide attempt is a strong predictor of future attempts, death by suicide, and other negative outcomes (

3). Yet, many of these youths do not receive outpatient mental health treatment despite evidence that such treatment may improve outcomes (

4).

This article presents results of a randomized controlled trial (RCT) that evaluated the Family Intervention for Suicide Prevention (FISP) in comparison with usual emergency department care that was enhanced by staff training. The FISP is an adaptation of the specialized emergency room intervention listed as a promising practice in the

Registry of Evidence-Based Suicide Prevention Programs (

5) and uses the emergency department visit as a window of opportunity to deliver an effective intervention and link youths to outpatient mental health treatment. A pilot quasi-experimental trial suggested that when combined with a structured outpatient cognitive-behavioral family treatment, the emergency department intervention led to improved adherence to outpatient treatment, less suicidal ideation, and less depression (

4,

6). In the pilot, patients from one time period were assigned to usual emergency department care, and patients from another time period were assigned to the intervention. Hence, results could reflect differences in the two time periods rather than (or in addition to) intervention effects. The RCT reported here overcame this difficulty, allowed evaluation of the emergency department intervention independent of the effects of the outpatient treatment, adapted the emergency department intervention to “usual” emergency departments where access to outpatient treatment is not guaranteed (

7), and evaluated the intervention in two emergency departments that differ from the original emergency department development site (Columbia Presbyterian Hospital, New York).

This is the first RCT to evaluate the FISP emergency department intervention independently of outpatient cognitive-behavioral family treatment, and to our knowledge it is the largest completed RCT for evaluating an emergency department intervention specifically for pediatric suicidal patients (

8). We predicted that the FISP, relative to enhanced usual emergency department care, would be associated with higher rates of outpatient treatment, particularly psychotherapy (the FISP treatment modality). The secondary outcome was fewer suicide attempts. We also explored intervention effects on youths' suicidal ideation, depression, other mental health and functioning problems, parent depression, and family functioning.

Methods

Setting and design

Patients were recruited from two emergency departments in Los Angeles that were selected to include different geographic areas and populations. Emergency department A is in a largely middle-class area, connected to a psychiatric hospital with youth inpatient services, and serves roughly 42,000 patients annually. Emergency department B is operated by the Los Angeles County Department of Health and serves roughly 77,000 public-sector patients annually across psychiatric, adult, and pediatric emergency departments. All procedures were approved by the site institutional review boards; all participants gave informed consent or assent to participate. This report focuses on follow-up procedures; detailed descriptions of the baseline sample and methods are provided elsewhere (

7,

9).

Consecutive patients (N=181) were recruited between April 2003 and August 2005. Emergency department personnel identified possible participants and paged study staff, who verified eligibility and enrolled participants. The earlier pilot included only female adolescent attempters; therefore, to meet the needs of emergency departments to treat the diverse youths presenting with suicidality, we expanded eligibility criteria to include both females and males ages ten through 18 who presented with suicide attempts or ideation. Inclusion criteria for this RCT were presenting to the emergency department for suicide attempts, ideation, or both and ages ten to 18. Exclusion criteria were having acute psychosis or symptoms that impede consent and assessment, having no parent or guardian to provide consent, youth not speaking English, and parents or guardians not speaking English or Spanish.

After the 181 participants completed the 20- to 30-minute baseline assessment, they were randomly assigned to either the FISP intervention (N=89) or to usual care (N=92). Randomization was stratified by site, and assignments were made by a computerized random number generator and completed through project directors who accessed the computerized system. When patients were randomly assigned to the FISP intervention, clinicians were called or paged to deliver the intervention in the emergency department. Recruitment and assessment staff were blinded to randomization status. Follow-up assessments were completed at about two months after discharge from the emergency department or hospital (median=41 days, mean±SD=57±51 days). Measures were available in Spanish and English for parents.

RCT condition

Control.

Usual care was enhanced by a training session for emergency department staff. Based on practice parameters developed by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Practice (

10), the training emphasized the importance of linking suicidal patients to outpatient mental health treatment, restricting their access to dangerous or lethal attempt methods, and the increased risk associated with substance use. Training was conducted during staff meetings and supplemented by informal contacts and distribution of a handout on practice parameters (

7). A list of referral resources was available at each emergency department.

FISP.

The FISP intervention began with a brief youth and family crisis therapy session in the emergency department that focused on the following: reframing the suicide attempt as a problem requiring action, educating families about the importance of outpatient mental health treatment and restricting access to dangerous attempt methods, and obtaining a commitment from the youth to use a safety plan in future crises; strengthening family support by encouraging youths and parents to identify positive attributes of the youth and family; developing a hierarchy of potential suicidality triggers by using an “emotional thermometer” to identify feelings and physical, cognitive, and behavioral reactions to these triggers; developing and practice using a safety plan for reducing “emotional temperature” and risk of increasing suicidality; and creating a safety plan card to provide a concrete tool that youths could use at times of acute stress and suicide risk to cue reminders of reasons for living and safe and adaptive coping. This was often supplemented by suggesting that youths develop a “hope box,” which expanded on the safety plan card with concrete objects to cue use of the coping strategies listed on the card (for example, CDs or play lists of calming music, scented bubble bath, and coping cards) (

7,

11,

12).

Structured telephone contacts for motivating and supporting outpatient treatment attendance were made within the first 48 hours after discharge from the emergency department or hospital, with additional contacts as needed (usually at one, two, and four weeks postdischarge). These were modeled after other compliance enhancement and care manager interventions (

13,

14).

Clinicians with graduate mental health training received didactic training with role playing, observed intervention sessions, and were observed until a senior clinician certified them as proficient. Throughout the study, clinicians received regular quality assurance monitoring and supervision. Additional details are provided in our clinical article (

7).

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was linkage to outpatient mental health treatment, which was assessed with our modified version of the Service Assessment for Children and Adolescents (

14), adapted for the emergency department population. Reliability of parent and youth reports was strong for measures of presence or absence of outpatient mental health treatment, psychotherapy, and medication (

κ=.72–.93). Because parents are generally more reliable reporters than children of more objective variables (

15), we used parent reports, substituting youths' data when parents' data were unavailable. Results of sensitivity analyses using youth report as the primary source were similar.

The secondary outcome was suicide attempts assessed with the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children Version IV (DISC-IV), an established psychometrically strong diagnostic interview (

16,

17). Because youths are considered to be more sensitive and accurate reporters than their parents on variables that assess the youth's internal state, such as suicidal intent and depression (

15), we used youths' reports, substituting parents' reports when youths' data were unavailable. Sensitivity analyses of parents' reports led to the same conclusions. Youths' reports on the Harkavy Asnis Suicide Scale (HASS) (

16) provided additional details on level of suicidality during the follow-up interval (

α=.89–.92). The HASS includes two subscales: active suicidal behavior and ideation (five items, for example, “tried to kill yourself”) and more passive suicidal ideation (12 items, for example, “had ideas about killing yourself”).

Other exploratory outcomes were youth and parent depression, assessed with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D), a self-report measure of past-week symptoms that has well-established psychometric properties for adolescents and adults (

18,

19). The parent-completed Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) provided a measure of overall psychopathology (total problems, externalizing behavioral problems, and internalizing emotional problems) (

20). Family functioning was assessed by youth report on the Conflict Behavior Questionnaire (CBQ) (

21).

Statistical analysis

To assess balance across RCT arms, we used standard univariate statistics to compare FISP and control groups on demographic and baseline clinical characteristics, time to follow-up, and follow-up completion rates. Intervention effects were evaluated with intent-to-treat analyses for each outcome, regardless of the level of intervention received. We fitted logistic regression models for dichotomous outcomes and linear regression models for continuous outcomes, with intervention status as the main independent variable. In all analyses, we adjusted for baseline score for the same outcome, days between baseline and follow-up, site, age, gender, CBCL total problems (because of marginally higher scores in the FISP group versus the control group (p<.10), and CES-D (because follow-up participation rates varied significantly by baseline scores; t=2.3, df=179, p=.02). For highly skewed count variables, negative binomial regression was used. To show effect sizes, we present unadjusted means and proportions by intervention condition and adjusted mean differences for continuously scaled variables, odds ratios (ORs) for binary variables, and rate ratios (RRs) for count variables that were adjusted for the covariates listed above. We conducted sensitivity analyses that limited the time from baseline to follow-up to 90 days (N=135); other analyses adjusted for length of hospitalization and pre-emergency department treatment status, with no change in conclusions or substantive results. We used multiple imputation to address missing data for the 12% of patients who did not complete follow-up assessments (MI procedure in SAS version 9.2) (

22,

23).

To examine time effects on clinical outcomes, we fitted mixed-effect regression models for continuously scaled variables using the SAS MIXED procedure, and we fitted the mixed-effect logistic regression model for dichotomous variables using the SAS GLIMMIX procedure with time indicator (baseline or follow-up) as the primary predictor and with controls for intervention status, study site, age, and gender. We specified a random intercept model to account for the within-subject correlation over time.

Because of the multiple comparisons for this analysis, we used a conservative p value of <.01 to detect statistically significant differences. The study was designed to have a power of .80 with an alpha of .05 (two-sided) to detect ORs of 2.5 or higher in rates of treatment linkage and 4.5 in suicide attempt rates. Enrolling 90 patients per condition allowed an attrition rate of up to 15%.

Results

Among 340 youths approached about the study, 254 were eligible (75%) and 86 were ineligible (48 parents not present to provide consent or participate, ten were not English or Spanish speakers, and 28 met other exclusion criteria); 210 of the 254 eligible youths (83%) completed baseline assessments, 29 were excluded after baseline (27 were from the pilot phase and were not included in the randomization, and two were determined ineligible after baseline), and 181 were enrolled in the RCT. [A figure showing the flow of participants in the intervention trial is included as an online supplement to this article at

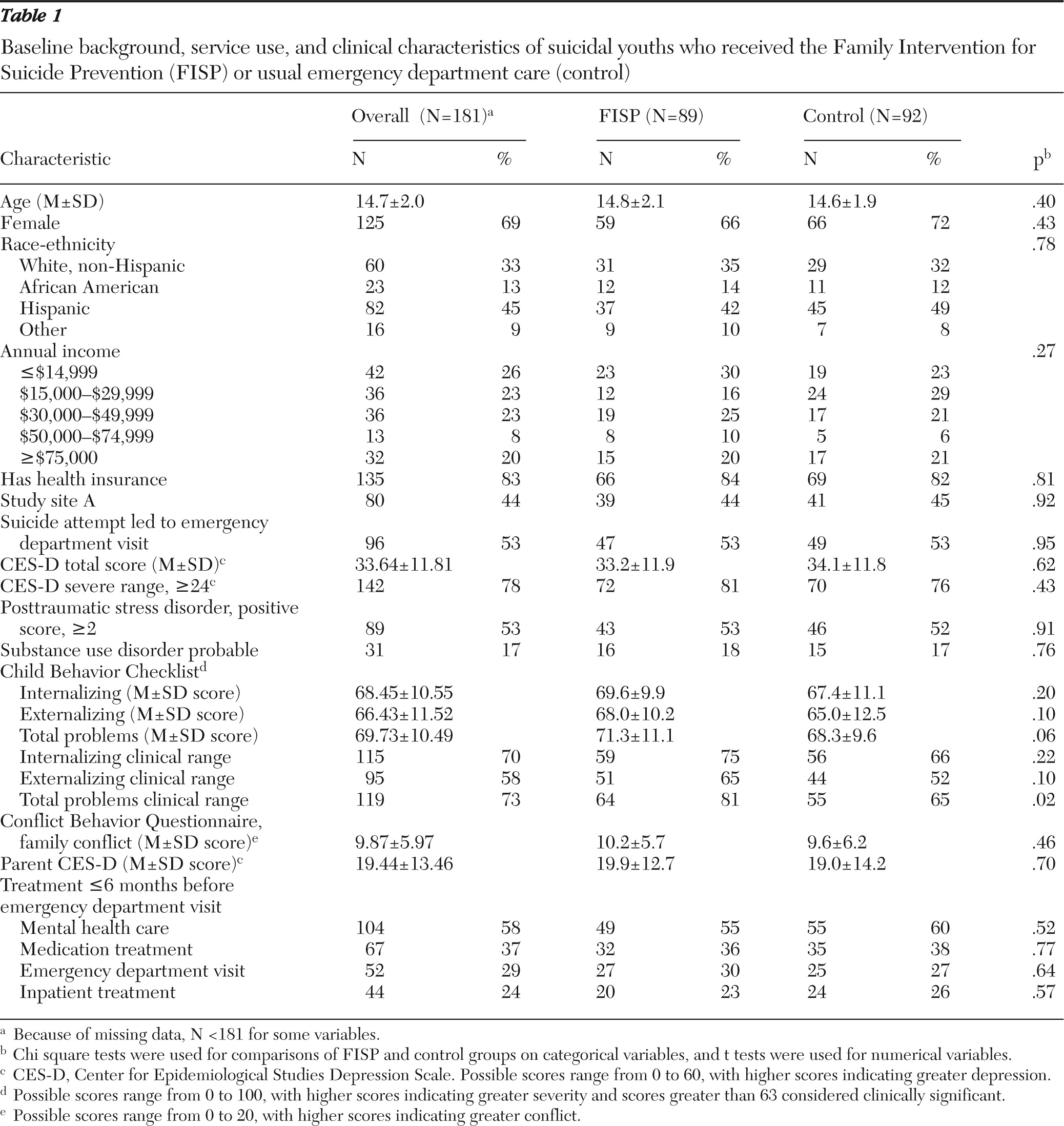

ps.psychiatryonline.org.] Patients' mean age was 14.7±2.0, 69% were female, and 67% were from racial-ethnic minority groups (

Table 1). The emergency department visit was due to a suicide attempt by 53% of the youths, with the remainder due to suicidal ideation. Past-year suicide attempts were reported by 66% (N=120) of the youths, with 27% (N=49) reporting multiple (two or more) past-year attempts. Mental health and functioning problems were common at baseline: 78% reported severe depression (CES-D ≥24); 53% screened positive for posttraumatic stress disorder (

24); 17% reported probable substance abuse (

25); and 70%, 58%, and 73% of youths scored in the clinical range on the CBCL internalizing, externalizing, and total problems subscales, respectively (

20). FISP and control groups were similar at baseline, with the exception of higher total problem and externlizing scores in the FISP condition.

Most youths were hospitalized after emergency department evaluation and treatment (70%, N=124 of 177), with no significant between-group differences. On the basis of retrospective assessments completed at follow-up, 40% (N=56 of 139) of youths met DISC-IV criteria for depressive disorders in the year before the emergency department visit (53 with major depression and three with dysthymic disorder), with no significant group differences. Youths not meeting criteria for depressive disorders still had high levels of depressive symptoms (71%, or N=59 of 83, with a CES-D score ≥24) and externalizing problems (54%, or N=42 of 78, in the clinical range) and internalizing problems (65%, or N=51 of 78, in the clinical range).

Linkage to outpatient community mental health treatment

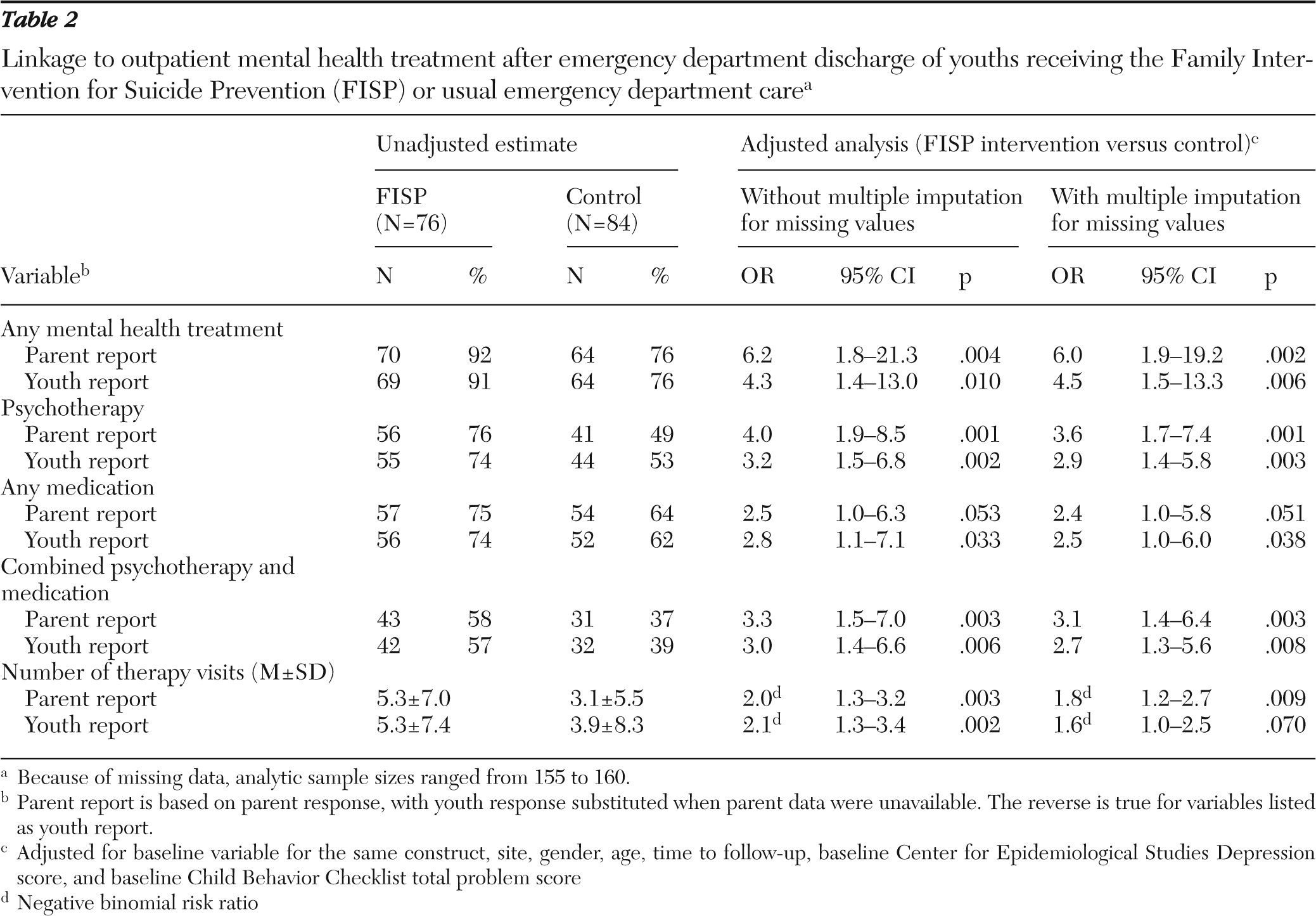

Table 2 shows the intervention effect on linkage to outpatient treatment, with and without multiple imputation for missing values. FISP patients were significantly more likely than those in the control group to be linked to outpatient treatment (92% versus 76%; OR=6.2, p=.004). FISP patients also had significantly higher rates of psychotherapy (76% versus 49%; OR=4.0, p=.001), combined psychotherapy and medication versus monotherapy (psychotherapy or medication alone) or no treatment (58% versus 37%; OR=3.3, p=.003), and significantly more outpatient treatment visits (FISP group, mean=5.3, median=3.0, range=0–36; control group, mean=3.1, median=.5, range=0–28).

Inpatient hospitalization was also associated with increased linkage (91% versus 67%, χ2=14.69, df=1, p=.001). However, the intervention effect remained significant when hospitalization was included in the model (χ2=8.37, df=1, p<.004) and when the sample was restricted to hospitalized patients (97% FISP versus 86% control, difference=11%, χ2=4.18, df=1, p<.05, N=114). Within the smaller sample of 45 nonhospitalized youths, the between-group difference was larger but marginal (82% FISP, 57% control; a difference of 25%).

Suicidality and exploratory outcomes

At follow-up, nine youths had attempted suicide (6%), four who received the FISP intervention (6%) and five who received enhanced usual emergency care (6%). There was one completed suicide. Suicidal ideation was observed among 18 youths (eight in FISP, 13%; ten in the control group, 13%) on the DISC-IV. There were no statistically significant intervention effects on suicidality or other clinical or functioning outcomes. [Summaries of suicide attempt and outcomes are presented in two tables in the online supplement at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Results from random effects models revealed statistically significant improvements from baseline to follow-up (CES-D total score, t=−8.5, df=130, p<.001; severe depression on CES-D, OR=.24, 95% confidence interval [CI]=.14–.41, p<.001; CBCL total problems in clinical range, OR=.52, CI=.30–.90, p=.02; parent CES-D, t=−2.15, df=96, p=.04; and CBQ, t=−10.12, df=128, p<.001).

Did outpatient treatment linkage affect clinical outcomes?

Given the significant intervention effect on linkage to outpatient treatment and nonsignificant effects on clinical outcomes, we conducted exploratory instrumental variables analyses to examine whether linkage was associated with improved clinical outcomes. These analyses were used to estimate the effect of linkage and adjust for selection effects that with traditional analyses could lead to nonsignificant treatment outcome relationships (

26–

28). Instrumental variables analyses rely on identification of an instrument that predicts the probability of treatment but has no independent effect on outcomes. We used randomized intervention status as the instrument andlinkage to any outpatient mental health treatment and then examined three youth outcomes: suicidal behavior (HASS suicidal behavior), severe depression (CES-D score ≥24), and overall psychopathology (CBCL total problems, clinical range). For the HASS score, we fit two step treatment effects models, using the treatreg command in Stata version 11.1. For two binary outcomes, we fit a bivariate probit regression model with the biprobit command to jointly model clinical outcome and treatment linkage, explicitly taking into account the correlation. In all models, the effect of intervention on linkage was significant (p <.05), but no statistically significant benefits of treatment linkage on clinical or functioning outcomes (HASS, CES-D, and CBCL total problems) emerged, and treatment linkage was associated with more severe depression assessed on the CES-D. [A table in the online supplement reports results of the instrumental variables analyses.]

Discussion

The FISP intervention was associated with improved linkage to outpatient mental health treatment, relative to usual emergency department care, a finding that indicates that the FISP offers one strategy for addressing our National Suicide Prevention Objective of increasing linkage to outpatient mental health treatment for suicidal youths who were treated in the emergency department (

2). Clinically, 6.3 youths would need to receive the FISP intervention in order to prevent one youth from failing to receive outpatient treatment. Given the high morbidity and mortality of these patients, this is a clinically meaningful finding that emerged in the presence of high hospitalization rates from the emergency department.

Despite the success of the FISP in improving our primary outcome (treatment linkage), the intervention did not lead to significant decreases in suicide attempts or improvements on other clinical or functioning outcomes. Although a brief emergency department intervention could lead to some direct clinical benefits, we expected that most clinical benefits from the intervention would result from improved linkage to outpatient mental health treatment. However, exploratory instrumental variables analyses suggested that treatment linkage, although necessary for delivering effective treatment, did not lead to improved clinical or functioning outcomes. These results are consistent with data indicating poor outcomes for usual mental health treatment for youths (

29) and with a recent British study indicating that a brief therapeutic assessment led to improved outpatient treatment linkage but no benefits on clinical outcomes (

30). Together, these findings suggest that brief emergency department interventions require supplementation by efforts to improve typical outpatient treatment. There was a tendency toward improvement over time. Still, during the follow-up period, one youth died by suicide, 6% made attempts, 18% reported some active suicidal behavior on the HASS, over 50% reported severe depression, and 63% scored in the clinical range for total problems.

The impact on clinical outcomes observed in the pilot evaluation of the initial emergency department intervention plus outpatient cognitive-behavioral family treatment (

4) suggests that this outpatient treatment may have strengthened the clinical benefits of the emergency department intervention. Although we currently lack treatments with clear evidence documenting efficacy for reducing suicide attempt rates by adolescents, a number of treatments and service delivery strategies have shown some promise (

14,

31–

37). Our data underscore the need to develop effective outpatient treatments and services.

Although we incorporated effectiveness components into our design, FISP therapists were hired and paid by the study—a feature of efficacy trials. Other limitations included the relatively brief follow-up interval; limitations associated with the constraints of the emergency department setting (the brief and limited baseline assessment and intervention and the lack of immediate postintervention evaluation of clinical and functioning outcomes), and weak statistical power for clinical outcomes. Although our data supported efficacy of the intervention across two diverse emergency department sites, linkage rates would likely be lower in sites with lower post-emergency department hospitalization rates and insurance, because outpatient treatment is not required or guaranteed in the United States.

Whether a youth attends outpatient treatment is determined by a range of variables. Both hospitalization and the FISP intervention improved treatment linkage, although the FISP led to improved linkage even among hospitalized youths. Repeating the FISP components at hospital discharge might have strengthened clinical impact. We cannot disentangle the effects of the emergency department intervention and care-linkage calls. However, other research indicating the value of a therapy component within the emergency evaluation (therapeutic assessment model) (

30) and more limited impact of a compliance enhancement intervention with high barriers to follow-up treatment (

13) suggest that the combination is needed to overcome the substantial barriers to treatment linkage. The instrumental variables analyses examined linkage to “any treatment” regardless of its quality; the lack of clinical impact may have been due to poor quality of care or inadequate treatment dose.

Similar to the protocol for a hospital's rape crisis team, FISP clinicians were paged on arrival of suicidal patients and delivered the emergency department intervention. There were challenges (youths in the emergency department without parents, limited space in the emergency department, or need to minimize length of emergency department stay), but delivery of the FISP was feasible and accepted in two diverse emergency department settings.

Conclusions

The results of this study support efficacy of the FISP in linking suicidal youths to outpatient mental health treatment after emergency department treatment, a major objective in the U.S. National Suicide Prevention Agenda. Results further highlight the importance of developing effective outpatient mental health treatments and services.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was funded by grant CCR921708 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Additional support was provided by grants R01 MH082856 and P30MH082760 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by a grant from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. The authors thank the youths, families, staff, and colleagues who made this project possible. In addition, the authors thank Lily Zhang for her contributions to data management and analysis and Donald Guthrie, Ph.D., Gabrielle Carlson, M.D., and Lisa Jaycox, Ph.D., for serving on the Data Safety and Management Board. Manuals can be obtained from the first author.

Dr. Asarnow reports receiving honoraria from Hathaways-Sycamores, Casa Pacifica, the California Institute of Mental Health, and the Melissa Institute. Dr. Piacentini has received royalties from Oxford University Press for treatment manuals and from Guilford Press and the American Psychological Association Press for books on child mental health. In addition, he has received a consultancy fee from Bayer Schering Pharma. The other authors report no competing interests.