Sample and data source

Data for this study, which was approved by an institutional review board, were provided by the VA Northeast Program Evaluation Center (NEPEC) and consisted of records of individuals who were admitted into, and discharged from, the GPD program in 2003–2005. The GPD program provides grants to community providers to acquire housing facilities or renovate them (or both) for veterans and provides per diem funds to defray the cost of operations and supportive services. The program provides housing for a period up to two years and is designed as a transitional program leading to permanent housing. Community providers differ in terms of the eligibility requirements for admission and the mix of services provided. Homeless veterans typically enter the program from the street or a shelter but may move into GPD programs directly from a halfway house or other short-term housing situation. To examine program outcomes, we analyzed records for veterans admitted on or after the first day of federal fiscal year 2003 and discharged on or before the last day of fiscal year 2005.

The data set was derived from three sources of information. The first was Form X, a structured interview administered by program staff to veterans entering specialized VA homeless programs that captures sociodemographic, psychosocial, health, housing, and employment information, as well as staff diagnostic impressions based on interview findings and client presentation. The second source was Form D, which captures information (including reason for discharge, place of residence, and work status) at the point of program discharge. The third was the Facility Survey, which provides information about the community provider (such as eligibility requirements and number of housing units). Information from these sources is collected and maintained by NEPEC.

Several restrictions reduced the size of the data set. Because the range of admissions per veteran was large (from one to seven admissions), we used only first admissions for each veteran, resulting in a data set for 17,932 unique veterans who were primarily male (97%) with a mean±SD age of 48.4±8.0. To ensure accurate information from Form X, we required it to have been administered within ten days of program admission. This restriction reduced the data set to 10,188 records. To adequately test the research questions, we also required the veterans to have been homeless for more than 30 days before completion of Form X, to have spent at least 25 of the previous 30 days in a setting that did not prohibit or prevent alcohol or drug use (that is, veterans were not in a prison or hospital), to have been housed in a program that did not exclude veterans with any lifetime history of alcohol or drug abuse, and not to have been discharged from the housing program because of serious general health or mental health problems requiring transfer to acute treatment. Finally, in order to ensure the reliability of the determination of sobriety on admission, we restricted selection of records from programs requiring sobriety at admission (the sober condition) to those that mandated that clients have 14–90 days of sobriety immediately before admission. Programs without a sobriety requirement (the unrestricted condition) admitted clients without regard to alcohol or drug use before admission. The final data set consisted of 3,188 records, 1,250 from programs requiring sobriety at admission and 1,938 from programs not requiring sobriety.

Analyses

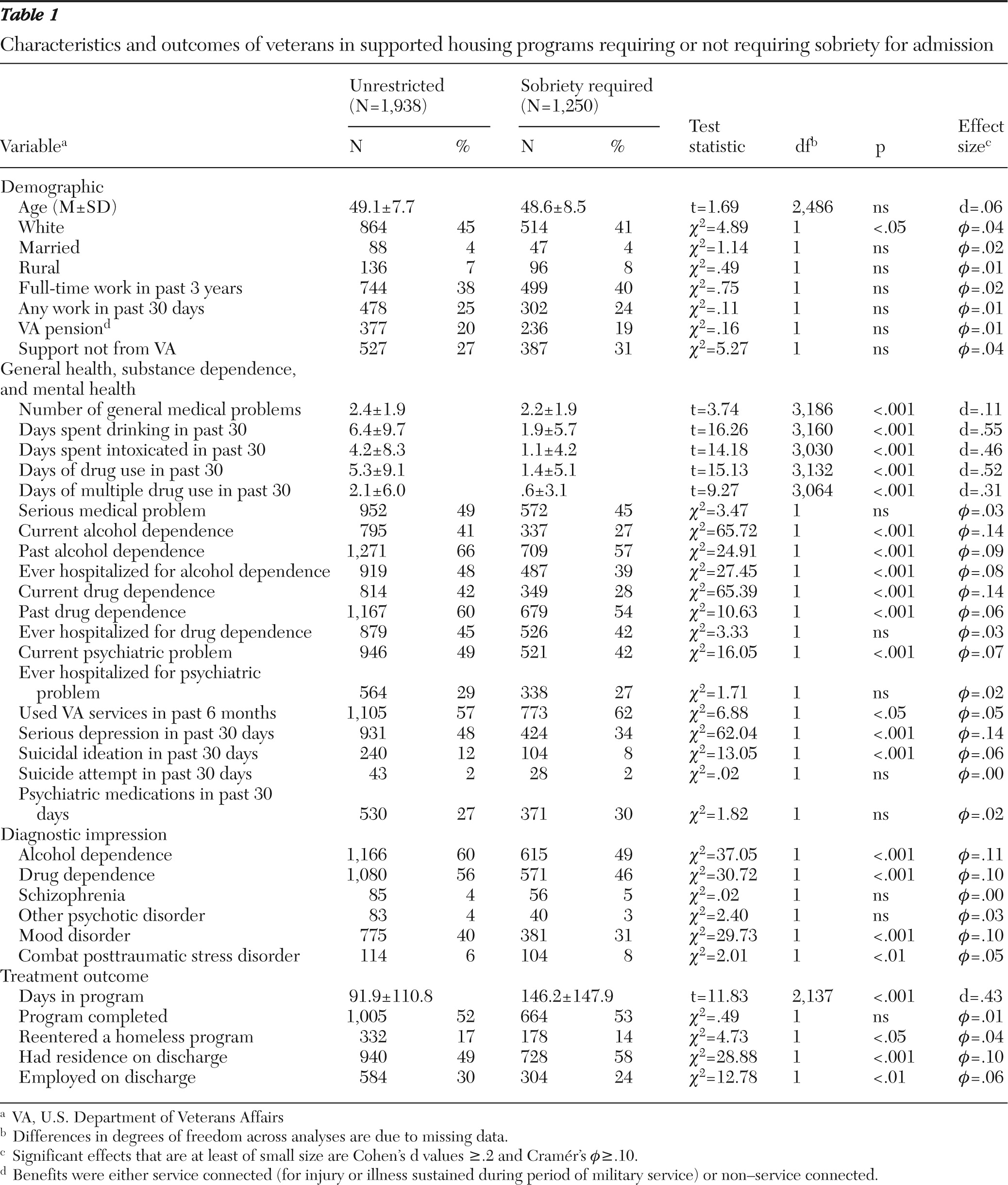

Preliminary analyses examined program characteristics of providers. Descriptive statistics and group comparisons for data from these programs were then conducted on variables in the following domains: demographic characteristics, general medical and psychiatric history, work and financial support, and treatment outcomes. Chi square statistics were calculated to determine significant differences between sobriety and unrestricted conditions on categorical variables. Independent-sample t tests were used to examine differences on continuous variables. When Levene's test for homogeneity of variances was significant, the examination of mean differences was adjusted accordingly.

Because the sample was large, we anticipated that many analyses would produce statistically significant results. To guide meaningful interpretation of findings, we calculated effect sizes for all analyses. Cohen's d was computed to provide an effect size for t tests (

5). Following Cohen's recommendations, we interpreted absolute values for d of .2, .5. and .8 as indicating small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. Absolute values for d that were less than .2 were designated as meaningless, regardless of levels of statistical significance. We calculated Cramér's phi (

ϕ) to provide an effect size estimate for chi square analyses (

6). Phi is a measure of association between two binary variables and is similar to the Pearson correlation coefficient in its interpretation (

7). Again following Cohen (

5), we interpreted absolute values of phi of .10, .30, and .50 as indicating small, medium, and large effect sizes, respectively. Absolute values of phi that were less than .1 were designated as meaningless, regardless of levels of statistical significance. Because we focused interpretation of results primarily on effect sizes, we did not correct p values for the number of analyses that were conducted.

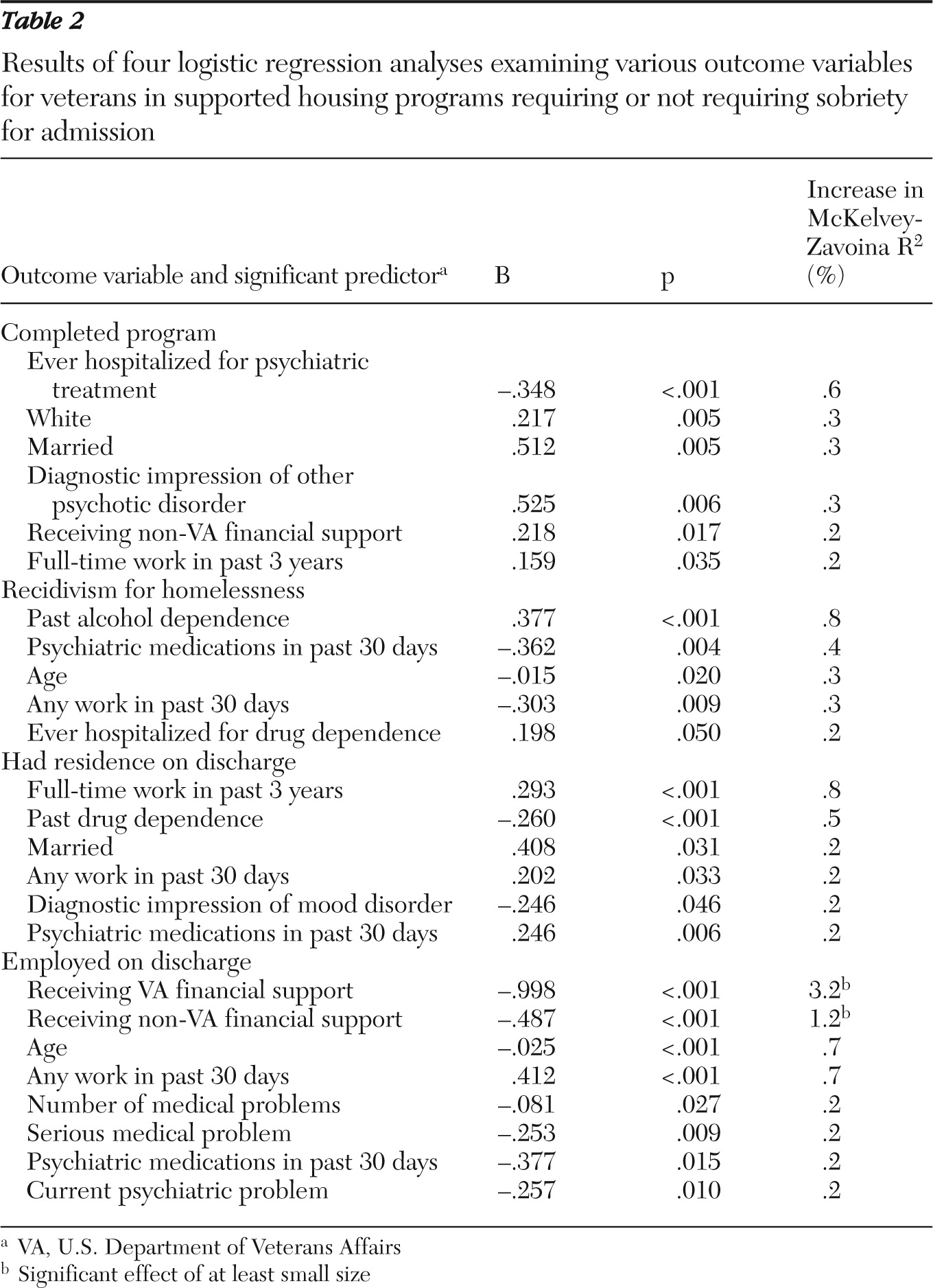

Logistic regression was used to examine predictors of treatment outcomes, with program completion, recidivism for homelessness, housing status, and employment status as outcome variables. In these analyses, predictor variables (demographic variables and psychiatric history variables) and condition (sobriety requirement versus unrestricted) entered the analysis under the forward method of entry with the Wald statistic as a criterion. In order to estimate the amount of variance in outcomes explained by these variables, we calculated the McKelvey-Zavoina index per the recommendation of DeMaris (

8). This index also serves as a measure of effect size, with an explanation of 1% of the variance in the dependent variable considered to be the lower boundary of a small meaningful effect (

5). Separate logistic regression analyses were conducted for each outcome variable.

The characteristics of our sample and program did not allow us to replicate exactly the analyses of Edens and colleagues (

3). They compared substance-abusing housing clients and abstaining housing clients who were being served by the same set of programs. In our analyses, participants in the programs with admission conditional on sobriety were by definition sober for at least two weeks, whereas most participants (60%) in the programs in the unrestricted condition had used alcohol or drugs in the 30 days prior to program admission. We did, however, examine whether there was an interaction of past alcohol or drug abuse (more than 30 days prior to program entry) with program type (sobriety requirement versus unrestricted) on outcomes. These analyses used the same logistic regression approach described above. All analyses were carried out in SPSS, version 18.0 (

9).