It has been widely acknowledged for several decades that individuals with depression are undertreated (

1–

4). The undertreatment is attributable to multiple factors, including poor recognition of depression by physicians (

5,

6), delivery of most treatment outside the mental health specialty sector or outside structured collaborative care (

7,

8), inadequate dosages of antidepressants (

9,

10), and short duration of antidepressant pharmacotherapy (

11,

12). In the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (

13), 41% of respondents with

DSM-IV mood disorders received no treatment in the prior year.

The consequences of undertreatment of depression are well established. For the individual, inadequate treatment can lead to a poor prognosis, including a more severe, chronic disease and higher frequency of relapse and recurrence (

14). On a societal level, direct and indirect costs of depression in the United States were $83.1 billion in 2000 (

15), with increased health care costs in subsequent years. Accurately and efficiently identifying the factors that are associated with initiation and continuation of antidepressant pharmacotherapy may foster improved clinical management and in turn reduce both individual and societal costs.

Research suggests that sociodemographic factors (

16–

20), medical and psychiatric comorbidities (

21–

27), and health care utilization (

28) are all associated with receipt of care for depression. Several studies in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) during the past decade have assessed the quality of depression pharmacotherapy (

29–

31), and it has been acknowledged that “more work is needed to align current practice with best-practice guidelines” (

29). Treatment for recurrent depression may benefit greatly from combined pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy (

32). Because patients frequently do not receive the guideline-recommended number of psychotherapy visits (

33) after a depression diagnosis, the study reported here focused on receipt of pharmacotherapy.

Depression is understood to be a chronic disease, and the average individual with depression experiences multiple recurrences over his or her lifetime (

34). Although the existing literature provides a good foundation for understanding and treating this disorder, there are several ways that current knowledge can be extended. Relapse is common and much remains unknown about patients who have multiple episodes of depression. We are unaware of any studies of treatment utilization by patients with recurrent depression. The study reported here sought to fill this gap in the literature by determining sociodemographic characteristics, medical and psychiatric comorbidities, and health care utilization factors associated with adequate antidepressant pharmacotherapy.

Methods

Data were obtained from sources maintained by the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) National Medical Care data sets, which include inpatient and outpatient

ICD-9-CM diagnoses, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes, Pharmacy Benefits Management records, and sociodemographic information. Data were gathered back to fiscal year (FY) 1999, the year for which national data are considered complete. The data include all VHA health utilization encounters and are maintained by the VHA Office of Information, Austin Information Technology Center (

www.virec.research.va.gov/datasourcesname/medical-sas-datasets/sas.htm).

Eligibility

Population cohort.

We derived a sample of VA patients with recurrent episodes of depression from a larger retrospective cohort study of depression and incident cardiovascular outcomes (

35). The larger cohort (N=236,681) was selected to be free of heart disease at baseline (no primary or secondary

ICD-9-CM codes 402–405, 410–417, and 420–429) and included all depressed patients—as defined by

ICD-9-CM codes 296.x, 300.4, and 311—who used the VHA in the year 2000. After selection, the definition of depression was further refined (

36) to require one inpatient or two outpatient primary

ICD-9-CM codes of 296.2, 296.3, 300.4, or 311. The remaining sample included 96,612 depressed patients.

Sample cohort.

From the depressed cohort we created a subset of patients experiencing an episode of recurrent depression in order to determine predictors of receipt of antidepressant pharmacotherapy. We used guidelines from the

FY 2007 Q3 Technical Manual for the VHA Performance Measurement System (

37) to define incident episodes of depression by identifying a “clean period” before the start date of the index episode, during which a patient could have no antidepressant prescriptions for 90 days and no

ICD-9-CM codes for depression for 120 days. If these criteria were met, then the beginning of an index episode, the first appearance of an

ICD-9-CM code, was identified. New antidepressant prescriptions were allowed between 30 days before the

ICD-9-CM code and 14 days after the code in order to capture prescriptions received before clinic visits and those filled several weeks after such visits. New episodes were considered recurrences because all patients entered the cohort with a history of depression, experienced a clean period with no

ICD-9-CM codes for depression or an antidepressant prescription, and then experienced a new episode of depression. It has not been determined whether this is analogous to the clinical period of recovery used to define a recurrent episode in clinical practice, but it is the accepted definition for administrative data.

We identified 29,352 individuals with a recurrent episode of depression who met the inclusion criteria. From this total, we excluded 2,266 patients without sufficient follow-up data (less than six months) and 316 patients who were younger than 25 or older than 80. Our final cohort included 26,770 depressed patients with a recurrent episode during the study time frame. [A flowchart depicting selection of the final sample is available in an online supplement to this article at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Outcome variables

Treatment was defined as a four-level categorical variable: no antidepressant pharmacotherapy, some antidepressant pharmacotherapy, adequate acute-phase pharmacotherapy, and adequate continuation-phase pharmacotherapy. All categories were defined to be mutually exclusive. Individuals were categorized as receiving some treatment if they filled one or two prescriptions but fell short of meeting the guideline for adequate acute-phase pharmacotherapy. We included all antidepressants available in the U.S. market throughout the study (FY 1999–2006). Drugs not listed in the VA formulary were included because physicians could prescribe “off-formulary” when clinically indicated (personal communication, D. Nurutdinova, March 2009).

Our main outcome of interest was receipt of adequate acute- and continuation-phase treatment. We operationalized adequate acute-phase treatment according to the

FY 2007 Q3 Technical Manual for the VHA Performance Measurement System (

37), which follows the guidelines used by the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) (

38). The guideline for adequate acute-phase treatment requires that a patient who is diagnosed as having a new or recurrent episode of depression receive at least 84 days of antidepressant treatment during the 114 days (12 weeks) from the index prescription date, with no more than a 30-day gap in prescription fills.

Individuals were categorized as having received adequate continuation-phase treatment if they met or exceeded the minimum criterion of 180 days of prescribed antidepressants over a 210-day period. This group consisted of patients who met the guideline for continuation-phase treatment and patients who met the guideline for maintenance-phase treatment. Adequate maintenance treatment was defined as exceeding the continuation guideline (that is, the prescription continued to be filled after 210 days).

The number of patients who received adequate continuation-phase treatment was very small (N=204) compared with the number who met the guideline for adequate maintenance-phase treatment (N=3,315). If patients remained in treatment for at least 180 days (the duration of the continuation phase), they tended to remain in treatment for their duration in the cohort. Continuation and maintenance treatment were therefore combined to form the category of adequate continuation-phase treatment.

Factors

Sociodemographic factors.

Treatment of depression has been shown to vary by sociodemographic factors (

39). Sociodemographic factors included in the study were age, gender, race, marital status, and type of insurance (VA benefits only versus other insurance). Patients who had other health insurance may have been receiving treatment in the private sector in addition to VA care, which would have reduced the likelihood of documenting all of their health care utilization, including treatment of depression. Sensitivity analyses were performed to determine whether including patients with additional insurance would bias the results. No significant differences were found when these patients were excluded, so they were retained in the analyses.

Medical comorbidities.

The prevalence of depression is higher among patients with certain general medical comorbidities compared with those who have depression alone (

40). The following disorders were included because they might have affected the likelihood of receiving treatment for depression: HIV (

ICD-9-CM codes 042–044), cancer (V1046, 238.6, 273.0, 170, 171, 174–176, 179, 190–195, 140–149, 150–159, 160–169, 180–189, and 200–209), incident myocardial infarction (410 and 412), and diabetes (250.x0, 250.x2, 357.2, 362.0, and 366.41 or a prescription for an antidiabetic medication or insulin). A medical comorbidity was documented if one

ICD-9-CM code was present in the patient's data.

Anxiety disorders.

Anxiety disorders are highly comorbid with depression and may increase the likelihood of receiving specialty mental health care (

41). The following anxiety disorders were included: anxiety disorder unspecified (

ICD-9-CM code 300.0), generalized anxiety disorder (300.02), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (309.81), social phobia (300.23), panic disorder (300.01), obsessive-compulsive disorder (300.3), agoraphobia (300.21 and 300.22), and specific phobias (300.29 and 300.20). We required a minimum of two outpatient diagnoses or one inpatient diagnosis within a single 12-month period at any time before the onset of depression.

Substance use disorders. Because alcohol abuse and dependence (ICD-9-CM codes 291, 303, and 305.0) and illicit drug abuse and dependence (304.0–304.9, 305.2–305.7, and 305.9) were highly collinear (r=.83), we combined the two diagnoses into one substance abuse or dependence variable. We also modeled nicotine dependence (ICD-9-CM 305.1 and V15.82). These diagnoses may also be related to receipt of mental health care.

VA health care utilization.

Two variables were used to measure use of VA health care. Use of health care may increase the likelihood of receiving mental health treatment, and it was included in models to control for overall VA utilization by using the mean number of VA clinic visits per month. We also created a variable for the location in which the index depression ICD-9-CM code was received (mental health setting, primary care, emergency department, or other setting) to test for differences in antidepressant pharmacotherapy by sector of care.

Statistical analysis

Univariate comparisons of potential predictor and outcome variables were made by first computing chi square tests to determine whether categorical predictors were significantly related to duration of antidepressant pharmacotherapy. Analysis of variance was used to test whether the mean difference between continuous variables was significantly related to level of antidepressant pharmacotherapy. All variables found to be significantly associated with the outcome at .05 or less were entered into a multinomial logistic regression model. The outcome was four levels of treatment with no antidepressant pharmacotherapy as the reference; the other levels were some pharmacotherapy, adequate acute-phase pharmacotherapy, and adequate continuation-phase pharmacotherapy. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.2, and alpha was set at .05. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at all participating institutions.

Results

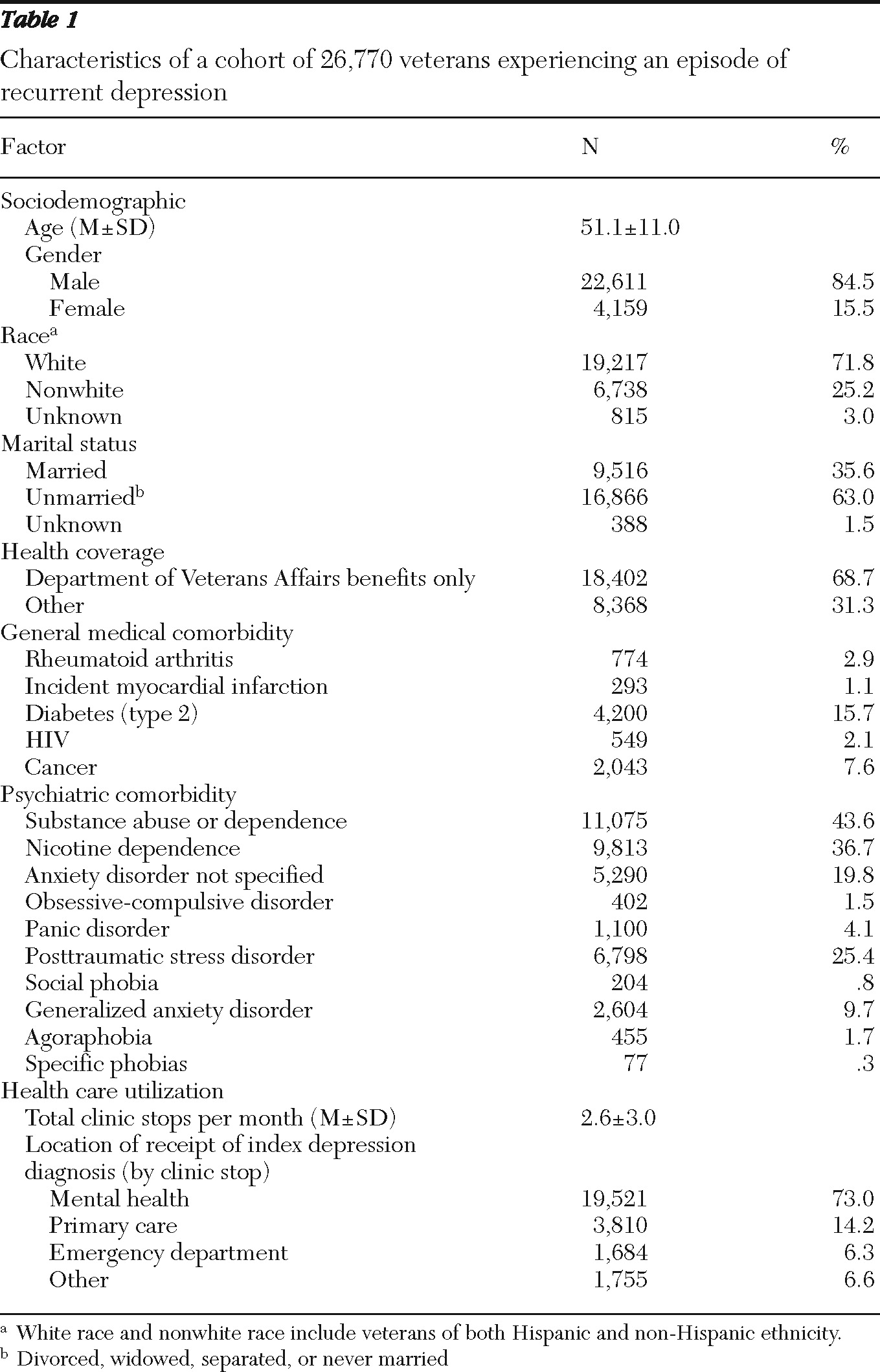

Table 1 presents data on sociodemographic characteristics, medical and psychiatric comorbidities, and VA health care utilization of the 26,770 cohort members experiencing an episode of recurrent depression. Most patients were men (84.5%), and more than two-thirds were white (71.8%). The mean age was 51.1, and almost two-thirds were divorced, separated, widowed, or never married (63.0%). The most common general medical comorbidities were type 2 diabetes (15.7%) and cancer (7.6%), and the most common psychiatric comorbidities were substance abuse or dependence (43.6%), nicotine dependence (36.7%), PTSD (25.4%), and anxiety disorder unspecified (19.8%). The mean number of clinic stops per month was 2.6, and most patients received their index depression diagnosis in a mental health specialty setting (73.0%).

Bivariate analyses of antidepressant pharmacotherapy

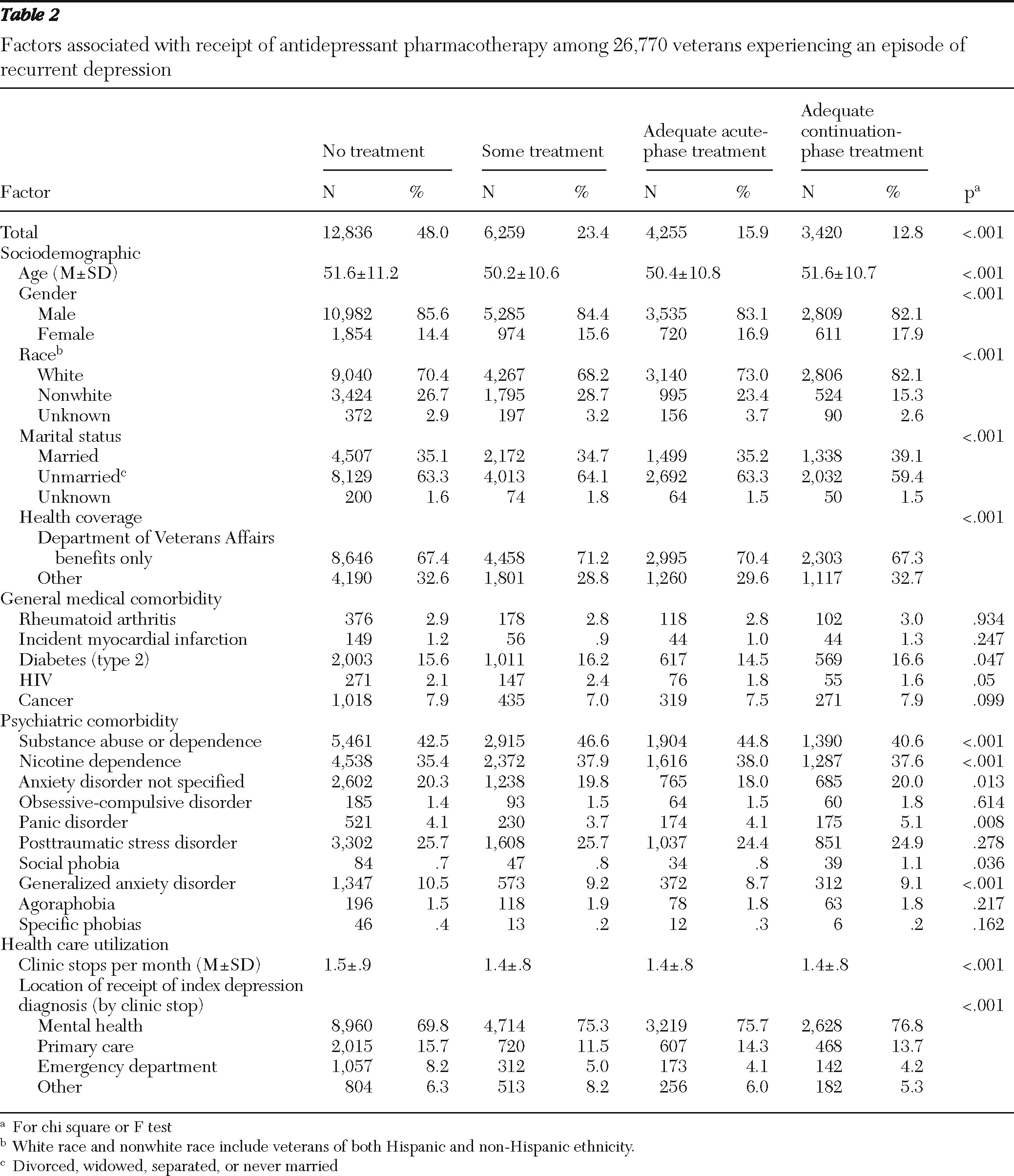

In this cohort of 26,770 patients with recurrent depression, 48.0% received no antidepressant treatment, 23.4% received some treatment, 15.9% received adequate acute-phase treatment, and 12.8% received adequate continuation-phase treatment. Associations between level of treatment and factors are shown in

Table 2. Because of the large sample size, many of the comparisons were statistically significant but may not be meaningfully different in magnitude. However, several contrasts of greater magnitude are noted. Differences by race were found in the level of treatment received. Among white patients, the proportion that received adequate continuation treatment was greater than the proportion that received no treatment (82.1% compared with 70.4%). In contrast, among nonwhite patients, the proportion that received no treatment was greater than the proportion that received adequate continuation treatment (26.7% compared with 15.3%). Overall, most patients were diagnosed in the mental health sector, regardless of the level of treatment they received. Among patients who received a diagnosis in the mental health sector, more patients received adequate continuation-phase treatment than no treatment or some treatment (76.8% versus 69.8% and 75.3%, respectively). Of patients who received a diagnosis in primary care, more received no treatment than adequate continuation treatment (15.7% versus 13.7%). This same pattern was observed for patients diagnosed in the emergency room; among these patients, more received no treatment than received adequate acute treatment (8.2% versus 4.1%). Among patients diagnosed in other settings, more patients received some treatment than received adequate continuation treatment (8.2% versus 5.3%).

Multivariate model

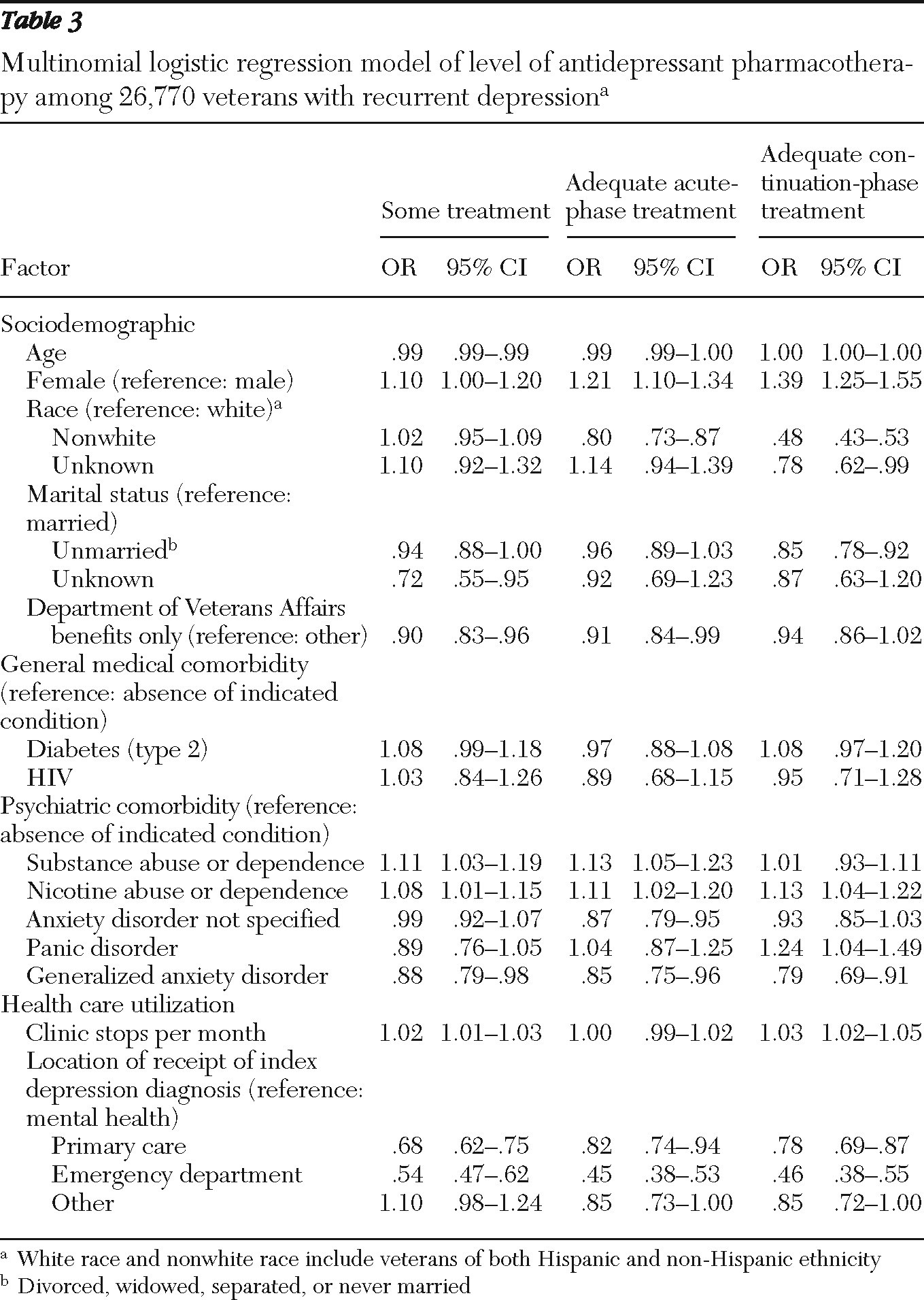

Table 3 presents odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the multinomial logistic regression model with the four-level antidepressant pharmacotherapy outcome variable (the reference was no antidepressant treatment). Compared with male patients, female patients were more likely to have received both adequate acute-phase treatment (OR=1.21) and adequate continuation-phase treatment (OR=1.39). Nonwhite patients were less likely than white patients to receive either adequate acute-phase treatment (OR=.80) or adequate continuation-phase treatment (OR=.48). Patients with substance abuse or dependence were more likely than those without this diagnosis to have received both some treatment (OR=1.11) and adequate acute-phase treatment (OR=1.13). Nicotine dependence was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving all levels of treatment (range of ORs 1.08–1.13).

Comorbid generalized anxiety disorder was associated with a decreased likelihood of receiving all levels of treatment (range of ORs, .79–.88), whereas panic disorder was associated with a 24% greater likelihood of receiving adequate continuation-phase treatment (OR=1.24). Finally, receiving an index depression diagnosis in either primary care or in the emergency department instead of in the mental health specialty sector was associated with a decreased likelihood of receiving all levels of treatment (range of ORs for primary care, .68–.82; for the emergency department, .45–.54).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to identify sociodemographic, psychiatric, general medical, and health care utilization factors associated with a likelihood of receiving antidepressant treatment for depression (some, adequate acute-phase, and adequate continuation-phase treatment) in a large cohort of depressed VA patients who were experiencing an episode of recurrent depression. We found that female patients, those with substance abuse or dependence, those with nicotine dependence, and those with panic disorder were more likely to receive adequate acute-phase or continuation-phase treatment than to receive no treatment. Patients who were not white, those who were unmarried, those who had VA benefits only, those with generalized anxiety disorder, and those whose index diagnosis was received outside the mental health specialty sector were less likely to receive guideline-concordant care.

As Charbonneau and colleagues (

29) found in their study of patients with a history of depression, we found that nonwhite race and being unmarried were associated with inadequate duration of care. However, Charbonneau and colleagues did not find any significant associations between treatment receipt and comorbid anxiety or alcoholism. They found that treatment received exclusively in the primary care sector was associated with a lower likelihood of adequate treatment duration. We found that simply receiving an index diagnosis in primary care as opposed to the mental health sector was associated with a lower likelihood of adequate duration of treatment. Our finding that having a substance use disorder or panic disorder was associated with a greater likelihood of receiving care may indicate that our cohort had a more complex overall profile than that of Charbonneau and colleagues, which may be the case for a cohort of patients with recurrent depression. Also, these substance use disorders and panic disorder may be less common among persons with single-episode depression and thus less likely to influence receipt of care.

The VA system removes many of the barriers to care found in the private sector. However, the overall rate of adequate treatment in this population remained low, with only 28.7% of depressed patients getting adequate acute- or continuation-phase antidepressant pharmacotherapy for their depressive episode. This rate is much lower than rates found by Busch and colleagues (

30); those rates were 84.7% for the VA and 81.0% for the private sector for acute-phase treatment alone. The difference may be due to how depressive episodes were defined. The studies reported by Busch and colleagues required only a single

ICD-9-CM code for major depression, whereas our study required either two outpatient codes or one inpatient code within a 12-month period. Busch and colleagues (

30) also reported much higher rates of adequate treatment than were found in our study. However, some of the factors that they found to be associated with receipt of adequate treatment were similar to those in our study. For instance, they found that receipt of guideline-concordant acute and continuation treatment in both the VA and the private sector was associated with female gender and anxiety or adjustment reaction. Future research is warranted to examine whether various depression subtypes are associated with treatment outcomes.

Two findings of importance to the VA system are that patients who had only VA benefits were slightly less likely to receive adequate acute-phase treatment and that patients who received their depression diagnosis outside the specialty mental health sector were less likely to receive adequate acute- or continuation-phase treatment. Having additional insurance is likely a marker for greater socioeconomic resources, which would give these veterans more opportunities for obtaining health care in the community, as well as improved access to basic resources, such as transportation. Receipt of a depression diagnosis in primary care may lead to lower-quality care because of the competing demands of primary care physicians (

26,

42) and the large burden placed on them. Individuals who receive a diagnosis in the emergency department may not be followed up in ambulatory care after an acute episode. More work needs to be done to identify barriers to high-quality care for patients in these sectors.

In general, research on community-based care shows that most patients receive treatment for depression in primary care (

43). In our clinical sample, we found that over 70% received their index diagnosis of depression, as indicated by the

ICD-9-CM and clinic stop codes in the patient data, in a specialty mental health setting. This rate is closer to that observed in other clinical cohorts, such as the VA National Registry for Depression, which found that among depressed VA patients, 40% received primary care only and 56% received more than half their care in mental health specialty clinics (

44). The higher rate of specialty mental health care in our study may be associated with the fact that our patients were experiencing recurrent depression rather than a first episode of depression.

Limitations

Administrative data have inherent limitations compared with data from clinical trials and with primary collection of data. Misclassification is a risk; however, VA administrative records have shown better than 99% agreement between administrative files and clinical records for inpatient diagnoses such as acute myocardial infarction, diabetes, schizophrenia, and ischemic heart disease (

45). For secondary diagnoses, agreement was 97% for neurotic disorders. The role of patient beliefs about psychiatric care, stigma, and self-efficacy are all potential contributors to receipt of care; however, these variables are not available in administrative data. Because of the difficulty of determining specific types of psychotherapy on the basis of CPT codes in administrative data, we were unable to include behavioral therapies for depression in this project. Psychotherapy can be an integral part of recovery from depression, and further research is warranted to develop an algorithm for capturing modes of behavioral therapy from administrative data.

Additional potential limitations include lack of information about patients' health behaviors, including substance abuse treatment, receipt of care outside the VA system, and use of prescriptions filled at non-VA pharmacies and over-the-counter drugs. Also, the findings are specific to veterans receiving care in the VA system and may not generalize to other populations of patients with recurrent depression. Because of the increased prevalence of use of specialty mental health care in the VA, these findings may not generalize to the private sector.

Strengths

By selecting our cohort from all patients meeting criteria for depression, we were able to decrease the heterogeneity of our sample and look only at recurrent episodes of depression. As acknowledged, using administrative data we could not ensure with the same degree of precision as with a clinical diagnosis that each patient was experiencing a recurrent episode of depression. However, our depression criteria and sample selection provided a stricter degree of certainty about the diagnosis than in most studies reported in the literature. The large sample permitted us to simultaneously model multiple predictors, including less common incidents such as cancer. These results should be generalizable to most VA patients.

Reliability of administrative ICD-9 codes

VA administrative records have been shown to have adequate reliability for identifying patient diagnoses compared with written patient charts (

45). In administrative data having two visits for depression has been shown to have 99% positive predictive value for a diagnosis of depression (

36). A large body of literature from a broad range of medical specialties has utilized VA national databases and

ICD-9-CM codes for clinical epidemiology and outcomes research, including studies using definitions of depression identical to ours (

35,

46). Others have used very similar definitions of depression (

47), anxiety disorders (

48), and other medical conditions (

49).

Conclusions

We are not aware of previous studies that have looked specifically at factors associated with receipt of treatment for episodes of recurrent depression; past studies have looked at patients with first episodes and those with recurrent episodes as a heterogeneous group. It is interesting that as many factors appear to predict episodes of recurrent depression as predict first episodes and that these factors are similar. It is hoped that identification of patient groups at high risk for inadequate duration of treatment will lead to improvements in care. Physicians should emphasize to patients the importance of maintenance-phase pharmacotherapy, especially to those at high risk of not receiving such care—for example, those with comorbid conditions and from racial-ethnic minority groups.

In this study of adequate acute- and continuation-phase depression treatment for patients with recurrent depression, the overwhelming majority of patients who met the guideline for adequate continuation-phase treatment also continued their treatment into the maintenance phase (94%). These patients were categorized as continuation-phase patients because they met this guideline and there is currently no HEDIS measure to govern who should receive maintenance-phase treatment or how it should be operationalized. In the literature, guidelines for maintenance-phase treatment advise 12 to 36 months of pharmacotherapy for patients with greater chronicity or severity of depression (

50). In future studies, identifying the factors associated with adequate maintenance-phase treatment is critical to improving care for patients with recurrent or chronic depression.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Ms. Garfield is supported by an assistantship from the Graduate School at Saint Louis University. Dr. Scherrer is supported by a Career Development Award from VA Health Services Research and Development. Dr. Nurutdinova is supported by a Veterans Integrated Service Network 15 Career Development Award. Dr. Fu is supported by grant K07CA104119 from the National Institutes of Health.

The authors report no competing interests.