The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is implementing systemwide primary care mental health services (

1). Primary care mental health within the VHA uses a blended model of colocated, collaborative mental health specialists and care managers to improve screening and management of common mental health conditions, including depression, alcohol misuse, and posttraumatic stress disorder, within primary care settings (

2,

3). Implementation and specific program characteristics vary among sites, depending on local resources. However, by enhancing primary care-based treatment of common mental health conditions, an overarching program goal is to increase access to specialty mental health clinics for patients with more severe or complex mental illnesses (

1).

Previous research has investigated the impact of providing mental health services in primary care on the detection of mental health conditions; however, effects of such programs on specialty mental health care are largely unknown (

4,

5). Primary care mental health could influence the volume of referrals to specialty mental health care, depending on the number of new cases identified and the percentage of cases treated within primary care instead of in specialty clinics. This study sought to advance understanding of differences in the volume and characteristics of new visits to specialty mental health clinics by primary care patients at VHA facilities with mental health services integrated into primary care and those without it. Study findings may inform expectations regarding the impact of primary care mental health implementation on specialty mental health clinic services and workforce needs.

Methods

We conducted a facility-level analysis of all large (>5,000 unique users) VHA facilities (N=294). We compared facilities that implemented primary care mental health before April 1, 2008 (N=118), with facilities that had not implemented primary care mental health by April 1, 2009 (N=142), and excluded facilities that developed primary care mental health between those time periods (N=34). Implementation of mental health services in primary care was determined by facility use of an administrative stop code, which is part of the decision support systems (DSS) identifier and is linked to primary care mental health service encounters. This stop code became available for VHA facility use, subject to national program office approval, on October 1, 2007, and has been used to study differences in primary care diagnosis of mental health conditions (

5). Measures of facility size (number of primary care patients), academic affiliation, and location (urban versus nonurban and U.S. region) were also constructed.

As part of the VHA National Evaluation of Primary Care Mental Health Integration, patient data were obtained from the VHA's National Patient Care database with a 30% simple random sample of patients who received primary care services in any VHA facility between October 1, 2007, and March 31, 2009. From this sample, we identified new visits to specialty mental health clinics at the study facilities between April 1, 2008, and March 31, 2009, that occurred within three months after a primary care visit and with no specialty mental health clinic visits in the preceding year.

Mental health diagnoses received at these new visits to specialty mental health clinics were categorized on the basis of

ICD-9-CM codes. To further characterize illness severity, we divided depression, anxiety, and substance use diagnoses into categories of greater and lesser severity. For example, depression diagnoses were split into major depressive disorder and nonmajor depression (depression not otherwise specified and dysthymic disorder). Mental health V codes, which clinicians use to indicate mental health concerns not meeting criteria for a disorder, were also measured. We determined whether patients had comorbid mental health conditions, excluding less severe conditions when they occurred within the same diagnostic domain (for example, alcohol abuse and alcohol dependence together counted only as alcohol dependence). We measured medical comorbidity using the Charlson Comorbidity Index for the year before the mental health clinic visit (

6) and separately identified patients with medical comorbidities who had either major depressive disorder or nonmajor depression, given that management of depression is a common focus for primary care mental health programs.

For each facility we determined the percentage of primary care patients whose diagnoses at a new visit to a specialty mental health clinic fell into each diagnostic category. Mental health clinic treatment initiation was calculated by dividing the number of primary care patients with a new mental health clinic visit by the total number of primary care patients within each facility. The total number of specialty mental health clinic visits in the 12 months after the initial visit was also calculated for each patient and averaged for each facility. Means and percentages for facility-level demographic characteristics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, and marital status) were also calculated for inclusion in the adjusted analyses.

Independent-samples t tests were used to test for significant differences in the frequency of specific diagnoses between primary care facilities with and without integrated mental health services. Adjusted analyses were performed by fitting a multivariable regression model for each diagnostic category, with diagnosis rate as the outcome variable and facility demographic and other characteristics (size, academic affiliation, urbanicity, and U.S. region) as predictor variables. Regression coefficients were then used to calculate diagnosis rates, adjusted for facility characteristics at their means or modes. We adjusted alpha using a Bonferroni correction for the 21 outcomes investigated, with a resulting significance threshold of p=.0024.

Results

Of the 49,957 VHA primary care patients in our sample with new visits to specialty mental health clinics, 26,982 (54.0%) were treated in facilities with primary care mental health services. Primary care mental health facilities and primary care facilities that did not offer integrated mental health care did not significantly differ with regard to the mean age (55.7 versus 56.2) of primary care patients newly seen in specialty mental health clinics or the percentages of the sample that were male (93.3% versus 92.9%), white (67.1% versus 69.2%), African American (18.3% versus 16.0%), or Hispanic (3.4% versus 5.5%). New specialty mental health clinic users at primary care mental health facilities were less likely than those at primary care facilities without integrated mental health care to be married (45.8% versus 50.4%, p<.001). Facilities in the Northeast or Western U.S. regions were more likely to have a primary care mental health program than those in the South or Upper Midwest, and primary care facilities with integrated mental health care were larger (13,406 versus 9,124 mean unique primary care patients; p<.001) and were more likely to have an affiliation with an academic institution (67.8% versus 19.0%, p<.001).

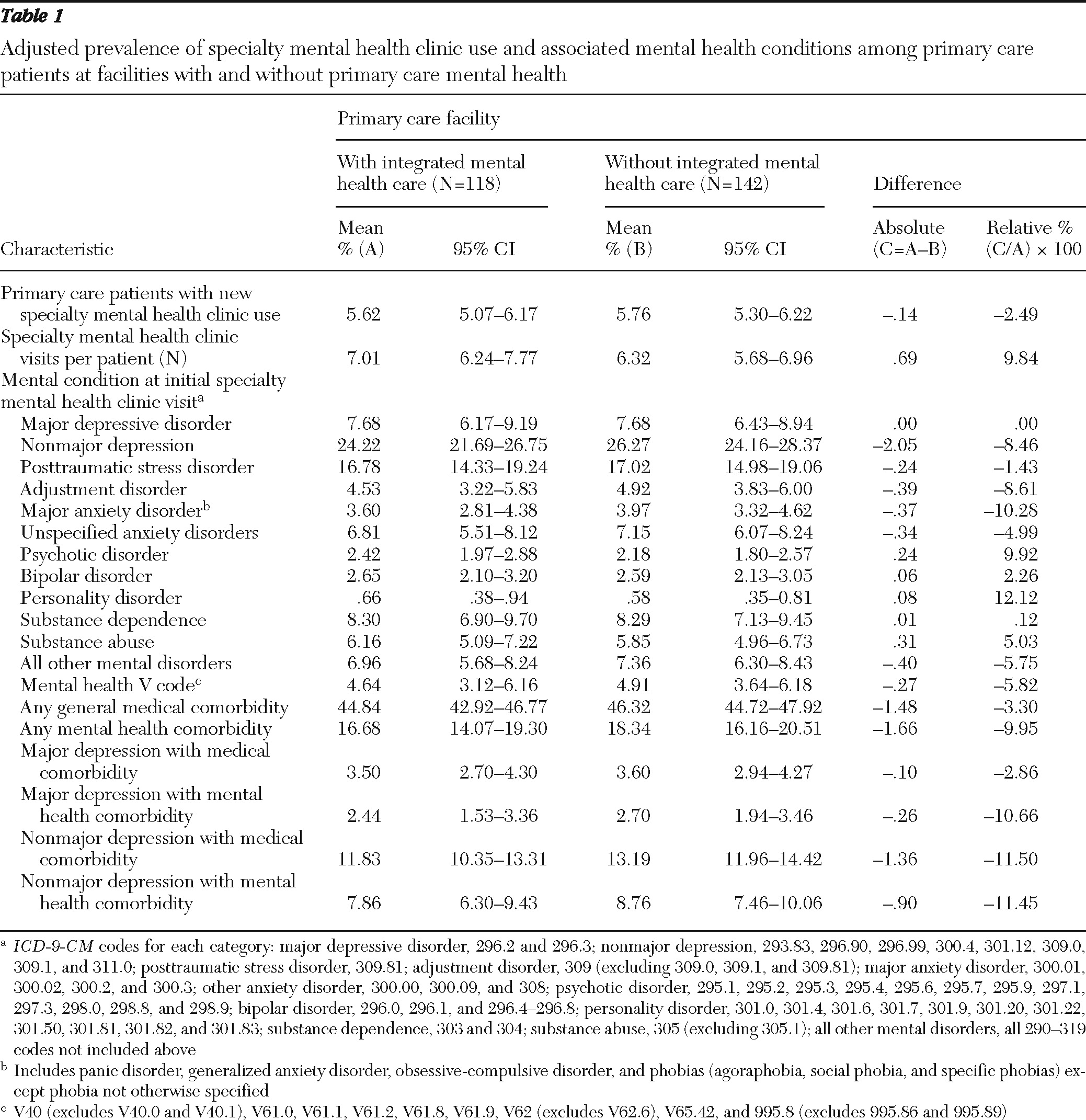

Initiation of treatment at a specialty mental health clinic did not differ between primary care mental health facilities and those without the service in either unadjusted (5.6% versus 5.8%) or adjusted analyses (

Table 1). Patients who initiated mental health treatment at primary care facilities with integrated mental health services averaged an unadjusted 8.1 total specialty mental health clinic visits compared with 6.5 visits among patients at primary care facilities without integrated mental health care; however, after adjustment for facility characteristics, primary care services for mental health was not a statistically significant predictor of total specialty mental health clinic visits.

With regard to diagnoses, patients initiating specialty mental health clinic treatment at primary care mental health facilities had higher rates of substance use disorders (8.4% versus 6.7%, p=.014) and lower rates of nonmajor depression (22.7% versus 25.2%, p=.018); however, these differences were not statistically significant after adjustment for facility characteristics and multiple comparisons.

Discussion and conclusions

In the early period of systemwide implementation, provision of primary care mental health services within the VHA health system was not associated with differences in new use of specialty mental health clinics or diagnoses received in specialty mental health clinics by primary care patients. In a post hoc power calculation, using α=.0024, we had 80% power to detect moderate standardized mean differences (that is, effect size) of .48 or greater. Facilities planning to implement a primary care mental health program should therefore not assume that they will experience large short-term changes in the number of primary care patients referred for specialty mental health care or the complexity of their illnesses.

Our findings do not imply that primary care mental health services have been unsuccessful in detecting and treating patients with mental health problems entirely within primary care, because these functions could occur without affecting the number of patients referred to specialty care. The similar numbers of follow-up visits at both types of facilities suggest that in addition to similar rates of specialty treatment initiation, patients at primary care mental health facilities also appear no more likely to be referred for one-time consultation or short-term management.

This study is limited by our use of diagnostic categories and comorbidity rates as crude measures of mental illness severity. Also, although the presence of primary care mental health services was determined systematically through use of an administrative code, the specific services offered and the degree and fidelity of implementation of integrated mental health care were not measured and could vary widely among facilities. Finally, these findings may not apply to nonveteran populations or health systems that use other forms of reimbursement (that is, fee-for-service arrangements) or referral requirements.

As primary care mental health programs mature, they may affect use of specialty mental health clinics over longer periods than we observed. Future work should measure the long-term consequences of primary care mental health programs on specialty mental health care and the implications for the treatment of patients with mental health problems in these settings.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was funded by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Primary Care-Mental Health Integration National Evaluation and by the VA Health Services Research and Development Service (CD2 07-206-1 and CD2 10-036-1).

The authors report no competing interests.