Determining whether court-ordered psychiatric outpatient commitment reduces arrest among people with mental illnesses is critically important for multiple reasons. Arrest is a devastating experience for individuals and their families, and its societal costs are enormous (

1). Further, given the intense debate about outpatient commitment, it is important to assess whether legally mandated outpatient treatment forestalls the subsequent and even more noxious forms of coercion that arrest brings. This possible trade-off of a milder form of coercion for a more severe one could represent useful information in considering the value of outpatient commitment.

New York State established outpatient commitment in 1999 through Mental Health Law 9.60 (known as “Kendra's Law”), under which court-ordered assisted outpatient treatment (AOT) could be mandated for certain individuals with mental illness and a history of multiple hospitalizations or violence toward self or others. Specific legal criteria are required for an assignment to AOT, including a judgment based on a history of treatment noncompliance whereby the individual is considered unlikely to voluntarily adhere to treatment and has a high likelihood of benefiting from mandated treatment. Individuals entering AOT are assigned a case manager and prioritized for enhanced services that include housing and vocational services.

There are several reasons why outpatient commitment approaches such as AOT might reduce the risk of arrest. Comprehensive reviews of outpatient commitment report lower rates and durations of subsequent psychiatric hospitalizations, enhanced adherence to medication, and reduced disruptive symptoms (

2,

3). Two recent studies conducted in New York support this general conclusion. In the first, New York City residents receiving AOT were found to have reduced suicide risk, better illness-related social functioning, and lower rates of violence than a propensity score-matched comparison group (

4). In the second, AOT recipients' hospitalization rates were lower while receiving AOT than they had been before AOT (

5). Broad-based benefits like these might be expected to reduce arrests. On the other hand, most mental health interventions aim to reduce symptoms and associated impairments and do not directly target factors leading to arrests of people with mental illnesses (

6). Also, outpatient commitment involves heightened surveillance that could elevate the chance of being apprehended. Finally, some argue that, in the long run, the coercion associated with outpatient commitment impedes treatment engagement (

7), thereby facilitating untoward outcomes such as arrest.

Existing evidence on outpatient commitment and arrest

There have been only two randomized trials to examine the consequences of outpatient commitment for arrests (

8,

9). In the first study, Steadman and colleagues (

8) found overall arrests during an 11-month follow-up to be almost identical for individuals assigned to outpatient commitment (18%) and a control group who did not receive outpatient commitment (16%). In the second study, Swartz and colleagues (

9) reported no significant difference in overall arrests during a 12-month follow-up (outpatient commitment group, 18.6%; control group, 19.3%). Although these studies showed no significant effect of outpatient commitment on arrest, three facts suggest the need for additional investigations. First, probably because they are rare, arrests for violent offenses were not assessed separately from overall arrests. Second, the duration of follow-up in these studies was relatively brief, thereby providing a smaller number of person-months of observation than would be considered ideal. Third, individuals posing the most serious violence risk were excluded from the randomized component of both studies for ethical and safety reasons.

A recent assessment of outpatient commitment in New York State (

10) also included an assessment of the effects of AOT on arrest (

11). The analysis involved samples of AOT clients and individuals receiving enhanced voluntary services in New York State. The study did not exclude people at high risk of violence and did include a longer follow-up to assemble 9,255 months of observation. Gilbert and colleagues (

11) found that overall arrests were significantly higher in the months before AOT than in the months during AOT. No statistically significant difference in arrest was found between the AOT group and the individuals who voluntarily accepted enhanced treatment.

We conducted a quasi-experimental study (N=183) that included individuals at high risk of violence and observed them over several years to yield 16,890 person-months of observation. Our study builds on the study by Gilbert and colleagues (

11) in three important ways. First, we included a group of patients who were recruited from the same clinics as the AOT patients but who had never received AOT. This group is important for understanding the effects of AOT because it enabled us to give an estimate of the risk of arrest in a group that was not deemed to be in need of AOT. It therefore provides a useful benchmark that allowed us to ask how closely the AOT group approached the risk level of this much-lower-risk group. Second, because sufficient events accrued over the long period of observation, our study allowed us to test the effect of AOT on violent offenses. Third, there were sufficient months of observation after AOT ended to provide an estimate of risk during that important period.

Discussion

Main findings

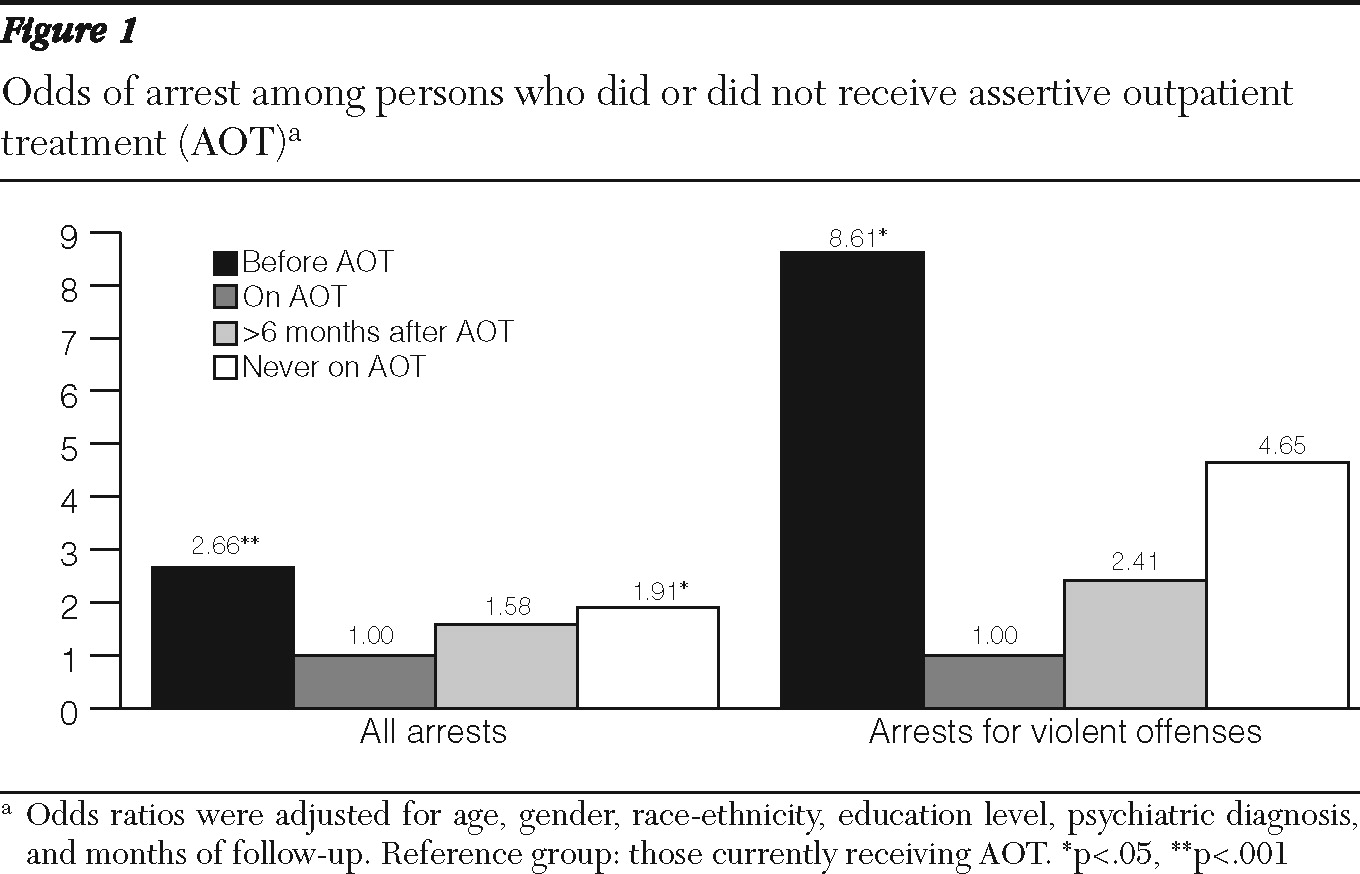

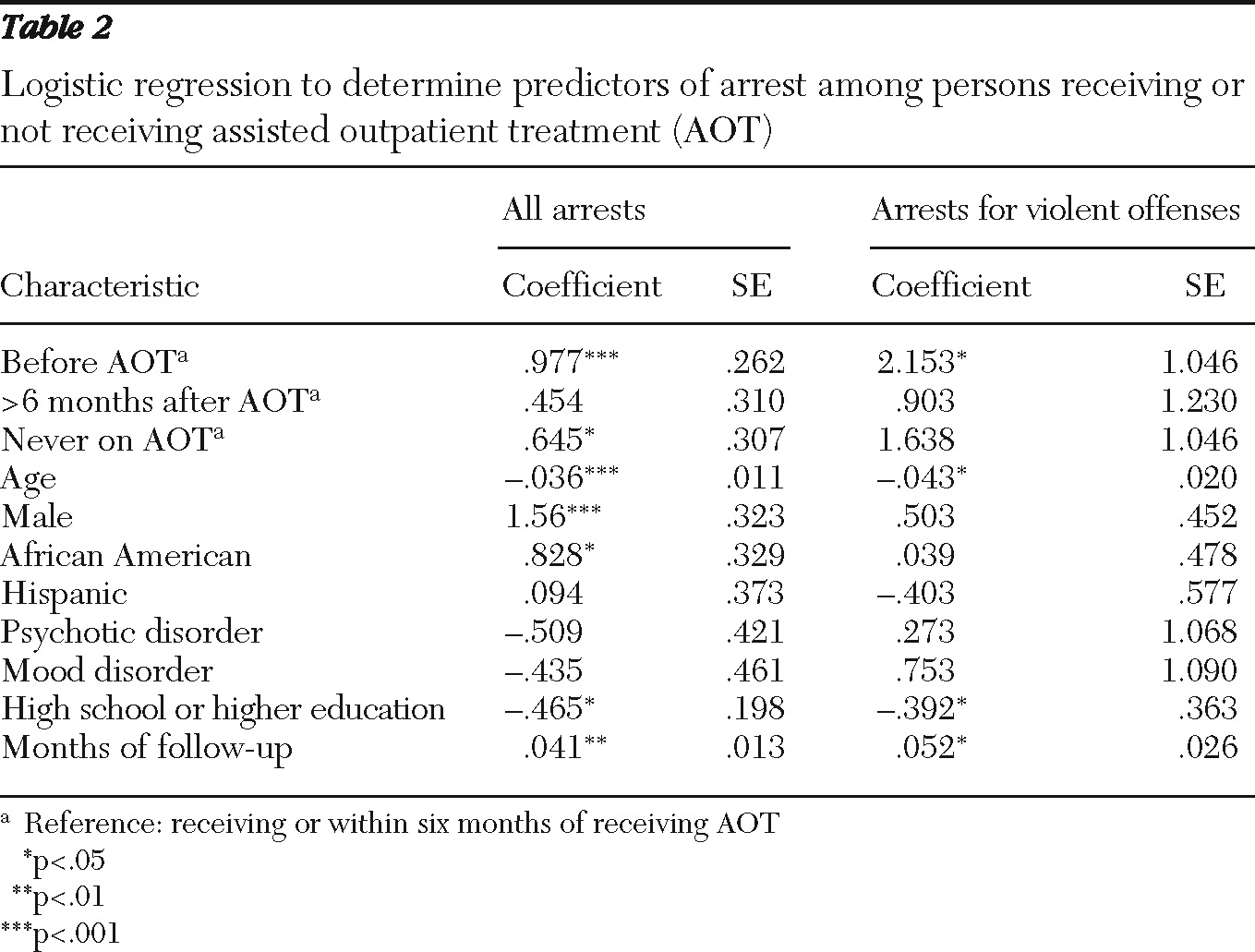

We found AOT to be associated with a sizeable reduction in the probability of arrest for both overall and violent offenses. Before assignment, individuals who would later be enrolled in AOT were substantially more likely than the same individuals while receiving AOT to experience arrest for both overall and violent offenses. In addition, we found that while individuals were enrolled in AOT the risk of arrest was actually lower than that of a comparison group of individuals never assigned to AOT and that the risk of arrest after AOT ended remained significantly lower than the risk in the period before AOT began.

AOT, as implemented under Kendra's Law in New York State, is a policy that substantially reduces the risk of arrest, including arrests for violent offenses among people with serious mental illnesses. From the vantage point of a general public concerned with violence and who hold prevalent perceptions of dangerousness concerning people with mental illnesses (

14,

15), this is a very positive and straightforward outcome: Kendra's Law directly results in reduced crime and violence. In addition, the result pushes us to consider a very beneficial trade-off in coercion, with a relatively small exposure under Kendra's Law forestalling a substantially larger exposure delivered by arrest. Our results can be read as an indication that both the general public and people assigned to AOT benefit—the former through a reduction in crime and violence and the latter through a reduction in experienced coercion and all of its untoward consequences.

The idea of a powerful mutual benefit, however, is complicated by the following considerations. First, a majority (53%), of the 86 study participants assigned to AOT were never arrested—not before, during, or after their assignment. It is, of course, possible that AOT forestalled some arrests during and after assignment of people who had never been arrested before assignment. At the same time, given that a majority of the AOT group was never arrested, it is likely that some people assigned to AOT were at extremely small or even no risk of arrest. For these individuals, there was no arrest reduction benefit to procure. It is also true that AOT strives to affect outcomes other than arrest, such as quality of life and reduction in self-harm, and previous research has shown benefits in these other domains (

2–

5). Still, in considering the trade-off in coercion, we must also consider that some people received the coercion of AOT without the possibility of a benefit in reduced coercion due to arrest. Second, although the coercion embodied in outpatient commitment is less severe than that involved in arrest, an important difference exists in the administration of the two forms of coercion. Arrest, at least in theory, is a specific response to a specific illegal action, whereas outpatient commitment is coercion administered to forestall events—illegal and otherwise—that might happen in the future. From a procedural justice point of view, the two types of coercion are quite different and might reasonably be experienced as such by individuals exposed to them (

16,

17).

Considerations concerning study validity

To minimize the influence of out-of-state arrests, we included as follow-up only months relatively close to a time when we knew the individual was living in New York (that is, at time of interview). In addition, we would expect coverage of arrests to be much better during AOT when the individual is mandated to treatment and known to be a New York State resident. As a result, any bias would be toward higher arrest rates during AOT than at other times, but we found just the opposite. Another consideration is that although outpatient clinics in New York City provided a good situation in which to test the effects of AOT, generalization to other populations should be made cautiously.

A strength of our quasi-experimental study is that it included individuals at risk of arrest for violent offenses and observed them for a period totaling more than 1,400 person-years. A limitation of our study is that it was not an experimental study with random assignment to study conditions. Yet the design, the analysis, and the pattern of achieved results increase confidence in our findings for the following reasons. First, one would expect the AOT group to have a greater risk of violence because selection into that group depends, in part, on the risk of violence and arrest. The finding that while participants received AOT their risk of arrest was lower than in the comparison group who had never received AOT runs counter to the bias one would expect in our quasi-experimental design. Second, our study provides results of within-group comparisons (before, during, and after AOT) that are not contaminated by biases associated with nonequivalence between groups. Finally, by controlling the effects of stable confounding variables, the fixed-effects analysis added a stringent test that provided concordant findings. Nevertheless, we caution that an ideal study would include both the analytic and design strengths of our study and random assignment to treatment conditions. As a result, we suggest that readers consider our findings in light of their deviation from such an ideal design.

Conclusions

Conclusions about the effectiveness of outpatient commitment as a policy cannot, of course, be based on results about arrest alone. With respect to this issue, studies have shown not only positive consequences but the absence of negative ones as well (

2–

4,

18). When considered in combination with these other studies, the conclusion about the effectiveness of outpatient commitment is generally positive, and in New York State, where this evaluation took place, the decision has been made to extend outpatient commitment. Still we end with a caution. So far, evaluations of outpatient commitment have occurred in the uptake of new policies when scrutiny of them by critics, policy makers, and the general public is intense. Waves of prior policy changes in public psychiatry have initially been met with enthusiasm and bold reports of effectiveness, only to later be deemed near total failures. In light of this history we need to be sure that the integrity of the enhanced services associated with outpatient commitment remains strong and that ongoing assessments of the policy are actively pursued.