Ample evidence demonstrates that the best practice standard for individuals with both a serious mental illness and a substance use disorder—otherwise known as co-occurring disorders—is an integrated approach in which mental health and substance abuse treatment is administered through one provider (

1). Many state and local mental health and substance abuse treatment organizations are moving toward integration through interagency relationships and agreements that vary in their intensity and formality. Individuals experiencing co-occurring disorders are frequently found in institutional settings such as jails (

2), yet criminal justice settings are infrequently part of an integrated approach. This omission is of particular concern to communities interested in improving service integration and collaboration across systems.

Individuals with co-occurring disorders are more likely to reoffend and to have poorer treatment outcomes and lower treatment retention rates compared with those with a single disorder (

3–

5). In addition, considering that criminal justice detention can compound psychological issues for individuals with mental illness (

6), it is essential not only to provide treatment to individuals while they are incarcerated but also to create transition plans linking them to services upon their release. Unfortunately, although transition planning is one of the most important mental health services, it remains one of the least frequently offered in prisons and jails (

7).

Because of the generally brief periods of confinement in jails compared with prisons, the planning period for the transition from jail to community is abbreviated, making it similar to that of hospital discharge planning. Frequently individuals are released from jail with a written referral to a community mental health provider and a limited supply of medication as a mechanism to promote transition into community-based treatment.

To examine how successfully this method of referral serves those with co-occurring disorders, this longitudinal study determined the proportion of incarceration episodes that were followed by transition to community mental health services. It also examined factors that predicted service engagement. This study is part of a broader investigation of countywide implementation of integrated services for those with co-occurring disorders (

8).

Methods

Administrative databases from county mental health and jail systems in Wayne County, Michigan, were merged. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was given to conduct a secondary analysis on the de-identified data. A total of 677 individuals met diagnostic criteria for both a substance use disorder and a serious mental illness and had had at least one jail episode during a 48-month period beginning in 2003. Information from mental health files was obtained from the data that are initiated for billing purposes at the time of service and included names of providers, types of services, and dates of services across the four years of the study. The county jail, which confines individuals for minor crimes and those awaiting trial, provided information on admissions, discharges, and offense types for the 48-month period. The two data sets were merged to produce case-wise files organized by individual.

Diagnoses were determined by community mental health professionals, either in the jail or in the community, as part of a service eligibility screen and were reported by both mental illness and type of substance use disorder, either abuse or dependence. The dependent variable, treatment engagement, was modeled as an indicator variable based upon the presence or absence of any service, such as medication review, case management, and group therapy, provided in the community through the publicly funded county mental health system.

To determine which factors predicted engagement with mental health services upon release from jail, an analysis was performed using the jail episode as the unit of analysis. Because some individuals experienced multiple jail episodes during the study period, a logistic regression was used to control for the possibility that postincarceration service engagement was correlated by individual over time. A logistic regression was therefore fit to the data using a generalized estimating equation (GEE), clustered on individuals.

Results

The mean±SD age of the sample was 37.0±9.8 years, with a range of 18 to 68 years. The sample was predominantly male (N=452, 67%); 37% (N=253) were African American, and 34% (N=228) were European American. Information about race-ethnicity was missing in 187 cases (28%). A high proportion of the sample had been given a diagnosis of depressive disorder not otherwise specified (N=305, 45%); smaller proportions received diagnoses of schizophrenia (N=166, 24%), bipolar disorder (N=153, 23%), and major depressive disorder (N=53, 8%). Most (90%) had the more severe co-occurring diagnosis of substance dependence (N=608) rather than abuse (N=69). [A table reporting the demographic characteristics and co-occurring diagnoses for the sample is available in an online appendix to this report at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

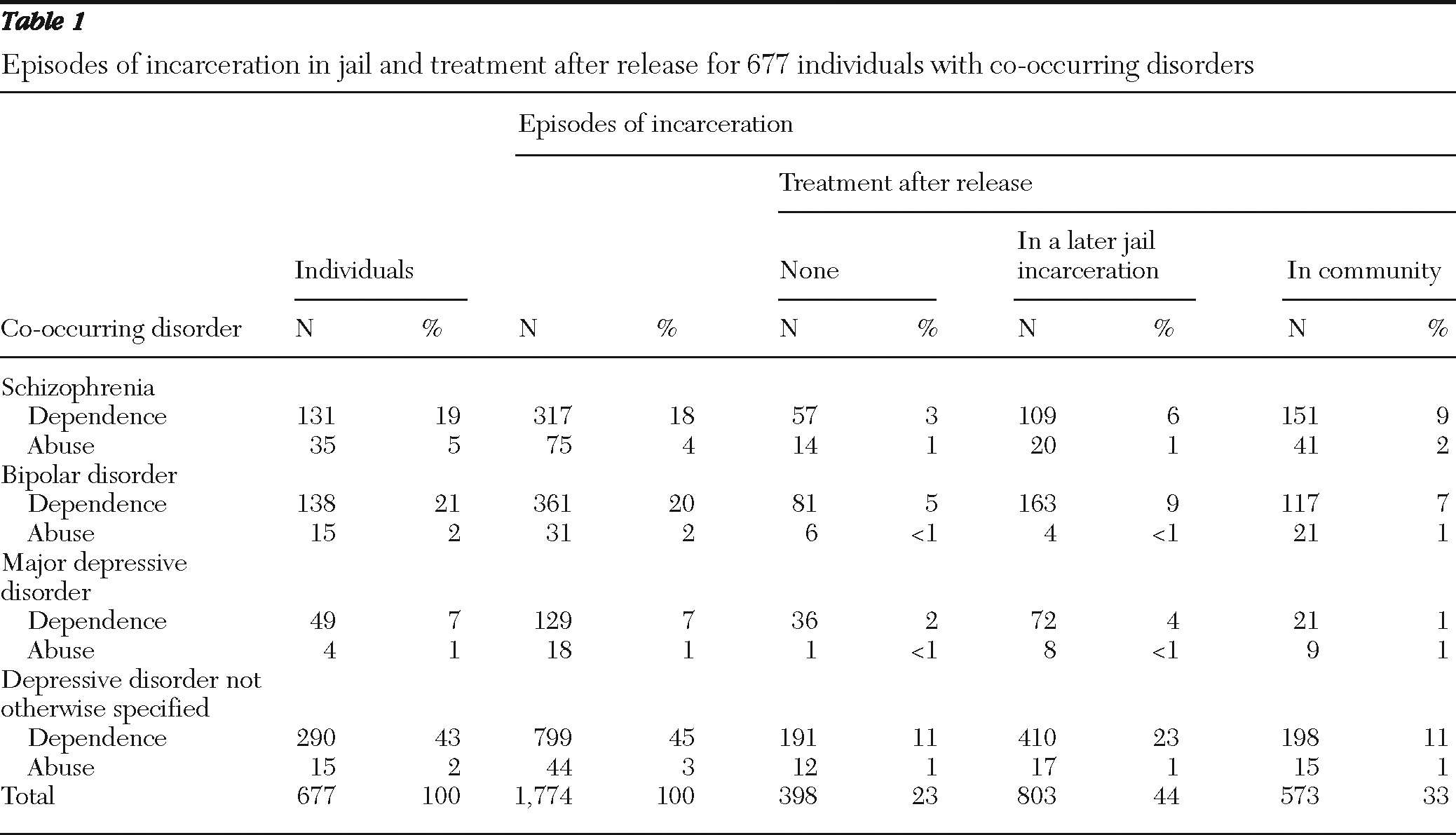

There were 1,774 episodes of incarceration for the 677 individuals, with a mean±SD number of episodes of 2.6±2.2 and a range of one to 14 episodes per person across 48 months. The mean number of days spent in jail was 37.2±50.5; 821 episodes (46%) lasted 14 days or fewer.

Table 1 shows engagement in community-based mental health treatment after release from jail for individuals with various co-occurring disorders. Overall, in 398 of the 1,774 jail episodes (23%), individuals did not receive mental health services either in the community or during a subsequent jail stay. In 803 jail episodes (44%), individuals received their next mental health service during their next jail stay as opposed to while living in the community. In the remaining 573 episodes of incarceration (33%), at least one mental health service was provided to individuals in the community irrespective of whether they eventually returned to jail.

Logistic regression determining factors that predicted treatment engagement revealed significant differences by diagnoses (see the online table at

ps.psychiatryonline.org). Compared with individuals with schizophrenia and substance dependence—the reference group—individuals with bipolar disorder and substance dependence were less likely to obtain services in the community after release from jail (odds ratio [OR]=.51, 95% confidence interval [CI]= .33–.79), as were individuals with substance dependence and either major depressive disorder (OR=.21, CI=.11–.39) or depressive disorder not otherwise specified (OR=.35, CI=.24–.52). There were no differences in treatment attainment between the reference group and individuals with a diagnosis of substance abuse in any psychiatric diagnostic group. Women were more likely than men to obtain community-based mental health services after release from jail (OR=1.37, CI=1.02–1.83). Age was not predictive of treatment engagement.

Discussion and conclusions

This study examined the transitions between the county jail and community mental health services for individuals with co-occurring disorders and factors that might predict treatment engagement. Our analysis revealed that in only one-third of the 1,774 jail episodes did the expected transition to community-based treatment occur. In fact, across diagnostic categories, and controlling for the lack of independence in jail episodes, we found that in the majority of cases, individuals never engaged in community treatment and were far more likely to receive their next treatment service in the jail.

Barriers to successful transition are likely to include both individual and system factors (

9). The presence of a more serious substance use disorder—corresponding perhaps with low motivation for treatment—is an individual barrier (

10,

11). However, the robustness of substance use disorder as a predictor of unsuccessful transitions suggests that failure to engage these individuals is also a system barrier (

12). Integrated treatment for co-occurring disorders has been described as “a rubric for sensible structural arrangements to ensure access rather than a specific intervention” (

13). It has been successful with criminal justice clients as both an intervention (

14) and a structural approach (

15). However, the first step in ensuring successful treatment outcomes is engagement in treatment.

The strength of this study was its longitudinal nature (lasting four years) and its use of GEE analysis, which clustered on individuals when analyzing transitions, thereby holding individual differences constant when the possibility of multiple incarcerations per person was considered. In addition, because the county mental health system is the primary provider for individuals with serious mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders, we were able to assess practices “as usual” for an entire countywide system. Certainly there are limitations in using administrative data. The transient nature of the population may have resulted in obtaining services in another county or from a private provider. However, our reliance on the county mental health database as the initial source of study eligibility demonstrates the individual's affiliation with the county's publicly funded system.

Incarcerations may disrupt community supports, treatment, and medication regimen. Alternately, jail may be a catalyst for engagement in treatment—for example, through mental health courts or diversion programs. Whichever the scenario, collaboration between and within community mental health providers and jails, including the cross-training of staff on issues related to community reentry and the brokering of services before discharge, is paramount to ensuring access to integrated treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Funding for this project was made possible with a grant from the Detroit-Wayne County Community Mental Health Agency (DWCCMHA) for the purpose of improving service delivery and adoption of evidence-based practices within the geographic region. The authors thank both DWCCMHA and Wayne County Jail for their assistance and cooperation.

The authors report no competing interests.