Approximately 12.3 million disadvantaged Americans are enrolled in both Medicare and Medicaid (

1). Individuals with dual Medicare and Medicaid coverage are considered among the most vulnerable patients with the most complex conditions in the U.S. health care system (

2–

5). Approximately 30% have a serious mental illness, nearly three times the prevalence among other Medicare enrollees (

4). As of 2019, individuals with dual coverage constituted 17% of Medicaid enrollees but accounted for $300 billion or 32% of annual Medicaid spending (

6). That Medicare and Medicaid operate as separate health benefit programs is recognized to impede care coordination in this group and to result in redundant and inconsistent care and higher health care expenses (

2–

5). For example, each program has its own enrollment process, benefits package, provider networks, and medical cards. This lack of integration can have an outsized negative impact on individuals with complex mental health conditions, who typically utilize various types of services providing acute and ambulatory specialty mental health care and who have multiple prescription medications.

In 2003, to improve alignment and integration between Medicare and Medicaid and to better coordinate access to services, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) introduced private Medicare Advantage (MA) Dual Eligible Special Needs Plans (D-SNPs). D-SNPs have been in operation since 2006; as of 2021, these plans had >3 million enrollees, or approximately 26% of all individuals with dual coverage across 43 U.S. states and the District of Columbia (

7). As managed care has grown to become the predominant type of insurance in Medicaid (

8), state Medicaid agencies are increasingly aligning enrollment in Medicaid managed care plans with enrollment in an affiliated MA D-SNP offered by the same managed care organization (MCO) (

9). In some states, enrollment in a D-SNP occurs automatically when individuals with Medicaid qualify for Medicare (

9).

Rapid D-SNP enrollment growth (

7) offers an opportunity to address long-standing health care access and coordination challenges between Medicare and Medicaid for adults with serious mental illness (

10,

11). Compared with enrollment in other MA plans and other Medicaid managed care plans, enrollment in a D-SNP may offer individuals with serious mental illness access to benefits tailored to their specialized care needs. For example, D-SNPs are designed to integrate the administration of Medicare and Medicaid benefits, which may protect enrollees with mental illness from improper Medicare billing of copayments. Also, D-SNPs generally cover specialized care management and coordination services (

12), such as peer provider services and intensive case management, that may not be available in other types of plans.

In this study, we compared psychiatrist provider networks in D-SNPs with psychiatrist networks in other MA plans. The design of specific provider networks is a critical feature of D-SNPs that has received limited attention in previous research (

13,

14). Most individuals with serious mental illness take psychiatric medications (

15) and require a convenient usual source of specialty mental health care (

15). In contrast to traditional Medicare and fee-for-service Medicaid plans, MA plans manage care via a network of participating providers. Because D-SNPs enroll a disproportionate share of individuals with serious mental illness (

4), who typically require access to a usual source of specialty mental health care and may benefit from care coordination (

16–

18), we hypothesized that provider networks of D-SNPs include a greater fraction of a service area’s psychiatrists, compared with the provider networks of other MA plans. We tested this hypothesis by comparing psychiatrist versus nonpsychiatrist network breadth between D-SNPs and other MA plans.

Methods

The Johns Hopkins University Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol, which included a waiver of consent and a HIPAA waiver. Study analyses were conducted between August 2021 and March 2022.

Data and Sample

Data sources.

Publicly available CMS databases covering all MA plans active in August 2019 were used to identify plan numbers, names, enrollment totals, counties served, and other plan and contract information (

12,

19). Counties within a plan’s service area that had no or <11 enrollees were not included in the analysis. The CMS plan data were merged with the 2019–2020 Vericred provider networks data (

20) to identify plans’ provider networks. Providers listed in networks were in turn linked with provider characteristics from OneKey (

21), a commercial database that includes essentially all health care providers nationwide in 2019, except for providers in armed forces hospitals. OneKey nonpediatrician physicians who accepted Medicare, were born after 1939, had an active National Provider Identifier number, and practiced at an office, hospital, or residential facility were retained. According to a Kaiser Family Foundation analysis (

22), 99% of active nonpediatrician physicians accepted Medicare in 2020. Of the physician records that met inclusion criteria, 0.7% were missing year of birth, and thus the individuals might have been born before 1940. The Vericred database was developed by compiling plans’ provider directories. Although Vericred’s 2019 provider networks database was used first, the 2020 database information was used for observations (N=45) from plans first reported in the 2020 networks database. The Vericred provider networks included 95.0% of physicians listed in OneKey who met our inclusion criteria.

Sample exclusions.

Before exclusions, the sample contained 1,552 observations on networks subclassified by state and network type (network-state-type observations). Of these, 263 observations were from D-SNPs and 1,289 were from other MA plans. A total of 116 other MA observations from the eight states that did not have any D-SNPs in 2019 (Alaska, Illinois, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Dakota, South Dakota, Vermont, and Wyoming) were excluded, leaving 1,436 observations. An additional 300 plans that could not be matched to a network or that matched networks that had no providers listed were then dropped, leaving 1,136 plan-network observations (229 D-SNPs and 907 other MA plans).

Network breadth.

The same network serves multiple plans. Plans that shared the same provider network were grouped by state and plan type (D-SNP or other MA plan) to create a network-state-type unit of analysis. In instances in which plan enrollment spanned more than one state, the plan was split into separate plan-state observations. Providers were initially grouped into nine specialty categories: dermatology, hospitalist, neurology, internal medicine, obstetrics-gynecology, primary care, psychiatry, surgery, and other. Preliminary analyses showed no significant differences in mean network breadth between primary care and every other specialty category—except psychiatry, for which the mean breadth estimate was significantly smaller than for all other specialties. Consequently, all nonpsychiatrist specialties were combined to create separate measures of psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist provider network breadth. Provider network breadth was calculated within each individual grouping of network, state, and plan type as the in-network fraction of providers in the combined plans’ service areas (i.e., counties with ≥10 enrollees and at least one qualifying provider of each type).

During data checks, some network-state-type observations were found to have psychiatrist network breadth values unusually close to zero (<2%) or an extremely high ratio of nonpsychiatrist-to-psychiatrist breadth (≥4). During further investigation, we found that some known behavioral health provider networks were not present in the Vericred networks data set. Most of the extreme values were for a single nationwide managed care provider that offers behavioral health services under a separate network. To limit potential bias from incomplete behavioral health network information, 293 additional network-state-type observations (44 D-SNPs and 249 other MA plans) with breadth <2.0% for psychiatrist or nonpsychiatrist providers or a ratio of nonpsychiatrist-to-psychiatrist breadth ≥4 were removed from the analysis. This left a final sample of 843 observations from 42 states and Washington, D.C. We conducted sensitivity analyses in which we set minimum breadth at 1.5%, 3%, and 5% and the ratio of nonpsychiatrist-to-psychiatrist breadth at 3 and 3.5. The chosen thresholds were not sensitive to these alternative choices.

Using the psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist breadth measures, a third measure, the difference between psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist network breadth within the same network, state, and plan type, was created. A negative psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist difference implies that psychiatrist provider networks are narrower (i.e., less inclusive of a service area’s providers) than nonpsychiatrist networks within the same network, state, and plan type. One advantage of this difference measure is that it cancels out variations in network breadth that are common to psychiatrists and nonpsychiatrists within the same network and state. For example, both psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist network breadths might be lower in states with greater population density and more psychiatrists. By taking the difference between psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist breadth, such sources of variation that are common to both provider types are removed, which helps isolate the residual psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist differences within states, networks, and plan types.

Analyses

Analyses were performed in Stata, version 17. First, we mapped the share of individuals with dual coverage who enrolled in D-SNPs at the county level. We then used F tests to examine whether the mean of psychiatrist network breadth differed from the mean of nonpsychiatrist provider network breadth in each plan type. Medians and the 25th and 75th percentiles are also reported. Finally, using the mixed procedure, we estimated a mixed regression model for the three dependent variables, psychiatrist network breadth, nonpsychiatrist network breadth, and the difference between psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist network breadth (psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist breadth difference). Random state intercepts were used to adjust for the influence of common state-level sources of variation (e.g., the number of psychiatrists per capita).

Results

D-SNP Penetration

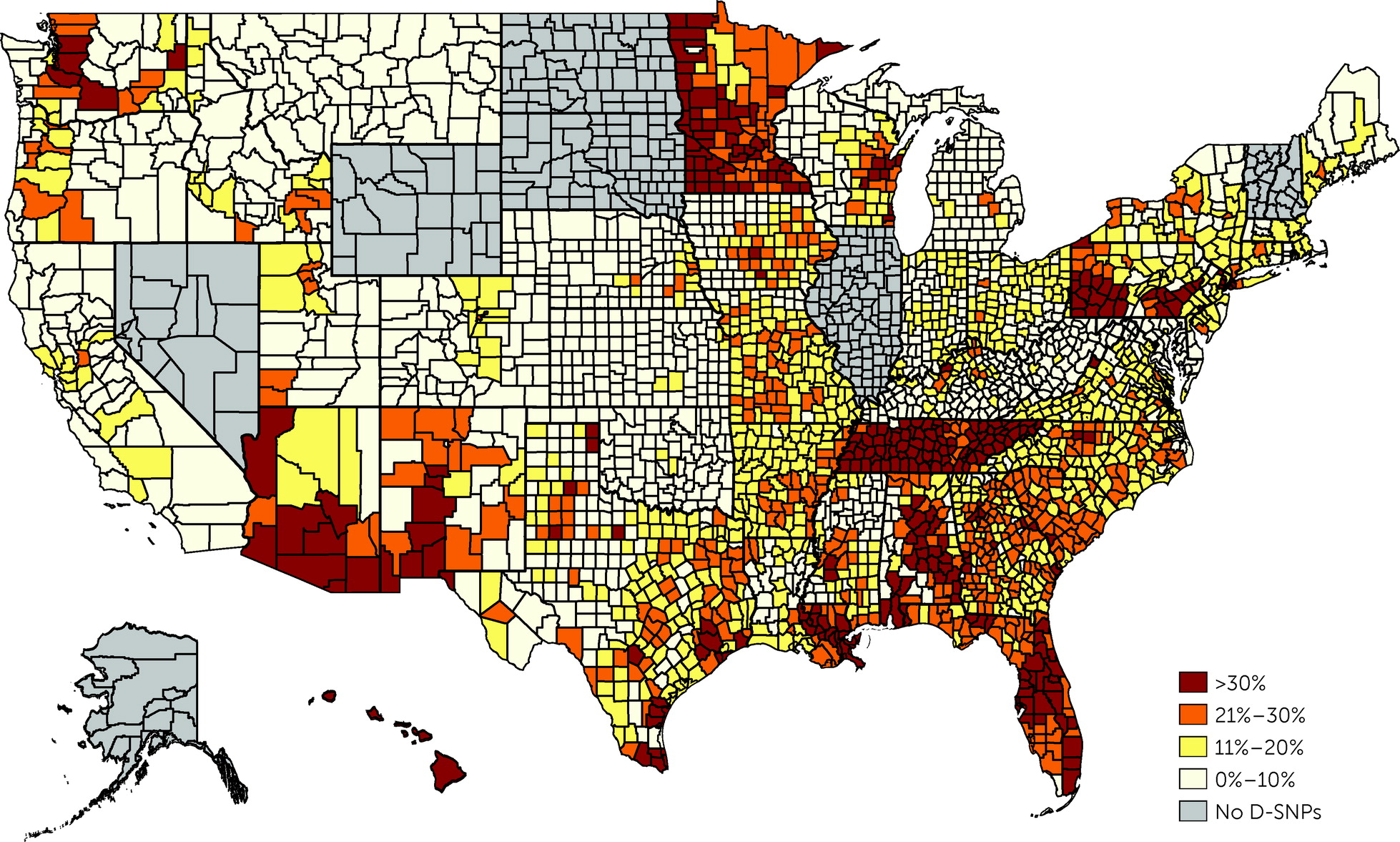

Figure 1 shows a county-level map of D-SNP enrollment prevalence as a fraction of the total number of individuals dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid in each county. D-SNP shares varied both at the state and the county levels. D-SNPs in eight states—Alabama, Arizona, Florida, Hawaii, Minnesota, New York, Pennsylvania, and Tennessee—had at least 30% shares, compared with 15% among D-SNPs nationwide. D-SNP enrollment was also strong throughout the South and in scattered urban areas.

Mean Network Breadth

Overall, the mean of network breadth was 0.303 for psychiatrist networks and 0.355 for nonpsychiatrist networks (

Table 1), a mean difference of −0.052 (p<0.001). The corresponding medians (and 25th–75th percentiles) were 0.284 (0.163–0.430) for psychiatrists and 0.355 (0.223–0.482) for nonpsychiatrists. Psychiatrist network breadth did not differ significantly between D-SNPs (0.319) and other MA plans (0.299) (mean difference=0.020, 95% CI=−0.016 to 0.056), and nonpsychiatrist breadth also did not differ by plan type (0.346 in D-SNPs vs. 0.358 in other MA plans; mean difference=0.012).

Mean network breadth was on average smaller for psychiatrists than for nonpsychiatrists, regardless of plan type. The mean psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist network breadth difference was −0.031 in D-SNPs, compared with −0.060 in other MA plans (p=0.002) (

Table 2).

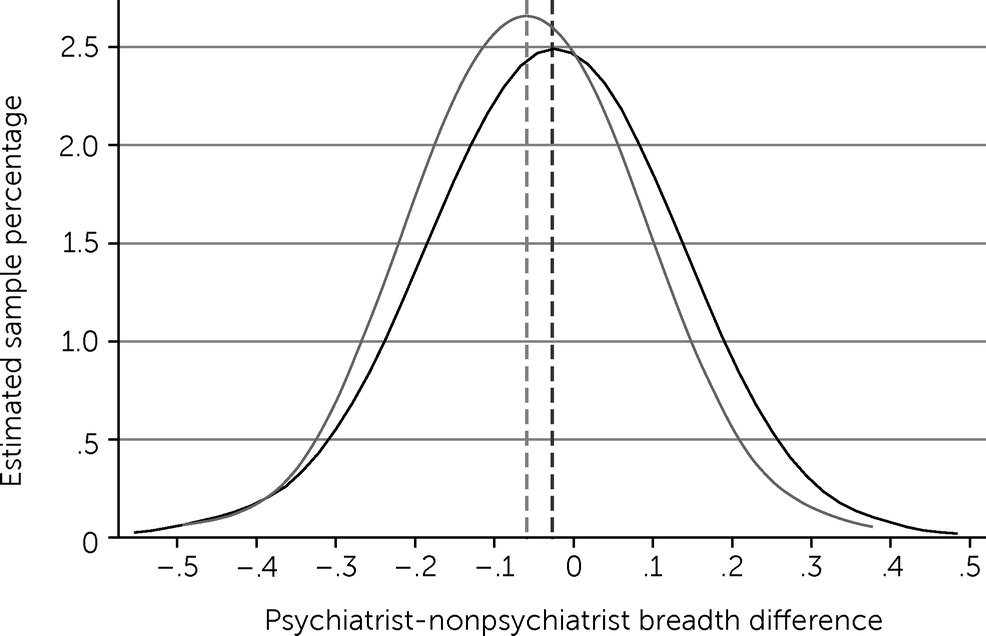

Figure 2 shows the probability density for the psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist breadth differences by plan type (Epanechnikov kernel, bandwidth=0.05). The y-axis indicates sample percentages, and the x-axis shows values for the psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist breadth difference (0=no difference). The −0.032 mean difference between D-SNP and other MA plan networks was small relative to the overall sample variability in psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist breadth differences shown in the figure.

Relationship With Psychiatrist Concentration

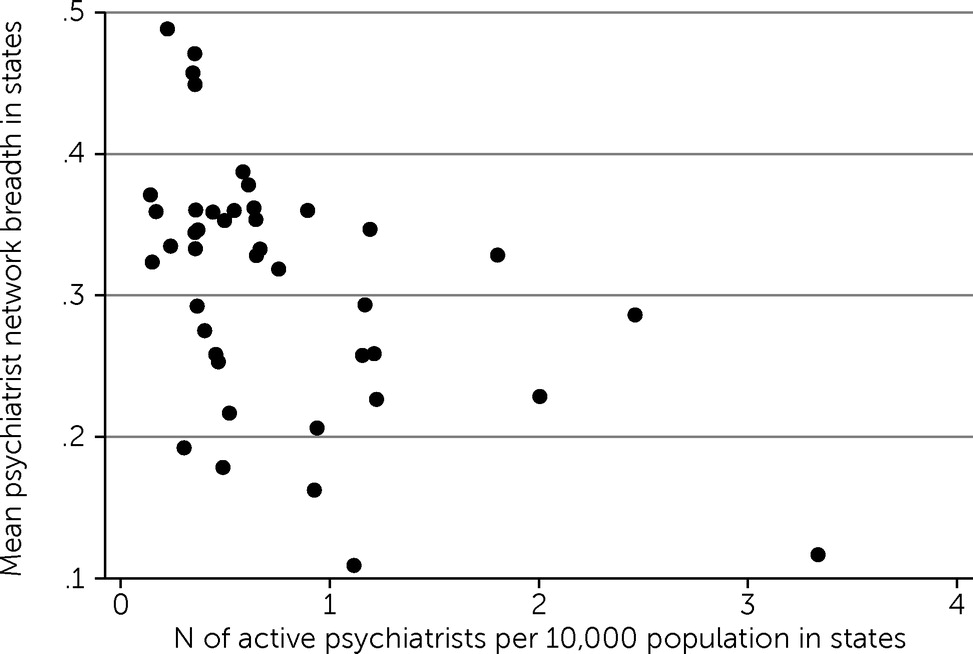

Figure 3 shows a plot of mean psychiatrist network breadth in D-SNPs in each state by the number of active psychiatrists per 10,000 population in each state from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (

23). State population totals for April 2020 were obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau (

24). We observed a statistically significant negative correlation between these two variables (Pearson correlation coefficient=−0.489, p<0.001), indicating that mean psychiatrist network breadth tended to be smaller in states with more psychiatrists per capita.

Regression-Adjusted Estimates

In mixed-model regressions, we observed no significant differences in psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist network breadth between D-SNPs and other MA plans (

Table 2). However, the adjusted psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist breadth difference was smaller in D-SNPs by 0.029 or 48.3% (95% CI=−78.5% to −18.1%), compared with other MA plans.

Discussion

We found that D-SNPs, which are MA plans designed specifically for adults who are dually enrolled in Medicaid and Medicare, differed little from other MA plans in the breadth of their psychiatrist provider networks. The mean of psychiatrist network breadth was 0.319 in D-SNPs and 0.299 in other MA plans, a nonsignificant difference of only 0.020. This level of difference was small compared with the overall variance in psychiatrist network breadth among networks and states. For example, the middle 50% of observations had psychiatrist network breadth values between 0.164 and 0.430. Consequently, psychiatrist networks in D-SNPs were found to be on average similar in breadth to those in other MA plans.

CMS currently sets network adequacy requirements for all MA plans but does not specify separate network adequacy requirements for D-SNPs (

25). During the study period, CMS required that MA organizations contract with enough providers and facilities so that 90% of enrollees in a county reside within the maximum allowed time and distance of at least one provider representing each of 27 provider types, of which psychiatry is one. According to a 2015 U.S. Government Accountability Office report, CMS network adequacy requirements for MA plans are minimal and inconsistently enforced (

26). A report of the 2019 Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation on D-SNP networks based on interviews with state Medicaid officials also highlighted gaps in minimum adequacy criteria of CMS networks for provider networks and recommended that network adequacy criteria be applied at the D-SNP level rather than at the MA contract level (

11), because many MA contracts encompass both D-SNPs and other MA plans. This study provides further evidence that such a delineation might be necessary to align network adequacy criteria with the special purpose of D-SNPs and the special population they serve.

Mean breadth was found to be narrower in psychiatrist networks than in nonpsychiatrist networks (0.303 vs. 0.355), with a mean psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist difference of −0.052. A similar disparity between behavioral health and primary care providers was previously reported by Zhu and colleagues (

27) for U.S. marketplace plans. The only other related published estimate of breadth is from a study of clinically active psychiatrists in Massachusetts in 2013, which found that 33% of psychiatrists participated in MA plans (

28); that estimate was not compared with those from other physician specialties. Disparities between psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist network breadths in MA plans might reflect a combination of psychiatrist supply factors as well as managed care policies and strategies (

29). A nationwide study of MA plans found that mental health service providers received lower reimbursement amounts than did nonpsychiatrist providers providing the same services (

29), and MA plan reimbursements were lower than those in traditional Medicare. Some psychiatrists may also elect not to participate in D-SNPs because of nonfinancial costs associated with providing care for individuals with more severe mental health problems and symptoms. Compared with other physician specialties, psychiatrists are generally less likely to participate in plans that serve Medicaid enrollees (

30), which may reflect a combination of financial disincentives from lower reimbursement and nonfinancial factors stemming from the greater complexity and severity of mental illness among Medicaid enrollees. In fact, a 2017 Kaiser Family Foundation survey found that state Medicaid managed care plans had more challenges recruiting specialist providers into their networks than recruiting primary care providers, despite direct outreach, financial incentives, and prompt payment (

31).

The finding of an inverse relationship between psychiatrist network breadth and the number of psychiatrists per capita in states suggests that MA organizations are more selective when choosing in-network psychiatrists in regions where psychiatrists are more concentrated. Plans may limit network size in such regions to obtain better contract terms from providers and to hold down plan premiums (

14). By contrast, in regions where psychiatrists are scarce, MCOs might have to be comparatively more inclusive of providers to adequately serve plan members or to meet CMS network adequacy requirements.

Finally, the finding that the psychiatrist-nonpsychiatrist breadth difference was 48.3% smaller in D-SNP networks, compared with other MA plan networks, suggests that D-SNPs may offer somewhat improved parity in network breadth between behavioral health and other types of health care. Although parity legislation under the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 and the Affordable Care Act of 2010 requires similar health insurance coverage terms and beneficiary copays for behavioral health services as for other types of care, similar parity standards are not currently applied to provider networks in managed care plans (

27), which use networks and utilization review rather than enrollee cost-sharing provisions to manage utilization and costs. Financial incentives for utilization control in capitated MA plans may consequently result in some carriers selecting relatively narrow psychiatrist networks to obtain provider price discounts or to hold down plan costs and premiums. Consequently, the parity concept that already applies to coverage amounts and enrollee cost-sharing in U.S. health insurance plans could be extended to apply to parity in psychiatrist networks, compared with networks for other provider types. To our knowledge, this broader conceptualization of behavioral health parity in practice has not yet been mentioned in policy discussions of managed care provider networks.

This study had some limitations. It offers only an initial, partial view of behavioral health network adequacy in D-SNPs. The study addressed what MA organizations offer in terms of provider networks, which is the supplier side of the MA market. The study did not address consumer need for and access to behavioral health providers. Additional information regarding, for example, whether in-network providers accept new Medicare or Medicaid patients or the average time until an appointment is available is needed to form a more complete picture of MA network adequacy for behavioral health. In 2014–2015, only 35% of psychiatrists were accepting new Medicaid patients (

32,

33). The study also focused on psychiatrists alone and did not include data on psychologists, social workers, nurses, and other providers of specialty mental health care. Although we would expect network breadth for these other providers to be correlated with network breadth for psychiatrists, measures of network breadth for other mental health providers were not available.

Conclusions

The breadths of psychiatrist and nonpsychiatrist provider networks in D-SNPs were found to be similar to the breadth in other MA plans that are not specially reserved for adults who are dually enrolled in Medicare and Medicaid. In addition, psychiatrist networks were on average narrower than nonpsychiatrist networks regardless of plan type, and networks that served regions with more psychiatrists tended to be narrower than networks serving regions with fewer psychiatrists. Further application of the psychiatrist measurement approach used in this study could help inform the development of psychiatrist network adequacy criteria for MA D-SNPs.