Increasingly, personality disorder researchers are suggesting the relevance of dimensional models of personality diagnosis

(1,

2) . Virtually all of these models are trait models, derived from the factor analysis of self-report data. Recently, our group

(3) described a trait model of personality pathology derived from the Shedler-Westen Assessment Procedure-200 (SWAP-200), a 200-item Q-sort procedure for assessing personality pathology

(4) . The SWAP-200 differs from other personality and personality disorder instruments in that it was designed for use by clinically experienced informants. Factor analysis of the SWAP-200 yielded 12 factors (e.g., psychological health, psychopathy, hostility, narcissism, emotional dysregulation, dysphoria)

(3) .

A long history of research questions whether clinicians can reliably diagnose personality or other forms of psychopathology (e.g., references

5,

6) . However, recent studies using the SWAP-200 suggest that clinicians can indeed make reliable and valid diagnostic judgments if their judgments are quantified with psychometric instruments comparable to those previously developed for self-reports

(7 –

10) . Studies to date have assessed the reliability and validity of SWAP personality disorder diagnoses, using either current axis II diagnoses or diagnoses derived empirically using Q-factor analysis

(11,

12) . The aim of the present study was to assess the interrater reliability and validity (cross-informant correlations between the treating clinician and independent interviewers) of the 12 SWAP-200 trait scale scores derived by factor analysis

(3), which are more comparable to trait dimensions assessed by self-report measures.

Method

The group of 24 outpatients has been described elsewhere

(8) and will be described only briefly here. The patients were interviewed by clinically experienced interviewers who were blind to all data about the patient using the Clinical Diagnostic Interview

(13), a systematic clinical interview designed to systematize the kind of interviewing experienced clinicians use in practice (e.g., eliciting narratives about patients’ symptoms and life histories and focusing on specific examples of emotionally salient experiences). Interviews were videotaped so that a second clinician/judge could blindly evaluate the patient for interrater reliability. Treating clinicians (N=16) who were blind to all interview data also independently provided a SWAP-200 description based on their clinical experience with the patient, providing a form of validity evidence (cross-informant agreement). The treating clinicians received no training on the SWAP-200 and ranged from fourth-year residents to experienced clinicians.

Results

The study group consisted of 16 women and eight men, ranging from age 19 to 57 years, with a mean age of 38.6 years (SD=10.5). The group was diverse in both axis I and II symptom profiles (see reference

8 ). Primary axis I diagnoses included major depressive disorder, dysthymic disorder, adjustment disorder, panic disorder, substance use disorder, eating disorder not otherwise specified, dissociative disorder not otherwise specified, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Axis II diagnoses included borderline, dependent, antisocial, avoidant, and narcissistic personality disorders; more than one-third had personality disorder not otherwise specified.

With respect to interrater reliability, the median correlation (Pearson’s r) between the two interview judges was 0.82 (range=0.45 to 0.89). The only values below 0.70 were for the last three factors, which have the fewest items and, hence, the lowest internal consistency.

With respect to validity,

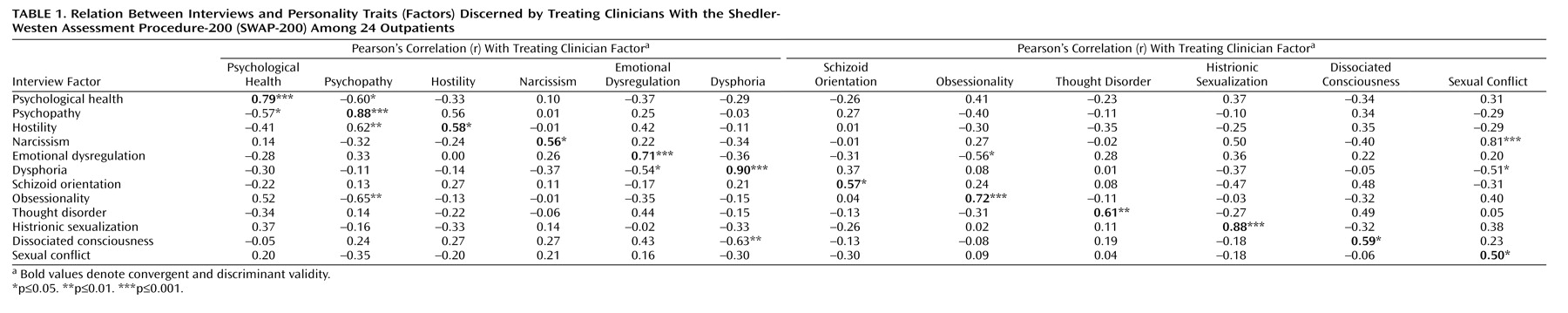

Table 1 reports cross-informant correlations for each factor, between the mean of the two clinician/judges using the Clinical Diagnostic Interview (aggregated to maximize reliability) and the treating clinician. The data provide strong evidence for convergent and discriminant validity, with a median coefficient on the diagonal (convergent validity) of r=0.66 and a median correlation off the diagonal (discriminant validity) of r= –0.06. With few exceptions, ratings on the diagonal were substantially higher than ratings off the diagonal, even though one set of scores came from a 3-hour interview and the other from clinicians’ longitudinal observations of the patient.

To index more formally the degree of congruence between interview and clinician scale scores, we used a procedure that applies contrast analysis to correlation coefficients to provide an overall index of the extent to which obtained findings matched predictions

(14,

15) . The procedure yields a Pearson’s correlation (called r

contrast for construct validity or, simply, r

contrast-CV ) as an overall estimate of the effect size, which is interpreted just as r is interpreted in other contexts as an estimate of effect size. For each scale, we employed a stringent test, predicting correlations along the diagonal close to 0.80 and correlations off the diagonal of 0.0 (using contrast weights of 11 and –1, respectively, with 11 off-diagonal coefficients; contrast weights must total 0). Coefficients ranged from 0.50 to 0.96, with a median r=0.68, indicating large effect sizes, all significant at p<0.001. The significance values are particularly noteworthy given the small group size.

Discussion

The data provide further evidence for the interrater reliability and cross-informant convergence of clinical personality judgments with the SWAP-200 and suggest that clinically experienced observers can, in fact, make reliable and valid judgments regarding complex, clinically meaningful personality traits using psychometric instruments designed for this purpose. The data also suggest that clinically experienced observers can make reliable and valid judgments using a systematic clinical research interview (the Clinical Diagnostic Interview) that standardizes and systematizes clinical interviewing procedures that are the norm in clinical practice

(13) but that have widely been assumed to be unable to yield reliable and valid data. In fact, not only are the interrater reliabilities reported here (particularly for the first nine scales, which have an adequate number of items per scale) adequate to good, but the cross-informant correlations are larger than any personality or personality disorder measure of which we are aware. For example, the most widely studied self-report inventories assessing the five-factor model yielded correlations between informants who know each other well (e.g., spouses), ranging from 0.30 to 0.60, with a median hovering around 0.40

(16) . The results of this study also suggest the potential utility of the construct validity metrics used here.

The study has two primary limitations. First, as in most psychiatric interview research, the two interview judges coded the same interview data rather than each performing independent interviews (although the high correlations with treating clinician judgments render this limitation less important). Second, the group was small, although the effects were large, and the contrast analyses—which take the number of subjects into account—were significant. Clearly, however, the next step in this research is to collect data on a larger, broader sample of patients with not only the SWAP-200 but other personality disorder instruments widely in use to assess their relative ability to predict a range of criterion variables.