Mood disorders are familial

(1,

2) . Twin studies have demonstrated a role for genetic and environmental factors

(3 –

5), but limited progress has been made in identifying the responsible genes. To date, linkage studies have not replicated vulnerability genes for major depression

(6), perhaps because larger samples are required to detect small effects of individual genes on complex behavioral traits

(7) . Case/control association studies of candidate genes have produced mixed results

(6) . Gene/environment

interactions also contribute to the etiology of mood disorders

(6) .

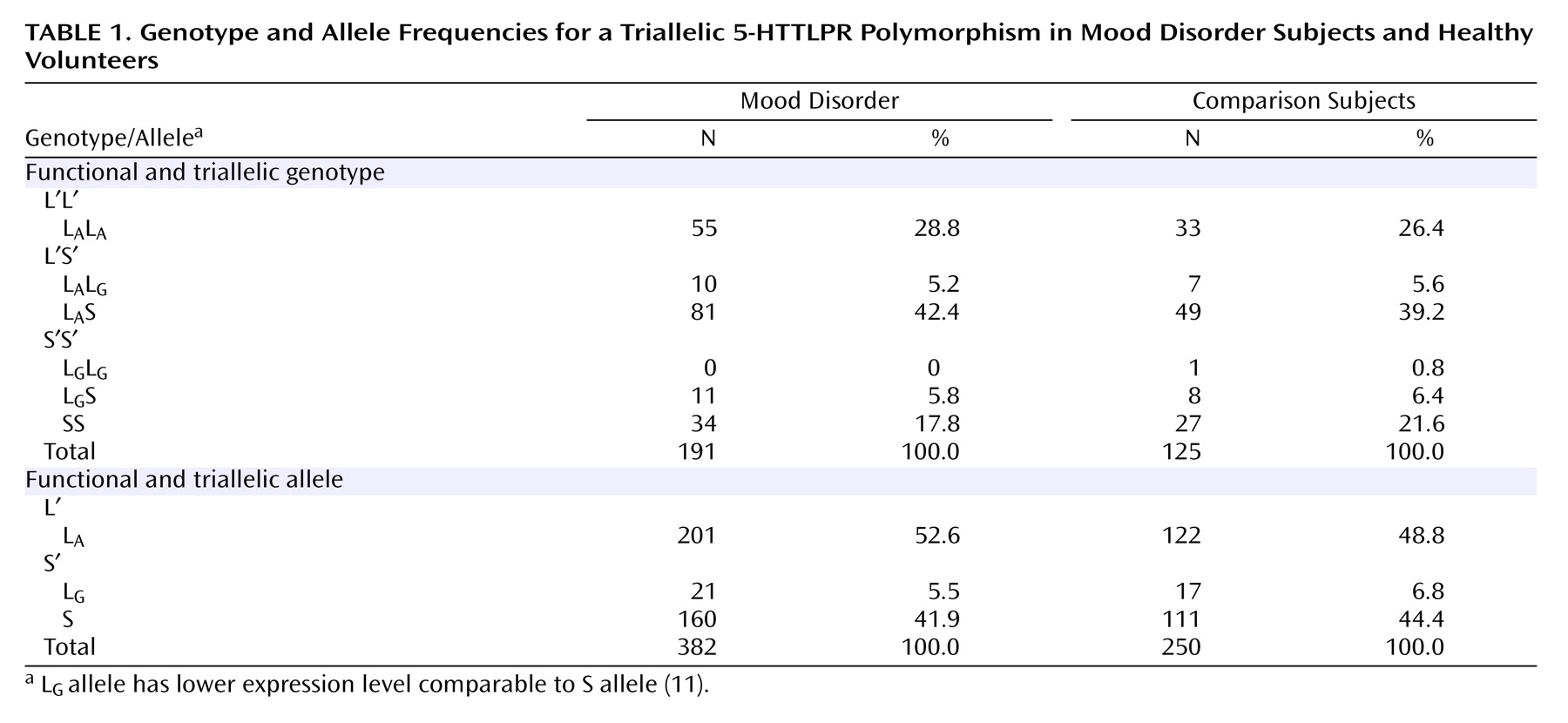

Other 5-HTTLPR variants, particularly in Japanese individuals, are rare in Caucasians

(10) . A third functional allele, L

G, has been described with an A>G polymorphism at position 6 of the first of two 22-bp imperfect repeats that define the 16-repeat L allele. Originally described by Nakamura et al.

(10), L

G is equivalent in expression to the S allele

(11) . The allelic frequency of L

G is 0.09–0.14 in Caucasians and 0.24 in African-Americans, and the three alleles (S, L

A, and L

G ) appear to act codominantly

(11), potentially underlying some discordant published findings.

Childhood adversity may produce a biological and clinical diathesis for mood disorders that endures into adulthood

(14) . Childhood separation from parents, sexual and physical abuse, and adult losses may precede the onset of major depression

(15,

16) . Current stressful life events have a relationship with onset of major depression, modulated at least in part via an interaction with genetic predisposition

(2 –

4,

16 –18) . Life events predict depression and suicidal ideation or a suicide attempt in child, adolescent, and young adult carriers of the S allele of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism

(16,

19,

20) . These studies did not genotype subjects for the triallelic genotype, and no study has identified a biological intermediate phenotype. Therefore, we report here a study of the effect of the triallelic 5-HTTLPR genotype on the relationship of severity of recent stressful life events and reported childhood abuse to severity of a current major depressive episode and suicidality in adults and to CSF 5-HIAA in a subgroup of subjects.

Discussion

The present study replicates and extends findings of a 5-HTTLPR/environment interaction effect on depression—reported in children

(16), female adolescents

(19), and young adults

(20) —in an older study group and employing direct face-to-face severity ratings and triallelic genotyping of the 5-HTTLPR polymorphism. The triallelic approach found 10.5% of the L alleles were the lower expressing L

G allele that otherwise would have been treated as the higher expressing L

A allele. This is the first demonstration that genotype independently predicts severity of major depression directly and via a genotype or S′ allele-by-life events interaction effect on depression severity. This model explained 31% of the variance in severity of major depression, with genotype and the interaction term contributing comparable components. Genetic factors explain 40%–70% of the probability of major depression

(4,

5), but genetic contribution to severity of major depression has been less studied. Major depression severity correlates with severity of recent life events

(3,

4,

17,

18), but when we considered genotype, life events alone no longer had an effect. Instead, the S′ allele had both a direct effect and an indirect effect on severity of depression by modulating the impact of life events.

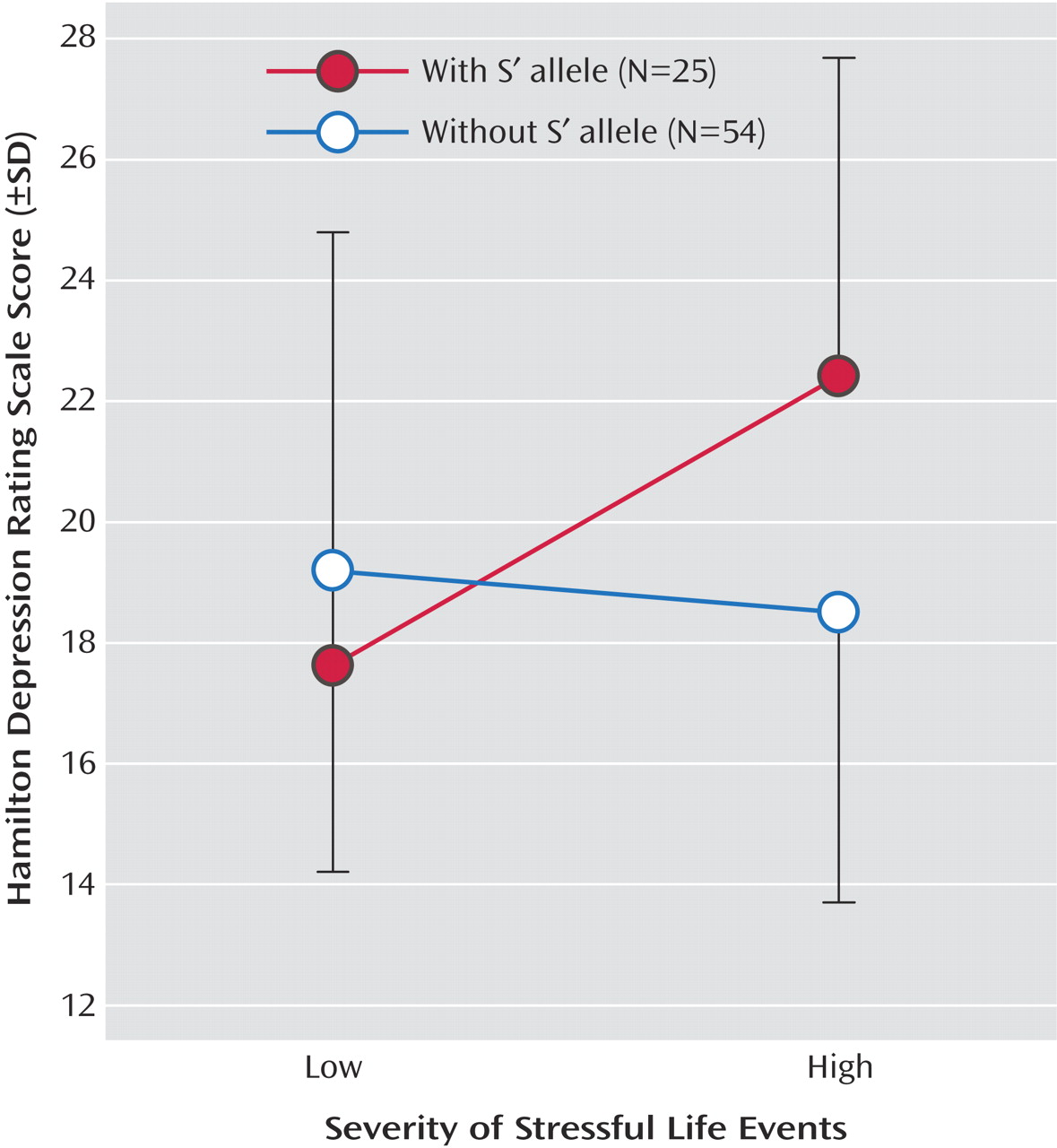

Like others

(16,

19), and consistent with the alleles being codominant in terms of expression levels, we found an effect of genotype on depression severity. The severity of life events and symptoms of anxiety and depression are familial

(29), and one explanation may be that the relationship of life events to severity of depression and the experience of life events are dependent on a common genetic effect, such as the S′ allele. The relationship shown in

Figure 1 is comparable to both other reports on 5-HTTLPR/environment interaction and depression

(19,

20) . The S′ allele appears associated with higher depression scores only when life events were more severe. Kaufman et al.

(16) examined severe levels of maltreatment requiring separation from parents and found that therapy ameliorated the effect of the S allele. This relationship needs further study.

Measurement of depression differed among studies. We used a face-to-face diagnostic interview and clinician-rated severity of depression. Caspi et al.

(19) made a diagnosis and used informant reports of depressive symptoms by mailing a brief self-report questionnaire to persons close to the proband. Eley et al.

(20) gave parents a self-report questionnaire to be completed by the adolescent offspring. Kaufman et al.

(16) read a self-report depression measure to the children, and most of their cases did not meet criteria for major depression. Our study and others also used different methods to assess life events over the prior 6 months. Kaufman et al.

(16) defined a common stressor of sufficient maltreatment as exposure to familial violence requiring removal of the child proband from the parental home within the previous 6 months. Caspi et al.

(19) employed number of events, while we scored severity and impact of stressful life events

(25) . The robustness of the relationship of the 5-HTTLPR genotype-adversity interaction effect on depression is emphasized by the agreement between four studies despite methodological differences.

Of note, to minimize recall effects we assessed stressful life events in the 6 months prior to evaluation, yet the median duration of major depressive episodes was 24 months. Thus, we captured stressful life events during the depressive episode, and some stressful life events may have been a consequence of depression. Nevertheless, a genotype that increases vulnerability to the effects of life events on depression will affect the impact of a stressful life event regardless of whether it was triggered by the depression.

The biologic intermediate phenotype that mediates the 5-HTTLPR effects on depression is uncertain. Lower postmortem 5-HTT binding in the prefrontal cortex in major depression, and lower in vivo 5-HTT binding in the brainstem raphe nuclei appear unrelated to genotype

(30,

31), although we have reported less 5-HTT gene expression in depressed suicide victims

(32) . Paradoxically, serotonin reuptake inhibitors help depression. Transient 5-HTT inhibition in rodents in infancy produces a depressive behavioral phenotype

(33) suggesting a developmental effect is responsible, perhaps involving heightened amygdala sensitivity to negative experiences as reported in those with the S allele

(34) . Nonhuman primates having the S allele experience a persistent decline in serotonin activity after maternal separation as measured by CSF 5-HIAA

(35) . This decline in serotonin function results in greater aggression, impulsiveness, and risk-taking as an adult. If such an effect of childhood adversity on serotonin function with the S allele could be demonstrated in humans, it may explain greater depression following maternal separation

(16) and vulnerability to life events later in life

(19,

20) .

In agreement with Jonsson et al.

(36) we failed to find an association of 5-HTTLPR with CSF 5-HIAA. However, our subgroup may have been too small to detect a weaker effect, since others

(37) have reported lower CSF 5-HIAA in association with the S allele. The identification of a biologic phenotype remains a goal for future study.

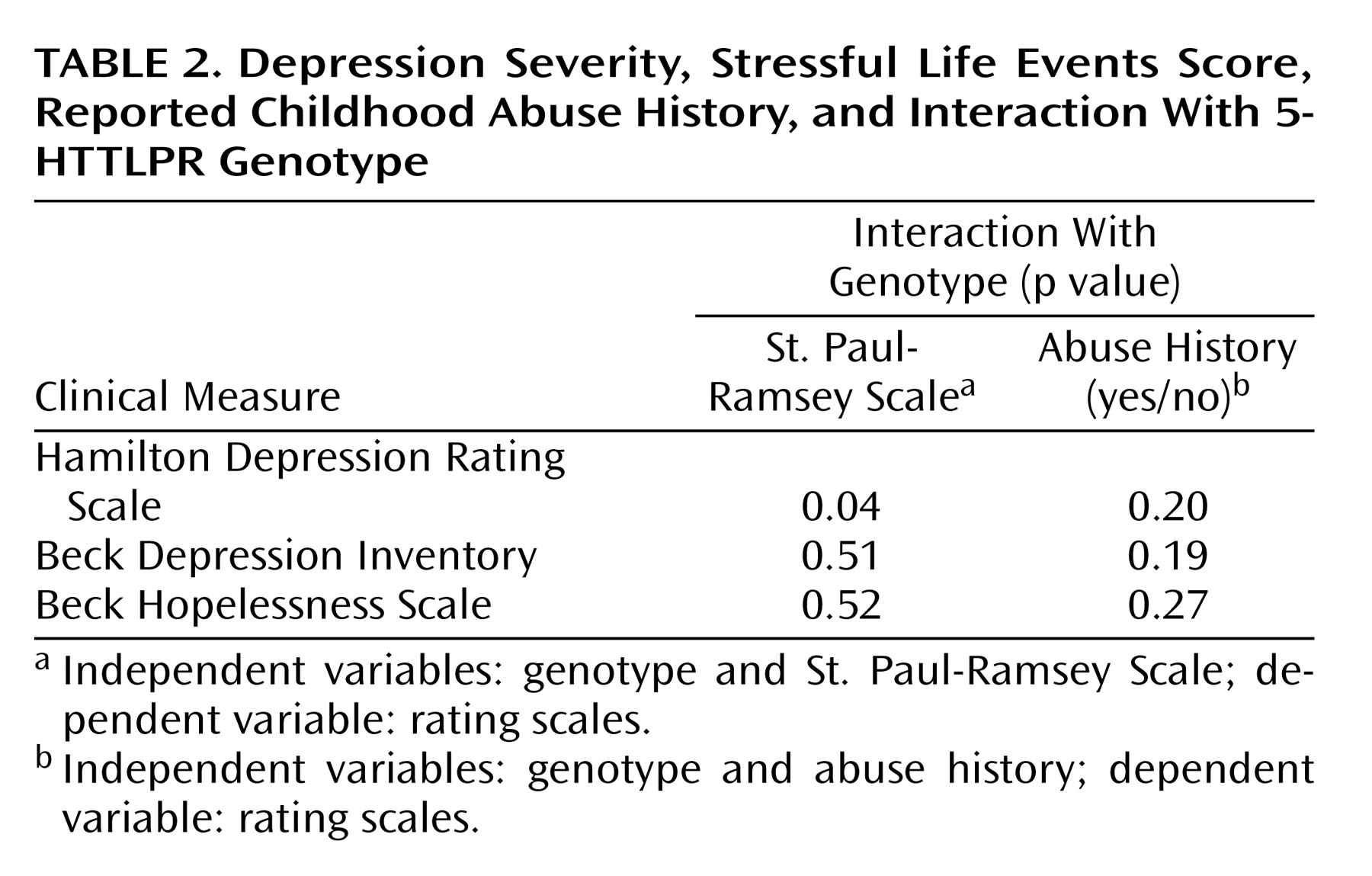

Our exploratory analysis found no association of 5-HTTLPR genotype with reported history of childhood abuse, and the interaction did not predict severity of depression. Others have reported that childhood maltreatment and the S allele predict depression in childhood and young adults

(16,

19) perhaps because they collected data contemporaneously. Study group size prevented an analysis of stressful life events, genotype, and abuse history. Clearly, further study is needed to determine whether the S′ allele favors the appearance of adult major depression in those who report childhood abuse and whether this is related to an effect on serotonin function.

Eley et al.

(20) examined both sexes but found a significant interaction for female subjects only. Our findings remained significant in female subjects only, but we had too few male subjects to analyze them separately. Since two previous studies have not analyzed male subjects separately, it remains to be determined whether the effect is comparable in both sexes. Stress hormone responses in nonhuman primates who were peer-reared are elevated in female but not male subjects with the S allele

(38) suggesting that the gene/environment interaction might be stronger in women.

Stressful life events occurring after age 21 predict suicidal ideation or attempt at age 26 in S allele carriers

(19) . Two meta-analyses of the association of suicidal behavior with 5-HTTLPR polymorphism disagree: one found a weak association with suicidal behavior

(12) and the second did not

(39) . We did not find an association with suicide attempts or ideation despite direct interviews quantifying severity of ideation and obtaining a lifetime suicide attempt history. Only one of three other studies

(19) report on suicidal ideation and attempts. However, this study did not control for depression severity and examined attempts reported by 3% of the sample in the context of depressive episode and not lifetime. We previously reported lower postmortem ventral prefrontal cortical 5-HTT binding in suicide victims but did not find an association with 5-HTTLPR genotype

(30) . We found no association with suicide

(30) or suicide attempts, raising questions regarding the results of one previous report

(19) . Our finding that suicides occurred only in first-degree relatives of probands with the S′ allele, while not statistically significant in our study group, is consistent with previous reports

(12,

40) .

This study replicates and extends findings in children, female adolescents, and young adults of the stress sensitivity of depression associated with the S′ allele

(16,

19,

20) . We also found an independent effect of genotype on depression severity in adults. Larger prospective studies with more contemporaneous data on childhood abuse and assessment of recent life events prior to the onset of major depression will help clarify these gene/environment relationships in mood disorders. The biological mechanism whereby the S′ allele conveys these effects is unknown, but amygdala sensitivity to stressful events and childhood stress-induced serotonin dysfunction are candidate mechanisms.