The clinical heterogeneity of schizophrenia is a major obstacle to understanding the pathophysiology of this disorder. In recent years, factor analytic studies of schizophrenic symptoms have greatly influenced studies of this heterogeneity

(1–

4). Despite some differences, the findings of the factor analytic studies have been fairly consistent in identifying at least three syndromes or dimensions within schizophrenia: hallucinations and delusions, disorganization of thought and behavior, and negative symptoms. These three clinical syndromes constitute one way to define subgroups that may be more homogeneous relative to course and pathophysiology.

Recent research has focused on the relationship of phenotypic markers and putative subgroups within schizophrenia. A number of studies have shown that patients with schizophrenia have an increased number of abnormal signs on neurological examination

(5). Some studies have related neurological signs to negative symptoms

(6–

9), nonparanoid subtype

(10), social withdrawal

(11), blunted affect

(10), and positive and negative symptoms

(12,

13). However, relationships between neurological signs and different clinical symptoms are not a consistent finding

(14–

18). Differences in ways of assessing both neurological signs and clinical symptoms may account for some of the discrepancies mentioned above.

We previously found that patients meeting criteria for the deficit syndrome, which defines a symptom subtype with enduring, idiopathic negative symptoms, had an increased severity of neurological signs, especially signs related to abnormal sensory integration

(19). However, few studies have examined the relationship of neurological signs to all three clinical syndromes of schizophrenia

(20–

22). In the study reported here, we examined the relationship between neurological signs and these syndromes.

RESULTS

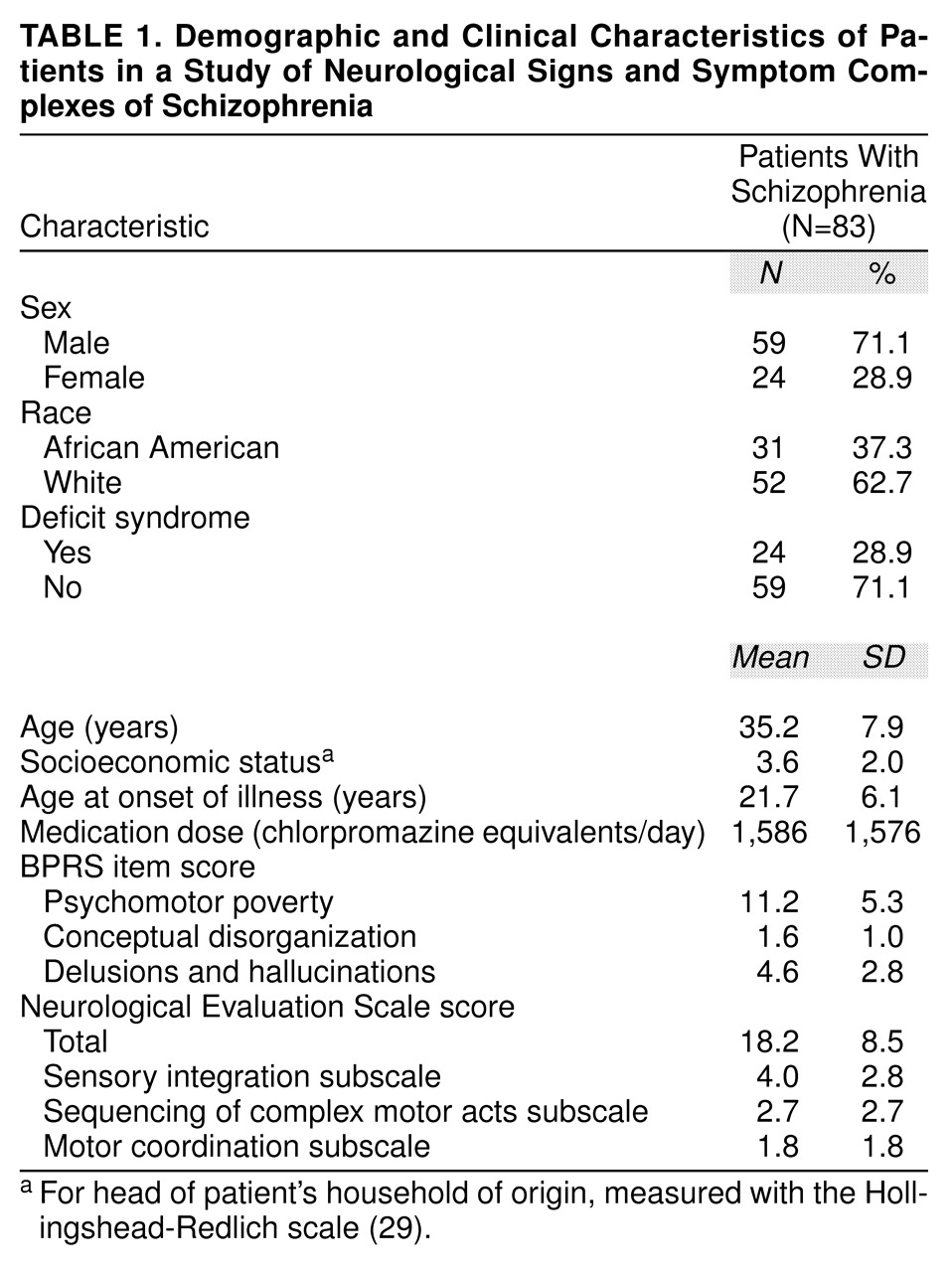

The clinical and sociodemographic features of the patients are shown in

table 1. At the time of testing four patients were taking clozapine, 78 patients were taking conventional antipsychotics, and one patient was drug free. Fifty-five patients were receiving anticholinergics.

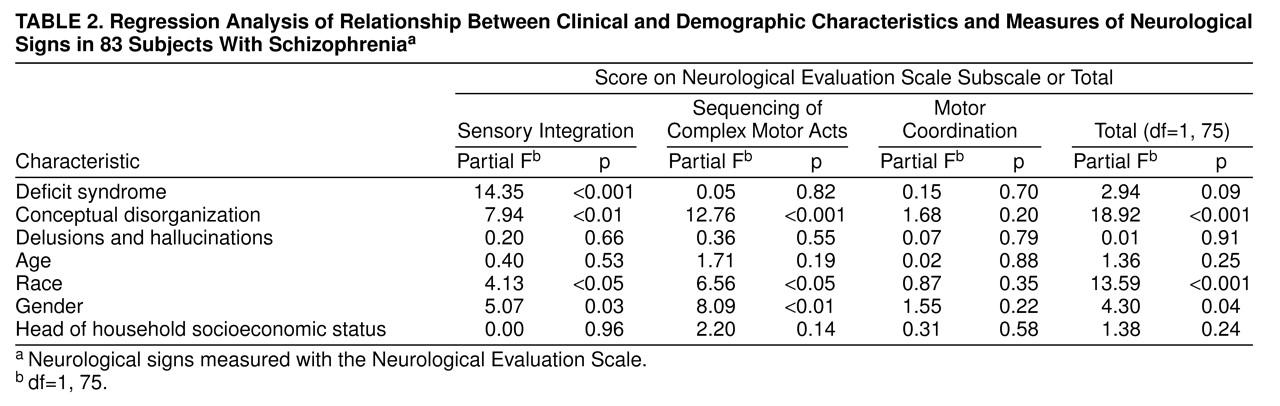

In the multiple regression analyses that included all 83 patients: 1) the Neurological Evaluation Scale total score was significantly related to disorganization, 2) the Neurological Evaluation Scale sensory integration score was significantly related to both deficit status and disorganization, and 3) the Neurological Evaluation Scale score for sequencing of complex motor acts was significantly related to disorganization (

table 2). Both race and gender were related to Neurological Evaluation Scale scores for sensory integration and sequencing of complex motor acts and to the total scale score. All correlations with gender and race were in the same direction, with female and black subjects scoring higher. In the multiple regression analyses using data from the 79 patients who were drug free or receiving a typical neuroleptic, with drug dose as an additional independent variable, the same pattern of relationships was found (data not shown). Anticholinergic status was not related to any of the Neurological Evaluation Scale scores (data not shown).

When the sum of scores for the BPRS negative symptoms items was used instead of the deficit/nondeficit categorization as the measure of psychomotor poverty, the BPRS negative symptoms construct was not related to any of the Neurological Evaluation Scale subscales or to the total score on that scale. Specifically, in contrast to the deficit categorization, the BPRS negative symptoms construct was not related to sensory integration (F=3.4, df=1, 72, p=0.07). The other relationships between demographic and clinical features and neurological impairment essentially remained the same (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In examining the relationship between neurological signs and clinical syndromes, our major findings were that 1) disorganization was significantly related to the total score and scores for sensory integration and the sequencing of complex motor acts on the Neurological Evaluation Scale, 2) the deficit syndrome was significantly related to the sensory integration score, and 3) hallucinations/delusions and a measure of negative symptoms derived from the BPRS were not related to the total score or to scores on any of the subscales of the Neurological Evaluation Scale. No changes in the patterns of clinical and neurological variables were found when neuroleptic dose was used as an independent variable, and anticholinergic use was not related to subscale scores or total score on the Neurological Evaluation Scale.

The study reported here had some limitations. Only a single item was used to assess conceptual disorganization, although this item appeared to have sufficient sensitivity to detect multiple relationships. Our results are most likely to generalize to patients with chronic illness who are clinically stable and have moderate to severe residual symptoms. In addition, because we did not have scores on the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms or the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms for the study sample, no direct comparison to previous studies that used these scales can be made. Another possible limitation is that we did not have scales to measure tardive dyskinesia or extrapyramidal symptoms that could contribute to the presence of neurological signs. However, neither drug dose at the time of assessment nor use of an anticholinergic was related to any of the Neurological Evaluation Scale subscale scores, and previous studies have suggested little if any effect of medications on neurological signs as measured by such scales as the Neurological Evaluation Scale

(6,

13).

Our findings are similar to those of some previous studies. Liddle

(20) reported that disorganization and a negative symptom measure (the latter including blunting of affect, poverty of speech, and lack of spontaneous movement), but not hallucinations and delusions, were related to stereognosis, graphesthesia, and right-left confusion. These signs are included in the Neurological Evaluation Scale sensory integration subscale, and the results of Liddle therefore largely seem to provide support for the generalizability of our results. In our previous study, with a much smaller number of patients and a different design, patients with deficit syndrome scored significantly higher than nondeficit patients on the Neurological Evaluation Scale sensory integration subscale

(19). The other two clinical syndromes were not considered in the same way as in the present study. In that earlier study, the deficit group’s greater impairment with regard to neurological signs was also restricted to sensory integration. Some of the patients included in the previous study (N=34) were also included in the study reported here, therefore the current finding cannot be considered an independent replication of our previous finding.

When the deficit/nondeficit categorization was replaced by a measurement of negative symptoms based on the BPRS, the relationship was no longer significant. This difference could be due to the extra variability that is added when scales such as BPRS and Schedule for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms are used and secondary negative symptoms are included in the negative dimension. The deficit categorization includes only patients whose negative symptoms are judged to be idiopathic or due to the disease itself, as is the case in this study, and therefore this categorization can be used instead of a broader negative dimension to further reduce the heterogeneity in the conceptualization of schizophrenia. On the other hand, although significance was lost when the broader negative measure was used, the correlation with sensory integration approached significance (partial F=3.47, df=1, 65, p=0.07 for the BPRS negative dimension and partial F=15.05, df=1, 76, p<0.001 for the deficit categorization). The slightly lower reliability for the continuous measure than for the deficit/nondeficit categorization may have caused the difference in the study reported here, although other studies have also found the deficit/nondeficit categorization to be more sensitive to group differences than are negative symptoms more broadly defined

(30–

33).

Items that assess sensory integration are thought to reflect in part parietal lobe function. Consistent with neuropsychological

(34) and functional imaging data

(30), our results point toward parietal dysfunction in patients with the deficit syndrome. Other studies have shown other neurobiological and treatment response differences between deficit and nondeficit groups

(2,

19,

27,

30–

48).

In this study, conceptual disorganization was related to the sequencing of complex motor acts and to the Neurological Evaluation Scale total score, suggesting both a possible specific frontal dysfunction and a more global impairment. Schroder et al.

(21) reported that the disorganized patients in their study had the highest neurological sign scores. The same group of researchers

(22) also found that disorganization but not the other two syndromes were related to neurological signs. The scale used in both of these studies consisted of 17 neurological signs, most of which are included in the Neurological Evaluation Scale (e.g., tandem walk, fist-edge-palm test, graphesthesia, mirror movements). Compared to the other two syndromes, disorganization in schizophrenia has been related to working memory dysfunctions mediated by the prefrontal cortex

(49,

50), as well as to impairment in neuropsychological tests assessing frontal function (e.g., Wisconsin Card Sorting Test) and lack of improvement in frontal test performance after coaching and incentives

(51).

The lack of association that we found between hallucinations and delusions and neurological signs is in agreement with previous studies

(20,

22). However, the lack of a nonpsychotic comparison group limits our ability to interpret the meaning of this negative finding, other than to say that this component of this illness appears to be less strongly related to neurological impairment than are disorganization and the deficit syndrome.

Neurological Evaluation Scale motor coordination was not associated with any of the three clinical syndromes. However, this subscale also had the lowest interrater reliability (ICC=0.72) of the subscales, and is the least stable over time

(35); the lower stability and reliability of these items may have contributed to the lack of an association with one of the clinical syndromes. The Neurological Evaluation Scale motor coordination score has been found to correlate with extrapyramidal symptoms

(35), although we found no relationship to drug dose or anticholinergic use. Previous studies have also failed to find a relationship between neurological signs and either antipsychotic dose at the time of assessment or lifetime exposure to neuroleptics

(5).

In theory, the distinct relationships between the clinical syndromes and the Neurological Evaluation Scale subscales scores and total score may reflect different reliabilities for the clinical dimensions assessed

(52). However, this explanation does not seem to apply in the study reported here, as the reliabilities for the three clinical assessments were similar (ICCs ranging from 0.73 for the Schedule for the Deficit Syndrome to 0.88 for items 12 and 15 of the BPRS).

Gender was associated with two of the Neurological Evaluation Scale subscores and the total score; female patients scored higher than male patients. Previous studies in which neurological signs were assessed as a total score have not found a relationship between sex and neurological impairment

(6,

8,

16). However, Malla et al.

(53) also found a more robust relationship between neurological signs and Neurological Evaluation Scale factors in female subjects than in male subjects. The relationship between race and neurological impairment has also been previously reported

(6,

54). In the study reported here, differences by race reached significance for total, sequencing, and sensory integration scores. Although this result suggests that neurological performance differs among racial groups, confounding by some other variable, such as socioeconomic status in early life, cannot be ruled out.

Results from the study reported here further support the biological validity of a three-syndrome construct within schizophrenia. Differential relationships among particular aspects of neurological impairment in schizophrenia and the three clinical syndromes raise the possibility of differences in the pathophysiological processes that are the basis of each syndrome. However, the three-syndrome model may apply not only to schizophrenia, but to other psychotic disorders as well

(55,

56). It would be interesting to determine whether the relationship of these clinical syndromes and biological markers such as neurological signs extends beyond schizophrenia.