Controversy exists regarding the long-term course of cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. While a study of institutionalized elderly patients found a high rate of non-Alzheimer’s dementia

(1) and an apparently accelerated rate of cognitive decline

(2), several longitudinal and cross-sectional studies of younger patients with schizophrenia failed to find cognitive deterioration

(3–

5). Conclusions from previous investigations were often limited, however, by variable diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia, inadequate cognitive assessment, and absence of comparison groups. Few studies have examined the course of cognitive impairment in aging outpatients with schizophrenia. The number of older patients with schizophrenia is expected to increase dramatically in the coming decades

(6), and most such patients live in the community rather than in institutions

(7).

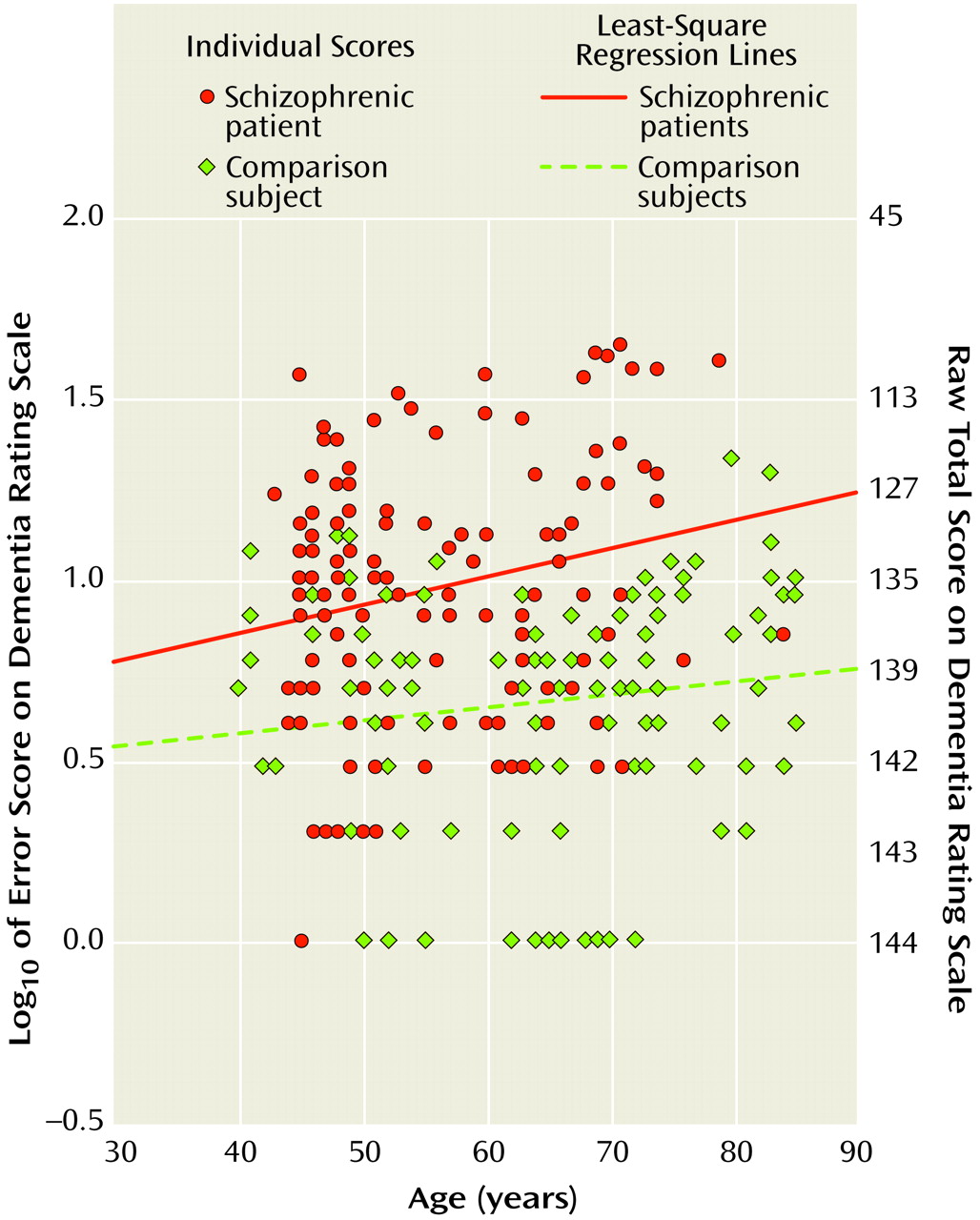

The present cross-sectional investigation of middle-aged and elderly patients used DSM-III-R or DSM-IV criteria for diagnosis, included a group of normal comparison subjects, and employed a standardized instrument for assessing global cognitive performance, the Mattis Dementia Rating Scale

(8). We hypothesized that Dementia Rating Scale scores would worsen with advancing age in both the schizophrenia and normal comparison groups, and the slope depicting age-related variation in the Dementia Rating Scale score would be steeper for the subjects with schizophrenia.

Method

Subjects with schizophrenia (N=116) were recruited from local medical centers, county mental health facilities, and private physicians. Those who were 40–85 years of age, living in the community, and whose onset of illness occurred before age 45 were chosen to participate. Diagnoses were determined by using the patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R or DSM-IV

(9,

10). The schizophrenic outpatients were a mean age of 56.6 years (SD=9.9), had a mean of 12.6 years (SD=2.4) of education, and a mean illness duration of 30.9 years (SD=11.3); 78% (N=90) were male, and 77% (N=89) were Caucasian. Although all were outpatients at the time of study, 27% (N=31) had previously been hospitalized for more than 3 years, 59% (N=69) for 2 months to 3 years, and 14% (N=16) for less than 2 months. On average, the patients had two axis III comorbid medical conditions (SD=1.7). Exclusion criteria were 1) too physically or psychiatrically unstable to undergo assessments, 2) no corroborating source for subject history, 3) history of serious violence toward others, 4) history of head injury with loss of consciousness for more than 30 minutes, 5) current seizure disorder, or 6) substance dependence. Findings from a subset of these patients have been reported previously

(11).

Normal comparison subjects (N=122), free of any major neuropsychiatric disorders, were recruited from the local community. These subjects were a mean age of 64.6 years (SD=13.0), and had a mean of 13.3 years (SD=2.6) of education; 37% (N=45) were male, and 67% (N=82) were Caucasian. They had on average 2.2 axis III comorbid medical conditions (SD=1.9).

Each subject provided written informed consent to participate in the research program.

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

(12) was used to rate severity of psychopathologic symptoms. The Mattis Dementia Rating Scale

(8) was chosen to assess global cognitive function, since it is reasonably comprehensive, standardized, easy to administer (taking about 40 minutes), and is less prone to restricted range effects (i.e., floor and ceiling effects) than briefer measures.

For demographic and clinical comparisons of groups, Student’s t tests were employed. The slope of the regression of Dementia Rating Scale impairment on age was calculated separately for the schizophrenia patients and normal comparison subjects, and the equivalence of these regression weights was tested

(13). To meet parametric assumptions, Dementia Rating Scale scores were transformed by using the following equation: Dementia Rating Scale impairment=log

10 (145–Dementia Rating Scale score). All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

Normal comparison subjects were older than the schizophrenic subjects (t=5.3, df=236, p<0.001), although the age range of the two groups was identical. The schizophrenic group had more men (χ2=41.9, df=1, p<0.001) and was less educated (t=2.03, df=236, p=0.02) than the normal comparison group. The two groups were similar in the number of comorbid medical conditions and proportion of Caucasians. It was no surprise that the schizophrenic subjects had higher BPRS scores (mean=33.2, SD=8.0) than the normal comparison subjects (mean=22.5, SD=3.5) (t=13.9, df=229, p<0.0001). The schizophrenia group also had lower Dementia Rating Scale scores (mean=132.3, SD=10.1) than did the normal comparison subjects (mean=139.3, SD=3.6) (t=7.28, df=236, p<0.0001).

Figure 1 shows the slopes depicting age-related variation in the Dementia Rating Scale impairment score for the schizophrenic and normal comparison subjects. The slope for the schizophrenic group was 0.007 (r=0.21, df=114, p=0.03), and the slope for the normal comparison group was 0.004 (r=0.16, df=120, p=0.08). There was no significant difference between these slopes (F=0.81, df=1, 234, p=0.37). Because of age and gender differences between the groups, analyses were also conducted on age- and gender-matched subsamples; the results were similar.

Discussion

While global cognitive impairment was worse in the subjects with schizophrenia than in normal comparison subjects, there was no evidence of steeper age-related cognitive decline in those with schizophrenia. This is remarkable considering that the subjects in the schizophrenia group had been ill for many years, with all the well-known antecedents, accompaniments, and consequences of a severe psychiatric disorder. Our results support the notion of stable encephalopathy in schizophrenia

(3–

5).

Regarding study group characteristics, we did not include adults aged 18–39 because of considerable differences between young adult and elderly patients in variables such as age at onset and duration of illness, daily neuroleptic dose, and prevalence of substance abuse. Patients with late-onset schizophrenia were excluded because of known differences in cognitive performance that might confound the findings

(14). The primary limitation of the current investigation was its cross-sectional design, with its inherent cohort effects such as survival and preferential recruitment of less ill patients.

The present results differ from those that were based on chronically institutionalized patients, which found a high rate of dementia in elderly patients with schizophrenia

(1,

2). Since the present study group was somewhat younger than those of the earlier studies, a possibility of abnormally rapid cognitive decline in very old patients cannot be excluded. Additionally, our community-dwelling patients might be expected to show a milder course of illness than the institutionalized ones. As stressed by Cohen

(7), however, community-dwelling individuals are far more representative of the population of older schizophrenia patients. The current findings also contrast with our previous study, which reported that span of apprehension performance and pupillary responses showed a steeper age-related slope in schizophrenia patients than in normal comparison subjects

(15). This discrepancy may be due to a smaller sample size (33 patients) in the previous investigation, or there may be differential rates of decline on certain specific versus global cognitive measures.

In summary, the present cross-sectional study suggests that community-dwelling older patients with schizophrenia do not seem to have a rapid rate of global cognitive decline. Long-term prospective investigations are needed to confirm and elaborate on these findings.