Social phobia (also known as social anxiety disorder) is a prevalent, often functionally impairing condition

(1). The more pervasive form of the illness, generalized social phobia, is associated with the greatest disability

(2), with impairment escalating as the number of feared social situations increases

(3). Generalized social phobia has recently been shown to be responsive to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), marking an important advance in the treatment of this condition

(4–

7). These studies show, however, that response rates to SSRIs in generalized social phobia peak at 50%–60%; even fewer patients (20%–30%) experience improvement that could be characterized as remission. Consequently, a role exists for adjunctive treatments that might further improve outcomes. An open-label trial of buspirone augmentation of SSRIs in social phobia suggested that it might be effective for this purpose

(8), although to our knowledge no controlled trial has yet been conducted to confirm this finding.

Our rationale for testing pindolol as an adjunct to SSRIs for social phobia was twofold. First, there is a long tradition of using β blockers to treat anxiety related to public speaking and other types of performance anxiety, both of which are encompassed by the social phobia diagnosis

(9). It is less clear, however, that β blockers are effective for other forms of social phobia, particularly for generalized social phobia. In a landmark study comparing the monoamine oxidase inhibitor phenelzine to the β blocker atenolol, the latter proved ineffective as a monotherapy for patients with generalized social phobia

(10). Atenolol also lacked efficacy in another study of social phobia, where it was no more effective than placebo

(11). Still, these observations would not preclude the possibility that a β blocker might be effective as an adjunct to other therapies, such as an SSRI.

The second reason for studying pindolol was that in addition to being a β blocker, it has 5-HT

1A autoreceptor antagonist properties

(12) that have garnered it prominence as a possible adjunct to antidepressants in the treatment of major depression

(13,

14). Although its usefulness to enhance the efficacy of SSRIs for depression is in doubt, pindolol has been shown to accelerate the response to SSRIs in some

(15,

16), but not all studies

(17,

18).

For these reasons, we hypothesized that pindolol would augment the effects of SSRI treatment in generalized social phobia. This double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study was designed to test this hypothesis. To our knowledge, this report describes the first double-blind, placebo-controlled study of an adjunctive pharmacologic treatment for social phobia.

Method

This study was approved by the Committee on the Use of Human Subjects of the University of California, San Diego, School of Medicine. All subjects provided informed written consent. Subjects were patients with a clinically predominant diagnosis of DSM-IV generalized social phobia (comorbid mood disorders were not exclusionary) who had less than an excellent (i.e., Clinical Global Impression [CGI] of change “very much improved”) response to 10 weeks of treatment with a maximum tolerated dose of the SSRI paroxetine. Of 31 patients for whom paroxetine treatment was started, six dropped out during open-label paroxetine treatment because of adverse events or unspecified reasons, two were considered responders to paroxetine and did not proceed further in the study, four were eligible but elected not to participate in the double-blind phase, and five dropped out after completing only one arm or less of the double-blind phase.

Subjects were randomly assigned to receive either 5 mg of pindolol t.i.d. or placebo for 4 weeks. The 4 weeks was followed by a 2-week taper period, then crossover to the other agent (i.e., either pindolol or placebo), 4 weeks of treatment with the other agent, followed by another 2-week taper period. The administration of pindolol or placebo was conducted under double-blind conditions. Eight subjects received pindolol during the first treatment period, and six received it during the second treatment period. Subjects continued to take their maximally tolerated, stable dose of paroxetine throughout the study. No other concurrent psychotropic medications or specific psychotherapies were permitted. Fourteen patients met entry criteria and completed both phases of the double-blind crossover.

Changes in scores on the clinician-rated Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale

(19) and self-rated Social Phobia Inventory

(20) were compared across the two crossover periods, as was the number of responders in each period. Responders were identified by a CGI rating of change

(21) as “very much improved” relative to the start of treatment. Change scores during each period on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Inventory were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) with treatment period as the repeated measure

(22). Two-tailed tests were used; p values of <0.05 were deemed statistically significant.

Results

Before treatment with paroxetine, the mean Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Inventory scores of the 14 subjects who later went on to complete the double-blind crossover study were 79.7 (SD=23.9) and 36.6 (SD=9.6), respectively. After a minimum of 10 weeks (range=10–14 weeks; mode=10 weeks) of treatment with open-label paroxetine as described, the mean Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale and Social Phobia Inventory scores of the participants had been reduced to 53.8 (SD=16.9) and 26.6 (SD=9.2), respectively. The mean paroxetine dose before randomization was 46.4 mg/day (SD=8.4). At this point the subjects entered the double-blind crossover study.

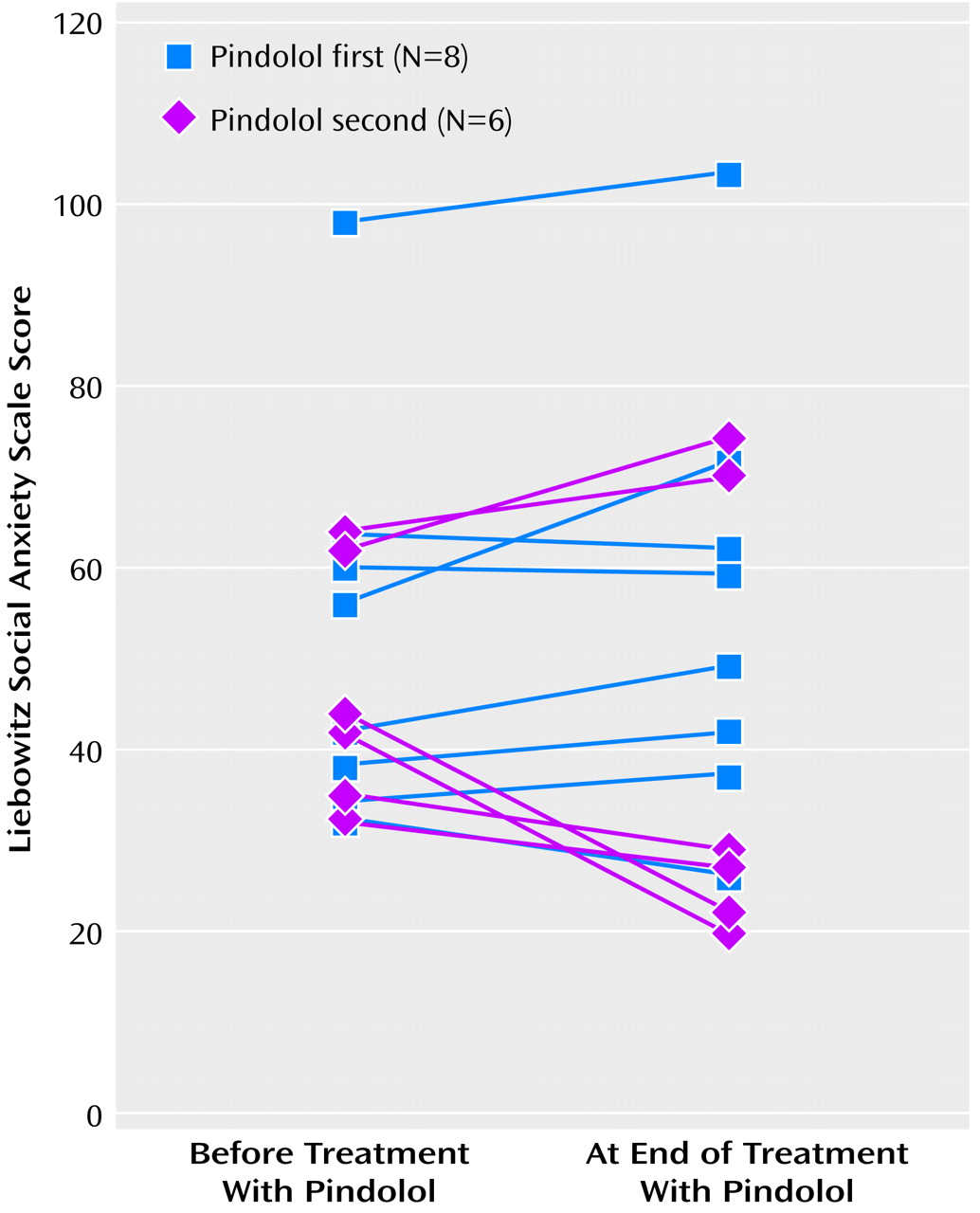

No carryover effect was detected on either the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale or the Social Phobia Inventory (F=0.96, df=1, 11, p>0.35, and F=0.88, df=1, 11, p>0.37, respectively). We therefore went on to test for period and treatment effects. No period (Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale: F=1.52, df=1, 11, p>0.24; Social Phobia Inventory: F=0.03, df=1, 11, p>0.86) or treatment (F=1.75, df=1, 11, p>0.21, and F=0.62, df=1, 11, p>0.45, respectively) effects were detected on either the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (

Figure 1) or the Social Phobia Inventory. The power of this study to detect a drop of 10 points on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale was 70%; the power to detect a 15-point drop was 96%. Only one subject was considered a responder in either arm of the crossover. This subject became a responder while taking placebo; she subsequently became a nonresponder when crossed over to the pindolol arm.

Conclusions

Despite a dual rationale for hypothesizing that pindolol might be effective as an adjunct to SSRIs in the treatment of generalized social phobia, we found no evidence of its utility in this regard. There were no significant differences in social anxiety scores between the placebo and pindolol arms of this double-blind crossover study. Moreover, not a single subject converted to responder status while taking pindolol.

Recent in vivo neuroimaging work with a 5-HT

1A radioligand suggests that the 2.5 mg t.i.d. dose of pindolol used in most depression studies may be too low to consistently augment the effects of SSRIs

(23), and this explanation could possibly account for the negative results of this study. It is unclear whether our somewhat higher dose (5 mg t.i.d.) would be expected to be substantially more effective in this regard. Regardless, given the confluence of clinical data that pindolol probably does not enhance the response to SSRIs in depression—although it may accelerate response

(15,

16)—its lack of efficacy in this study should not be altogether surprising. Irrespective of the explanation, the findings do underscore the lack of utility of β blockers for the treatment of generalized social phobia, either as monotherapy (as seen in other studies) or as an adjunct to SSRIs (as seen here)

(10).

Treatments that can potentiate the effects of SSRIs for generalized social phobia are clearly needed. Pindolol does not appear to be useful for this purpose. Other treatments, both pharmacological and psychological, should be systematically tested under controlled conditions.