The relationship between a history of maltreatment during childhood and adult psychopathology has been well recognized in clinical populations

(1,

2). Although fewer in number than clinical studies, several population-based community surveys have been carried out to examine the relationship between retrospective reports of child abuse and lifetime psychiatric morbidity in the community. The focus of these surveys has been primarily to assess the association between sexual abuse in childhood and adult emotional disorders, predominantly in women

(3,

4). Previous studies

(4–

7), which include a meta-analysis comprising both clinical and community studies

(4), indicate a relationship in women between exposure to sexual abuse during childhood and a wide range of psychiatric disorders, including depression, substance abuse, anxiety disorders, and suicidal behavior. A second meta-analysis that included both men and women concluded that there was a relationship between exposure to sexual abuse during childhood and both depression and general impairment in psychological adjustment

(3). Fergusson et al.

(8) assessed the relationship between a history of childhood sexual abuse and psychiatric morbidity in both male and female subjects, but the study consisted exclusively of 18-year-olds. One of the few surveys to include a representative sample of adult men was a supplement to the Los Angeles Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) study

(9,

10); sexual abuse during childhood was found to be a nonspecific correlate that increased vulnerability for a variety of emotional disorders, including major depressive episodes, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders

(9,

10).

Much less attention has been given to measuring the association between physical abuse and psychiatric morbidity. Duncan and colleagues

(11) examined the relationship between a childhood history of serious physical assault and emotional impairment in a national sample of women. They found that those who reported such victimization experienced higher rates of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance abuse. Similarly, Mullen and colleagues

(12) found an association between childhood exposure to physical abuse and psychopathology in their community sample of women. One study considered childhood exposure to physical abuse in a group of subjects from upstate New York

(13), but the focus was adolescents and young adults. One of the few surveys to explore the relationship between a childhood history of physical and sexual abuse in a representative sample of both men and women was the National Comorbidity Survey

(14). Kessler and colleagues found that being “physically attacked” (the only act of physical abuse considered) was associated with a broad range of psychiatric disorders, including mood, anxiety, and addictive disorders.

This article presents findings from the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey about the relationship between a history of childhood physical and sexual abuse and five major psychiatric disorder categories. A previous article showed that a childhood history of physical or sexual abuse was common among Ontario residents

(15). This report assesses the strength of reported childhood maltreatment as a correlate of psychiatric morbidity among those 15 years of age and older while controlling for age, sex, parental education, and current family income. The diagnostic categories considered in this article were those that had a sample size sufficient for examining their relationship with presence or absence of physical and sexual abuse.

Results

Of the 14,758 households eligible for the Ontario Health Survey, 13,002 (88.1%) participated. Of those, 9,953 (76.5%) took part in the Mental Health Supplement for an overall response rate of 67.4%. Nonparticipation was primarily due to inability to contact the occupant, followed by unwillingness to participate. A detailed description of the sample is provided elsewhere

(16). Of the 8,116 individuals 15 to 64 years of age, data were analyzed for 7,016 respondents after excluding those with missing information on the relevant variables. Briefly, of these remaining respondents, 47.6% (N=3,338) were male, 62.7% (N=4,399) reported being married or in a common law union, 61.7% (N=4,329) described their main activity as working, and 13.6% (N=954) indicated that their family income was below the poverty line.

The age of the male (mean=36.1 years, 95% confidence interval [CI]=35.2–36.9) and female (mean=36.0 years, 95% CI=35.3–36.6) survey respondents was similar.

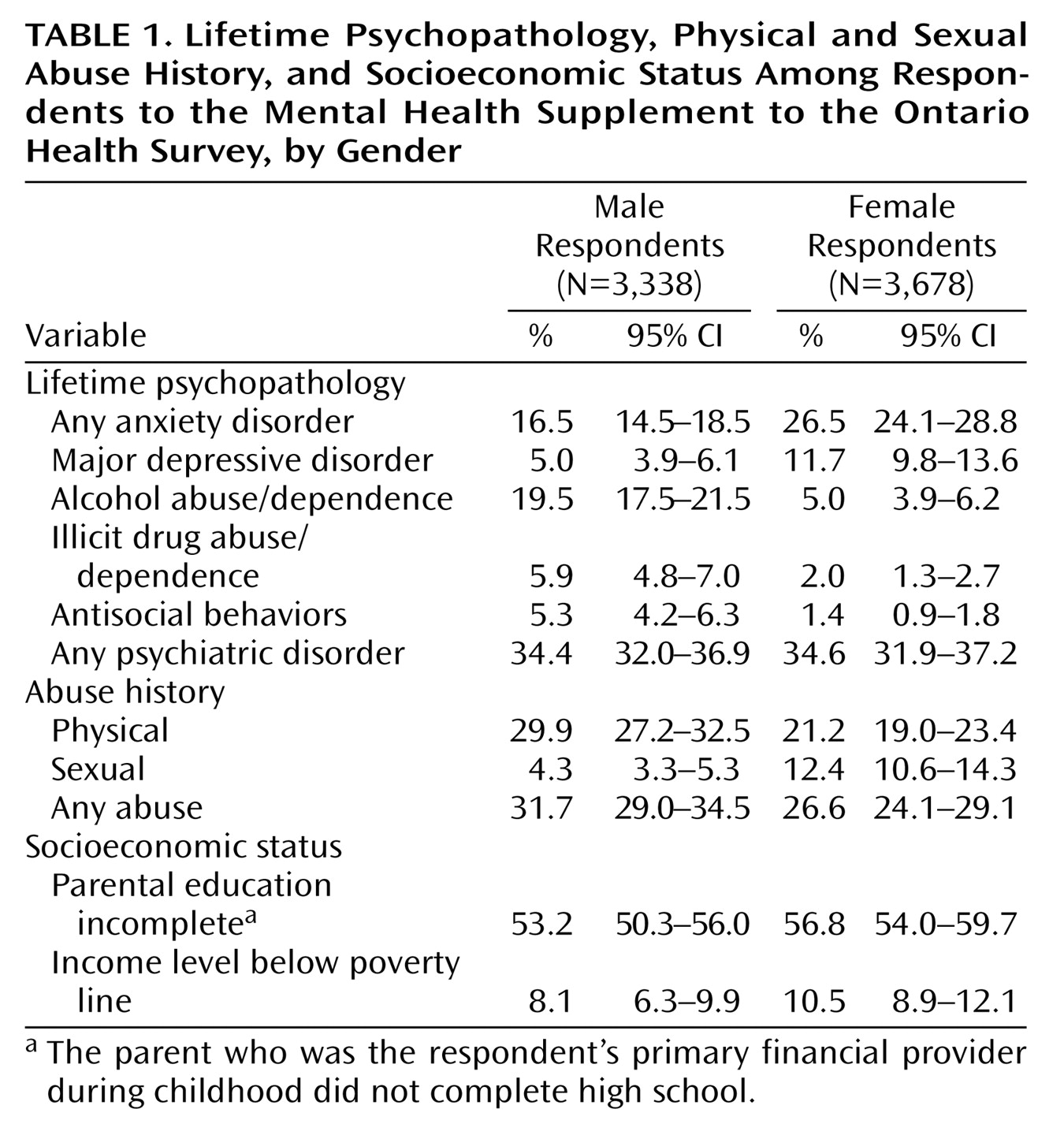

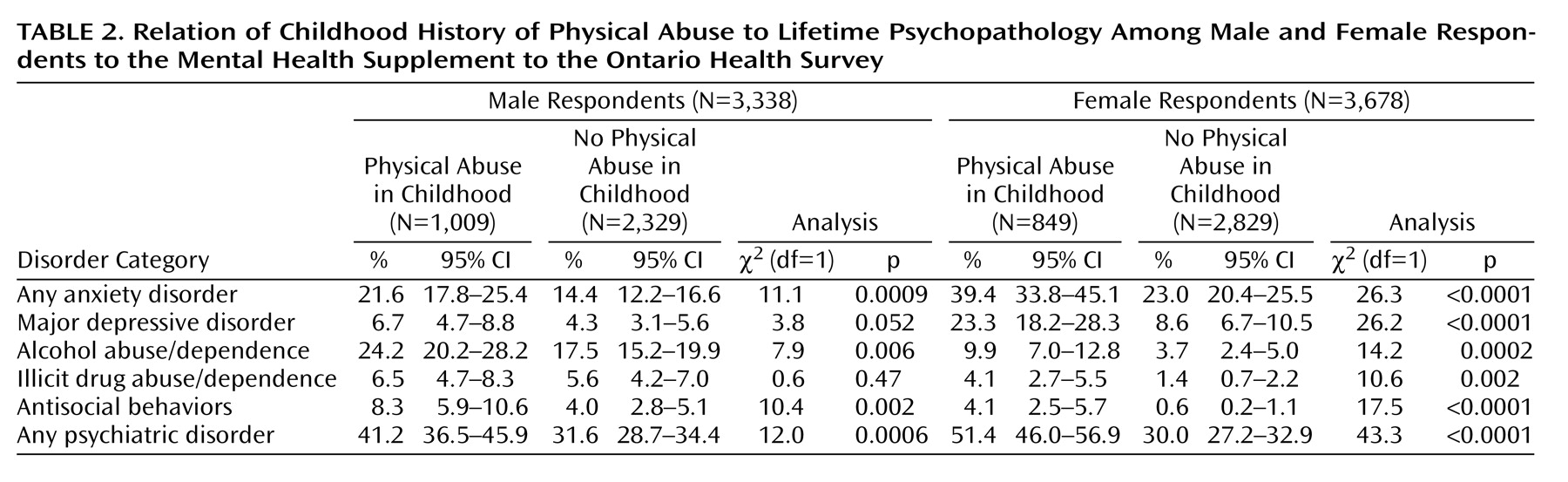

Table 1 outlines the prevalence by gender of lifetime psychopathology, history of childhood physical and sexual abuse, and socioeconomic status. The lifetime prevalence of the five psychiatric disorder categories for male and female survey respondents with and without a history of physical abuse are summarized in

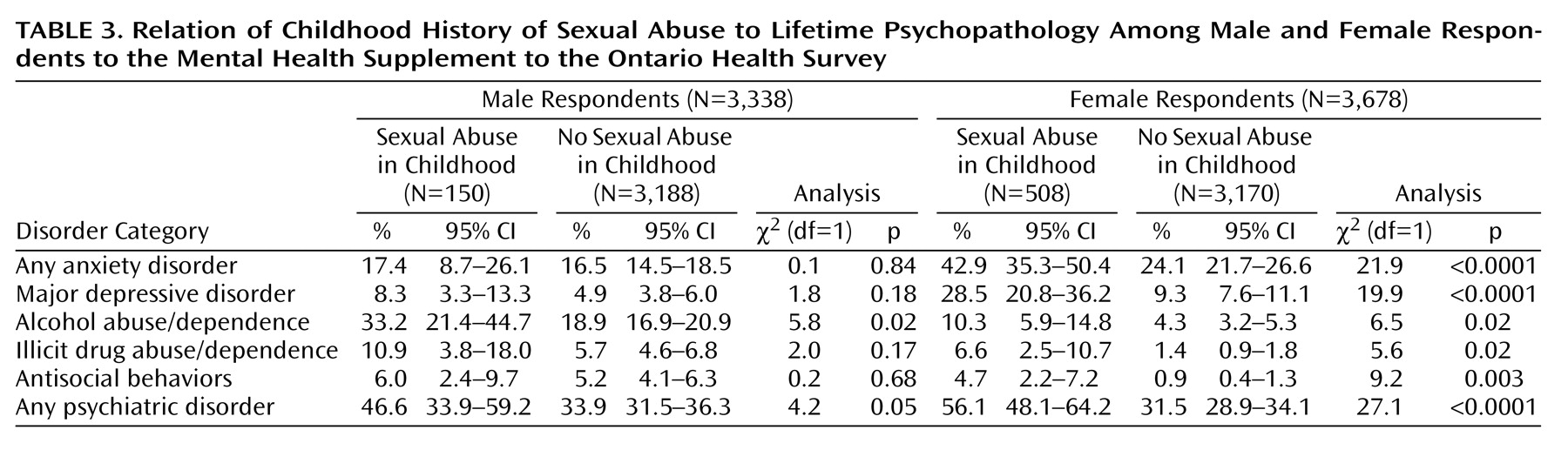

Table 2; findings for sexual abuse are provided in

Table 3.

For both male and female respondents, the likelihood of lifetime prevalence of the specified major psychiatric disorders was increased by a history of childhood physical or sexual abuse. Among female subjects, the association with childhood physical and sexual abuse was statistically significant for all disorders, including the sixth category of “any psychiatric disorder.” Two disorders did not show a statistically significant effect among male respondents with a childhood history of physical abuse compared to those without such a history: major depressive disorder and illicit drug abuse/dependence, although the former approached statistical significance. While men who reported childhood exposure to sexual abuse had higher rates of psychiatric disorder, only the association with alcohol abuse/dependence reached statistical significance.

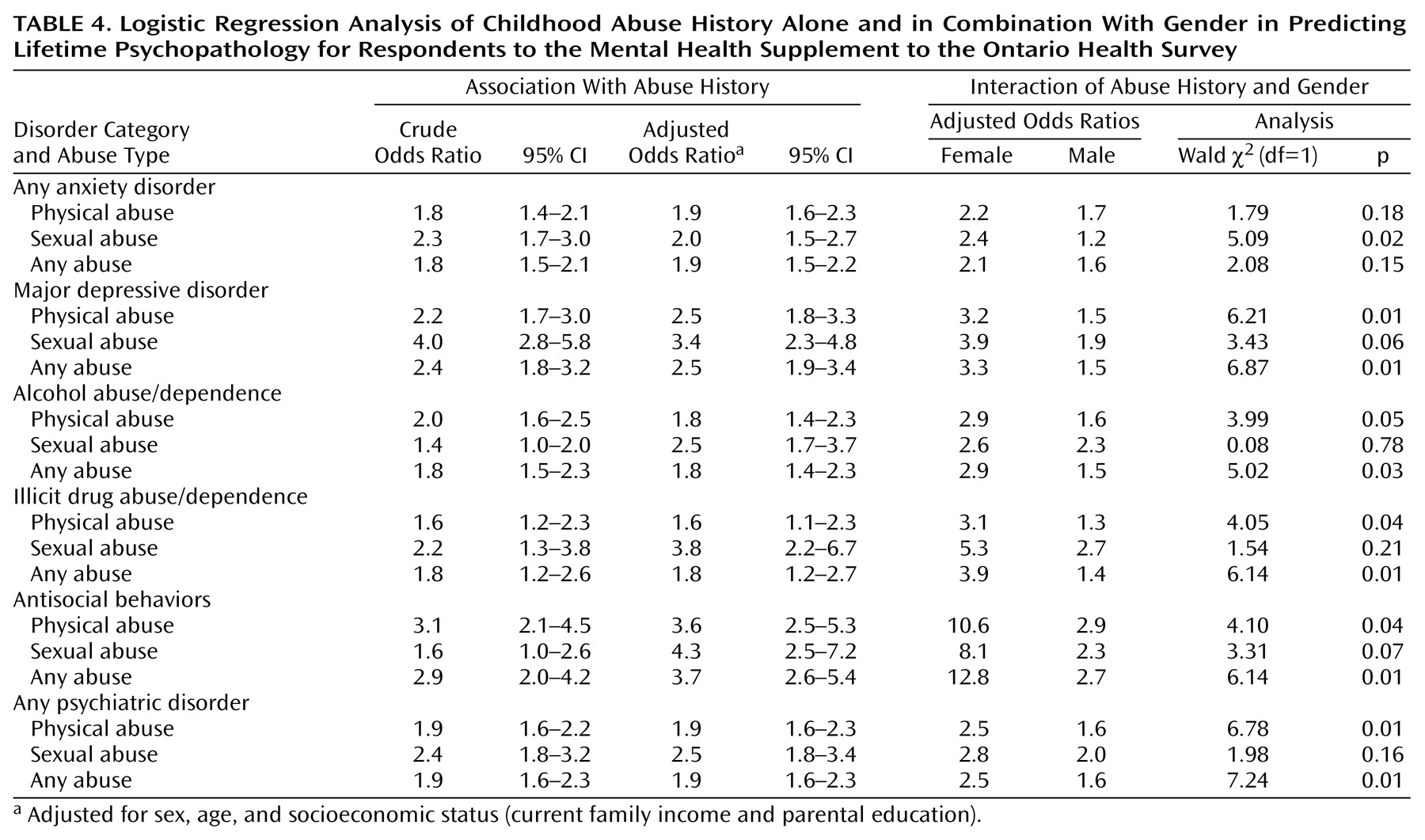

Table 4 presents the crude and adjusted odds ratios from the logistic regression analyses. Adjusting for respondent age, sex, and socioeconomic status had little appreciable impact on the strength of association between exposure to abuse and psychiatric disorder. In every instance the strength of association (odds ratio) between a history of child abuse and psychiatric disorder was larger in magnitude for women than men. For all categories of psychiatric illness except for anxiety disorders, there was a significant interaction with gender for childhood history of both physical abuse and any abuse. Only in the prediction of lifetime anxiety disorders was there a significant interaction with gender for childhood history of sexual abuse, although the interaction approached statistical significance for major depressive disorder and antisocial behavior (

Table 4).

Discussion

This article highlights three main findings from the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey: 1) a history of physical or sexual abuse during childhood is strongly associated with lifetime psychopathology; 2) physical abuse is at least as important a correlate for psychiatric morbidity as sexual abuse; and 3) the relationship between psychiatric illness and history of childhood maltreatment tends to be stronger for women than for men. This survey cannot provide information about cause and effect relationships. As other authors have emphasized, it may not be the history of abuse itself that leads to greater vulnerability for psychiatric illness but rather confounding social and familial factors associated with both the experience of child abuse and greater risk of disorder

(8,

12). These include dysfunctional family environments (associated with both physical and sexual abuse) and poverty (associated with physical abuse)

(24). (While the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey assessed parental education and current family income, it was not possible to assess childhood history of poverty.) A longitudinal study that uses nonabused siblings as control subjects and begins in early childhood before the onset of disorder is a study design that could address these issues.

The Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey relied on retrospective reports to assess the prevalence of a childhood history of physical and sexual abuse. While some suggest that the presence of emotional impairment may influence memory of events, there is little scientific evidence to support the claim that recall of experiences in childhood is altered by psychiatric symptoms or disorder

(25,

26).

The survey findings suggest that childhood physical and sexual abuse are nonspecific correlates of psychiatric illness; there does not appear to be a specific association between either of these subcategories of child maltreatment and one particular psychiatric disorder category. However, one of the most important findings of this study is that the association between a history of child abuse and psychopathology varies by gender. With the exception of anxiety disorders, the relationship between childhood exposure to physical abuse and psychopathology was stronger for women than for men. The relationship between childhood exposure to sexual abuse and psychopathology followed a similar pattern but did not achieve the same patterns of statistical significance because of limited power.

Since many community surveys that have collected information about child maltreatment and psychiatric morbidity have focused exclusively on women

(27), few comparisons are possible. In the supplement to the Los Angeles ECA Study

(9), relative to nonabused subjects, women with a history of childhood sexual abuse experienced higher lifetime rates of all psychiatric disorders except antisocial personality disorder, while abused men had higher rates of substance abuse/dependence. The authors hypothesized that gender differences could be due to the small number of men in the sample or to variations in circumstances of abuse.

Using data from the National Comorbidity Survey

(28), Kessler and colleagues found, among a subsample of respondents who had been exposed to at least one trauma, that women had much higher odds of developing PTSD than men (odds ratio=6.13). Conversely, in a separate article

(14), Kessler and colleagues concluded that there was no systematic sex difference in the associations between childhood adversities (which included such interpersonal traumas as being physically attacked and sexual molestation) and a range of psychiatric disorders (excluding PTSD). These DSM-III-R diagnoses included those examined in the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey.

It is possible that the nature and duration of the reported abuse are dissimilar for men and women. Cutler and Nolen-Hoeksema

(29) suggested that women experience more severe forms of abuse than do men. In the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey, although female and male respondents reported similar rates of severe physical abuse in childhood (9.2% and 10.7%, respectively)

(15), physical abuse was still a stronger predictor of psychiatric illness in women than in men. The survey’s definition of severe physical abuse took likelihood of injury and frequency into account but did not include duration, age at onset of abuse, or relationship with perpetrator, which are some of the factors considered in the sexual abuse literature

(5).

A related issue is the overlap between reports of child physical and sexual abuse. Among female respondents who reported childhood physical abuse, 33% also had a history of sexual abuse, while the corresponding figure for male respondents was only 8%. In contrast, 56% of male and 56% of female respondents who reported childhood sexual abuse also gave a history of physical abuse. Perhaps differences in the degree of overlap between men and women led to differences in the association with psychiatric disorders. Unfortunately, the survey sample was not of sufficient size to examine this issue more closely.

Gender differences in reporting retrospective information about abuse in childhood may have contributed to this effect. An article by Widom and Morris

(30) suggested that among individuals with a history of documented sexual abuse in childhood, far fewer men than women considered their early childhood experiences as sexual abuse.

It is well documented in the literature that both physical and sexual abuse are associated with a range of adverse circumstances

(12). It may be that history of physical or sexual abuse is a marker for other adverse experiences in childhood that are more common among women than men. Since the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey involved retrospective collection of data, detailed information about factors such as family dysfunction or income level while growing up was not available.

Perhaps the experience of physical or sexual abuse in childhood affects women differently from men because of the biological and psychological mechanisms involved in the trauma. Studies examining the impact of child maltreatment suggest that dysfunction of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis may contribute to the development of negative outcomes such as depressive symptoms following exposure to trauma

(31,

32). However, samples to date have generally involved female subjects only

(31) or too few male subjects

(32) to examine the effect of gender. As for psychological mechanisms that may operate differently among men and women, Cutler and Nolen-Hoeksema

(29) suggest that women may be more likely to blame themselves for the abuse or may have a type of affect regulation that increases their vulnerability to negative circumstances. These areas merit further investigation, since understanding differences in risk may assist in developing effective treatments.

Since the Mental Health Supplement to the Ontario Health Survey was a cross-sectional survey, we cannot draw any conclusions about the causal role of childhood maltreatment in the development of psychiatric disorders from these findings. Nevertheless, on the basis of this community survey of more than 7,000 residents of Ontario, both physical and sexual abuse appear to be important markers for a higher likelihood of a range of psychiatric disorders in both men and women.