In DSM-IV, binge eating disorder was introduced as a psychiatric disorder needing further study. The mission of the present study was twofold: to describe the clinical functioning of a community cohort of women with binge eating disorder and to examine the relationship between race and clinical functioning among women with binge eating disorder. To this end, this investigation provides, to our knowledge, the first interview assessment of a community cohort of black and white American women with binge eating disorder.

The clinical literature notes high rates of psychiatric comorbidity and elevated rates of obesity associated with binge eating disorder

(1–

3). In contrast, data from a previous community-based study

(4) found lower rates of psychiatric comorbidity associated with binge eating disorder compared to findings from clinical studies. However, that study did not directly compare community and clinical studies and did not address the role of race in the presentation of binge eating disorder. By directly comparing a community cohort of black and white women with binge eating disorder and a race-matched group of healthy comparison subjects, this study enhances our understanding of binge eating disorder and the role of race in the presentation of binge eating disorder in several important ways. First, until recently, it was widely believed that eating disorders afflicted only individuals who were white, female, and affluent; the well-established literature on the sociocultural influences associated with etiology of eating disorders explains theoretically the limited racial diversity among individuals with eating disorders

(5,

6). However, because binge eating disorder appears more common among diverse ethnic groups, we must revisit some of these assumptions. Second, because most of the existing data on binge eating disorder derive from individuals in treatment, a community study will broaden our understanding of the implications of binge eating disorder for a wider spectrum of individuals.

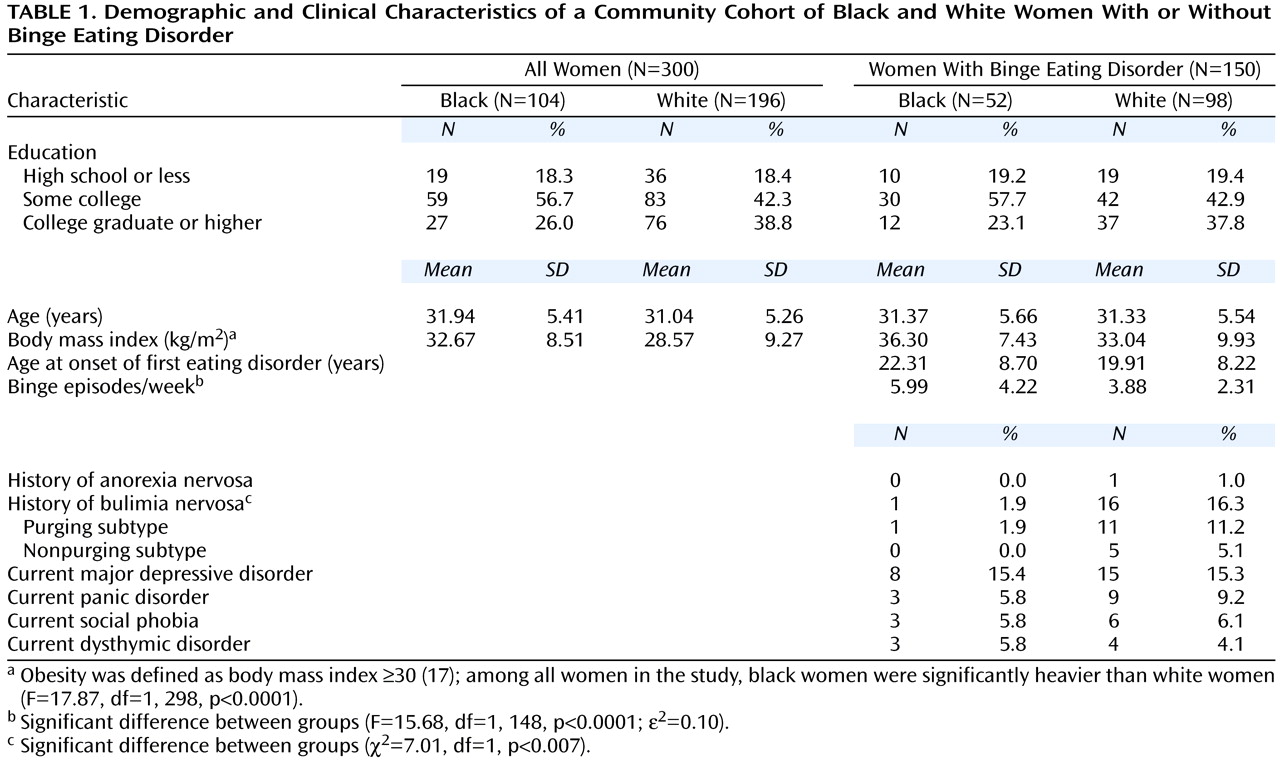

Consistent with current population demographics, it was hypothesized that black women would have higher body mass indexes than white women, regardless of case status

(7). Regarding specific eating pathology, it was hypothesized that black women would report lower rates of weight and shape concerns, regardless of case status, given the greater acceptance of higher weight among black women

(8). By extension, it was hypothesized that black women with binge eating disorder would be comparable to white women with binge eating disorder in terms of the defining behavioral disturbances but report less weight and shape dissatisfaction.

Method

Subjects

The participants included 150 women whose primary diagnosis was binge eating disorder (98 white, 52 black) and a matched group of 150 healthy comparison subjects. The first group met DSM-IV criteria for current binge eating disorder, operationalized as follows: minimum average frequency of binge eating episodes of twice a week for 6 consecutive months, distress over binge eating, presence of three behavioral indicators of loss of control over binge eating, and absence of regular extreme compensatory behaviors. Extreme compensatory behaviors included vomiting; use of laxatives, diuretics, or other drugs for weight control; fasting (eating nothing for 24 hours or more); and excessive exercise (exercising despite pain, against a physician’s advice, or so much that it interferes with responsibilities). Women who reported engaging in extreme compensatory behaviors once a month or more often were excluded from the binge eating disorder group. For this study, binge eating disorder was considered the primary condition for individuals in this group even when comorbid psychiatric conditions were present.

The matched group of healthy comparison subjects were women who did not meet current axis I criteria for any psychiatric disorder and who did not have a history of binge eating or compensatory behaviors once a month or more often or a history of extreme dieting for weight control for 3 or more consecutive months. Comparison subjects were individually matched to patients by race, age, and education.

Recruitment and Procedure

Participants were recruited as part of the New England Women’s Health Project, a community-based study of risk factors for binge eating disorder with project offices in Middletown, Conn., Boston, New York, and Los Angeles. Recruitment began in January 1995 and ended in December 1999. Eligibility criteria for the New England Women’s Health Project included being female, white or black, born in the United States, 18 to 40 years of age, and within driving distance of a project office.

The New England Women’s Health Project used two recruitment strategies. Approximately 10,000 potential participants were contacted through a consumer information database. Individuals were also recruited through posters, newspaper ads, and radio and television announcements for participation in a study of women’s health. There were no racial differences in percentages of women recruited through the consumer information database (white women: 52.0% [N=102 of 196]; black women: 51.9% [N=54 of 104]) or through the advertising campaign (white women: 48.0% [N=94]; black women: 48.1% [N=50]). Most of the women with binge eating disorder were recruited through the advertising campaign (76.7%, N=115), whereas most healthy comparison subjects were recruited from the consumer information database (80.7%, N=121).

Staff phoned all potential participants and determined eligibility for the study by using a 15-minute screening interview developed for the New England Women’s Health Project. Exclusion criteria were age over 40 or under 18 years, physical conditions known to influence eating habits or weight, current pregnancy, presence of psychotic disorder, not being white or black, or not being born in the United States. Women who remained eligible after the telephone screening interview were then interviewed in person and completed several self-report questionnaires. Participants were ensured confidentiality of their responses and were paid for their time. Height and weight were measured and recorded at the end of this interview session. Only instruments used in the present report are described here. This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review boards at Wesleyan University and Columbia University. Informed consent was obtained in two separate steps. For the telephone screening interview, after a complete description of the study, verbal informed consent was obtained from all participants. For the full interview, after a complete description of the study, written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Clinical Information

During the telephone screening interview, participants provided their race, age, and educational attainment. In data analyses, three educational levels were used: high school or less, some college, and college graduate or more. The question about race was asked toward the end of the screening call to reduce the possibility of interviewer bias in ascertaining potential cases of binge eating disorder. Hispanic women were excluded from this study because there were insufficient resources to recruit an adequate sample to study Hispanic women as a distinct group.

The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID)

(10) was used to determine current and lifetime psychiatric status. The reliability and validity of the SCID have been well documented

(11). Staff participated in an initial 60-hour training workshop. Training was continued until individual supervision found 100% agreement between staff ratings and master trainer ratings of three consecutive SCID interviews. Staff participated in ongoing monthly supervision meetings and annual 2-day refresher workshops to avoid interviewer drift.

Participants who met SCID criteria for an eating disorder were interviewed further with the Eating Disorder Examination

(12). The Eating Disorder Examination is a semistructured, investigator-based interview that generates operational eating disorder diagnoses based on DSM-IV criteria. The reliability and validity of this interview are well established

(12). The section that assesses history of binge eating was modified so that the Eating Disorder Examination could be used to confirm eating disorder diagnoses (current and lifetime) and to identify the onset age for eating disorder symptoms and syndromes. Onset age for an eating disorder was defined as the age at which the participant first met all diagnostic criteria. Questions also were added to the Eating Disorder Examination to assess history of treatment for an eating or weight problem. Staff participated in a 40-hour initial training workshop and continued training individually until the master trainer was in 100% agreement with the staff regarding the ratings of three consecutive Eating Disorder Examination interviews. Staff reviewed Eating Disorder Examination tapes in weekly supervision meetings and participated in annual 2-day refresher workshops.

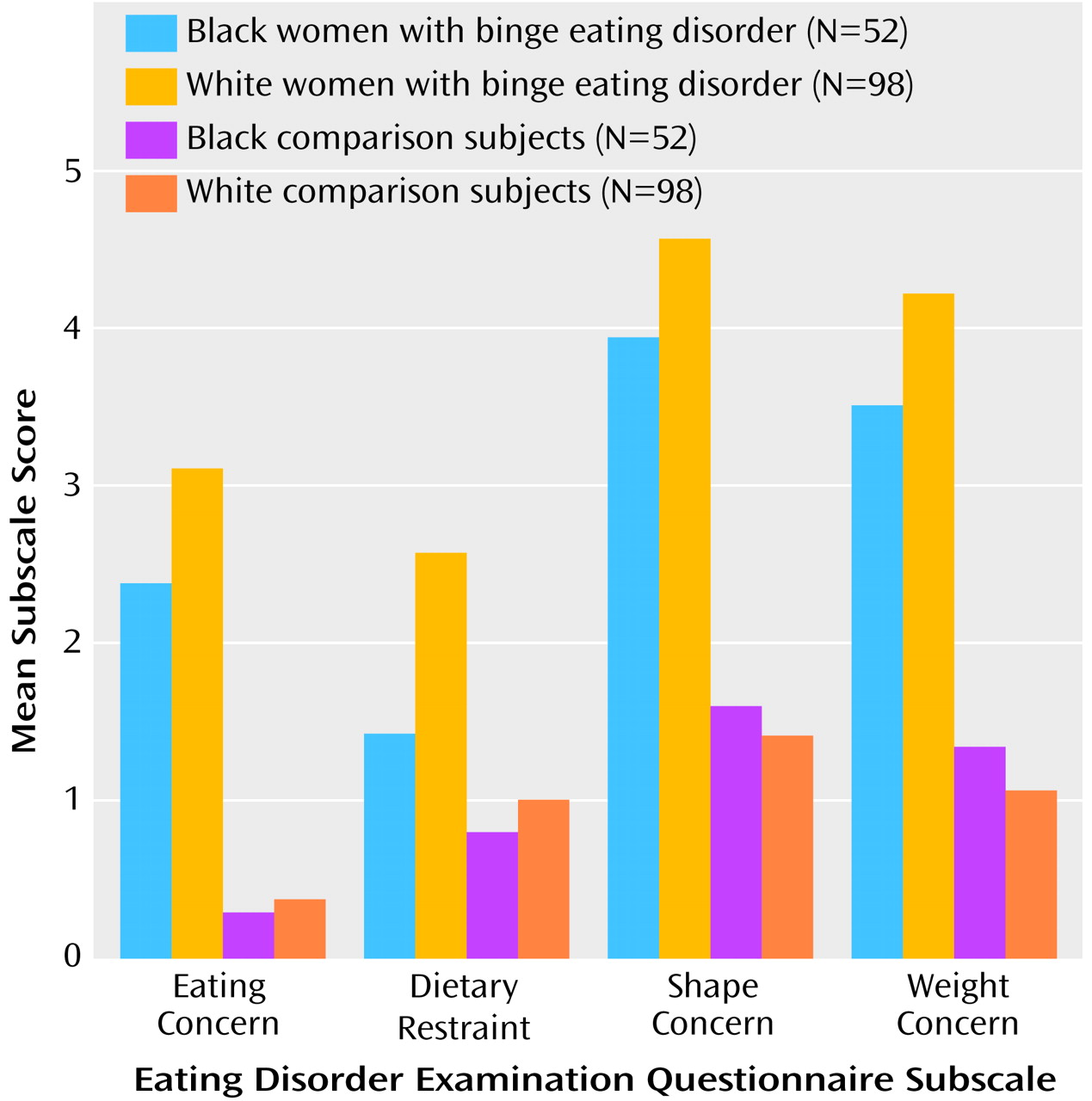

For a continuous assessment of eating disorder symptoms, the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire

(13) was used. Derived from the Eating Disorder Examination, this self-report questionnaire focuses on the past 28 days and assesses shape concerns, weight concerns, eating concerns, and dietary restraint. The Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire has documented reliability and validity

(13–

15).

The Brief Symptom Inventory

(16) is a 53-item instrument that indicates the degree to which an individual has been troubled by specific symptoms during the past 7 days. Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). A Global Severity Index score is calculated by summing across items.

Height (in meters) and weight (in kilograms) were used to calculate body mass index (kg/m

2). Obesity was defined as body mass index of 30 or higher

(17).

Discussion

The results from this study offer a broad picture of clinical functioning related to binge eating disorder among white and black American women in the community. The findings are provocative in that the black and white women with binge eating disorder differed significantly on all associated eating disorder features, including binge frequency, restraint, and concern with eating, weight, and shape. They also differed significantly in terms of history of other eating disorders and seeking treatment for their eating disturbances. These differences occurred despite the fact that all these women met DSM-IV criteria for binge eating disorder according to structured clinical interviews that were further confirmed by the Eating Disorder Examination.

Even though their Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire scores fell within pathological ranges and were significantly greater than those of matched healthy comparison subjects, black women with binge eating disorder reported less concern about body weight, shape, and eating than white women with binge eating disorder. Coupled with higher weight and more frequent binge eating, the clinical binge eating disorder picture for black women is quite different from that of white women. It is of note that the Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire scales did not differentiate between black and white healthy comparison subjects, suggesting that racial differences emerge only at the pathological end of the spectrum of weight, shape, and eating concerns. Given that black culture tends to be more accepting of larger body shapes and less preoccupied with dietary restraint

(6), it appears that black women may be less likely to experience or acknowledge the same degree of attitudinal concern despite significant behavioral symptoms.

The positive relationship of binge eating disorder to body weight and obesity is consistent with results of other studies and underscores the adverse health implications of binge eating disorder. Our results agree with other studies that have documented that black women are heavier than white women whether or not they have an eating disorder

(7). Black and white women with binge eating disorder were equally likely to report having received treatment for a weight problem, but significantly fewer black women with binge eating disorder reported having received treatment for an eating problem. Given the role that binge eating disorder may play in contributing to or maintaining obesity, the fact that black women may be less likely to receive treatment for binge eating disorder presents a significant public health concern.

In our study, only a subset of the women with binge eating disorder reported a history of bulimia nervosa, and such a history was significantly more common in white women. The hallmark feature distinguishing bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder is inappropriate compensatory behavior subsequent to binge eating. These data are compatible with the idea that black women are as much at risk as white women for developing binge eating disorder but, because of cultural differences in concerns about weight and shape, are at less risk than white women for developing bulimia nervosa.

The significant rates of comorbidity associated with binge eating disorder for both black and white women in the community are consistent with clinic data that have suggested that binge eating disorder is a syndrome often linked to affective and anxiety disorders. Black and white women with binge eating disorder reported comparable rates of one current comorbid axis I diagnosis; however, white women were significantly more likely to meet criteria for multiple current axis I disorders and to report higher levels of subjective distress. More research is needed to reconcile the difference in current and lifetime comorbidity. The finding of greater lifetime alcohol and substance abuse among white women than in black women replicates that of larger studies

(20).

The findings from this study have important implications for treatment providers across a range of specialties. Given the apparent relationship between obesity and binge eating disorder

(1), screening for binge eating disorder in obese patients may be indicated. Additionally, although black and white women with binge eating disorder may be equally likely to seek treatment for weight problems, black women in our study were less likely to receive treatment for their eating disorder. This parallels data that indicate, across the entire range of psychiatric disturbances, that the likelihood of receiving mental health care is low for racial minority groups

(18,

21). This low usage of treatment may reflect a cultural bias within the black community regarding mental health care, or there may be other barriers to securing such care. Future studies examining the influence of race on treatment seeking and health care delivery are warranted.

To our knowledge this is the first community-based interview study to assess a cohort of black women with binge eating disorder. It illuminates significant ways in which race plays a role in the clinical presentation of binge eating disorder. One limitation is that, because of the relatively low base rate of the disorder in the population, we were not able to find equal numbers of black and white women with binge eating disorder. These low base rates are a challenge for any community-based study of eating disorders and make investigations of racial differences particularly difficult given the lower proportion of minorities in the broader population. Given these sampling limitations, conclusions drawn from this study should be viewed as tentative until further replication.

The two recruitment strategies revealed important information for future community studies of eating disorders. More cases of binge eating disorder were self-identified through direct recruitment strategies (e.g., advertising campaign) than through the national consumer information database. This likely is a function of the low base rate of binge eating disorder, but it may also reflect some resistance to participating in phone survey research. Women with binge eating disorder may have denied their symptoms or refused to participate in the study when contact was initiated through the consumer database list.

Other interesting issues to explore further are the relationship between race, degree of acculturation, socioeconomic status, and eating disorders. Within a racial minority group, vulnerability to developing an eating disorder may, in part, be a function of socioeconomic status and degree of acculturation. Given the extreme idealization of thinness within white culture, higher socioeconomic status and greater assimilation into white culture in the United States may render black women more vulnerable to developing certain eating and weight disorders

(8). However, drive for thinness may be less central to the etiology of binge eating disorder, and, therefore, socioeconomic status and cultural assimilation as they correlate with binge eating disorder will be important to explore in future studies.

The differences between black and white women with binge eating disorder suggest that distinct racial/ethnic influences need to be considered in studying eating disorder psychopathology. For example, the disturbance pattern for Hispanic women, although generally similar to that of white women, differs in some ways (e.g., increased diuretic use

[22]). Future studies elucidating additional racial/ethnic contributions to the presentation of eating disorders are warranted.

A particular strength of this study is the fact that, to date, it is the largest community interviewer-based investigation of binge eating disorder in North America. Another strength is that we included a healthy comparison group matched by race, age, and education. The comparison allowed us to show that despite racial variation in severity of eating symptoms, both black and white women with binge eating disorder could be differentiated from the healthy comparison subjects. Our data support the notion that binge eating disorder is a clinically significant syndrome in both black and white women. The racial differences in this study suggest the need for research aimed at further elucidating the impact of race on clinical course, health care utilization, and treatment response.