Certainly a clear overlap has been established between conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder

(6,

10–13), and there is evidence to suggest that oppositional defiant disorder precedes conduct disorder in a substantial percentage of cases

(14). However, the majority of children with oppositional defiant disorder do not have conduct disorder

(11), and many children with oppositional defiant disorder exhibit ongoing oppositional behavior without ever developing conduct disorder

(11,

15). Indeed, we have previously shown that subsequent diagnoses of conduct disorder in youth with oppositional defiant disorder are quite infrequent beyond age 6

(11).

An improved understanding of oppositional defiant disorder therefore requires examination of the clinical correlates of the disorder independent of its association with conduct disorder. Such information can strengthen our understanding of oppositional defiant disorder as a meaningful nosological entity and lead to improved treatment approaches aimed at ameliorating the disorder. Toward this end, the purpose of this study was to determine the clinical significance of oppositional defiant disorder alone (i.e., independent of conduct disorder) by examining family interactions, social functioning, and psychiatric comorbidity in a group of clinically referred children with oppositional defiant disorder, either alone or with comorbid conduct disorder, and a group of children with neither disorder.

Discussion

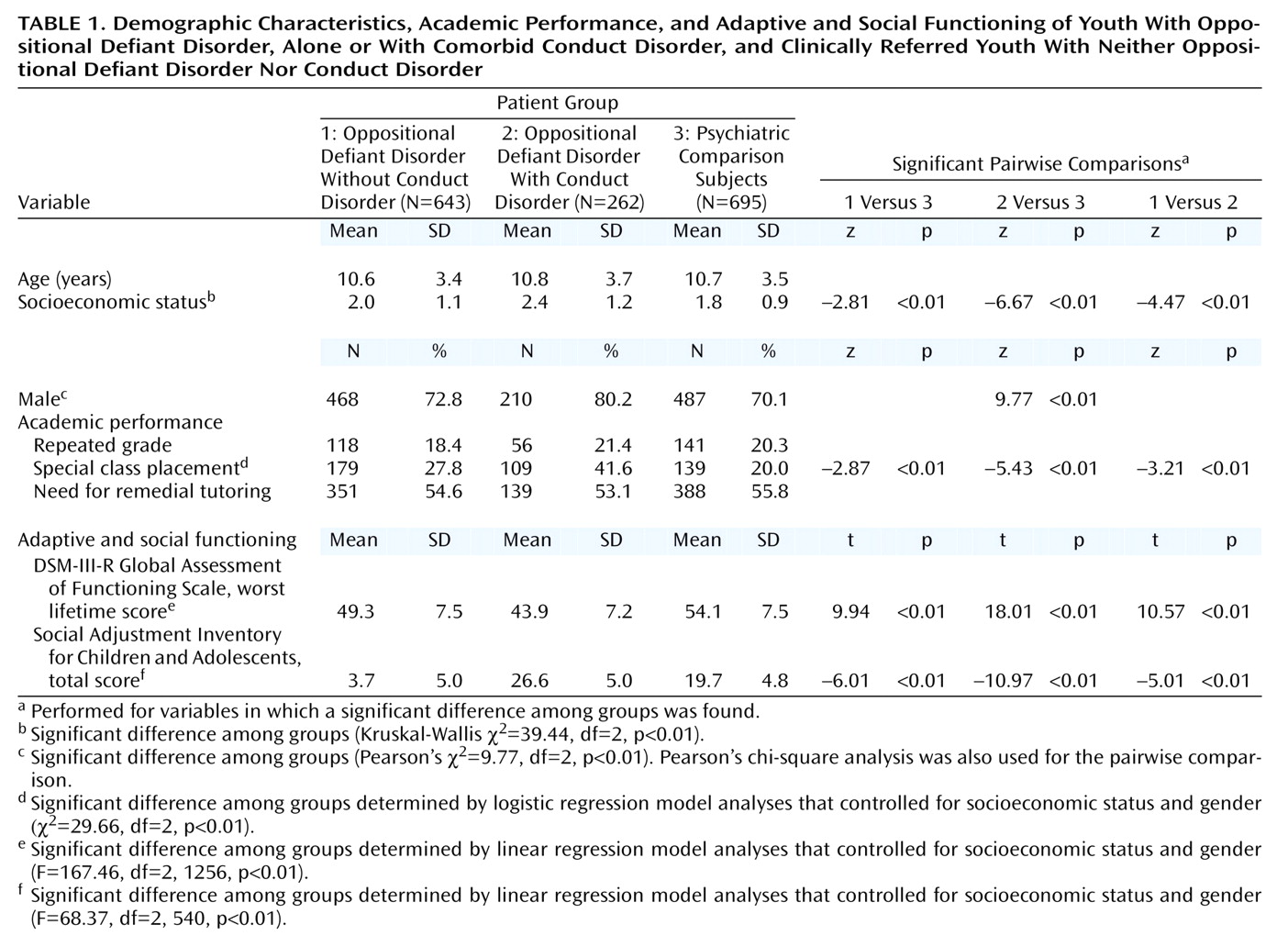

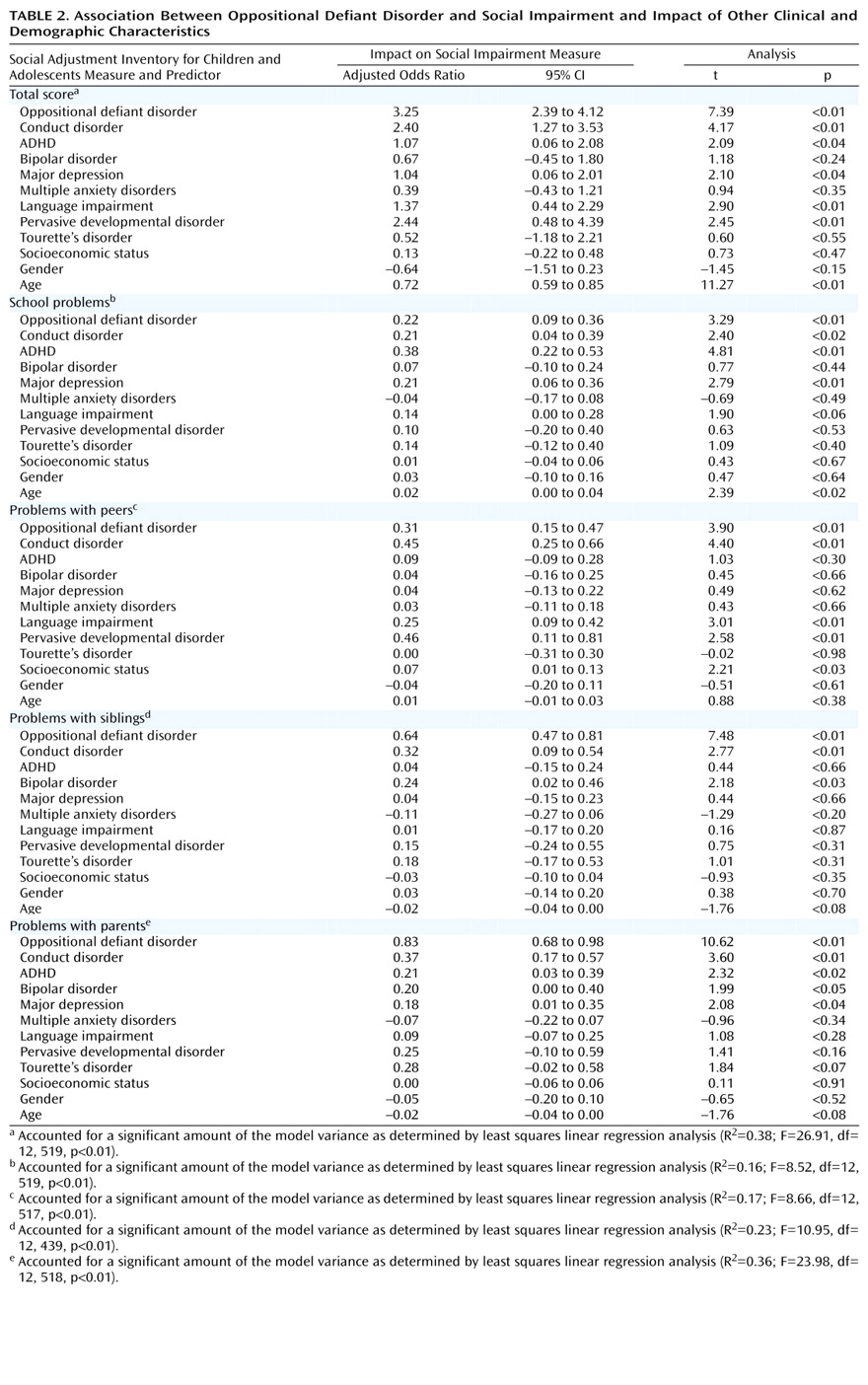

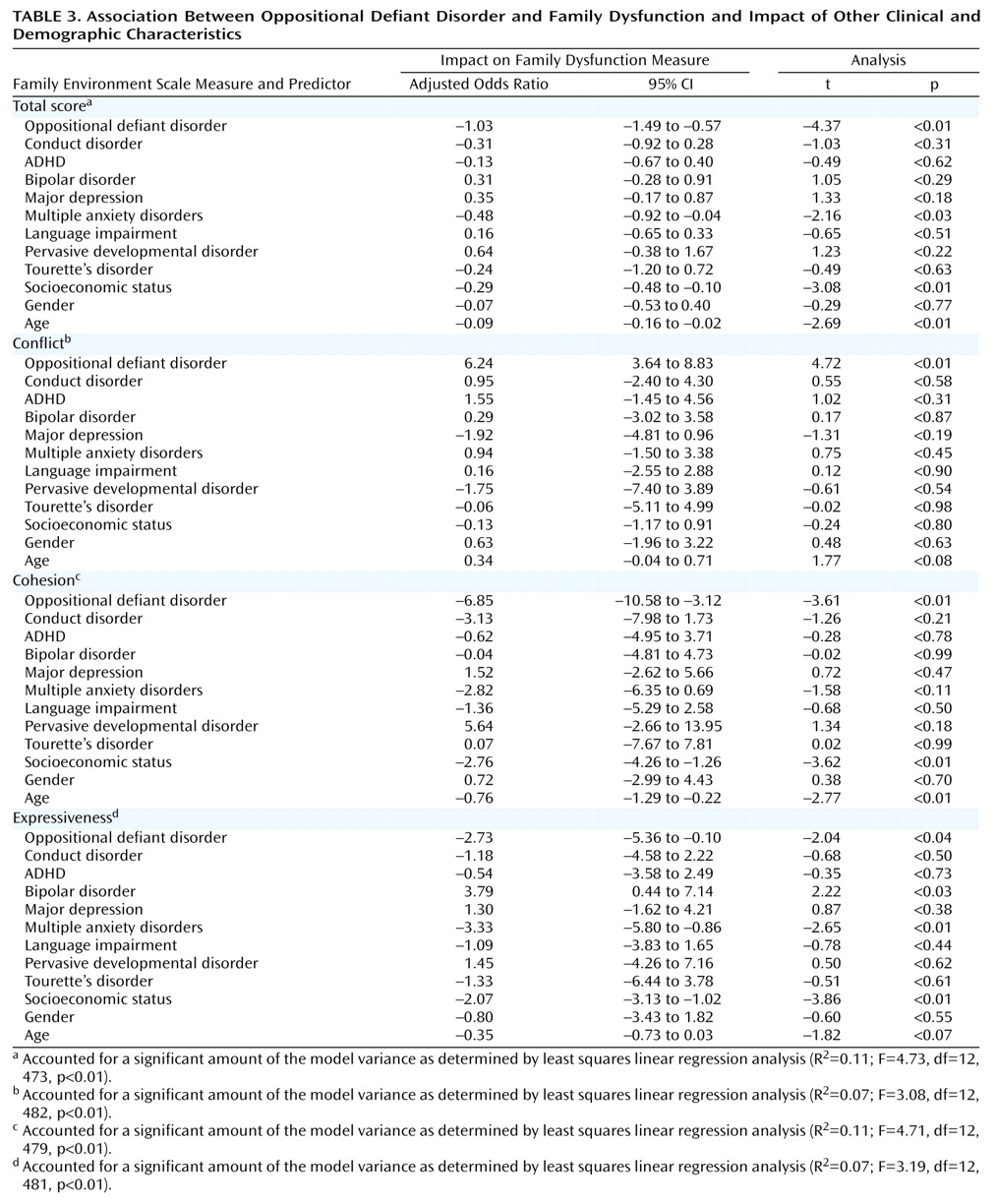

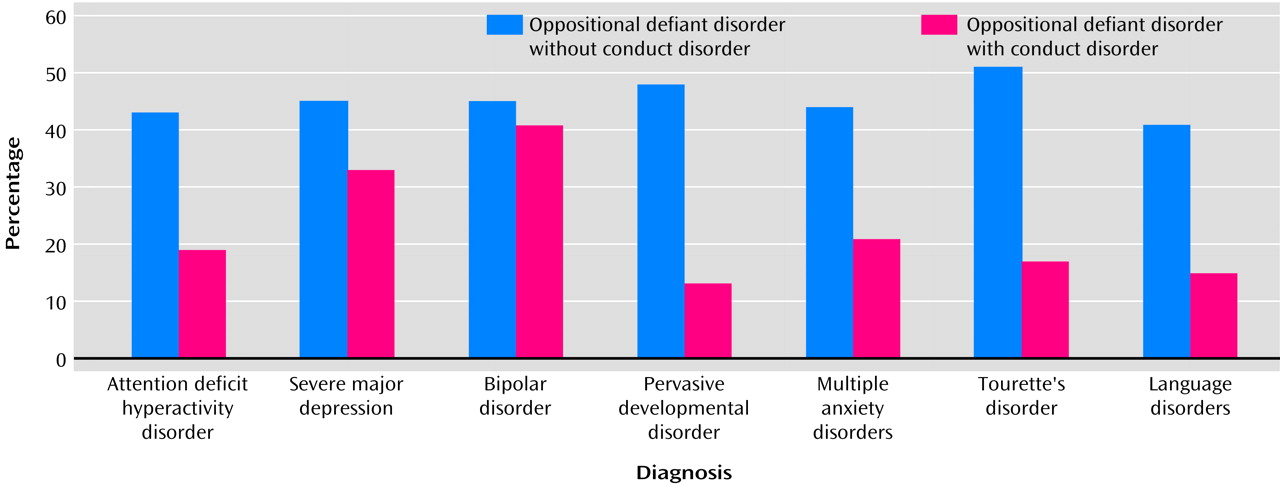

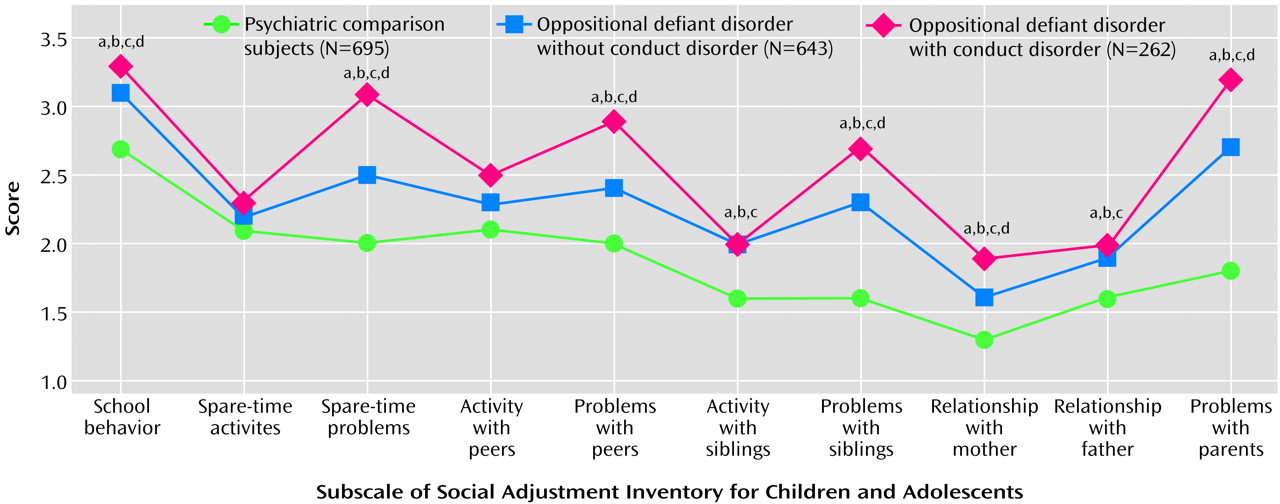

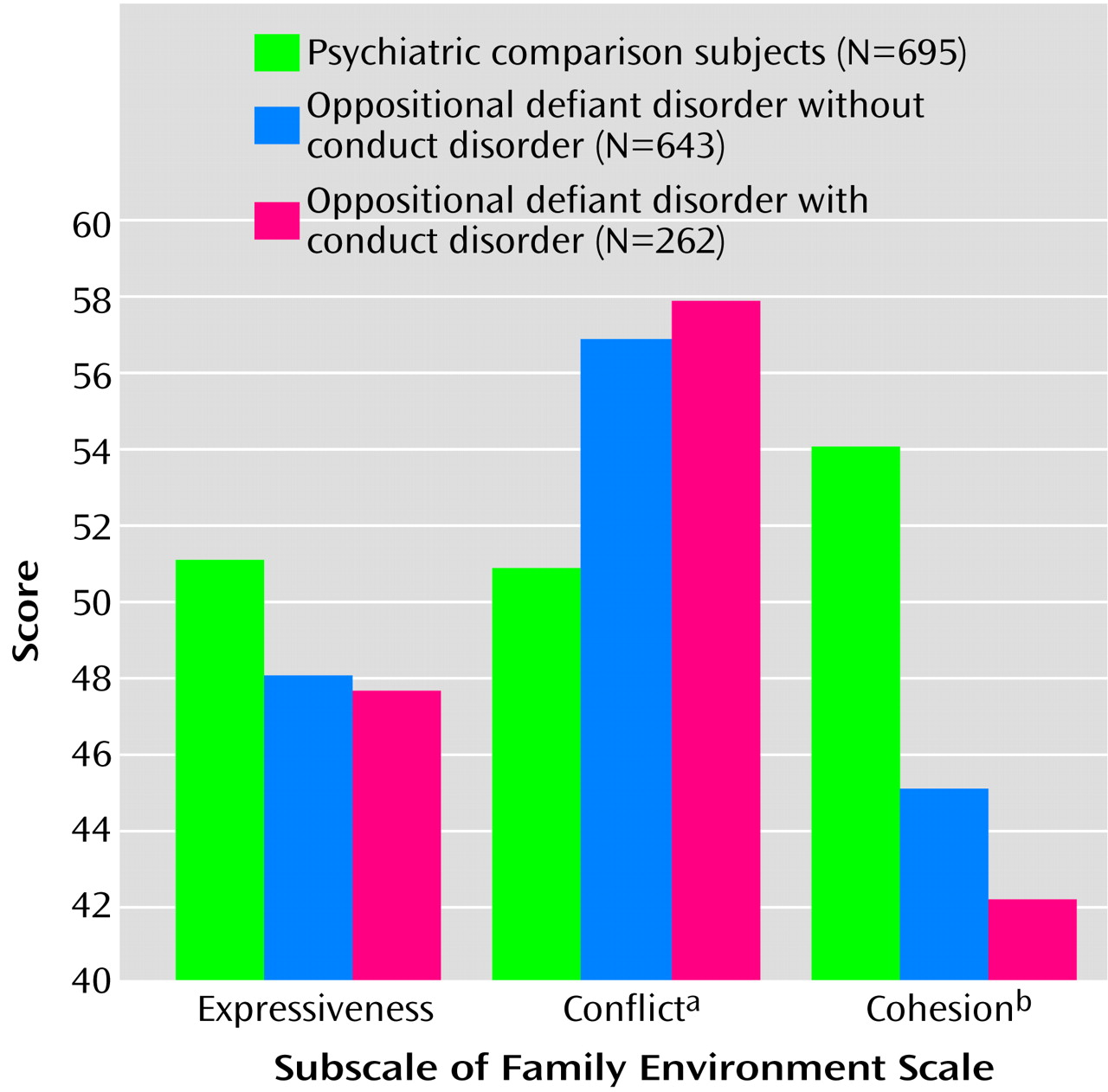

In a carefully diagnosed, large, well-defined group of clinically referred youth, we found that the diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder was associated with significantly higher rates of comorbid disorders, greater social impairment, and greater family dysfunction when compared with a group of clinically referred youth with neither oppositional defiant disorder nor conduct disorder. Specifically, we found that youth with oppositional defiant disorder, either with or without conduct disorder, had significantly lower Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores. In addition, families of oppositional defiant disorder youth with or without conduct disorder were characterized by significantly poorer cohesion and significantly higher conflict. Finally, the significantly impaired social interactions of youth with oppositional defiant disorder cut across all domains of social functioning (i.e., school, parents, siblings, and peers). Oppositional defiant disorder was a consistently significant correlate of these adverse outcomes after we controlled for comorbid conditions, including conduct disorder. Significant differences between youth with oppositional defiant disorder alone or with comorbid conduct disorder emerged primarily in the social domain and in rates of mood disorders. These results support not only the validity of the oppositional defiant disorder diagnosis as a meaningful clinical entity but also the extremely detrimental effects of this disorder on multiple domains of functioning in children and adolescents.

By creating two oppositional defiant disorder groups (i.e., subjects with oppositional defiant disorder alone and those with comorbid conduct disorder) as well as a psychiatric comparison group of subjects with neither disorder, our analyses permitted the examination of the effects of oppositional defiant disorder outside the context of conduct disorder. Clearly, conduct disorder is a serious psychiatric disorder associated with high levels of morbidity. However, the common practice of combining data from oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder groups has obscured the unique correlates and clinical importance of oppositional defiant disorder beyond its association with conduct disorder. Prior studies of children with “conduct problems” have provided valuable information but have not clarified the clinical significance of oppositional defiant disorder in the absence of conduct disorder. The findings reported here show that oppositional defiant disorder contributes to substantial impairment in multiple domains even outside the context of conduct disorder and that this impairment is not accounted for by other psychiatric disorders. Thus, these findings highlight the high clinical and public health relevance of oppositional defiant disorder independent of its association with conduct disorder and underscore the need for further clinical and scientific effort aimed at understanding and ameliorating the adverse outcomes to which this disorder contributes.

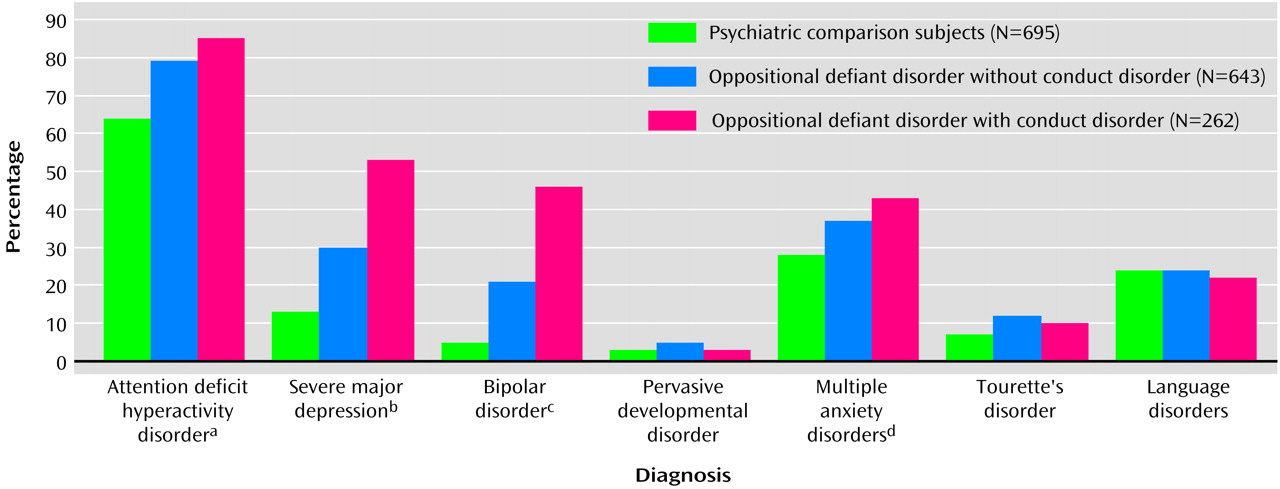

The finding that oppositional defiant disorder is frequently comorbid with ADHD fits with previous research demonstrating significant overlap between the two disorders. Also consistent with prior research, however, is the finding that a meaningful percentage of children with ADHD did not have comorbid oppositional defiant disorder. Our findings documenting an equally large overlap between oppositional defiant disorder and mood and anxiety disorders are also congruent with the limited extant literature. Converging lines of evidence have also suggested that childhood “internalizing” (e.g., mood and anxiety) disorders frequently overlap with oppositional defiant disorder

(11,

25–29). However, these associations between oppositional defiant disorder and other psychiatric disorders have typically been found in research in which the effects of comorbid conduct disorder were not isolated.

Our results suggest that oppositional defiant disorder is a highly heterogeneous disorder with varied presentations, possibly emanating from disparate and complex pathways. These findings have important scientific ramifications as we seek to identify those oppositional defiant disorder children at greatest risk for developing more severe difficulties

(11) and further clarify familial transmission of the disorder

(30). Such findings also have major clinical relevance, since a view of oppositional defiant disorder as a heterogeneous disorder has the potential to heighten awareness of the diverse factors that may contribute to the development of the disorder and raises the possibility that different manifestations of the disorder might require different approaches to treatment. For example, since treatment approaches for ADHD and disorders of mood and anxiety differ, their recognition in children with oppositional defiant disorder may allow clinicians a broader choice of therapeutic options

(9). There is suggestion in the literature that treating symptoms coinciding with oppositional defiant disorder can produce improvements in behaviors related to oppositional defiant disorder as well. For example, in 1999, the Collaborative Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD

(31) reported that stimulant medication produced significant improvements in both ADHD-related and oppositional behaviors. Other research has provided evidence for the efficacy of mood-enhancing medication in children whose oppositional behavior is associated with obsessiveness and irritability

(26). Clearly, characterization and treatment of oppositional defiant disorder on the basis of comorbid presentations is an area worthy of significant research attention.

The high prevalence of oppositional defiant disorder within other clinical populations also deserves additional attention. It has been argued that each of the disorders comorbid with oppositional defiant disorder (e.g., ADHD, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, language impairments) may stem from or contribute to impairments in the domains of affective modulation and self-regulation

(9). Developmental psychologists have long underscored the importance of these two factors with regard to a child’s capacity to adapt to environmental changes or demands and internalize standards of conduct

(32–

35). The skill of compliance—defined as the capacity to defer or delay one’s own goals in response to the imposed goals or standards of an authority figure—can be considered one of many developmental expressions of a young child’s evolving capacities in the domains of adaptation, internalization, self-regulation, and affective modulation

(36). The capacity for compliance is thought to develop in a sequence that includes, in infancy, managing the discomfort that can accompany hunger, cold, fatigue, and pain; modulating arousal while remaining engaged with the environment; and communicating with caregivers to signal that assistance is needed

(35). With the development of language, more sophisticated mechanisms for self-regulation and affective modulation develop, as children learn to use language to label and communicate their thoughts and feelings, develop cognitive schemas related to cause-and-effect, and generate and internalize strategies aimed at facilitating advantageous interactions with the environment

(35). It has been further argued that interventions focused solely on improving a child’s compliance neither target nor effectively treat impairments in self-regulation and affective modulation and that medical and nonmedical interventions aimed at enhancing problem-solving skills, flexibility, and frustration tolerance might be better suited to the needs of many youth with oppositional defiant disorder

(9).

These findings must be interpreted in terms of their clinical significance. In the general population, prevalence rates of the disorders examined in this study tend to be quite low (i.e., below 6%)

(37,

38). Given the very high rates of comorbid disorders in subjects with oppositional defiant disorder, it seems clear that, compared with the general population, oppositional defiant disorder confers clinically significant risk for psychiatric comorbidity. With psychiatric comparison subjects as the reference group, clinically significant differences were most striking within the domain of mood disorders, where oppositional defiant disorder doubled the risk of both severe major depression and bipolar disorder. Oppositional defiant disorder also appears to confer clinically significant risk for social dysfunction compared with both nonclinical populations and psychiatric comparison subjects. Normative data for the Social Adjustment Inventory for Children and Adolescents

(19) suggest that scores for youth with oppositional defiant disorder fall greater than two standard deviations below the mean on most subscales and the total score relative to nonclinical populations. The current data revealed that youth with oppositional defiant disorder fell between one-half and one standard deviation below the mean of psychiatric comparison subjects. With regard to family functioning, normative data for the Family Environment Scale

(24) suggest that youth with oppositional defiant disorder fall between one-half and one standard deviation below the mean for nonclinical populations of children, especially in the domains of conflict and cohesion.

These findings must also be understood in the context of methodological limitations. Cross-sectional data such as those we have reported do not permit examination of longitudinal patterns. For example, given the demonstrated sequential relationship between oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, it is possible that some of the youth with oppositional defiant disorder alone in our study group would subsequently develop conduct disorder. However, we have previously shown that subsequent diagnoses of conduct disorder in youth with oppositional defiant disorder are quite low beyond age 6

(11). Given the mean age of our study group (10.8 years), we would anticipate that very few of the youth with oppositional defiant disorder alone in this data set would subsequently develop conduct disorder.

Our subjects were clinically referred and consisted primarily of Caucasian youth; thus, our results may not generalize to other groups of oppositional defiant disorder children. For example, our finding that oppositional defiant disorder is associated with significant comorbidity differs dramatically from one recent study

(13), presumably because of important study group differences (subjects in the current study were both significantly older and clinically referred). Further, our data were obtained predominantly from mothers. While multiple informants provide a broader examination of a child’s functioning, in prior studies we have shown significant overlap between information gathered from mothers and other reporters

(39). Finally, the findings we have described are cross-sectional; further study is required to examine the long-term sequelae of oppositional defiant disorder.

Despite these limitations, in a carefully assessed group of clinically referred youth, children with oppositional defiant disorder evidenced significantly higher rates of comorbidity and significantly greater impairment in adaptive, social, and family functioning than did children without oppositional defiant disorder, and oppositional defiant disorder was a significant correlate of such impairment even after we controlled for a wide range of comorbid conditions and demographic characteristics. These results support the validity of oppositional defiant disorder as a meaningful clinical entity independent of conduct disorder and warrant additional study of children and adolescents who are so diagnosed and a broadened examination of diverse approaches to treatment aimed at ameliorating their difficulties.