Estrogen has been reported to stabilize mood, reduce psychotic symptoms, and limit aggressive behavior

(1–

3). In some studies, estrogen has improved or delayed the onset of various aspects of cognitive decline

(4,

5). Estrogen, compared to placebo, was associated with less aggression in moderately to severely demented elderly patients in a 4-week randomized trial

(3). We now provide additional data from this double-blind trial on the effects of conjugated equine estrogens on noncognitive signs and symptoms of dementia, as assessed by the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale

(6).

Method

Study entrants were 14 women and two men with moderate to severe dementia and aggressive behavioral disturbances. Inclusion criteria were age over 60 years, dementia diagnosed with DSM-III-R/DSM-IV, and recent history of three or more aggressive incidents per day. Because of the advanced state of illness and long-standing dementia diagnoses, comprehensive dementia workups were not performed and more specific dementia diagnoses could not be made. Principal exclusion criteria were acute major affective or psychotic illness (including acute psychosis due to dementia), history of breast or endometrial cancer, acute thromboembolism, thrombophlebitis, pulmonary embolism, estrogen use within 1 month before starting the study, or adverse effects from prior estrogen use

(3). Written informed consent was obtained from the patient or responsible family member after study procedures were fully explained.

Detailed study methods were described previously

(3). Briefly, subjects were randomly assigned to receive estrogen or placebo in a double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Baseline and weekly assessments included use of the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale, a modified Overt Aggression Scale

(7), and mental status and physical examinations.

Patients randomly assigned to receive estrogen took 0.625, 1.250, 1.875, and 2.500 mg/day of conjugated equine estrogens over weeks 1 through 4, respectively. Control subjects received placebo on days 1 through 28. Two estrogen and three placebo patients continued taking the maintenance psychotropic medications that they were taking at study entry.

The principal outcome measure was change in baseline score on the 43-item Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale. The Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale, with five subscales rating anxiety, mania, depression, behavior, and delusions, hallucinations, or illusions, contains a total of 129 points (43 items scored 0–3, examiner’s composite ratings)

(6). Higher scores on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale indicate greater signs and symptoms. The developers of this scale reported excellent interrater reliability and validity

(6).

Intent-to-treat methods were used, with Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale total scores analyzed as change from baseline values. Covariates included baseline score on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale, Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores

(8), modified Overt Aggression Scale scores, and age. Methods based on generalized estimating-equation modeling, with adjustment for clustering within patients and robust estimation of standard errors, were used for comparison of effects of estrogen versus placebo

(9). In this application, generalized estimating-equation methods were used to carry out a random effects, repeated-measures analysis with time (week) and group (estrogen or placebo) as the main effects. Spearman’s rank-based correlation (r

s) methods were used to assess associations between scores on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale and the MMSE, the modified Overt Aggression Scale, and age. As the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale analyses were post hoc secondary analyses, multiple-comparison step-down Holm-Bonferroni adjustments were made

(10). Averaged continuous data are reported as means with standard deviations. Comparisons with two-tailed p>0.05 at stated degrees of freedom were considered nonsignificant.

Results

Of 59 subjects screened, 16 (estrogen group: seven women and one man; placebo group: seven women and one man) entered the trial, and 15 (13 women and two men) completed the trial. One placebo subject dropped out at week 1 because of severe tardive dyskinesia. Mean age was 83.4 years (SD=6.9) (estrogen group: mean=81.0 years, SD=3.7; placebo group: mean=85.8 years, SD=8.8). All were Caucasian and had a mean 10 years of education (SD=5) (estrogen group: mean=10.7 years, SD=2.3; placebo group: mean=8.7 years, SD=4.4). All patients met DSM-III-R/DSM-IV dementia criteria. The average baseline total score on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale was 31.7 points (SD=8.5) (estrogen group: mean=31.6 points, SD=8.7; placebo group: mean=31.7 points, SD=9.0) out of a possible 129. The average baseline MMSE score was 4.9 points (SD=7.7) (estrogen group: mean=4.1 points, SD=6.8; placebo group: mean=5.7 points, SD=9.0) out of a possible 30.

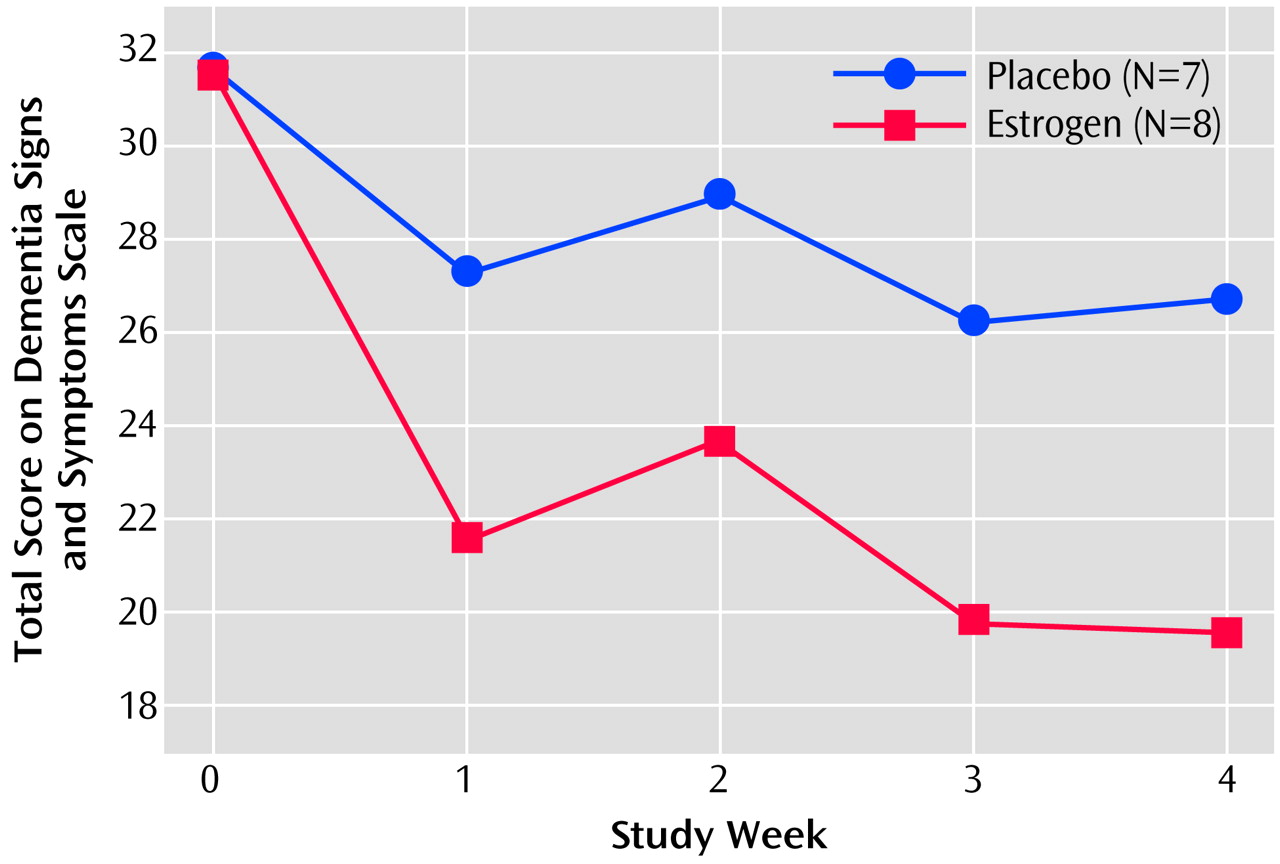

At endpoint, the mean score of the estrogen group on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale was 19.6 (SD=6.5), 38% lower than the baseline mean of 31.6 points (SD=8.7). For the placebo group, the mean baseline score on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale was 31.7 (SD=9.0); the endpoint score was 26.7 (SD=12.0)—a decline of 16%. This 2.4-fold difference of 38% versus 16% change in score was statistically significant after adjustment for baseline scores (z=–2.26, N=15, p<0.03; p<0.05, with step-down Holm-Bonferroni adjustment) (

Figure 1).

In multivariate analyses with time (week) and group (estrogen or placebo) as main effects, time-by-drug (placebo) interaction effects were not significant. Total scores on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale for the estrogen and placebo groups declined in parallel over the last 3 weeks of the study. Covariate adjustment of baseline scores on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale, weekly MMSE scores, and age did not alter the significant difference between the estrogen and placebo groups in change in score on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale.

On all five Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale subscales, mean scores substantially decreased more over the 4-week trial in the estrogen subgroup than in the placebo subgroup, suggesting clinically significant effects. Mean percentage change from baseline on the five Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale subscales were as follows: 1) delusions, hallucinations, illusions subscale: estrogen, –40%, placebo, +65%; 2) anxiety subscale: estrogen, –27%, placebo, +59%; 3) mania subscale: estrogen, –29%, placebo, +26%; 4) depression subscale: estrogen, –43%, placebo, –24%; 5) abnormal behavior subscale: estrogen, –32%, placebo, –30%.

There were no correlations between total or subscale scores on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale and MMSE scores or age at baseline or in subsequent weeks. Total change scores on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale were uncorrelated with change scores on the modified Overt Aggression Scale (rs=0.09, N=15, p<0.52), suggesting that changes in aggressive behaviors and in noncognitive signs and symptoms of dementia assessed by the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale may be affected independently by estrogen therapy. The analyses were repeated with omission of the two male subjects; the results were the same.

Discussion

The change data reported here on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale suggest that conjugated equine estrogens may decrease the frequency and severity of noncognitive signs and symptoms of dementia in moderately to severely demented elderly patients. Differences in scores on the Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale in the patients receiving estrogen and those receiving placebo appeared early, within the first week for most patients, with the scores of the estrogen and placebo groups remaining essentially parallel after that. The differences were found to be uncorrelated with MMSE score, aggressiveness, or age. Changes in aggressive behaviors were uncorrelated with changes in Dementia Signs and Symptoms Scale subscale scores, suggesting that estrogen may affect dementia patients’ behaviors diversely, improving aggressiveness in some patients and other noncognitive signs and symptoms of dementia in other patients.

Study limitations include the small group size and brief trial duration. An optimal estrogen dose was not identified; conjugated equine estrogen doses were increased weekly. Further controlled clinical trials with larger group sizes and extended over longer durations are needed to affirm these findings.

In summary, to our knowledge, this preliminary study provides the first clinical evidence based on randomized clinical trial data that conjugated equine estrogens in oral doses ranging from 0.625 to 2.500 mg/day can potentially decrease the frequency and severity of noncognitive signs and symptoms of dementia in elderly patients with dementia.