The thalamus comprises multiple nuclei that relay and filter sensory and higher order inputs to and from the cerebral cortex and limbic structures

(1). Deficits in the frontal lobes, temporal lobes, and the striatum have been found in schizophrenia in both structural and functional imaging studies; these findings are reviewed elsewhere

(2,

3). Since each thalamic subdivision has a unique reciprocal circuitry with these affected cortical and subcortical areas

(4), separate assessment of these nuclei is important. Three nuclei visible on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans—the mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, and the centromedian nucleus—are of particular interest in schizophrenia because of their reciprocal connections with the frontal, temporal, and basal ganglia regions that show schizophrenia-related abnormalities.

The mediodorsal nucleus is activated in tasks involving memory and attention

(5,

6). It has interconnections with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex

(7), a key area of functional and structural alteration in schizophrenia

(3,

8). Until the mid-1970s it was thought that the prefrontal cortex received its thalamic input solely from the mediodorsal nucleus; however, it is now apparent that the pulvinar also contributes to its innervation

(9,

10). The pulvinar, important in visual and possibly auditory attention

(11,

12), also has prominent interconnections with the temporal lobe, a second area of morphometric

(2,

13) and functional change

(14–

16) in schizophrenia. Last, the centromedian nucleus, one of the intralaminar nuclei, directly influences the sensorimotor and premotor cortices

(17), as well as the prefrontal cortex

(18). Lesions of the intralaminar nuclei produce signs of attentional impairment and executive dysfunction similar to those observed with frontal cortical damage

(19). This pattern of connectivity suggests that lower levels of activity of the centromedian nucleus might decrease activity in striatal and thalamocortical circuitry and result in less cortical activation. Schizophrenia-associated abnormalities of the mediodorsal nucleus

(20–

24), pulvinar

(20,

21), centromedian nucleus

(21), ventral posterior nucleus

(25), and anterior nucleus

(26) have been demonstrated in postmortem studies. The importance of the thalamus for attentional processing, a key psychological deficit in schizophrenia, led to the early hypothesis that the etiology of schizophrenia might be related to a defect in brain circuitry involving three nuclei of the thalamus (mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, and centromedian nucleus) and the goal-oriented prefrontal cortex

(27). Crosson

(28) suggested that the mediodorsal nucleus is a critical element in an attentional “selective engagement” system that affects semantic functions in schizophrenia. Andreasen

(8) postulated that the “cognitive dysmetria” of schizophrenia results from an abnormality in the prefrontal-thalamic-cerebellar circuitry.

Using a coregistered MRI template to trace the thalamus, we found relatively lower levels of glucose metabolism in the region of the mediodorsal nucleus in blinded ratings of never-medicated schizophrenia patients and healthy comparison subjects

(29). With the increased resolution of positron emission tomography (PET) (4.5-mm full width at half maximum) and the coregistered structural MRI, we confirmed lower relative glucose metabolism in the region of the mediodorsal nucleus in unmedicated schizophrenia patients, compared with healthy volunteers, while whole thalamus metabolic rates did not differ between groups

(30). In an [

18F]-deoxyglucose (FDG) PET study, a relatively lower metabolic rate in the whole thalamus was found in patients with schizophrenia, compared with healthy subjects

(31). During a novel memory task in a study using [

15O]H

2O PET, patients showed less regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) in the right thalamus, compared with healthy subjects

(32). Others have also reported lower rCBF in the right thalamus during word recognition in patients, compared with healthy subjects, while task performance did not significantly differ between the groups

(14). Heckers et al.

(33) reported attenuated right thalamic activation in schizophrenia patients in the pulvinar region of the right thalamus during a visual object recognition task. A functional MRI (fMRI) study reported less activation in the left thalamus during a sustained attention task in medicated schizophrenia patients, compared to healthy subjects

(34), while another study reported greater activation during a working memory task in patients, compared with healthy subjects

(35). Higher rCBF was found in the pulvinar (Talairach

[36] coordinates x=–12, y=–25, z=6) in patients with chronic schizophrenia

(37), as well as in neuroleptic-naive patients (coordinates x=13, y=–22, z=18) (see reference

38).

PET with FDG provides a method for assessing the uptake of glucose into the brain as an index of regional metabolic activity. FDG is taken up in a manner similar to glucose but is metabolically trapped as a marker in a 30–40-minute period during which a behavioral task can be carried out. The patient is then moved to the scanner, and a series of slice images of FDG localization are obtained with the multiple rings of the scanner surrounding the head. To our knowledge, there is no published report on relative glucose metabolism in thalamic nuclei traced from coregistered MRI scans. We hypothesized that 1) schizophrenia patients have less relative glucose metabolism in these three subdivisions of the thalamus (mediodorsal nucleus, centromedian nucleus, and pulvinar), compared with healthy subjects; 2) greater dysfunction in these nuclei is associated with greater symptom severity and poorer memory performance; and 3) relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal nucleus is an independent contributor to determinations of group membership.

Method

Subjects

Forty-one patients with schizophrenia (32 men, nine women; mean age=36.9 years, SD=15.2, range=18–73; 36 right-handed subjects) were recruited. The patients were evaluated with the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History

(39) and received a diagnosis of either schizophrenia (N=37) or schizoaffective disorder (N=4) according to DSM-IV criteria. The patients either had never been medicated (N=15) or had been neuroleptic free for a minimum of 2 weeks (N=26). Their total psychopathology scores on the 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)

(40) ranged from 25 to 89 (mean=52.4, SD=12.7, median=51). Sixty healthy volunteers (45 men, 15 women; mean age=40.1 years, SD=15.9, range=20–81; 58 right-handed subjects) received a Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History interview to exclude those with psychiatric illness in themselves or in their first-degree relatives.

All participants were screened by medical history, physical examination, and laboratory testing. Individuals with a history of substance abuse/dependence, neurological disorders, or head trauma and those with a positive urine test for drugs of abuse on the day of the PET scan were excluded. After a complete description of the study, all participants provided written informed consent. Volumetric data

(21,

41) and PET data (relative glucose metabolism in the whole thalamus

[30]) from a subset (N=27 patients and N=32 healthy subjects) of the scans have been reported earlier.

PET FDG Uptake Task and Procedure

Before the procedure, participants were read standard instructions about the serial verbal learning task

(42), which was developed for the 32-minute FDG uptake period and is analogous to the California Verbal Learning Test

(43). Scores were recorded for total number of correctly recalled words, recall by semantic clustering, recall by serial ordering, intrusions (words not in the list), and perseverations (repetition of a correct word on the same trial).

PET and MRI Acquisition

PET scans (20 slices, 6.5-mm thickness) were obtained

(30) with a head-dedicated scanner (General Electric model PC2048B) (General Electric, Milwaukee) with measured resolution of 4.5 mm in plane (range=4.2–4.5 mm across 15 planes). T

1-weighted axial MRI scans were acquired with the GE Signa 5x system (General Electric, Milwaukee) (TR=24 msec, TE=5 msec, flip angle=40°, slice thickness=1.2 mm, pixel matrix=256×256, field of view=23 cm, total slices=128).

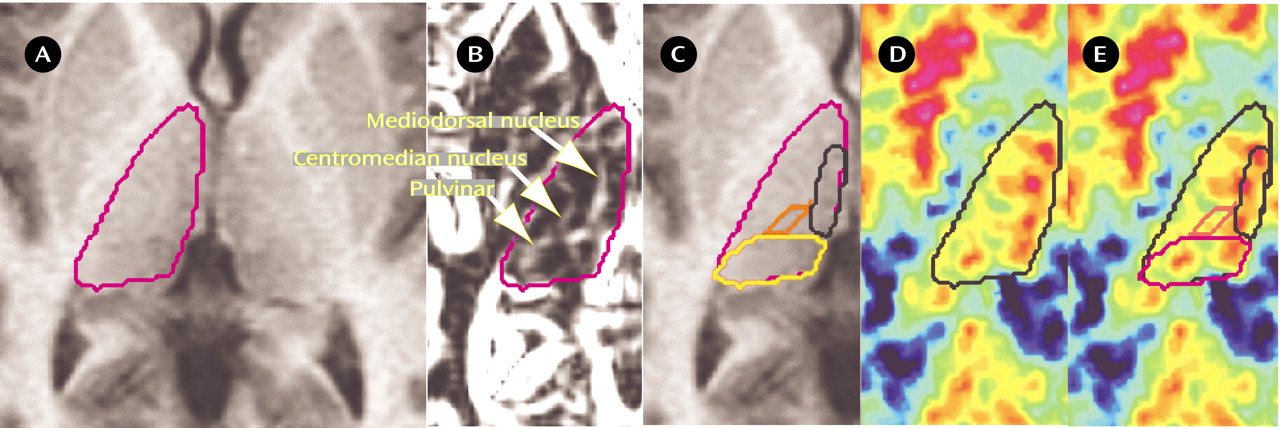

PET and MRI Coregistration and Thalamic Tracing

The PET and MRI scans were obtained in the axial plane (canthomeatal line) by using the same individually molded thermoplastic head holder for both procedures. PET images were coregistered to the MR images by using brain slice edges described in detail elsewhere

(44). The edges of the thalami and thalamic nuclei were traced on contiguous 1.2-mm axial MR images by using a method with demonstrated intertracer reliability that we have used previously

(41) (

Figure 1).

Design and Statistical Analysis

This study used a two-by-three-by-two (group by thalamic nuclei by hemisphere) mixed factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) design. We report both univariate F and multivariate Rao’s R to control for inflated degrees of freedom. As follow-up to significant interaction effects, simple interactions were evaluated for each key factor (e.g., nucleus). Pearson product-moment correlations were used for all correlational analyses.

Results

Center-of-Mass Analysis for Relative Glucose Metabolism in the Thalamic Nuclei

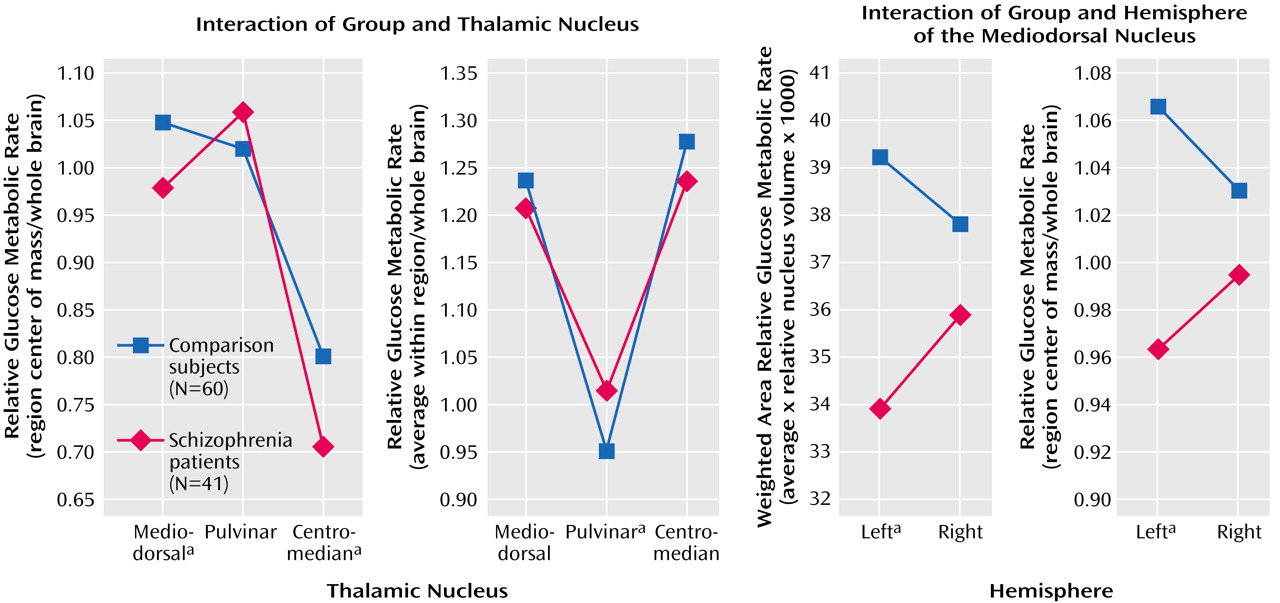

The group (healthy comparison subjects, schizophrenia patients)-by-thalamic nuclei (mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, or centromedian nucleus)-by-hemisphere (left, right) mixed-design ANOVA for relative glucose metabolism confirmed a significant group-by-thalamic nuclei interaction indicating that patients had lower relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal and centromedian nuclei, but not in the pulvinar (F=7.46, df=2, 198, p=0.0008; Rao’s R=10.03, df=2, 98, p=0.0001;

Figure 2, leftmost panel). The main effect of group was also significant, indicating that patients had lower overall relative glucose metabolism averaged across the three nuclei and both hemispheres (patients: mean=0.91, SD=0.15; comparison subjects: mean=0.96, SD=0.17; F=4.63, df=1, 99, p<0.04). The main effects for thalamic nuclei and hemisphere, as well as the interaction of thalamic nucleus and hemisphere, also reached significance (p≤0.002), but none of the other interactions with group was significant.

Two-way ANOVAs for each of the three thalamic nuclei were used to follow up the significant group-by-thalamic nuclei interaction effect. For the mediodorsal nucleus (

Figure 2, leftmost panel), there was a significant main effect of group indicating that patients had lower relative glucose metabolism averaged across the left and right hemispheres in the mediodorsal nucleus, compared with the healthy subjects (patients: mean=0.98, SD=0.14; comparison subjects: mean=1.05, SD=0.17; F=6.13, df=1, 99, p<0.02). The group-by-hemisphere interaction was also significant (F=4.56, df=1, 99, p<0.04;

Figure 2, rightmost panel), indicating that the healthy subjects had higher relative glucose metabolism in the left mediodorsal nucleus compared with the right, while the patients showed the opposite pattern. Follow-up simple effects tests indicated that the patients showed lower relative glucose metabolism in the left mediodorsal nucleus, compared with the healthy volunteers (F=10.58, df=1, 99, p<0.002), but glucose metabolism in the right mediodorsal nucleus was not significantly different between groups (p=0.27).

The follow-up ANOVA for the centromedian nucleus showed a significant main effect for group indicating that the patients had significantly less relative glucose metabolism in the centromedian nucleus, compared with the healthy subjects, averaged across the left and right hemispheres (patients: mean=0.71, SD=0.16; comparison subjects: mean=0.80, SD=0.19; F=9.48, df=1, 99, p<0.003). The follow-up ANOVA for the pulvinar failed to reach significance for the main effect of group or the group-by-hemisphere interaction (all p>0.05).

Average Relative Glucose Metabolism in the Thalamic Nuclei

A parallel set of ANOVAs was performed to analyze average relative glucose metabolism for all pixels within the region-of-interest outlines. The group (healthy comparison subjects, schizophrenia patients)-by-thalamic nuclei (mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, or centromedian nucleus)-by-hemisphere (left, right) ANOVA for average relative glucose metabolism within the region of interest yielded a significant interaction of group and thalamic nucleus (F=8.63, df=2, 198, p=0.0003; Rao’s R=11.36, df=2, 98, p<0.00001;

Figure 2, second panel from the left). This interaction effect indicated that patients had lower relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal and centromedian nuclei but higher relative glucose metabolism in the pulvinar. The main effect for group and other interactions with group failed to reach significance. The follow-up ANOVA for the pulvinar showed a significant main effect for group indicating that the patients had higher relative glucose metabolism averaged across the left and right hemispheres in the pulvinar, compared with the healthy subjects (patients: mean=1.03, SD=0.13; comparison subjects: mean=0.96, SD=0.13; F=6.73, df=1,99, p<0.02). The follow-up ANOVA for average relative glucose metabolism in the centromedian nucleus failed to reach significance for the main effect of group or the group-by-hemisphere interaction (both p>0.05).

Weighted Area Relative Glucose Metabolism in the Thalamic Nuclei

Weighted area relative glucose metabolism for each of the thalamic nuclei was computed, as described previously

(29), by using the following formula: average relative glucose metabolism within nucleus × total thalamic volume for same nucleus/whole brain volume × 10,000. Next, we conducted a parallel set of ANOVAs to analyze the weighted area relative glucose metabolism. The group-by-thalamic nucleus (mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, centromedian nucleus)-by-hemisphere ANOVA yielded a significant main effect for group, indicating that the patients had lower weighted area relative glucose metabolism across the three nuclei and the two hemispheres (F=4.29, df=1, 99, p<0.05). There were no group interactions. However, because we had specific hypotheses about the mediodorsal nucleus, we conducted separate ANOVAs to analyze the data for each of the three nuclei.

Mediodorsal nucleus

A main effect of group indicated that schizophrenia patients had significantly lower weighted area relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal nucleus, compared with the healthy subjects (patients: mean=34.88, SD=6.62; comparison subjects: mean=38.49, SD=7.89; F=7.64, df=1, 99, p<0.007). There was also a significant group-by-hemisphere interaction reflecting greater relative glucose metabolism in the left mediodorsal nucleus, compared with the right, in the comparison subjects, but the opposite pattern in the patients (F=4.56, df=1, 99, p<0.03;

Figure 2, third panel from the left). Simple effects tests indicated that schizophrenia patients had significantly lower weighted area relative glucose metabolism in the left mediodorsal nucleus, compared with the healthy subjects (F=13.28, df=1, 99, p<0.0001), but not in the right mediodorsal nucleus (p>0.05).

Pulvinar

The group-by-hemisphere ANOVA for weighted area relative glucose metabolism in the pulvinar failed to show a main effect for group or an interaction with group.

Centromedian nucleus

Patients had significantly less metabolism in the centromedian nucleus, compared with the healthy subjects, as indicated by a main effect for group (patients: mean=17.36, SD=4.45; comparison subjects: mean=19.76, SD=5.59) (F=6.87, df=1, 99, p<0.02). The group-by-hemisphere interaction was not significant.

Relative Glucose Metabolism in the Whole Thalamus

No significant differences in relative glucose metabolism in the whole thalamus were found between the patients and the comparison subjects (patients: mean=1.11, SD=0.10; comparison subjects: mean=1.08, SD=0.09; p=0.13); group and higher-order interactions with group were not significant.

To determine whether relative glucose metabolism was reduced in schizophrenia in the portions of the thalamus excluding the key nuclei (mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, and centromedian nucleus), we conducted a group (healthy subjects, schizophrenia patients)-by-hemisphere (left, right) mixed-design ANOVA. For each hemisphere, the dependent variable was the cross-product of the relative volume of whole thalamus multiplied by the average relative glucose metabolism in whole thalamus (multiplied by 10,000) minus the cross-products of the relative volume and the relative glucose metabolism within each of the three regions of interest (mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, and centromedian nucleus) multiplied by 10,000. Neither the main effect of group (p=0.23) nor the group-by-hemisphere interaction was significant (p=0.74) (left hemisphere in the patients: mean=96.33, SD=15.51; left hemisphere in the comparison subjects: mean=93.18, SD=31.94; right hemisphere in the patients: mean=102.75, SD=13.93; right hemisphere in the comparison subjects: mean=97.73, SD=15.83)

Effect Sizes

The effect sizes

(45) for the differences between the healthy comparison subjects and the schizophrenia patients shown in

Figure 2 were in the medium range for center-of-mass relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal nucleus (effect size=0.45) and in the centromedian nucleus (effect size=0.50) and in the small range for center-of-mass relative glucose metabolism in the pulvinar (effect size=0.28). The effect sizes for average relative glucose metabolism in the within-edge region of interest were in the medium range for the pulvinar (effect size=0.50) and in the small range for the mediodorsal nucleus (effect size=0.21) and the centromedian nucleus (effect size=0.28). The effect sizes for weighted area relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal nucleus for each hemisphere were in the medium range for the left hemisphere (effect size=0.76) and in the small range for the right hemisphere (effect size=0.27). The effect sizes for center-of-mass relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal nucleus for each hemisphere were in the medium range for the left hemisphere (effect size=0.73) and in the small range for the right hemisphere (effect size=0.27).

Serial Verbal Learning Task Performance and Thalamic Function

The patients recalled significantly fewer correct words, compared with the healthy comparison subjects (patients: mean=7.94, SD=3.71; comparison subjects: mean=12.89, SD=1.96) (t=8.62, df=96, p<0.00001). The patients had lower semantic clustering strategy scores than the comparison subjects (patients: mean=3.08, SD=2.80; comparison subjects: mean=7.55, SD=2.83) (t=7.65, df=96, p<0.00001), more perseveration than the comparison subjects (patients: mean=1.03, SD=1.63; comparison subjects: mean=0.55, SD=0.69) (t=–2.03, df=96, p<0.05), and more intrusion errors than the comparison subjects (patients: mean=0.35, SD=0.62; comparison subjects: mean=0.08, SD=0.16) (t=–3.18, df=96, p≤0.002). The two groups did not differ on use of the serial ordering strategy (patients: mean=0.52, SD=0.40; comparison subjects: mean=0.72, SD=1.25) (p=0.35).

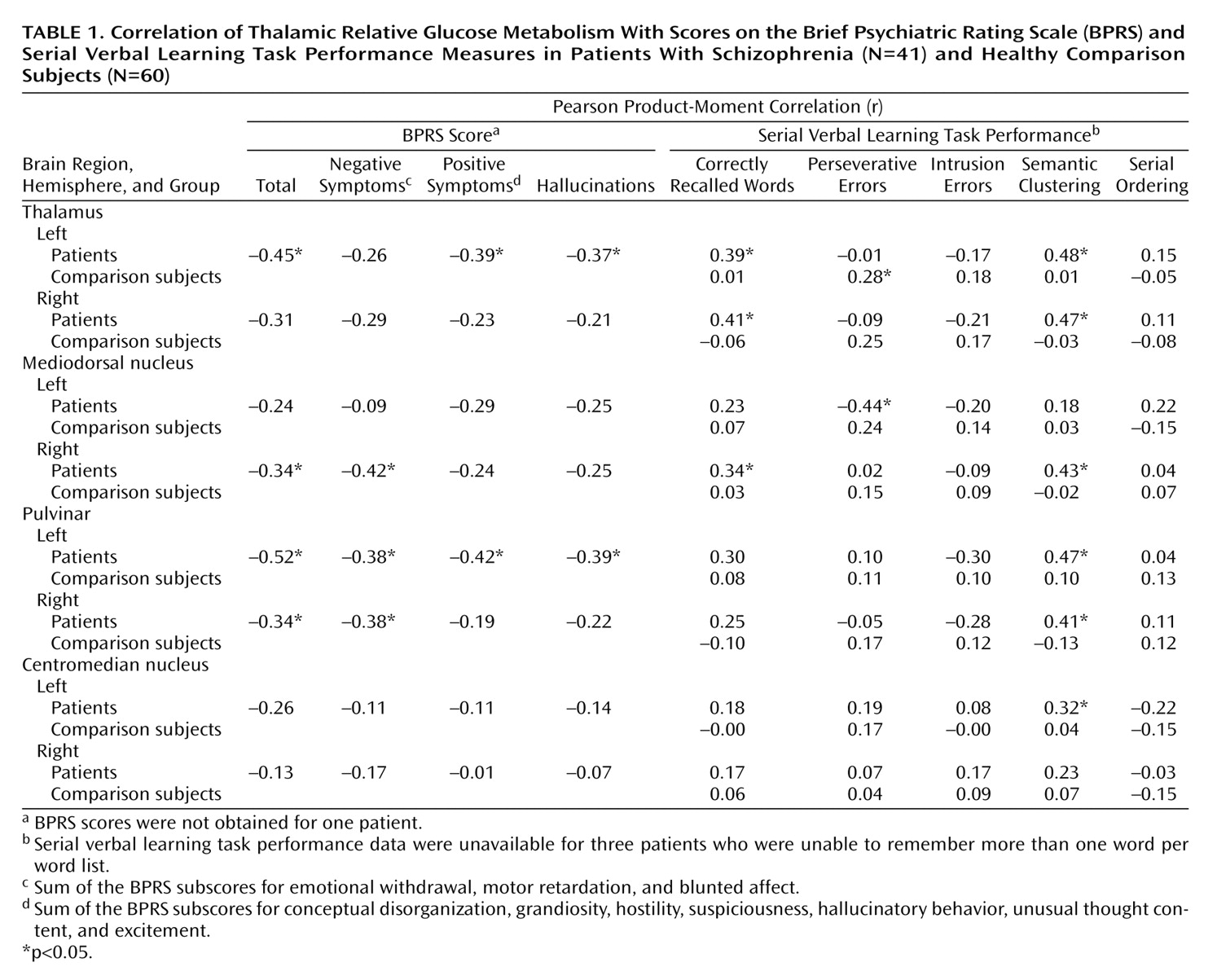

Among the comparison subjects, no significant positive correlation between good performance and relative glucose metabolism in the thalamus or thalamic nuclei was observed. In contrast, in the patient group, greater average relative glucose metabolism both in the whole thalamus and the mediodorsal nucleus was associated with greater recall (

Table 1). Better use of semantic clustering was associated with greater relative glucose metabolism in the whole thalamus, mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, and centromedian nucleus. Greater average relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal nucleus was associated with fewer perseverative errors.

Clinical Symptoms and Thalamic Function

The patients’ mean score for the 18-item BPRS on the day of the PET scan was 52.4 (SD=12.7, range=25–89). The mean value for the negative symptom composite score was 9.4 (SD=2.8, range=4–14), and the mean for the positive symptom composite score was 22.0 (SD=7.9, range=9–46).

Greater average relative glucose metabolism in the whole thalamus, mediodorsal nucleus, and pulvinar was generally associated with fewer clinical symptoms, including hallucinations, as indexed by the BPRS (

Table 1).

Thalamic Function and Age

Among the comparison subjects, relative glucose metabolism in the left (r=0.40, df=58, p<0.01) and right whole thalamus (r=0.35, df=58, p<0.01) increased with age. Average relative glucose metabolism in the right pulvinar (r=0.29, df=58, p<0.03) and left and right centromedian nucleus also increased with age (r=0.36, df=58, p<0.01, and r=0.29, df=58, p<0.03, respectively). The correlation for the left pulvinar and age only approached significance (r=0.24, df=58, p=0.07). Age was not correlated with relative glucose metabolism in the left and right mediodorsal nucleus (r=0.16, df=58, p=0.21, and r=0.02, df=58, p=0.87, respectively).

The patients showed the same correlational pattern as the healthy volunteers, with greater average relative glucose metabolism in the left and right total thalamus increasing with age (r=0.35, df=39, p<0.03, and r=0.33, df=39, p<0.04, respectively). Relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, and centromedian nucleus was not associated with age in the patient group (all r≤0.17, df=39, p≥0.29).

Discriminant Analysis

All 12 variables (mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, and centromedian nucleus volume and relative glucose metabolism values for each hemisphere) were first included in the discriminant analysis model, and at each step, the variable that contributed the least to the prediction of group membership was removed. This analysis classified 88.3% of the healthy comparison subjects (53 of 60) and 46.3% of the schizophrenia patients (19 of 41) correctly, resulting in correct classification of a total of 71.3% of the subjects. This discriminant analysis was based on only two of the 12 possible variables—relative glucose metabolism in the left mediodorsal nucleus and relative glucose metabolism in the right pulvinar. The F to remove was 12.9 for the left mediodorsal nucleus (p≤0.001) and 16.7 for the pulvinar (p≤0.0001). The F value associated with this discriminant function was F=10.5 (df=2, 980, p<0.0001).

Discussion

Metabolic Rate and Nuclear Volume

We found significantly lower relative metabolic rates in patients with schizophrenia than in healthy subjects in the mediodorsal nucleus, which is primarily associated with the prefrontal cortex, and in the centromedian nucleus, which is primarily associated with the striatum but also projects to the prefrontal cortex. Although we had previously found smaller volumes of the pulvinar in patients with schizophrenia

(20,

21), lower relative metabolic rates in this region were not seen in the patients in the present study. This finding was true for the center-of-mass analysis, which minimizes partial volume effects at the cost of having center-weighted assessment; the traced area analysis, which weights all pixels in the MRI-based thalamic outline equally; and the traced area-by-relative rate, which would be nonsignificant if the metabolic rate were slightly higher per unit area. The data shown in

Figure 2 suggest that some metabolic compensation for lower volume may be taking place in the pulvinar in patients with schizophrenia. The negative correlation between activity in the pulvinar and positive symptoms suggests that this increased activity may be a compensatory mechanism that functions to control positive symptoms. Observation of longitudinal course and the effects of medication will be valuable in evaluating this speculation.

Specificity of Findings to Mediodorsal Nucleus, Pulvinar, and Centromedian Nucleus

We detected no differences in metabolic rate between patients and comparison subjects in the whole thalamus or the whole thalamus excluding the three nuclei (mediodorsal nucleus, pulvinar, and centromedian nucleus), indicating that the findings have a degree of nuclear specificity. These changes are consistent with a deficit in the frontostriatothalamic circuitry of patients with schizophrenia, which was suggested in our earlier findings of diminished correlations between metabolic rate in the frontal lobe and thalamus

(46) and lower metabolic rates in the region of the mediodorsal nucleus

(29,

30) and the striatum

(44).

Imaging Limitations

Interpretation of these data is limited by the accuracy of our spatial assessment of the nuclei of the thalamus. The volume of the mediodorsal nucleus (400–600 mm

3) is relatively large, compared with the PET resolution of 4.5 mm full-width at half-maximum in-plane or about 125 mm

3 in three dimensions. We have demonstrated the reliability of our mediodorsal nucleus tracings

(21,

41), and others have noted the distinctive appearance of the mediodorsal nucleus on MRI images

(47). However, the alignment of the PET and MRI images is critical and may have an error in the range of 1–2 mm. The mediodorsal nucleus was traced on the coregistered MRI, and PET pixels were identified with respect to the thalamic outline. Thus, errors due to variation in the position of the thalamus within the entire brain outline, as may occur in whole-slice statistical probability mapping, do not contribute to potential error in our study. While the PET images may not be perfectly registered, we have no indication that coregistration errors are systematically different in patients and in healthy comparison subjects. Greater motion in patients with schizophrenia during image acquisition might produce lower-resolution images with greater variation in registration error, but this effect is unlikely to yield lower metabolic rates in the patient group. An enlarged third ventricle, especially if combined with head movement in the y direction, might lower mediodorsal nucleus metabolic rates; however, our assessment of head motion during fMRI procedures suggests that head flexion is more common and an actual shift of the head laterally (moving the third ventricle into the region of the mediodorsal nucleus) is uncommon. It is noteworthy that the metabolic values in the pulvinar, which is adjacent to the larger ventricular atrium, did not show lower metabolic rates, diminishing the likelihood that this artifact occurred. Last, we obtained only activation FDG values, rather than examining a comparison of activation with rest or a control task. Although [

15O]H

2O PET affords the capability of acquiring two scans on the same day (e.g., rest and task), the PET scanner’s 4.5-mm resolution with FDG as tracer would be diminished substantially. Previous fMRI activation studies in healthy subjects and patients with schizophrenia have shown between-group differences in activation in nearly the geometric center of the mediodorsal nucleus (coordinates x=3, y=–17, z=5) during an auditory oddball task

(48) and in the mediodorsal nucleus with a center reported near the posterior lateral edge of the mediodorsal nucleus at coordinates x=–10, y=–22, z=8

(49).

Age and Diagnostic Specificity

Relative metabolic rates in the thalamus increased with age, as in another recent study

(50). Another study showed that bipolar disorder patients do not have smaller whole thalamus size

(51), but detailed measurement of the mediodorsal nucleus and pulvinar are necessary to demonstrate diagnostic specificity for schizophrenia. Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, who show hyperfrontal function that has been considered the opposite of the pattern found in schizophrenia, also show increased thalamic activity in single photon emission computed tomography scans

(52), as do patients with anorexia nervosa

(53). These findings suggest that lower thalamic function is not common to all psychiatric disorders.

Striatum-Thalamus Interactions and Centromedian Nucleus

Deficits in the frontostriatothalamic circuits in schizophrenia have been proposed and reviewed

(54–

56). FDG PET studies have confirmed lower metabolic rates in all three areas

(57), and studies of

N-acetyl-

d-aspartic acid concentrations have demonstrated lower metabolic rates in frontal and striatal areas

(58). Since the centromedian nucleus sends an excitatory projection to the striatum

(18), diminished centromedian nucleus activity would be consistent with the lower levels of striatal and cortical activation seen in patients with schizophrenia, compared to healthy subjects.

Pulvinar, Laterality, and Schizotypal Disorder

In a previous study

(41) that included subjects with schizotypal personality disorder, we found smaller volumes of the mediodorsal nucleus to be specific to schizophrenia, while smaller volumes of the pulvinar were seen both in patients with schizophrenia and in those with schizotypal personality disorder. On the basis of that observation and the widespread connections of the pulvinar with the temporal association and sensory cortex

(4), we previously suggested that the pulvinar abnormalities might be linked to the associational and perceptual disturbances common to both schizophrenia and schizotypal personality disorder

(30). The negative correlation between pulvinar activity and hallucinatory experience observed in the present study is consistent with that interpretation. It is noteworthy that this correlation is strongest for the left pulvinar, since the pulvinar is connected with asymmetrical areas of the superior temporal and inferior parietal lobes

(59). Left temporal deficits are important in schizophrenia

(60–

62). Left temporal volume deficits have been reported

(63) and observed in some of the patients in the present study

(64). No group-by-hemisphere interaction was significant for the pulvinar, whereas the group-by-hemisphere interaction was significant for the mediodorsal nucleus, confirming a greater left-sided metabolic deficit in schizophrenia. Last, it should be noted that post hoc t tests indicated relative metabolic rates for the within-edge region of interest that were higher in the patients with schizophrenia than in the healthy comparison subjects, consistent with exploratory rCBF studies

(37,

38).

Medial Dorsal Nucleus

Given the connection of the mediodorsal nucleus with the prefrontal cortex, our finding of lower relative glucose metabolism in the mediodorsal nucleus in the patients with schizophrenia is consistent with the cognitive dysmetria theory of schizophrenia

(65). This model implicates connectivity among nodes located in the prefrontal region, the thalamic nuclei, and the cerebellum. A disruption in this circuitry produces difficulty in prioritizing, processing, coordinating, and responding to information. Among the patients in our study, greater mediodorsal nucleus dysfunction was associated with less use of semantic clustering, poorer verbal memory performance, and more severe negative symptoms. Thus, our mediodorsal nucleus finding is consistent with the “poor mental coordination” aspect of cognitive dysmetria, as well as with the attentional and memory deficits widely observed in schizophrenia.