Bipolar disorder is a recurrent, severe, and often debilitating illness characterized by episodes of mania and depression and long-term psychosocial disability

(1,

2). It affects an estimated 3.7% of the adult population

(3). For many years, the standard treatments for acute mania in the United States have been lithium and divalproex, administered either alone or in combination with an antipsychotic medication

(4). More recently, the atypical antipsychotic olanzapine was approved in the United States and Europe for use, as monotherapy, in the treatment of acute mania

(5,

6). Despite these advances, treatment limitations remain in terms of modest efficacy, delayed onset of action, undesirable side effects, and the need to monitor serum levels for some of these treatments.

Several lines of evidence suggest that risperidone has an important role in the treatment of acute mania. Risperidone’s unique receptor binding profile—distinguished by potent antagonism of the serotonin 5-HT

2A, dopamine D

2, and alpha-adrenergic

2c receptors

(7,

8)—has been hypothesized to be relevant for the treatment of affective disorders

(9). In a previous randomized, placebo-controlled trial, Sachs and colleagues

(10) reported that the combination of risperidone and lithium or valproate was more efficacious than a mood stabilizer alone in the treatment of acute bipolar mania. Additionally, in a small pilot study, risperidone monotherapy was shown to be comparable to lithium and haloperidol in the treatment of acute mania

(11).

Based on risperidone’s pharmacological profile and these initial studies, a large randomized controlled trial was conducted to evaluate risperidone monotherapy in the treatment of acute mania.

Method

Design

This was a 3-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, multicenter trial to assess the efficacy and tolerability of risperidone monotherapy in the treatment of acute mania.

Subjects

Eligible participants were men and women age 18 years or older who met DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder, current episode pure mania (296.4x). Patients must have had a history of at least one prior documented manic or mixed episode that required treatment prior to screening. The patients were voluntarily hospitalized for treatment at the time of enrollment and had a Young Mania Rating Scale total score ≥20 at the screening and baseline evaluations and a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale total score ≤20 at the baseline evaluation.

Patients were excluded from the study if their baseline Young Mania Rating Scale total score was ≥25% lower than the screening score. Patients were also excluded if they had a diagnosis of a mixed episode, schizoaffective disorder, borderline or antisocial personality disorder, seizure disorder, a history of substance dependence within 3 months of the screening, or were considered to be at significant risk for suicidal or violent behavior during the course of the trial. Additional exclusion criteria were a history of poor response to monotherapy with an antimanic agent or antipsychotic drug; receipt of clozapine, electroconvulsive therapy, or antidepressant therapy within 4 weeks before the screening evaluation; or participation in any investigational drug trial in the 3 months before the screening examination. Subjects who received clozapine, electroconvulsive therapy, or antidepressant therapy in the 4 weeks preceding the screening examination were also excluded, since the potential long-term effects of these treatments on safety and efficacy parameters might present a confounding factor in the interpretation of the study results. Women of childbearing potential were excluded unless they were 1 year postmenopausal, surgically sterile, or effectively practicing an acceptable method of contraception. Patients were also excluded from the study if they had a history of hypersensitivity or allergy to risperidone or had severe similar reactions to other drugs. After receiving a complete description of the study, patients or their legal representatives provided written, informed consent to participate. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review or human subjects board of each study site.

Procedure

At screening, all patients who had been receiving any psychotropic medications (other than benzodiazepines to control for agitation, irritability, restlessness, insomnia, and hostility) entered a washout period for up to 3 days. In addition, patients who had ingested substances of abuse or who had been intoxicated with alcohol within 3 days prior to baseline also entered a washout period for up to 3 days. The actual duration of the washout period for any given patient was such that at the baseline visit, the patient would not have received any of these substances for at least 3 days. The following medications were prohibited within 3 days (at a minimum) before the baseline visit and during the trial: anticonvulsant drugs, antidepressant drugs/St. John’s wort (prohibited within 4 weeks of screening), antimanic drugs, antipsychotics/neuroleptics other than trial medication, cognition enhancers, dopamine-releasing or dopamine agonist drugs, lithium, sedatives/hypnotics/anxiolytics (other than lorazepam), and other drugs or herbal preparations used by the patient for a psychotropic effect (e.g., Ginkgo Biloba, kava kava). Lorazepam was permitted for the control of agitation, irritability, restlessness, insomnia, and hostility up to a maximum dose of 8 mg/day during the washout period and the first 3 days of the treatment period, 6 mg/day during days 4–7, and 4 mg/day during days 8–10. Lorazepam was not permitted anytime thereafter or during the 8-hour period preceding a behavioral assessment. Antiparkinsonian medications were also allowed throughout the study.

Patients were randomly assigned via an interactive voice response system to receive either risperidone or placebo under double-blind conditions for 3 weeks. A dynamic method

(12) was used to randomly assign patients to treatment groups. Stratification factors were treatment center and presence or absence of psychotic features at baseline. Patients assigned to risperidone treatment received a single 3-mg dose of the study drug on day 1. The daily dose could be adjusted to 2–4 mg on day 2, to 1–5 mg on day 3, and to 1–6 mg on day 4 and thereafter at the discretion of the investigator. Adjustments to the daily dose could be by no more than 1 mg/day. All study medication was taken in the evening.

Once enrolled, patients remained hospitalized for a minimum of 7 days, after which they could be discharged and followed up as outpatients if they were considered by the investigator to be at no significant risk for suicidal or violent behavior and had a Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity scale rating ≤3.

Assessments

During the screening evaluation, all patients were administered selected modules of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID)

(13) and underwent general psychiatric evaluation, physical examination, assessment of their concomitant medication use, and an evaluation of their medical history, vital signs, and laboratory test results, including urinalysis and tests of thyroid function and pregnancy.

Efficacy

Efficacy was assessed with the following rating scales: the Young Mania Rating Scale

(14), the CGI severity scale

(15), Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale

(16), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

(17), and the Global Assessment Scale (GAS)

(18). All scales were administered at screening, baseline, and on days 1, 3, 7, 14, and 21. Additional CGI severity ratings were obtained from patients being evaluated for discharge after 1 week of hospitalization. The primary measure of efficacy was the mean baseline-to-endpoint change in total score on the Young Mania Rating Scale.

Safety

Adverse events were ascertained at each study visit and on every inpatient day. Investigators asked whether any changes in health occurred since the last evaluation, with appropriate probing of positive responses. Vital signs, weight, and results of an ECG, laboratory tests, a urinalysis, and a pregnancy test (when appropriate) were assessed at baseline. Movement disorders were evaluated at baseline and on days 7, 14, and 21 by using the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale, which assessed the frequency and severity of parkinsonism, dyskinesia, akathisia, and dystonia

(19).

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was determined from a two-sided test with a significance level of 5%. To achieve a statistical power of 90% to detect a clinically meaningful difference of 5.8 points (SD=12.6) on the change from baseline in the primary efficacy variable (total Young Mania Rating Scale score), at least 101 patients would be needed. As the anticipated percentage of randomized patients without a postbaseline Young Mania Rating Scale assessment was 20%, a minimum of 254 patients (127 per treatment group) would have had to be randomized to achieve 101 patients per group with postbaseline Young Mania Rating Scale data. Summary statistics on the baseline demographic characteristics were calculated: means and standard deviations for the continuous variables (age and body weight), numbers and percentages for the categories (sex, race, and presence/absence of psychotic features).

The last postbaseline assessments for the Young Mania Rating Scale, CGI, Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, and GAS for patients who did not complete the 3-week treatment period were carried forward to treatment endpoint. To analyze the baseline-to-endpoint change in Young Mania Rating Scale scores, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model was used, in which the treatment, treatment center, and evidence or absence of psychosis at baseline were the factors and the baseline Young Mania Rating Scale score was the covariate. The primary comparison between the risperidone and placebo groups was based on mean changes after adjusting for covariates in the ANCOVA model. The methods used to analyze secondary measures, including the CGI severity rating and scores on the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, and GAS were similar to that used in the analysis of the Young Mania Rating Scale scores. The same ANCOVA model was applied to analyses for each subgroup with the exception of the analysis by presence or absence of psychotic features, for which only treatment, treatment center, and baseline value were included in the models.

A clinical response was defined a priori as a ≥50% reduction in Young Mania Rating Scale total score from baseline at any time during the treatment period. In post hoc analyses, rates of remission at endpoint (last observation carried forward) were explored using two sets of criteria: 1) Young Mania Rating Scale ≤12 and 2) Young Mania Rating Scale ≤8 plus Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale ≤12. Clinical response rate and remission rates were analyzed by using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test for general association that controlled for the treatment center and the presence or absence of psychotic features at baseline.

Centers with less than 12 patients were pooled in a pairwise fashion according to a prespecified pooling algorithm whereby the smallest of the eligible centers was pooled with the largest, the next smallest with the next largest, etc., until each center with <12 patients was combined with another. Eight individual centers had >12 patients and were not pooled. Twenty centers were combined to make 10 pooled centers ranging in size from 11 to 14 patients. As a result, the treatment center factor in analysis models had 18 levels.

To evaluate the safety of treatment, all adverse events reported were recorded, and ECG and vital sign data were compared against prospectively defined criteria for normal results. Between-group comparisons of change from baseline in Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale and subscale scores were made by using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel mean scores test using modified ridit scores

(20) that controlled for the treatment center and the presence or absence of psychotic features at baseline.

Results

Of the 337 patients who were screened, 262 entered the randomization phase. Two hundred fifty-nine received at least one dose of study medication (134 in the risperidone group, 125 in the placebo group).

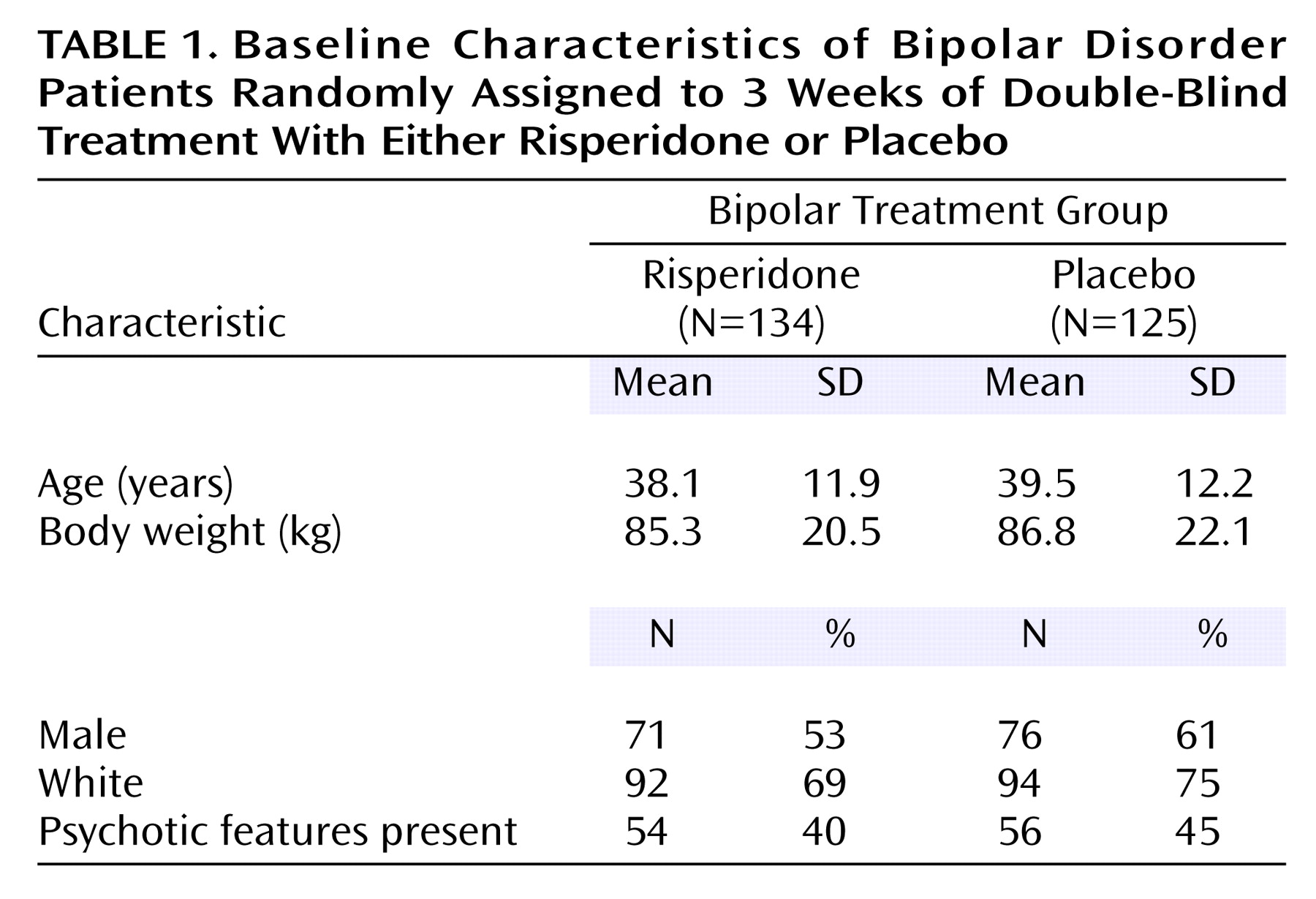

The baseline and background characteristics of the two treatment groups were similar (

Table 1). The total sample had a mean age of 39, was fairly equally split between the sexes, and was predominantly white. The mean baseline Young Mania Rating Scale total score was 29.1 in the risperidone group and 29.2 in the placebo group. At baseline, psychotic features were noted in 40% of the risperidone group and 45% of the placebo group.

There were no statistical differences between the treatment groups in the use of medications for the treatment of bipolar disorder prior to trial. During the 30-day period prior to enrollment, 74.4% of patients in the placebo group (N=93), and 71.6% of patients in the risperidone group (N=96) were receiving some medication for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Both treatment groups had a similar medication history during the 30-day period before enrollment. In both treatment groups the prior use of pharmacological treatment for bipolar disorder was similar: 72% for the risperidone group and 74% for the placebo group. The most commonly received medications for bipolar disorder treatment during the 30 days before study entry were valproate (29%), lorazepam (26.6%), olanzapine (18.5%), risperidone (17.4%), lithium (12.4%), and quetiapine (11.2%).

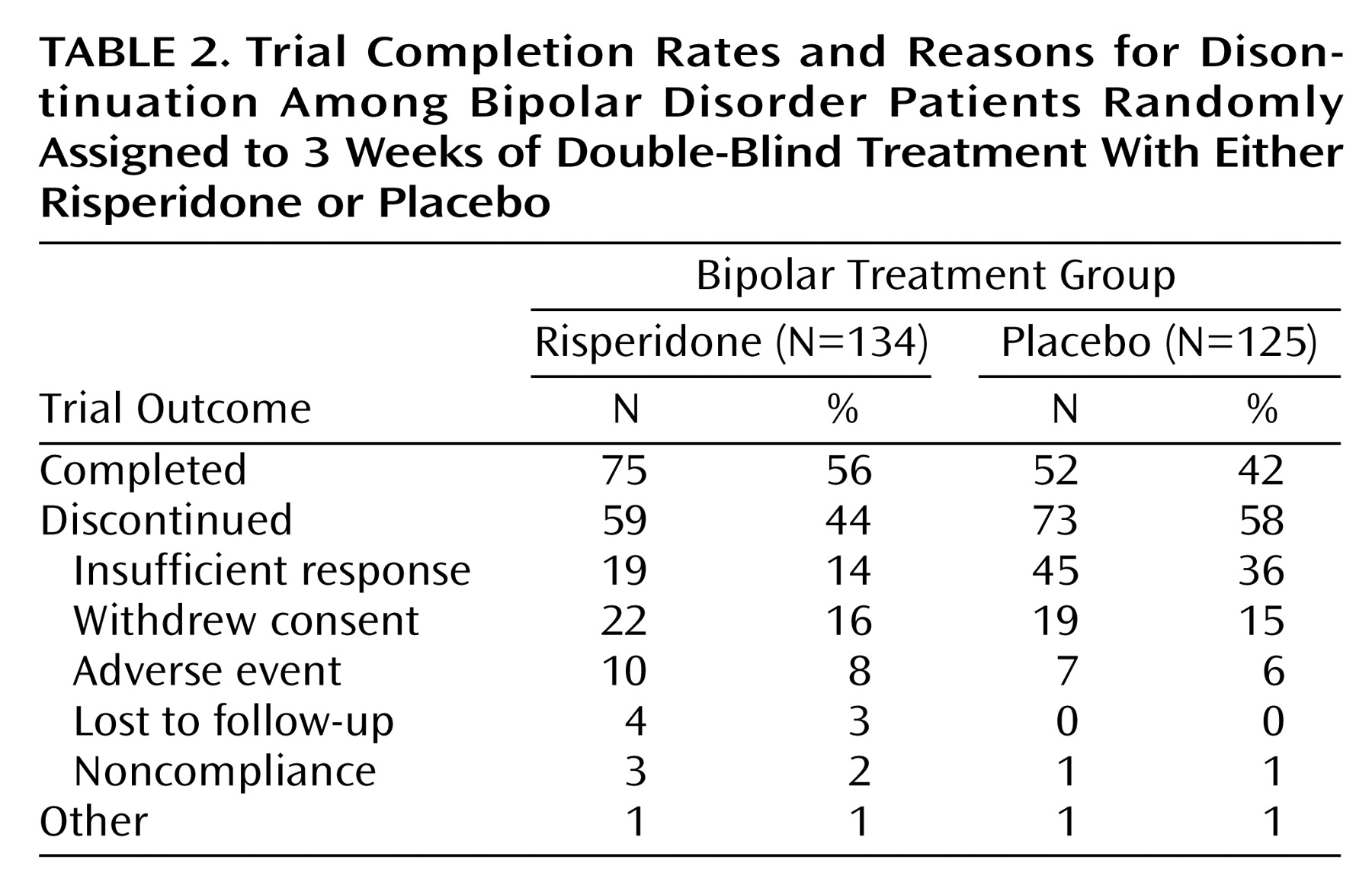

A total of 127 patients completed the study, 75 (56%) in the risperidone group and 52 (42%) in the placebo group (

Table 2). The most commonly reported reason for discontinuation from the study was insufficient response. This occurred in 36% of the placebo patients and 14% of the risperidone patients (χ

2=16.26, df=1, p<0.001).

The mean modal dose of risperidone was 4.1 mg/day (SD=1.4). The mean modal number of placebo tablets was 5.0 (SD=1.2). The median duration of treatment was 14 days (range=2–25) for placebo and 20.0 (range=1–26) for risperidone treatment. Thirty-eight percent of the patients assigned to risperidone took 5–6 mg at day 4, and this percentage only slightly increased thereafter to a maximum of 51%. The dose escalation was more important with placebo, where on day 4 already 68% of the patients were taking the maximum number of tablets.

During the treatment period, 81% of the risperidone group and 82% of the placebo group received concomitant lorazepam and 22% and 11%, respectively, received antiparkinsonian medications, most commonly benztropine mesylate.

Efficacy

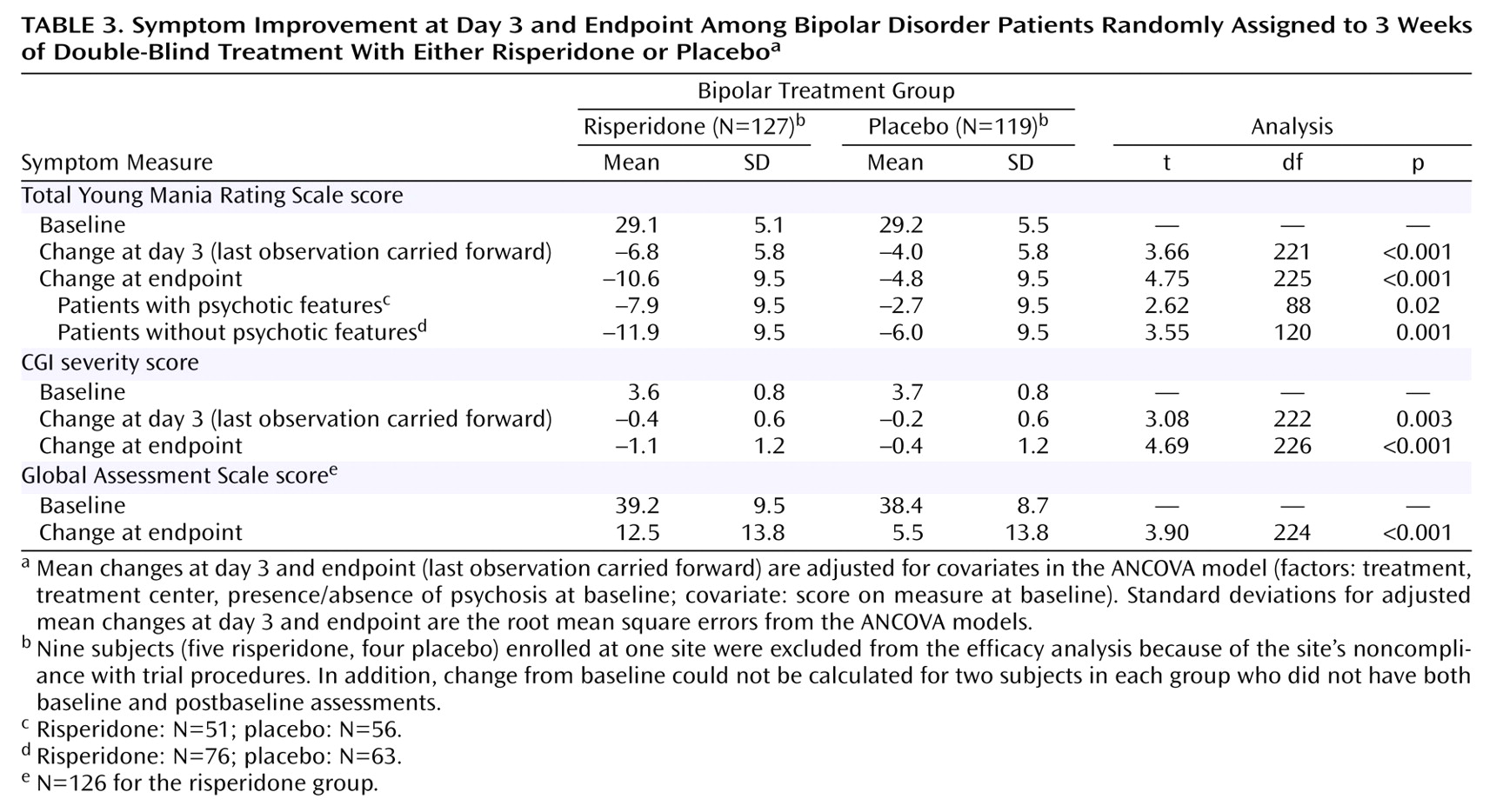

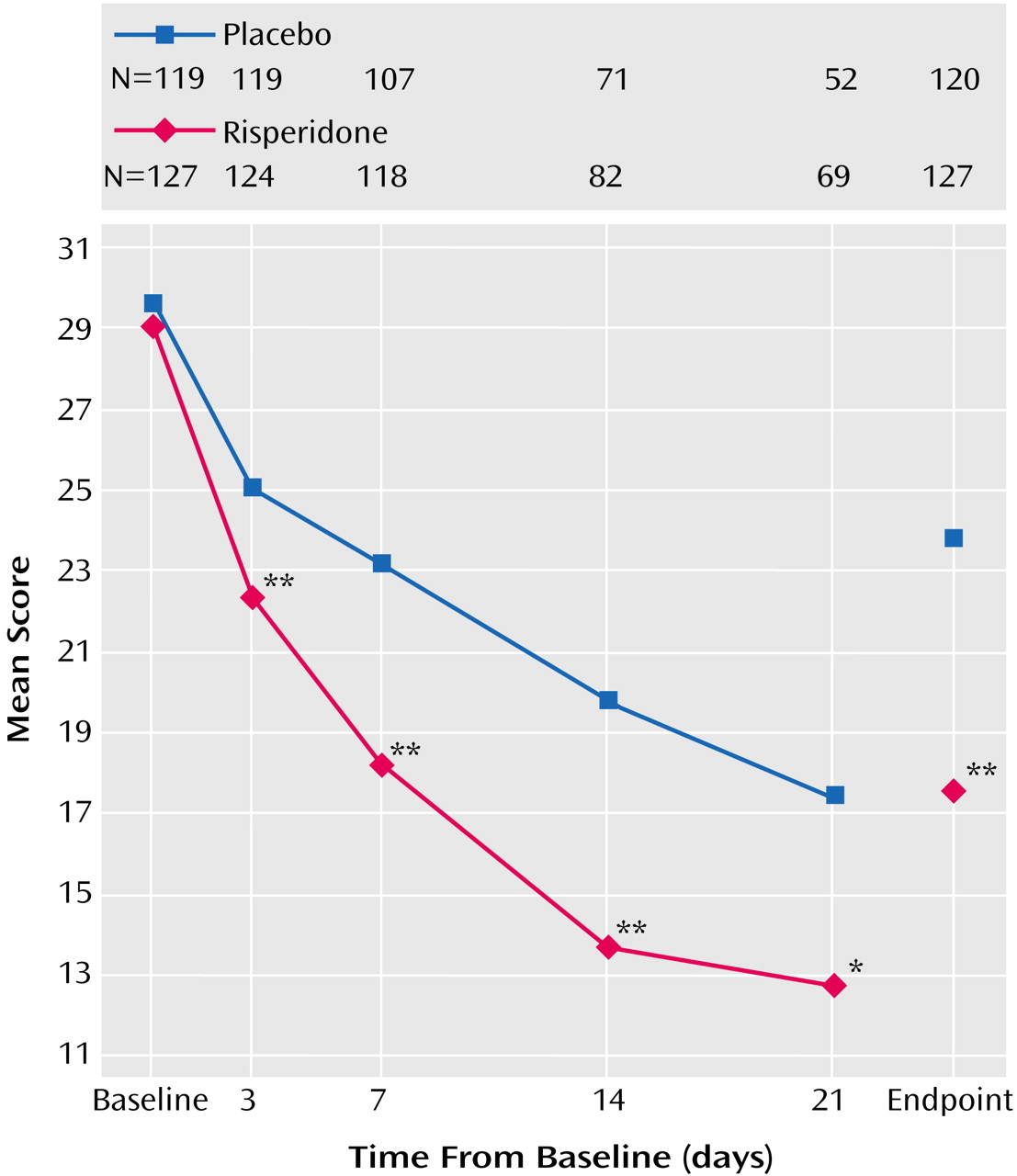

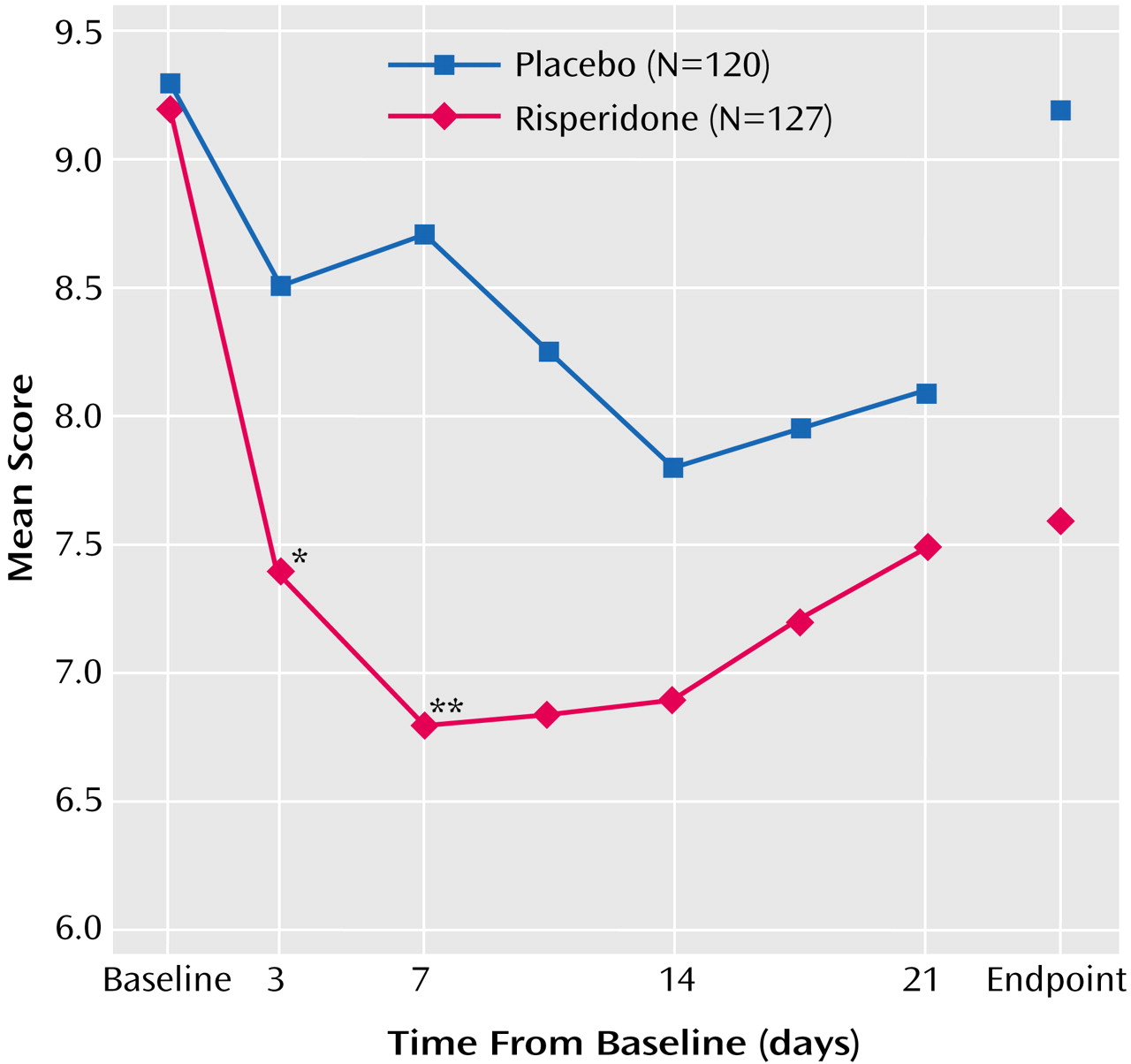

Nine subjects (five risperidone, four placebo) enrolled at one site were excluded from the efficacy analysis because of the site’s noncompliance with trial procedures. In addition, change from baseline could not be calculated for two subjects in each group who did not have both baseline and postbaseline assessments. Therefore, the analysis of change from baseline for Young Mania Rating Scale data included 127 subjects in the risperidone group and 119 in the placebo group. The mean baseline Young Mania Rating Scale total score was 29.1 in the risperidone group and 29.2 in the placebo group. Young Mania Rating Scale score reductions were significantly greater in the risperidone group than in the placebo group beginning at day 3 and at every subsequent evaluation (

Figure 1 and

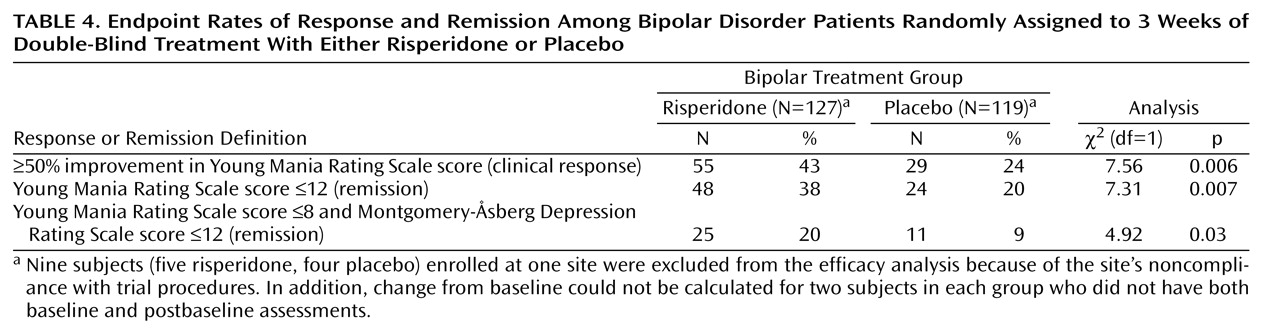

Table 3). At endpoint, subjects treated with risperidone had a mean reduction (adjusted for covariates in the ANCOVA model) of 10.6 points on the Young Mania Rating Scale compared with a mean reduction of 4.8 points in the placebo subjects. At endpoint, significantly more subjects treated with risperidone (43%) compared with placebo-treated subjects (24%) demonstrated a therapeutic response (Young Mania Rating Scale score ≥50% lower than at baseline).

A post hoc analysis of remission rates, utilizing the criterion of a Young Mania Rating Scale score ≤12 at endpoint, found 38% of risperidone patients versus 20% of placebo patients attained remission (

Table 4). Utilizing the more stringent criteria of a Young Mania Rating Scale score ≤8 and a Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale score ≤12, remission rates were 20% in the risperidone group compared with 9% in the placebo group.

Patients in the risperidone group also demonstrated significantly greater improvements in measures of severity of illness based on CGI severity scores, evident at day 3 and at each time point thereafter. More patients were regarded as not ill, very mildly ill, or mildly ill at endpoint with risperidone (53.5%) compared with placebo (25.8%).

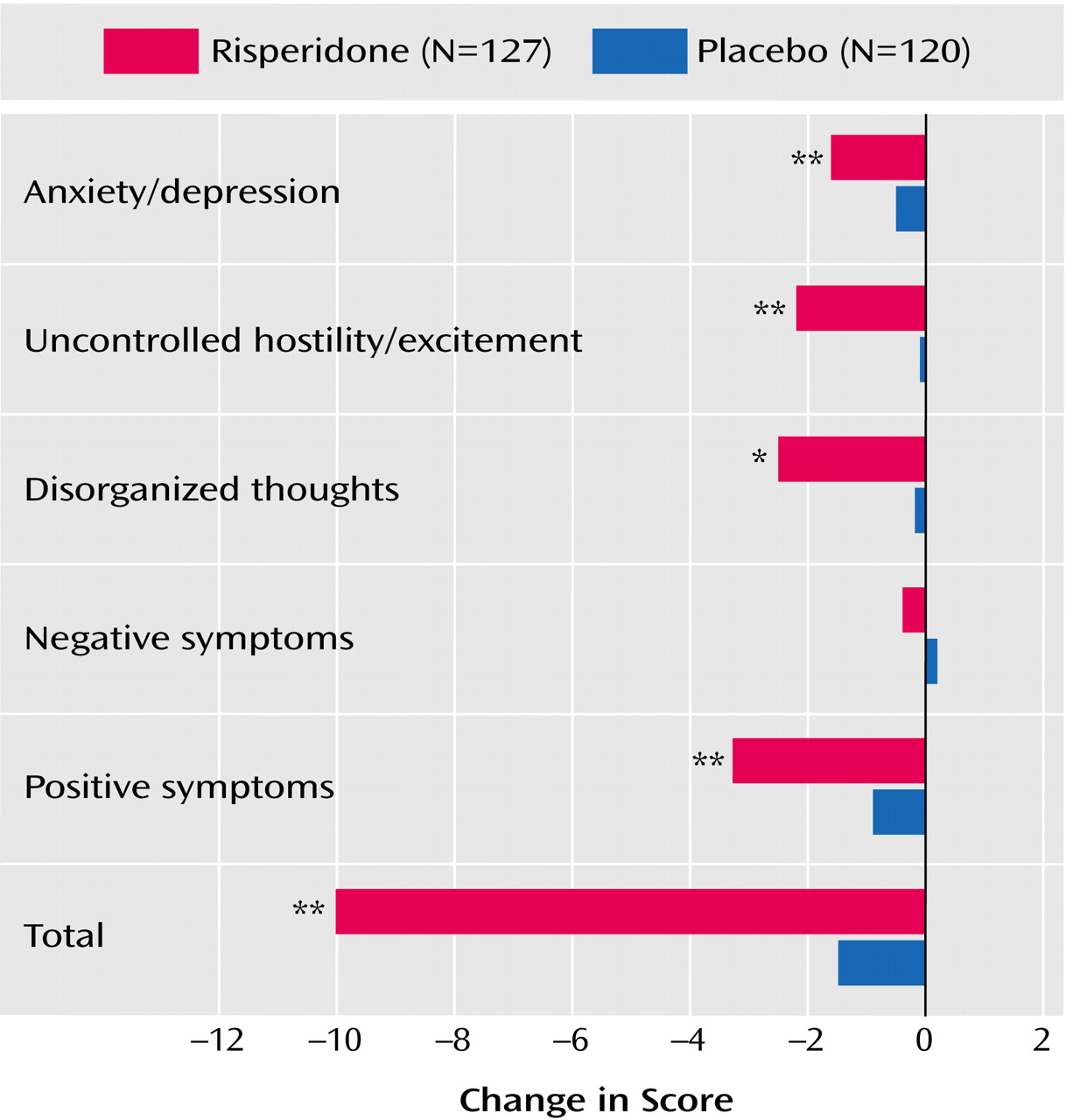

Significantly greater improvements in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale total score and scores on four of the five factors (positive symptoms, disorganized thoughts, uncontrolled hostility/excitement, and anxiety/depression) were seen in the risperidone group (

Figure 2). Mean baseline Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores were 9.2 (SD=4.9) in the risperidone group, and 9.3 (SD=4.8) in the placebo group. Scores were lower than baseline at each subsequent time point in both groups, with significantly greater changes in the risperidone group than the placebo group at day 3 and week 1 (

Figure 3). Finally, psychosocial functioning was significantly improved based on the differences in improvement in Global Assessment Scale scores at endpoint (

Table 3).

Subgroup Analysis

The effects of risperidone therapy, as determined from the Young Mania Rating Scale total score changes from baseline, were consistent across the patient subgroups defined by age, sex, race, and severity scores. Risperidone was more efficacious than placebo both in patients with and without psychotic features at baseline (

Table 3). The baseline-to-endpoint reduction in Young Mania Rating Scale total score was greater in the nonpsychotic patients than in the psychotic patients.

Safety and Tolerability

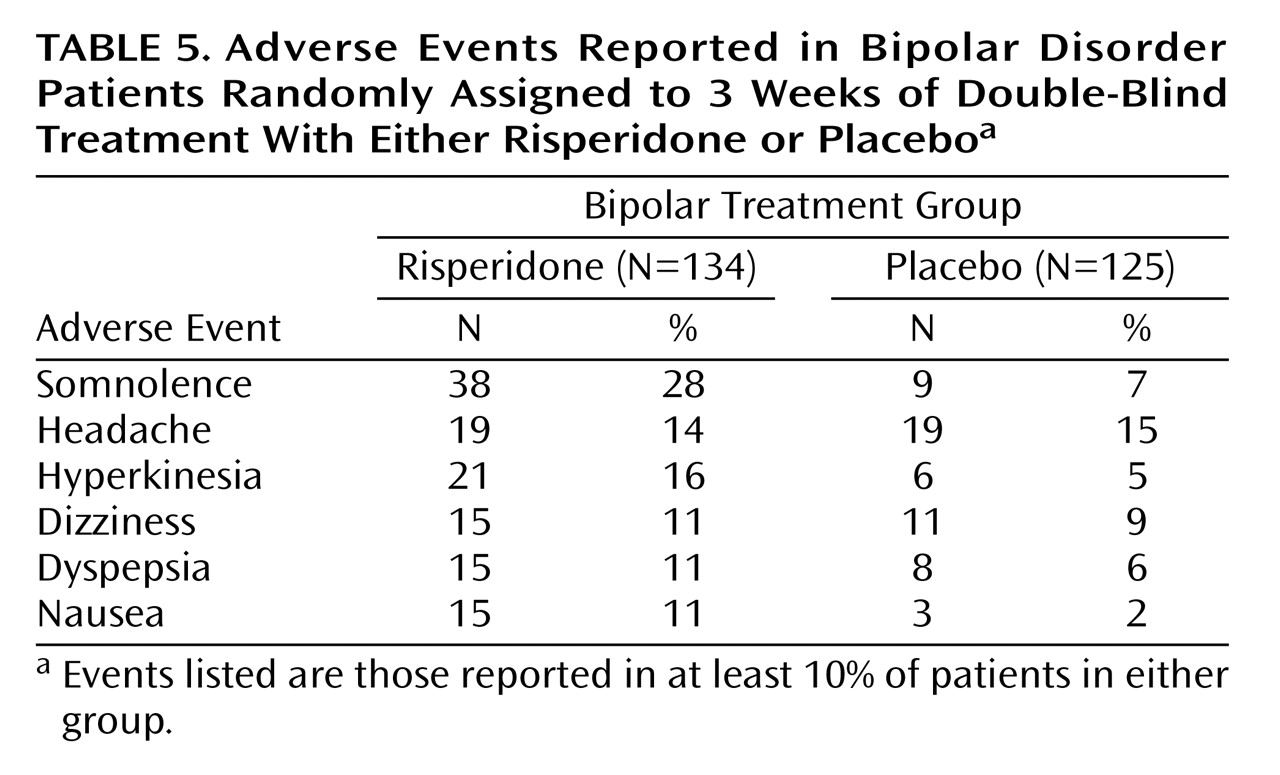

The safety analysis included all 259 patients who received at least one dose of the study medication. The rate of discontinuation due to adverse events was similar in both treatment groups (8% in the risperidone group, 6% in the placebo group). Adverse events occurring in >10% of patients included somnolence, headache, hyperkinesia, dizziness, dyspepsia, and nausea (

Table 5). Adverse events that led to treatment discontinuation were observed in seven patients in the placebo group and 10 in the risperidone group. The most common serious adverse event was manic reaction, observed in 10 (7.5%) of the risperidone and six (4.8%) of the placebo subjects, followed by agitation (reported by three subjects given risperidone and none given placebo). Two deaths (one caused by a motor vehicle accident 20 days after the patient withdrew from the study and the other by a choking accident 13 days after patient withdrawal from the study) occurred during this study, both of which were in the placebo group.

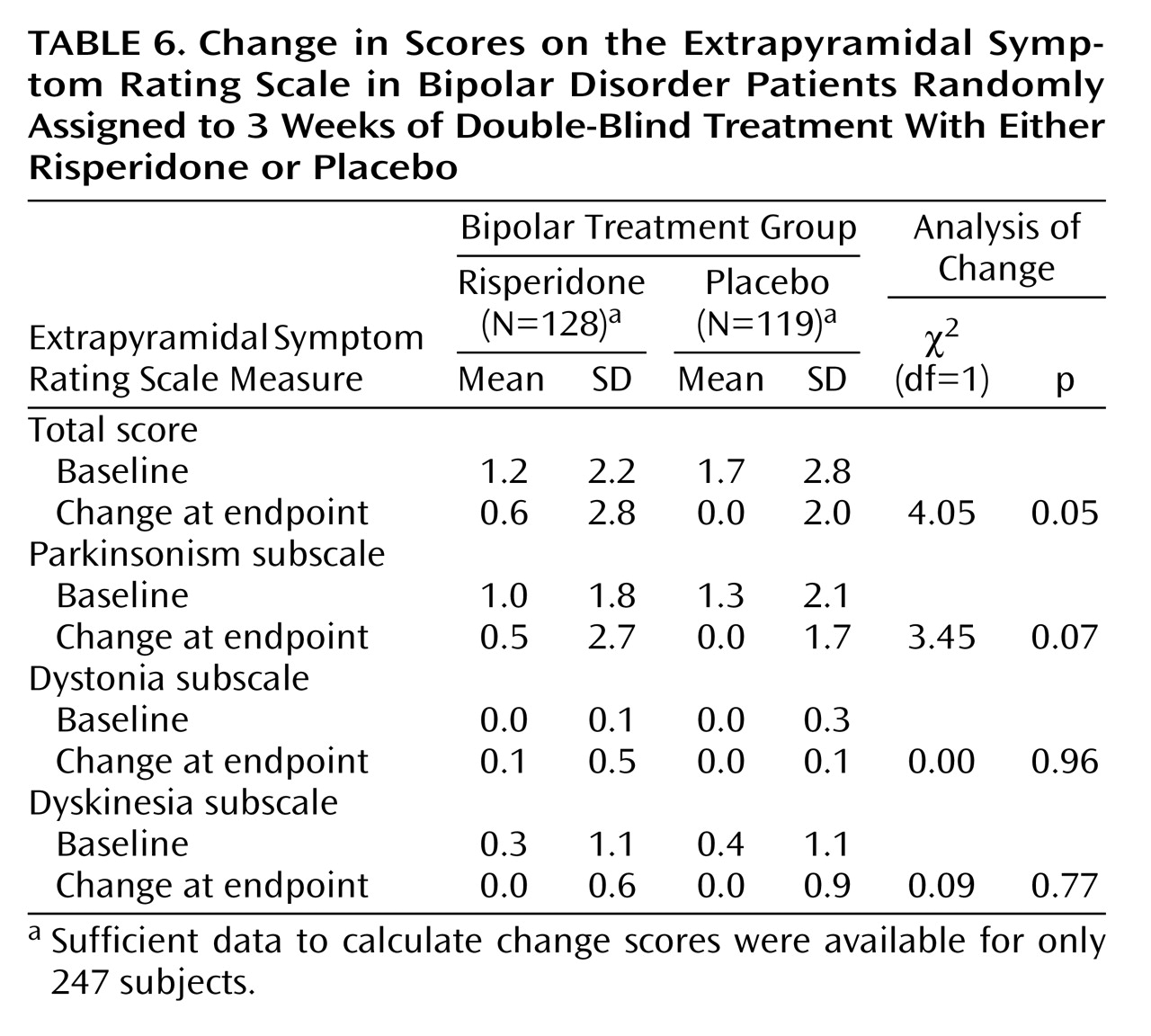

The severity of extrapyramidal symptoms, as assessed by the Extrapyramidal Symptom Rating Scale, was mild at baseline. Increases at endpoint were small in both groups but statistically significantly larger for risperidone than placebo for the total score (

Table 6). Among the three subscales (parkinsonism, dystonia, and dyskinesia), there were no significant differences at endpoint between risperidone and placebo.

No clinically meaningful differences in vital signs or ECG results were noted between the treatment groups. The QTc interval did not exceed 500 msec in any patient in either group regardless of the correction factor used in the analysis. Except for plasma prolactin concentrations, clinical laboratory (including glucose) values did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups. Among men, the mean plasma prolactin levels increased from 13.7 ng/ml (SD=9.8) to 43.5 ng/ml (SD=23.0) in the risperidone group and decreased from 14.1 ng/ml (SD=17.7) to 12.5 ng/ml (SD=8.7) in the placebo group. Among women, the mean plasma prolactin levels increased from 19.4 ng/ml (SD=26.6) to 96.1 ng/ml (SD=51.4) in the risperidone group and from 14.5 ng/ml (SD=11.8) to 14.6 ng/ml (SD=11.2) in the placebo group. Mean body weight changes were 1.6 kg (SD=2.2) in the risperidone group and –0.25 kg (SD=2.4) in the placebo group (t=6.47, df=225, p<0.001).

Discussion

The American Psychiatric Association’s recent Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients With Bipolar Disorder

(4) recommends that “the first-line” pharmacologic treatment for patients with severe mania is lithium or valproate plus an antipsychotic. A previous study had demonstrated that risperidone significantly enhances the treatment of acute mania when combined with mood stabilizers

(10). This is the first large-scale, controlled study that demonstrates that risperidone, when used alone, significantly reduces the manic symptoms associated with bipolar I disorder. Risperidone, compared with placebo, produced significantly greater improvements on the Young Mania Rating Scale and the CGI as well as all other measures of efficacy at almost every treatment evaluation. The evidence for efficacy and safety of risperidone provided by this trial increases for the physician the treatment options that are based on well-controlled data. The efficacy of risperidone was established in both patients with or without psychosis.

Significant improvement was observed 3 days after treatment initiation. This rapid onset of action increases safety by stabilizing the patient more quickly. It may also shorten the amount of time in the hospital. Significantly more patients receiving risperidone, compared with those receiving placebo, attained remission. Patients treated to remission are less likely to relapse and more likely to resume prior role functioning. That the improvement with risperidone is broad based is supported by the significant improvement in psychosocial functioning as reflected in GAS scores.

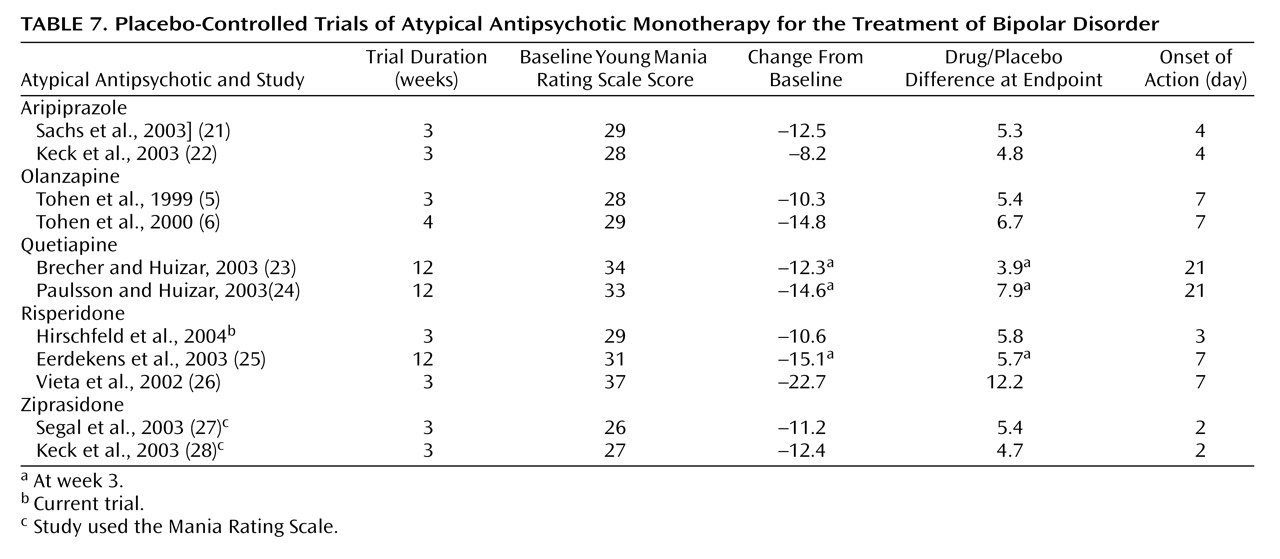

As seen in

Table 7, the magnitude of effect (drug/placebo difference at endpoint, adjusted for baseline severity) of 5.8 in this trial compares favorably to the magnitude of effect shown on the Young Mania Rating Scale in recently conducted 3- (or 4-) week monotherapy trials of acute mania with aripiprazole, olanzapine, quetiapine, two other studies of risperidone, and ziprasidone.

Adverse events were reported more often in the risperidone treatment group than in the placebo group. However, in both groups, most adverse events were rated as mild or of moderate severity. There were only four in which the frequency in the risperidone group was substantially higher. The most frequent serious adverse event in both groups was manic reaction.

There was a higher incidence of extrapyramidal symptoms in the risperidone group than in the placebo group, although most extrapyramidal side effect-related adverse events were rated as mild in both groups. The higher rate of antiparkinsonian medication in the risperidone group likely is reflective of the higher extrapyramidal side effect-related adverse event rate in that group. Among the 134 patients in the risperidone group, only one experienced a severe extrapyramidal side effect-related adverse event. Prolactin levels in both male and female subjects were increased relative to baseline in the risperidone group. This effect has been described in other short-term trials with risperidone and seems to be less pronounced in longer-term trials. However, a meta-analysis of two large, multinational studies of schizophrenia found no correlation between treatment-induced hyperprolactinemia and the emergence of prolactin-related side effects

(29). There was a statistically significant difference between treatment groups for weight change from baseline to endpoint (p<0.001), with the mean weight gain in the risperidone group being 1.63 kg. Five patients in the risperidone group demonstrated ≥7% increase in body weight.

Since a switch to depression remains a concern for all treatments for bipolar mania, depressive symptoms were assessed with the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale throughout the trial. The overall decrease of Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores from baseline noted in the patients treated with risperidone suggests that risperidone would not be associated with a switch to depression.

Two factors support the robustness of risperidone’s treatment effect and make it unlikely that the use of lorazepam had bearing on the efficacy conclusions from this study. First, lorazepam was permitted during the first 10 days after randomization and was taken by more than 80% of the study population. Its use was very similar in both treatment groups. Second, there was a differential dropout early in the study (34.4% of placebo versus 22.4% of the risperidone patients had a treatment duration of 7 days or less).

A limitation of this study is the short duration. However, results of a 6-month open-label study with 430 bipolar disorder patients indicated that risperidone maintained highly significant improvements on the Young Mania Rating Scale, Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, CGI, and Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale subscales (p<0.0001)

(30). Over the course of this long-term trial, the percentage of patients treated with risperidone monotherapy (no mood stabilizers or antidepressants) ranged from 17% to 21%. Longer-term treatment with risperidone may be advantageous for a number of patients who are unable to tolerate the side effects associated with other agents currently used in the treatment of bipolar disorder.

In summary, this controlled trial demonstrated that risperidone monotherapy is efficacious and safe in the treatment of acute bipolar mania. Treatment with risperidone resulted in the rapid reduction of manic symptoms, as well as improvement across a broad range of symptoms and in psychosocial functioning. Additionally, risperidone produced significantly higher rates of remission than did placebo. These findings, along with the established benefit of risperidone in combination with a mood stabilizer, suggest that risperidone has an important role in the treatment of patients with bipolar mania.

Acknowledgments

The following investigators participated in the RIS-USA-239 trial: Americo Albala, M.D. (Chula Vista, Calif.); Mohammed Bari, M.D. (Chula Vista, Calif.); Jason Baron, M.D. (Houston, Tex.); Bijan Bastani, M.D. (Beachwood, Ohio); Louise Beckett, M.D. (Oklahoma City, Okla.); Ronald Brenner, M.D. (Lawrence, N.Y.); David Brown, M.D. (Austin, Tex.); Charles Charuvastra, M.D. (San Fernando, Calif.); Andrew Cutler, M.D. (Winter Park, Fla.); Bradley Diner, M.D. (Little Rock, Ark.); Louis Fabre, M.D., Ph.D. (Houston, Tex.); Thomas Gazda, M.D. (Phoenix, Ariz.); John Gilliam, M.D. (Richmond, Va.); John Grabowski, M.D. (New York, N.Y.); Scott Hoopes, M.D. (Boise, Idaho); Philip Janicak, M.D. (Chicago, Ill.); Arifulla Khan, M.D. (Bellevue, Wash.); Mary Ann Knesevich, M.D. (Dallas, Tex.); Michael Lambert, M.D. (Dallas, Tex.); Mark Lerman, M.D. (Hoffman Estates, Ill.); Robert Litman, M.D. (Rockville, Md.); Adam Lowy, M.D. (Washington, D.C.); Jerry Olsen, M.D. (San Antonio, Tex.); Kambiz Pahlavan, M.D. (West Allis, Wisc.); David Pickar, M.D. (Washington, D.C.); Michael Plopper, M.D. (San Diego, Calif.); Neil Richtand, M.D. (Cincinnati, Ohio); Robert Riesenberg, M.D. (Atlanta, Ga.); Murray Rosenthal, D.O. (San Diego, Calif.); David Sack, M.D. (Washington, D.C.); Wesley Smith, D.O. (Phoenix, Ariz.); Mark Townsend, M.D. (New Orleans, La.); Harold Udelman, M.D. (Phoenix, Ariz.); Richard Weisler, M.D. (Raleigh, N.C.).