A substantial literature documents the association between maternal major depression and dysfunction in offspring. Problems among offspring of depressed mothers have been found in areas ranging from mental and motor development in infancy to social competence and psychopathology in adolescence

(1). The disorders for which offspring of depressed mothers are at risk include two serious conditions—major depression and conduct disorder (e.g., reference

2)—that relate to problems in multiple domains of functioning (e.g., reference

3). Unfortunately, although assortative mating increases the likelihood that partners of depressed mothers will have some form of psychiatric disorder

(4), relatively little attention has been paid to the fathers of these children and their possible contribution to the likelihood of their offspring’s developing major depression and/or conduct disorder.

There is support for the idea that fathers may play a role in the association between maternal major depression and offspring dysfunction. However, the influence of paternal major depression in the association between maternal major depression and offspring major depression remains unclear. Foley et al.

(5) found that the risk of major depression in the offspring of depressed mothers was higher if the fathers were depressed as well, but Brennan et al.

(6) reported that maternal major depression was related to major depression in offspring only in families in which the fathers were

not depressed. Dierker et al.

(7) reported a direct relationship between the number of parents affected by certain disorders and risk for those disorders in offspring; in fact, risk for conduct disorder among offspring was elevated only if both parents were affected by a psychological disorder. Similarly, Merikangas et al.

(8) found higher rates of psychopathology among offspring of marital partners who were concordant for the presence of a psychiatric diagnosis, compared to couples in which only one partner had a psychiatric diagnosis. Conversely, the presence of a psychiatrically healthy father in the home was associated with lower rates of disorder among children of depressed mothers

(9). In addition, among children of depressed mothers, the fathers’ psychiatric status and the parents’ marital relationship explained much of the variability in children’s social and emotional competence

(10). In a study examining depressive symptoms, fathers’ scores on a measure of depression added to the prediction of emotional or behavioral problems in their children (as reported by teachers), beyond the variance accounted for by mothers’ depression scores

(11).

These findings about assortative mating and how it relates to offspring psychopathology led Connell and Goodman

(12) to recommend that researchers examine mental health in both spouses when studying links between parent and offspring psychopathology. Unfortunately, little is currently known about specific types of psychiatric illness among partners of depressed mothers; in addition, the potential association between different types of paternal psychopathology and risk to offspring is unclear. A clearer understanding of these relationships would clarify several important issues. First, knowledge of which psychiatric disorders tend to be present in partners of depressed women would aid our understanding both of people’s coupling practices and of the family makeup that children of depressed mothers experience. In addition, it could help clarify the reasons why children of depressed mothers are at risk for a diverse array of negative outcomes. As an extreme example, if all depressed women partnered with depressed men, then children of depressed mothers would, in actuality, be experiencing the effects of having two depressed parents. Eventually, a clearer understanding of these relationships could aid in the development of prevention and/or treatment programs for these youths. Studies that focus specifically on relationships between major depression and/or antisocial behavior among men who partner with depressed mothers likely would be particularly fruitful, since offspring of depressed mothers are at risk for both of these problems. Community-based studies would be especially valuable, since the findings would apply to the general population of depressed mothers and their children and would not be limited to those seeking treatment.

Thus, the first goal of this study was to examine whether, in a population-based sample, major depression and/or antisocial behavior tended to occur more frequently among the partners of depressed (versus nondepressed) mothers. Major depression was selected for investigation because of the possibility that depressed mothers engaged in “simple” assortative mating (mating with someone with their same disorder), combined with the fact that offspring of depressed mothers are at risk for major depression. Antisocial behavior was selected because offspring of depressed mothers are at risk for conduct disorder, and therefore it seemed particularly important to examine the potential presence of antisocial behavior among men who partner with depressed mothers

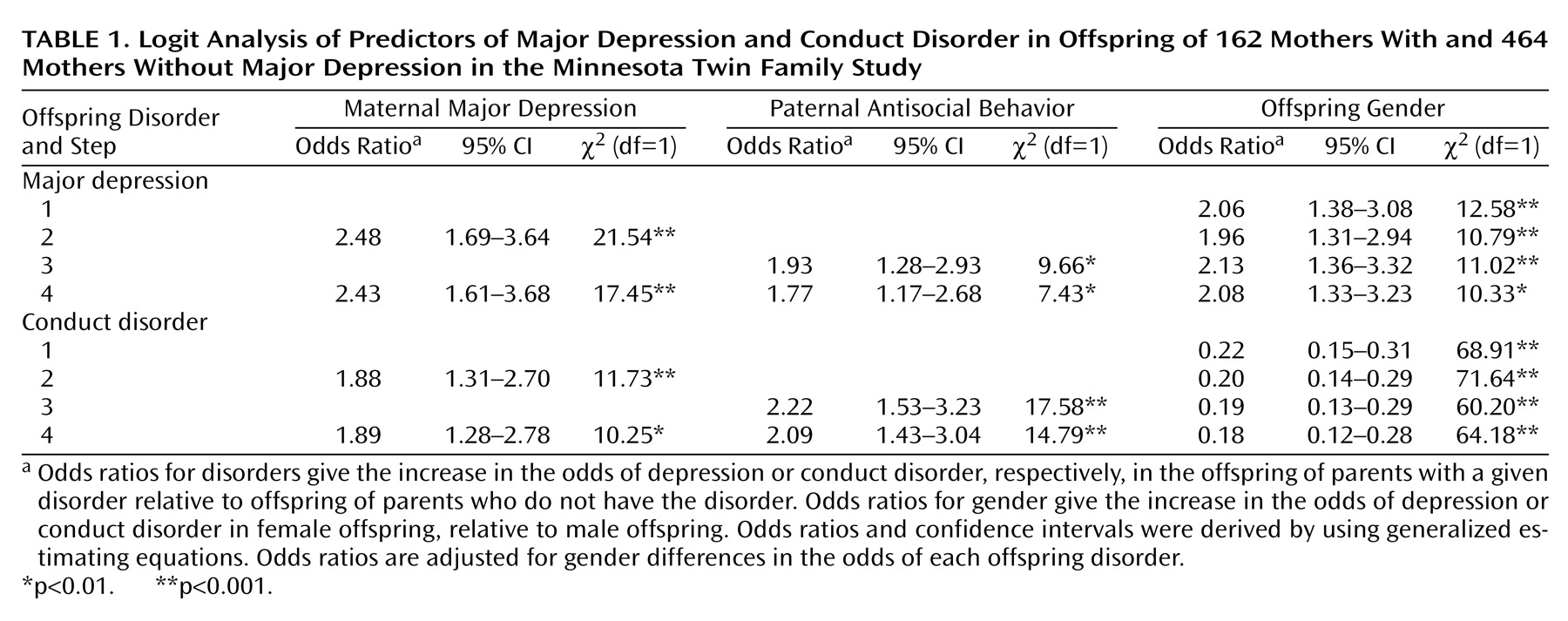

(4). It was expected that partners of depressed mothers would have higher than normal rates of both major depression and antisocial behavior (due to both assortative mating and the association between maternal major depression and offspring antisocial behavior). The second goal of this study was to examine how this/these paternal disorder(s) related to offspring psychopathology. It was expected that this/these associated paternal disorder(s) would mediate the relationship between maternal major depression and offspring psychopathology. Specifically, the relationship between maternal major depression and offspring major depression and conduct disorder was expected to be weaker when paternal disorder(s) associated with maternal major depression (selected based on the results of analyses addressing the first goal) were also taken into account. Gender was also considered as a potential moderating variable in these relationships. Although gender differences in the base rates of major depression and conduct disorder were expected, gender differences in the relationships between parental disorders and offspring major depression and conduct disorder were not expected.

Discussion

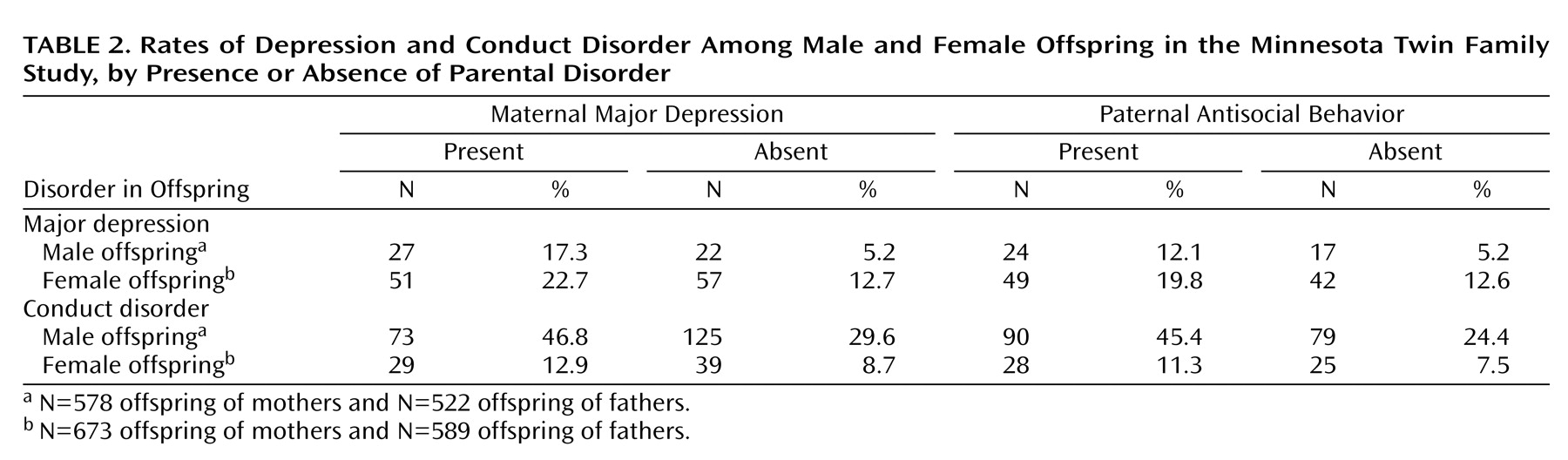

The results of this study indicated that maternal major depression and paternal antisocial behavior are both significantly and independently associated with both offspring major depression and offspring conduct disorder. No interaction of these parental disorders was found; the effect of one did not moderate the effect of the other. Thus, a youth with either a depressed mother or an antisocial father is at risk for both major depression and conduct disorder and also has an increased likelihood of having the other parent evidence these forms of psychopathology—resulting in risk from both parents. These results are thus consistent with other studies indicating that psychopathology in a child’s second parent increases risk among offspring

(4,

5,

7) and extend this line of study by showing in particular the importance of paternal antisocial behavior. In addition, major depression in mothers and antisocial behavior in fathers appear to be specifically related to major depression and conduct disorder in offspring—more so than antisocial behavior in mothers or major depression in fathers

(20). Thus, when fathers are not included in studies that examine offspring of depressed mothers, the results may be conflating the risk associated with having a depressed mother and the risk associated with having an antisocial father.

The mechanisms by which this risk to offspring is transmitted are not clear, but they likely include both genetic and environmental components. Both major depression and conduct disorder are influenced by genetic factors (e.g., references

21,

22). In addition, family risk factors (such as divorce, poor parental marital adjustment, and parent-child discord) are more common in families of depressed parents, compared to families in which the parents do not have major depression

(23). Parents with antisocial behavior are also more likely to divorce (or have children without being married) than parents without antisocial behavior

(24). Recent intergenerational research suggests that financial problems and parenting styles mediate the intergenerational continuity of antisocial behavior, with fathers’ adolescent delinquency and mothers’ parenting styles playing especially strong roles in predicting offspring antisocial behavior

(25). Chronic family stress and expressed emotion in fathers may mediate the relationship between parental psychopathology and offspring major depression

(6). Thus, it appears likely that both genetic and environmental factors, and quite possibly the interaction of these influences, affect the relationships found in this study between maternal major depression and offspring major depression and between paternal antisocial behavior and offspring conduct disorder. However, the potential reasons for the links between maternal major depression and offspring conduct disorder and between paternal antisocial behavior and offspring major depression are less clear. A more general genetic risk (not specific to a particular disorder, but relating to more general factors such as difficulties coping with stressful situations or social problems) may affect this type of transmission; in addition, the family risks that are common among families with a parent with major depression or antisocial behavior likely also act as risk factors for other disorders. These links may also be explained by more specific aspects of the parenting of mothers and fathers with these disorders; for example, mothers with major depression may be withdrawn and lethargic and therefore not monitor their children adequately, thereby placing them at risk for conduct disorder, while fathers with antisocial behavior may encounter trouble with the law, which could make their children upset or embarrassed, thereby placing them at risk for major depression.

The relationships found between parental and offspring disorders did not differ according to whether the offspring was male or female. Thus, the results of this study support the notion that associations between parental disorders and offspring disorders do not differ by gender, despite gender differences in the base rates of major depression and conduct disorder.

The results of this study also indicated that mothers with a history of major depression tend to partner with men who have a history of antisocial behavior. This association remains even when mothers who have a history of antisocial behavior in addition to their major depression are removed from the analysis, indicating that the pattern of depressed mothers’ partnering with antisocial fathers is not due to simple assortative mating for antisocial behavior. Conversely, no association was found between maternal major depression and paternal major depression, indicating that mothers with a history of major depression are no more likely to partner with depressed men than are their nondepressed counterparts.

The lack of an increased prevalence of major depression among partners of depressed mothers, compared to partners of nondepressed mothers, contradicts the findings of Brennan et al.

(6), who reported that spouses of depressed mothers were at increased risk for major depression. This difference may relate to the inclusion criteria for the two studies

(26). In the present study, all mothers with a history of probable or definite DSM-III-R major depression (based on a structured interview) for whom data were also available on biological fathers were included. In the Brennan et al. study, mothers first completed a self-report depression inventory and were considered for inclusion if they rated themselves as having moderate or severe depression at two or more time points (ranging from before the birth of the target child until the child was age 15 years), severe depression one time between the time they were pregnant and their child was age 5 years, or low-level depression at all time points. Then, they completed a structured interview assessing DSM-IV symptoms of major depressive disorder and dysthymic disorder. Because of these inclusion requirements, the participants in the study by Brennan et al. may have included primarily women with recurring depressive disorders—perhaps a more severely ill group than the women included in the present study. Brennan et al. specified that their study group was considered “high-risk,” while our sample was considered representative of the population.

It is not clear why this particular combination of parental disorders (depressed mothers and antisocial fathers) emerged as a common pattern. That is, one might expect to find simple assortative mating for antisocial behavior (as has been demonstrated by Krueger et al.

[19]) and major depression (as was found by Brennan et al.

[6]) separately. However, Dierker et al.

(7) did report differing concordance rates between spouses for different types of psychopathology; perhaps people with certain types of psychopathology tend to seek out people with psychological problems different from their own. Specifically, in this case, women who are depressed (and perhaps withdrawn or hopeless) may seek out men who appear strong and self-confident. Conversely, antisocial men may seek out women who are depressed and perhaps meek so that they can dominate and control them. It is important to remember, however, that this study measured lifetime diagnoses and therefore the temporal relationship among the disorders in mothers and fathers and the partnering of the two parents is unknown. Thus, it is possible that, for example, antisocial men partnered with women who were not initially depressed but that some women developed major depression as a result of distress over their partner’s antisocial behavior.

This study had several strengths. The selection of participants was community-based and therefore not biased toward people who sought treatment. We included families in which the biological parents had raised the children together until at least age 17 years as well as families in which the biological father had much less involvement with the children but still participated in the study. Thus, the results are not biased toward families that remained intact. In addition, through the use of statistical techniques that accommodated the fact that two offspring from each family were included, we were able to include diagnostic information on two offspring from each participating family. Although the inclusion of twins could be seen as reducing the generalizability of findings, previous research indicated that psychopathology among twins does not differ from psychopathology among nontwins

(27).

Several limitations of this study should also be noted. Participants were primarily Caucasian (99%), representing the demographic makeup of Minnesota at the time the twins were born. Participants were required to report on past behaviors; thus, as with all retrospective studies, these reports may have been subject to memory biases. In addition, somewhat fewer fathers in families with a depressed mother were full-time rearing fathers (compared to families with a nondepressed mother); it is possible that the results relating to offspring diagnoses would differ between families in which the biological father also reared the children and families in which the biological father was not a full-time rearing father. Thus, additional research addressing the relationships among parental psychopathology, family structure, and offspring psychopathology would be useful.