There are two known loci for medullary cystic kidney disease, a dominant condition leading to end-stage renal failure requiring transplantation in the third to fifth decade of life. Diagnosis is made from a combination of family history, polyuria with normal urinalysis, computerized tomography scan or ultrasound, and histological features, including tubular atrophy, interstitial fibrosis, and basement membrane thickening with material having a positive response to periodic acid–Schiff stain

(3,

4).

We have found no previous reports of bipolar disorder cosegregating with medullary cystic kidney disease.

Method

This family was identified as part of a multisite consortium project to collect families with bipolar disorder for linkage studies. The ascertainment and diagnostic methods have been described in detail elsewhere

(5). Written informed consent was obtained by using procedures approved by the University of California, San Diego, Human Research Protection Program. Following an interview with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)

(6), best-estimate consensus diagnoses were made by a panel of experienced clinicians who reviewed the SCID, medical records, and information from family informants when available. The diagnoses of medullary cystic kidney disease were made by the treating nephrologist, based on direct examination of the patient, family history, autopsy report, histology done on organs after transplant, sonogram, clinical history, and the presence of an elevated uric acid level.

Results

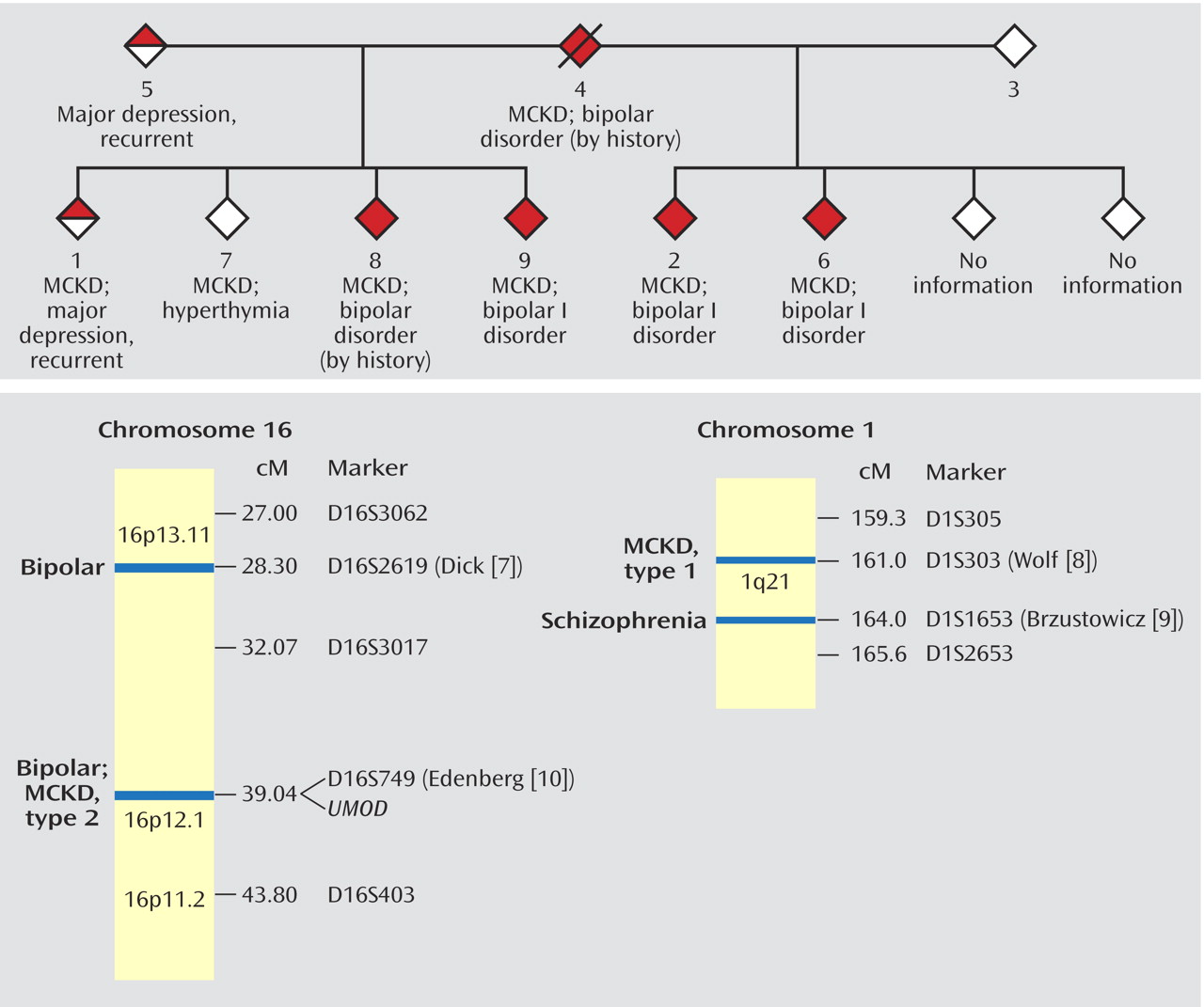

The family’s pedigree is illustrated in

Figure 1. No information was available on two siblings. All six half-siblings on whom information was available suffer from medullary cystic kidney disease. Members 1, 2, 6, and 7 had renal transplants between the ages of 24 and 37 years.

Members 2, 6, and 9 have bipolar I disorder according to the SCID interviews. Multiple family members, when questioned about members 4 and 8, were able to describe manic episodes meeting the DSM-IV criteria for duration, number of symptoms, and level of dysfunction. Member 1 received a diagnosis of major depressive disorder, recurrent. Member 7 reported a nonepisodic, lifelong history of high energy, successfully taking on multiple projects, and routinely needing only 4 hours of sleep per night. Member 7 met the criteria for hyperthymic temperament developed by Akiskal et al.

(11), which were assessed by using the TEMPS-A instrument, a self-rated version of the TEMPS-I.

Discussion

The age-corrected lifetime risk of bipolar disorder is 0.3%–1.5% in the general population. First-degree relatives of an individual with bipolar disorder are seven times as likely to be affected as are people in the general population

(12). Even with a bipolar parent, however, an individual with medullary cystic kidney disease in this family has a much higher risk of bipolar disorder than expected. Although four of the eight half-siblings may have a greater genetic loading because of a parent with depression, cosegregation is suggested in both sibships.

It is also possible that bipolar disorder is a result of medullary cystic kidney disease or its treatment. Although there are a few case reports of end-stage renal disease producing an organic mania syndrome

(13–

15) and transplant medications, such as glucocorticoids, have been associated with psychosis and depression, members of this pedigree met criteria for bipolar disorder before displaying evidence of medullary cystic kidney disease.

Cosegregation could be the result of the genes for medullary cystic kidney disease and bipolar disorder mapping close to each other on the same chromosome, with each gene carrying distinct point mutations. It is also possible that a mutation in one gene is responsible for both disorders. Finally, a chromosomal rearrangement, such as a deletion or inversion, could yield a breakpoint in genes for both disorders. Any of these possibilities could greatly facilitate the identification of a susceptibility gene for bipolar disorder.

Studies have narrowed the locus for type 1 medullary cystic kidney disease to a <650-kilobase (kb) interval centered on marker D1S303 on 1q21

(16–

18). Brzustowicz et al.

(9) reported a linkage 3 centimorgans (cM) away, between schizophrenia and marker D1S1653, with a maximum lod score of 6.50. Although members of the family reported here display bipolar disorder, and not schizophrenia, an overlap between the two disorders is seen in family studies and linkage analyses

(19,

20).

The disease-causing gene for the locus for type 2 medullary cystic kidney disease on 16p has been confirmed as

UMOD, which encodes the most common protein in urine, Tamm-Horsfall protein, or uromodulin

(21). Linkage of bipolar disorder to marker D16S749, only 500 kb away from

UMOD, was originally reported by Edenberg et al.

(10) and has been replicated in an expansion of that study group with a peak lod score of 2.8

(7).

This family is striking not only for the cosegregation of these two illnesses but also for the high rate of transmission. This could be consistent with an unbalanced translocation or other rearrangement such that transmission of the alternative chromosome does not result in viable offspring. An initial low-resolution cytogenetic analysis failed to identify any gross rearrangement in one of the members. Higher-resolution cytogenetic and molecular studies are indicated.

This family may be a valuable asset in the effort to map genes for both traits. It also suggests the value of screening families with medullary cystic kidney disease for mood disorders in order to identify similar families for mapping studies.