Patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) have high rates of suicidality

(1–

3), and comorbid PTSD increases suicidal behavior risk in depression

(4). There is also evidence of neuroendocrine alterations in PTSD

(5,

6), including elevations in the neuroactive steroid dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and its sulfated derivative

(7,

8). Neuroactive steroids rapidly alter neuronal excitability by acting at ligand-gated ion channel receptors in the cell membrane such as γ-aminobutyric acid type A (GABA

A) receptors

(9), among others. In addition to peripheral synthesis in the adrenals and gonads, many neuroactive steroids are synthesized de novo in the brain from cholesterol (neurosteroids). They are increased during the acute stress response

(10,

11) and may therefore modulate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal changes observed in PTSD. For example, the neuroactive steroid DHEA has antiglucocorticoid effects

(12,

13). It is also anxiolytic in rodent behavioral models

(14), but it negatively modulates GABA

A receptors

(15,

16). Since DHEA administration significantly elevates plasma levels of the neuroactive steroid allopregnanolone

(17), it is possible that DHEA-induced increases in this positive modulator of GABA

A receptors contribute to DHEA anxiolytic effects. These data suggest that neuroactive steroids may be relevant to the pathophysiology of PTSD and other anxiety disorders. Little is known regarding possible associations between neuroactive steroids and suicidal behaviors in PTSD. Therefore, we hypothesized that neuroactive steroid alterations may be related to suicidality in PTSD and investigated neuroactive steroid levels in male veterans with this disorder.

Method

We tested serum from 130 male veterans meeting DSM-IV criteria for PTSD who were enrolled in a larger multisite study of HIV seroprevalence and risks from the Durham Veterans Affairs inpatient psychiatric unit between March 1997 and June 2000. PTSD diagnosis was based on archival record review, in addition to the following criteria: an exacerbation of PTSD symptoms prompting the current psychiatric admission or military-service-connection status for PTSD at the time of admission. The PTSD Checklist was used for diagnostic confirmation (mean score=67, consistent with severe PTSD)

(18). Patients were evaluated with a validated structured risk interview composed of standardized measures that included the following domains: suicidal ideation or suicide attempt in the 6 months prior to admission, demographic information (age, ethnicity, marital status, educational level), smoking status and alcohol use disorders (Dartmouth Attitudes and Lifestyle Inventory Scale), and childhood sexual (Sexual Abuse Exposure Questionnaire) and physical (Conflict Tactics Scale) trauma

(19). All study participants provided written informed consent for the risk interview and serum sampling in the larger study. Samples were deidentified for the steroid assays, and the protocol was approved by the local institutional review board.

Serum was collected from each patient at 6:30 a.m. within 3 days of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. Radioimmunoassay analyses were performed (Diagnostic Products Corp., Los Angeles; ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Costa Mesa, Calif.) for a total of four steroids across a biosynthetic pathway: DHEA → androstenedione → testosterone (total) → estradiol. Intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were less than 9% for all four radioimmunoassays, and cross-reactivity with other steroids was minimal. Neuroactive steroid levels were obtained for most subjects; missing data secondary to limited serum volume were addressed by using case-wise deletion.

Wilcoxon rank sum statistics were used to examine bivariate associations between neuroactive steroids and suicidality. Bivariate associations between suicidality and smoking status, alcohol use disorder, and childhood trauma were examined by using Pearson chi-square statistics. Separate logistic regression models were examined for each neuroactive steroid, including age as a covariate (SAS version 8.2, SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

Results

A total of 130 male veterans with PTSD were evaluated; their mean age was 49.35 years (SD=8.13). This patient group was predominantly African American (N=62 [48%]) or Caucasian (N=63 [48%]), approximately one-third were married (N=48 [37%]), and more than half had been educated beyond high school (N=81 [62%]). Almost two-thirds (N=83 [64%]) had concurrent tobacco use, and 57 (44%) had alcohol use disorder. The majority had combat exposure (N=122 [94%]) and a history of childhood physical and/or sexual abuse (N=94 [72%]).

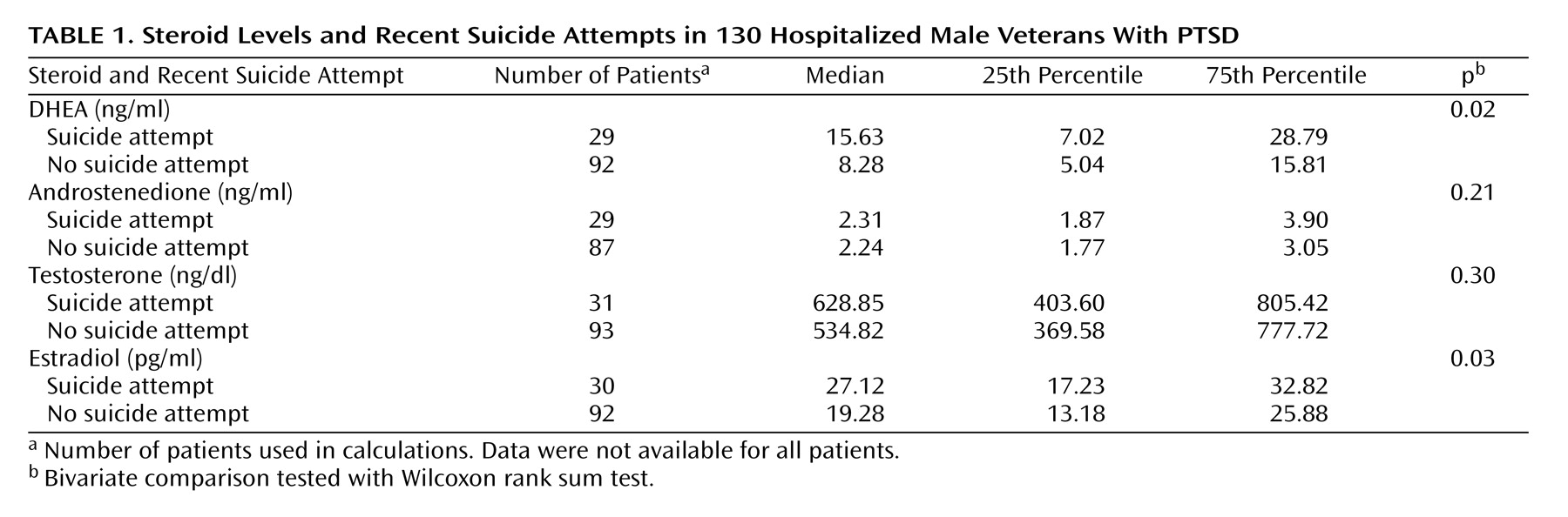

Our primary outcome variable was a suicide attempt in the last 6 months by patient self-report. One-quarter (N=33 [25%]) reported a suicide attempt and over two-thirds (N=90 [69%]) reported suicidal ideation. Patients who had attempted suicide demonstrated significantly higher median levels of DHEA and estradiol (

Table 1). No significant differences were observed in androstenedione or testosterone levels. Suicidal ideation was not statistically associated with neuroactive steroid levels in this sample.

Younger age was associated with attempted suicide (z=–2.43, p=0.02, two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test) and suicidal ideation (z=2.29, p=0.02, two-tailed Wilcoxon rank sum test). The median age of patients with recent suicide attempts was 49.7 years (interquartile range=6.3), compared with 50.7 years (interquartile range=4.1) for patients with no suicide attempts. DHEA levels remained associated with attempted suicide in the logistic regression analyses controlling for age (odds ratio=1.05 for each 1 ng/ml increase in DHEA level, 95% confidence interval=0.99–1.10, p<0.06). Higher estradiol levels were no longer associated with a greater risk of recent suicide attempt after adjustment for age (p=0.31). No other selected variables were associated with a history of suicide attempt, including concurrent alcohol use disorder (χ2=1.06, df=1, p=0.32), current tobacco use (χ2=0.66, df=1, p=0.53), or childhood trauma (χ2=0.004, df=1, p=1.00).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first report associating serum DHEA levels with suicide attempts in patients with PTSD. Since higher DHEA levels were correlated with a recent suicide attempt, this neuroactive steroid may be linked to the identification of suicide risk in patients with PTSD. Relevant to this finding, elevated DHEA levels have been reported in Israeli combat veterans with PTSD

(7), and higher levels of DHEA sulfate have been observed in resettled refugees with PTSD in Sweden

(8). Our findings of high suicidality rates in patients with PTSD are also consistent with the existing literature

(1–

3). In addition, a potential role for DHEA in depression has been suggested, although data are conflicting

(20). Since this study was designed to investigate behavioral risks in a large group of mentally ill veterans, we did not assess depressive symptoms specifically. Therefore, the relationship among depression, suicidality, and DHEA cannot be determined in this initial study.

The clinical relevance of DHEA elevations in PTSD patients with a recent suicide attempt is currently unclear. Since DHEA has antiglucocorticoid

(12,

13), neuroprotective

(21,

22), and neurotrophic

(23) effects, enhances learning and memory in animal models

(24), and also increases neurogenesis in rodents

(25) and human neural stem cell cultures

(26), it is tempting to speculate that DHEA elevations may be compensatory in nature. Alternatively, DHEA negative modulation of GABA

A receptors

(15,

16) could theoretically exacerbate anxiety symptoms. In addition, DHEA activity at

N-methyl-

d-aspartic acid

(23) and sigma-1

(27) receptors may also be relevant. Of note, a recent study

(28) demonstrated that the antipsychotic clozapine lowers cerebral cortical DHEA levels in rodents. Since clozapine treatment reduces suicide attempts in patients with schizophrenia

(29), it is possible that clozapine-induced decreases in DHEA (if these also occur in humans) may contribute to a reduction in suicidality following clozapine. The mechanisms mediating the association between higher DHEA levels and suicidality in PTSD will require further study.

Preliminary findings linking elevated DHEA levels in patients with PTSD to a suicide attempt in the past 6 months raises the possibility that DHEA is involved in PTSD pathophysiology. A relatively large number of subjects and a racially and ethnically diverse group are strengths of this study, but results should be interpreted with caution, given its cross-sectional design. Larger prospective efforts will be required to investigate this association more extensively.